Strontium

Strontium is the chemical element with the symbol Sr and atomic number 38. An alkaline earth metal, strontium is a soft silver-white yellowish metallic element that is highly chemically reactive. The metal forms a dark oxide layer when it is exposed to air. Strontium has physical and chemical properties similar to those of its two vertical neighbors in the periodic table, calcium and barium. It occurs naturally mainly in the minerals celestine and strontianite, and is mostly mined from these.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Strontium | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Appearance | silvery white metallic; with a pale yellow tint[1] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Standard atomic weight Ar°(Sr) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Strontium in the periodic table | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic number (Z) | 38 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Group | group 2 (alkaline earth metals) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Period | period 5 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Block | s-block | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electron configuration | [Kr] 5s2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrons per shell | 2, 8, 18, 8, 2[3] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Physical properties | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phase at STP | solid | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melting point | 1050 K (777 °C, 1431 °F) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boiling point | 1650 K (1377 °C, 2511 °F) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Density (near r.t.) | 2.64 g/cm3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| when liquid (at m.p.) | 2.375 g/cm3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of fusion | 7.43 kJ/mol | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of vaporization | 141 kJ/mol | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar heat capacity | 26.4 J/(mol·K) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Vapor pressure

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxidation states | +1,[4] +2 (a strongly basic oxide) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electronegativity | Pauling scale: 0.95 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ionization energies |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic radius | empirical: 215 pm | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Covalent radius | 195±10 pm | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Van der Waals radius | 249 pm | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other properties | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Natural occurrence | primordial | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

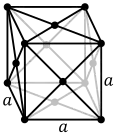

| Crystal structure | face-centered cubic (fcc) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal expansion | 22.5 µm/(m⋅K) (at 25 °C) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal conductivity | 35.4 W/(m⋅K) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrical resistivity | 132 nΩ⋅m (at 20 °C) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnetic ordering | paramagnetic | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar magnetic susceptibility | −92.0×10−6 cm3/mol (298 K)[5] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Young's modulus | 15.7 GPa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Shear modulus | 6.03 GPa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Poisson ratio | 0.28 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mohs hardness | 1.5 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CAS Number | 7440-24-6 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Naming | after the mineral strontianite, itself named after Strontian, Scotland | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Discovery | William Cruickshank (1787) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| First isolation | Humphry Davy (1808) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Isotopes of strontium | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Both strontium and strontianite are named after Strontian, a village in Scotland near which the mineral was discovered in 1790 by Adair Crawford and William Cruickshank; it was identified as a new element the next year from its crimson-red flame test color. Strontium was first isolated as a metal in 1808 by Humphry Davy using the then newly discovered process of electrolysis. During the 19th century, strontium was mostly used in the production of sugar from sugar beets (see strontian process). At the peak of production of television cathode-ray tubes, as much as 75% of strontium consumption in the United States was used for the faceplate glass.[7] With the replacement of cathode-ray tubes with other display methods, consumption of strontium has dramatically declined.[7]

While natural strontium (which is mostly the isotope strontium-88) is stable, the synthetic strontium-90 is radioactive and is one of the most dangerous components of nuclear fallout, as strontium is absorbed by the body in a similar manner to calcium. Natural stable strontium, on the other hand, is not hazardous to health.

Characteristics

Strontium is a divalent silvery metal with a pale yellow tint whose properties are mostly intermediate between and similar to those of its group neighbors calcium and barium.[8] It is softer than calcium and harder than barium. Its melting (777 °C) and boiling (1377 °C) points are lower than those of calcium (842 °C and 1484 °C respectively); barium continues this downward trend in the melting point (727 °C), but not in the boiling point (1900 °C). The density of strontium (2.64 g/cm3) is similarly intermediate between those of calcium (1.54 g/cm3) and barium (3.594 g/cm3).[9] Three allotropes of metallic strontium exist, with transition points at 235 and 540 °C.

