Styracocephalus

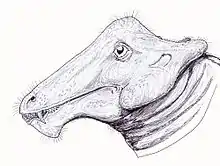

Styracocephalus platyrhynchus (Greek for “spiked-head”) is an extinct genus of dinocephalian therapsid that existed during the Mid-Permian throughout South Africa, but mainly in the Karoo Basin. It is often referred to by its single known species Styracocephalus platyrhynchus. The Dinocephalia clade consisted of the largest land vertebrates and herbivores during the early to mid-Permian. This period is often also referred to as the Guadalupian epoch, approximately 270 to 260 million years ago.[1][2]

| Styracocephalus Temporal range: Capitanian, | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Synapsida |

| Clade: | Therapsida |

| Suborder: | †Dinocephalia |

| Family: | †Styracocephalidae |

| Genus: | †Styracocephalus Haughton, 1929 |

| Species: | †S. platyrhynchus |

| Binomial name | |

| †Styracocephalus platyrhynchus Haughton, 1929 | |

Although multiple Styracocephalus skulls have been recovered, there has yet to be a specimen found of the entire therapsid skeleton. A majority of the skulls collected have also been mature skulls, as the juvenile tapinocephalid skulls are identified by having a small non-fused basioccipital.[3] The presence of enlarged canines, pachyostotic cranial boss, and horns are all plesiomorphic traits found in Dinocephalia.[4]Styracocephalus's head ornament meant that it could be recognised from a distance. One of the most striking feature of Styracocephalus is the large backward-protruding tabular horns.[5] It was around 1.8 metres (5 ft 11 in) in length,[6] with a 42-centimetre-long (17 in), 29-centimetre-wide (11 in) skull.[7]

History of Discovery

The first Styracocephalus fossil was discovered by Lieuwe Dirk Boonstra in 1928 from a Tapinocephalus bed on a farm called Boesmans Rivier, in the Beaufort West Division.[1] The original skeleton was crushed, but still showed some unique features such as outward projecting tabular horns, a shallow snout, and a small temporal opening. The skull had a maximum length of around 400 mm and a width of 390 mm.[8] Upon initial discovery, Boonstra compared the newfound specimen to Burnetia stating that the palate was more like that of a gorgonopsian than a therapsid. When Boonstra evaluated its place as a therapsid, it was found to contain characteristics resembling Therocephalia, Gorgonopsia, as well as Dinocephalia.[9] The first classification of Styracocephalus was in 1929 by S. H. Haughton and he placed it in its own new subclade of Therapsida due to its unique blend of features.[1] This original holotype that was found is called SAM 8936.[9]

Description

Skull

Although the SAM 8936 holotype was used to identify many characteristics of the skull, more recent specimens such as the SAM K 8071 specimen helped determine the posterior of the skull. The SAM K 8071 specimen was twice the size of the original holotype showing the variety seen in the morphological size of Styracocephalus.[9]

Styracocephalus has a narrow and long snout, with thickened postorbital bones. The median nasal boss is convex and is not connected to the extremely pachyostosed interorbital section. The cranial pachyostosis is split into four regions, the medial nasal boss, a think interorbital skull roof, paired posterior postorbital horns, and the squamosal boss that flares out laterally.[1] The frontal bone on the skull roof is not part of the dorsal rim of the orbit and instead extends anteriorly between the parietal and the nasal on the skull roof. The postfrontal is large and makes contact with both the frontal and the post-orbital. The tabular found on the dorsal lateral of the occiput of Styracocephalus is roughly rectangular and has been known to be variable in size. The postorbital includes a significant amount of the boss above the orbital, as well as the dorsal surface of the horn. It is in junction with the post-frontal, parietal, and squamosal. There are two parietals that form a pair on the midline in a triangular shape, also containing a small pineal foramen.[10] The occiput is rectangularly shaped and has thickened squamosal crests and these crests extend ventrally to the single temporal fenestrae. It also has a small temporal opening with the postorbital extending above it anteriorly.[9] A rather significant characteristic of the skull would be the tabular horns that extend laterally backward. The horn is one of the most distinguishable traits of Styracocephalus, and the name “spike-head” refers to these curved horns. The stapes in the skull are short with the distal end slightly swollen.[11] Most of the basicranial elements on known specimens of Strycacocephalus are poorly preserved, however, some portions such as the stapes are uniquely distinguishable and appear as small dumbbell-shaped bones that contact the fenestra and quadrate. When the skull is viewed posteriorly, it takes on a more square-like configuration.[9][1]