The standard electrode potential for the Sr2+/Sr couple is −2.89 V, approximately midway between those of the Ca2+/Ca (−2.84 V) and Ba2+/Ba (−2.92 V) couples, and close to those of the neighboring alkali metals.[10] Strontium is intermediate between calcium and barium in its reactivity toward water, with which it reacts on contact to produce strontium hydroxide and hydrogen gas. Strontium metal burns in air to produce both strontium oxide and strontium nitride, but since it does not react with nitrogen below 380 °C, at room temperature it forms only the oxide spontaneously.[9] Besides the simple oxide SrO, the peroxide SrO2 can be made by direct oxidation of strontium metal under a high pressure of oxygen, and there is some evidence for a yellow superoxide Sr(O2)2.[11] Strontium hydroxide, Sr(OH)2, is a strong base, though it is not as strong as the hydroxides of barium or the alkali metals.[12] All four dihalides of strontium are known.[13]

Due to the large size of the heavy s-block elements, including strontium, a vast range of coordination numbers is known, from 2, 3, or 4 all the way to 22 or 24 in SrCd11 and SrZn13. The Sr2+ ion is quite large, so that high coordination numbers are the rule.[14] The large size of strontium and barium plays a significant part in stabilising strontium complexes with polydentate macrocyclic ligands such as crown ethers: for example, while 18-crown-6 forms relatively weak complexes with calcium and the alkali metals, its strontium and barium complexes are much stronger.[15]

Organostrontium compounds contain one or more strontium–carbon bonds. They have been reported as intermediates in Barbier-type reactions.[16][17][18] Although strontium is in the same group as magnesium, and organomagnesium compounds are very commonly used throughout chemistry, organostrontium compounds are not similarly widespread because they are more difficult to make and more reactive. Organostrontium compounds tend to be more similar to organoeuropium or organosamarium compounds due to the similar ionic radii of these elements (Sr2+ 118 pm; Eu2+ 117 pm; Sm2+ 122 pm). Most of these compounds can only be prepared at low temperatures; bulky ligands tend to favor stability. For example, strontium dicyclopentadienyl, Sr(C5H5)2, must be made by directly reacting strontium metal with mercurocene or cyclopentadiene itself; replacing the C5H5 ligand with the bulkier C5(CH3)5 ligand on the other hand increases the compound's solubility, volatility, and kinetic stability.[19]

Because of its extreme reactivity with oxygen and water, strontium occurs naturally only in compounds with other elements, such as in the minerals strontianite and celestine. It is kept under a liquid hydrocarbon such as mineral oil or kerosene to prevent oxidation; freshly exposed strontium metal rapidly turns a yellowish color with the formation of the oxide. Finely powdered strontium metal is pyrophoric, meaning that it will ignite spontaneously in air at room temperature. Volatile strontium salts impart a bright red color to flames, and these salts are used in pyrotechnics and in the production of flares.[9] Like calcium and barium, as well as the alkali metals and the divalent lanthanides europium and ytterbium, strontium metal dissolves directly in liquid ammonia to give a dark blue solution of solvated electrons.[8]

Isotopes

Natural strontium is a mixture of four stable isotopes: 84Sr, 86Sr, 87Sr, and 88Sr.[9] On these isotopes, 88Sr is the most abundant, makes up about 82.6% of all natural strontium, though the abundance varies due to the production of radiogenic 87Sr as the daughter of long-lived beta-decaying 87Rb.[20] This is the basis of rubidium–strontium dating. Of the unstable isotopes, the primary decay mode of the isotopes lighter than 85Sr is electron capture or positron emission to isotopes of rubidium, and that of the isotopes heavier than 88Sr is electron emission to isotopes of yttrium. Of special note are 89Sr and 90Sr. The former has a half-life of 50.6 days and is used to treat bone cancer due to strontium's chemical similarity and hence ability to replace calcium.[21][22] While 90Sr (half-life 28.90 years) has been used similarly, it is also an isotope of concern in fallout from nuclear weapons and nuclear accidents due to its production as a fission product. Its presence in bones can cause bone cancer, cancer of nearby tissues, and leukemia.[23] The 1986 Chernobyl nuclear accident contaminated about 30,000 km2 with greater than 10 kBq/m2 with 90Sr, which accounts for about 5% of the 90Sr which was in the reactor core.[24]

History

Strontium is named after the Scottish village of Strontian (Gaelic Sròn an t-Sìthein), where it was discovered in the ores of the lead mines.[25]