Dentition

Styracocephalus has large non-serrated canines which is not typical of tapinocephalids, except for Tapinocaninus and Ulemosaurus.[1][12] They also have heeled incisors and pronounced canines on the upper and lower jaw, however, Styracocephalus specifically has bulbous post-canines whereas other tapinocephalids often have leaf-shaped post-canines.[13]

There are typically around eight to ten of these post-canines that also have lingual heels. The incisors containing crushing heels are like those seen in Tapinocephalidae, Titanosuchidae, and Dinocephalia. The presence of lingual heels indicates the specimen is representative of Dinocephalia later in the mid-Permian. They also have crowns that are relatively blunt, which can be indicative of grinding plant material.[9]

Lower Jaw

The lower jaw of Styracocephalus has a large dentary that occupies almost three-fourths of the jaw when viewed laterally. The anterior margin of the jaw slopes posteroventral forming a slight chin on the anterior side of the lower jaw. The angular makes up a broad surface posterior to the dentary and forms a junction with the prearticular. The splenial is flat on the medial side of the jaw and resembles the shape of a spindle. The coronoid is elongated on the lower jaw immediately behind the canines, and also makes contact with the dentary. [1][14][9]

Palate

The palate of Styracocephalus is often well-preserved in many specimens. It has two paired pterygoids that make up a flat triangular surface that contacts and is concave to the dentary. The interpterygoidal vacuity is small and, on the midline, behind the transverse process. [9] There are small palatal teeth as well as paired vomers on the midline. Serrations, although not found on Styracocephalus, are found on Titanophoneus and Theriodontia. The palate also does not exhibit any suborbital fenestrae.[1]

Paleobiology

The Tapinocephalidae were one of the first earliest groups of herbivores as seen by their talon and heel-like dentition. The enamel on the heel of the dentition for many tapinocephalid specimens has signs of reduced deposition indicating the grinding action of consuming plant material.[15] Due to the smaller body size of Styracocephalus, it likely consumed smaller vegetative plants. Based on dinocephalian dentition, the presence of a large, heavy cranium and a poorly attached fragile mandible makes it difficult for this species to consume tough vegetation on dry ground. [16] One proposed purpose of horns on dinocephalians is to adapt to a less individualized behavioral pattern. With cranial ornaments especially, horns, that are often used for headbutting, this species demonstrates a more social and group-like behavior. [17]

Paleoecology

The majority of dinocephalian fossils such as that of Styracocephalus are found in the Tapinocephalus Assemblage Zone of the South African Karoo.[1] [16] Many of the more advanced tapinocephalid fossils, which exhibit characteristics seen in later mid-Permian Dinocephalia, are often found in this assemblage zone.[3]However recent recoveries of Mid-Permian Dinocephalia have been in South America, suggesting that they were dispersed in various locations across Pangea. This also supports that Therapsida were found on a global scale from as early as the Guadalupian including Eastern Europe and South America.[18] According to research conducted on the Karoo Basin in South Africa, Styracocephalus likely preferred warmer climate conditions with fluctuating precipitation. The basin was formed during Pangea time and survived through the breaking up of the continent, which likely contributes to the thorough global presence of Dinocephalia.[19] Many tapinocephalid fossils have also been discovered on farms such as the holotype found on the Boesmans Rivier farm, recent dinocephalian fossils have also been found on other farms like the Klein Wolwefontein. Consistent with assumptions made by Boonstra on characteristics of Dinocephalia, it can be inferred that Styracocephalus spent a fair amount of time in shallow ponds and marshlands. The ratio between the cranial elements and limbs of this group of Dinocephalia meant a decreased likelihood of long land travel, and a much higher probability of dwelling in marsh areas and eating nearby marsh vegetation.[20][16]

Classification

The Styracocephalus placement has long been questioned in the past due to debates regarding the familial classifications of Dinocephalia. It was previously thought that Styracocephalus made up its own dinocephalian family, as with Anterosauridae, Titanosuchidae, and Tapinocephalidae. The two reduced modern dinocephalian family subclade classifications are Anteosauria and Tapinocephalia, with Styracocephalidae and sister taxa Estemmenosuchidae classifying as tapinocephalids. Below is a cladogram depicting the relationship of the Styracocephalidae with other dinocephalians based on a phylogenetic study published in 2019. [1] [21]

| Therapsida |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- Fraser-King, Simon W.; Benoit, Julien; Day, Michael O.; Rubidge, Bruce S. (2019). "Cranial morphology and phylogenetic relationship of the enigmatic dinocephalian Styracocephalus platyrhynchus from the Karoo Supergroup, South Africa". Palaeontologia Africana. 54: 14–29.

- Megan. R. Whitney; Christian A. Sidor (2019). "Histological and developmental insights into the herbivorous dentition of tapinocephalid therapsids". PLOS ONE. 14 (10): e0223860. Bibcode:2019PLoSO..1423860W. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0223860. PMC 6821052. PMID 31665173.

- Modesto, S.P.; Rubidge, B.S.; de Klerk, W.J.; Welman, J. (2001). "A dinocephalian therapsid fauna on the Ecca-Beaufort contact in Eastern Cape Province, South Africa". South African Journal of Science. 97: 161–163.

- Megan. R. Whitney; Christian A. Sidor (2019). "Histological and developmental insights into the herbivorous dentition of tapinocephalid therapsids". PLOS ONE. 14 (10): e0223860. Bibcode:2019PLoSO..1423860W. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0223860. PMC 6821052. PMID 31665173.

- S. H. Haughton, 1929, "On some new therapsid genera", pg. 55

- "Torvosaurus - Facts and Pictures". 15 January 2016.

- S. H. Haughton, 1929, "On some new therapsid genera", pg. 55

- S. H. Haughton, 1929, "On some new therapsid genera", pg. 55

- Rubidge, B.S.; van den Heever, J.A. (1997). "Morphology and systematic position of the dinocephalian Styracocephalus platyrhynchus". Lethaia. 30 (2): 157–168. doi:10.1111/j.1502-3931.1997.tb00457.x.

- S. H. Haughton, 1929, "On some new therapsid genera", pg. 55

- S. H. Haughton, 1929, "On some new therapsid genera", pg. 55

- S. H. Haughton, 1929, "On some new therapsid genera", pg. 55

- Megan. R. Whitney; Christian A. Sidor (2019). "Histological and developmental insights into the herbivorous dentition of tapinocephalid therapsids". PLOS ONE. 14 (10): e0223860. Bibcode:2019PLoSO..1423860W. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0223860. PMC 6821052. PMID 31665173.

- S. H. Haughton, 1929, "On some new therapsid genera", pg. 55

- Megan. R. Whitney; Christian A. Sidor (2019). "Histological and developmental insights into the herbivorous dentition of tapinocephalid therapsids". PLOS ONE. 14 (10): e0223860. Bibcode:2019PLoSO..1423860W. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0223860. PMC 6821052. PMID 31665173.

- The skull of Tapinocephalus and its near relatives. Boonstra, LD. 1956. pp. 137–169.

- Megan. R. Whitney; Christian A. Sidor (2019). "Histological and developmental insights into the herbivorous dentition of tapinocephalid therapsids". PLOS ONE. 14 (10): e0223860. Bibcode:2019PLoSO..1423860W. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0223860. PMC 6821052. PMID 31665173.

- Schultz, Cesar L.; Şengör, A. M. Celâl; Rubidge, Bruce S.; Atayman-Güven, Saniye; Abdala, Fernando; Cisneros, Juan Carlos (2012-01-31). "Carnivorous dinocephalian from the Middle Permian of Brazil and tetrapod dispersal in Pangaea". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 109 (5): 1584–1588. Bibcode:2012PNAS..109.1584C. doi:10.1073/pnas.1115975109. ISSN 1091-6490. PMC 3277192. PMID 22307615.

- Catuneanu, O.; Wopfner, H.; Eriksson, P.G.; Cairncross, B.; Rubidge, B.S.; Smith, R.M.H.; Hancox, P.J. (2005). "The Karoo basins of south-central Africa". Journal of African Earth Sciences. 43 (1–3): 211–253. Bibcode:2005JAfES..43..211C. doi:10.1016/j.jafrearsci.2005.07.007.

- Boonstra, L.D., 1969. The fauna of the Tapinocephalus Zone (Beaufort beds of the Karoo)

- Boos, A. D. S.; Kammerer, C. F.; Schultz, C. L.; Paes Neto, V. D. (2015-11-01). "A tapinocephalid dinocephalian (Synapsida, Therapsida) from the Rio do Rasto Formation (Paraná Basin, Brazil): Taxonomic, ontogenetic and biostratigraphic considerations". Journal of South American Earth Sciences. 63: 375–384. Bibcode:2015JSAES..63..375B. doi:10.1016/j.jsames.2015.09.003. ISSN 0895-9811.

- The Origin and Evolution of Mammals (Oxford Biology) by T. S. Kemp

- Palaeos, Styracocephalus