In 1790, Adair Crawford, a physician engaged in the preparation of barium, and his colleague William Cruickshank, recognised that the Strontian ores exhibited properties that differed from those in other "heavy spars" sources.[26] This allowed Crawford to conclude on page 355 "... it is probable indeed, that the scotch mineral is a new species of earth which has not hitherto been sufficiently examined." The physician and mineral collector Friedrich Gabriel Sulzer analysed together with Johann Friedrich Blumenbach the mineral from Strontian and named it strontianite. He also came to the conclusion that it was distinct from the witherite and contained a new earth (neue Grunderde).[27] In 1793 Thomas Charles Hope, a professor of chemistry at the University of Glasgow studied the mineral[28][29] and proposed the name strontites.[30][31][32] He confirmed the earlier work of Crawford and recounted: "... Considering it a peculiar earth I thought it necessary to give it an name. I have called it Strontites, from the place it was found; a mode of derivation in my opinion, fully as proper as any quality it may possess, which is the present fashion." The element was eventually isolated by Sir Humphry Davy in 1808 by the electrolysis of a mixture containing strontium chloride and mercuric oxide, and announced by him in a lecture to the Royal Society on 30 June 1808.[33] In keeping with the naming of the other alkaline earths, he changed the name to strontium.[34][35][36][37][38]

The first large-scale application of strontium was in the production of sugar from sugar beet. Although a crystallisation process using strontium hydroxide was patented by Augustin-Pierre Dubrunfaut in 1849[39] the large scale introduction came with the improvement of the process in the early 1870s. The German sugar industry used the process well into the 20th century. Before World War I the beet sugar industry used 100,000 to 150,000 tons of strontium hydroxide for this process per year.[40] The strontium hydroxide was recycled in the process, but the demand to substitute losses during production was high enough to create a significant demand initiating mining of strontianite in the Münsterland. The mining of strontianite in Germany ended when mining of the celestine deposits in Gloucestershire started.[41] These mines supplied most of the world strontium supply from 1884 to 1941. Although the celestine deposits in the Granada basin were known for some time the large scale mining did not start before the 1950s.[42]

During atmospheric nuclear weapons testing, it was observed that strontium-90 is one of the nuclear fission products with a relatively high yield. The similarity to calcium and the chance that the strontium-90 might become enriched in bones made research on the metabolism of strontium an important topic.[43][44]

Occurrence

Strontium commonly occurs in nature, being the 15th most abundant element on Earth (its heavier congener barium being the 14th), estimated to average approximately 360 parts per million in the Earth's crust[45] and is found chiefly as the sulfate mineral celestine (SrSO4) and the carbonate strontianite (SrCO3). Of the two, celestine occurs much more frequently in deposits of sufficient size for mining. Because strontium is used most often in the carbonate form, strontianite would be the more useful of the two common minerals, but few deposits have been discovered that are suitable for development.[46] Because of the way it reacts with air and water, strontium only exists in nature when combined to form minerals. Naturally occurring strontium is stable, but its synthetic isotope Sr-90 is only produced by nuclear fallout.

In groundwater strontium behaves chemically much like calcium. At intermediate to acidic pH Sr2+ is the dominant strontium species. In the presence of calcium ions, strontium commonly forms coprecipitates with calcium minerals such as calcite and anhydrite at an increased pH. At intermediate to acidic pH, dissolved strontium is bound to soil particles by cation exchange.[47]

The mean strontium content of ocean water is 8 mg/L.[48][49] At a concentration between 82 and 90 μmol/L of strontium, the concentration is considerably lower than the calcium concentration, which is normally between 9.6 and 11.6 mmol/L.[50][51] It is nevertheless much higher than that of barium, 13 μg/L.[9]

Production

The three major producers of strontium as celestine as of 2015 are China (150,000 t), Spain (90,000 t), and Mexico (70,000 t); Argentina (10,000 t) and Morocco (2,500 t) are smaller producers. Although strontium deposits occur widely in the United States, they have not been mined since 1959.[52]

A large proportion of mined celestine (SrSO4) is converted to the carbonate by two processes. Either the celestine is directly leached with sodium carbonate solution or the celestine is roasted with coal to form the sulfide. The second stage produces a dark-coloured material containing mostly strontium sulfide. This so-called "black ash" is dissolved in water and filtered. Strontium carbonate is precipitated from the strontium sulfide solution by introduction of carbon dioxide.[53] The sulfate is reduced to the sulfide by the carbothermic reduction:

- SrSO4 + 2 C → SrS + 2 CO2

About 300,000 tons are processed in this way annually.[54]

The metal is produced commercially by reducing strontium oxide with aluminium. The strontium is distilled from the mixture.[54] Strontium metal can also be prepared on a small scale by electrolysis of a solution of strontium chloride in molten potassium chloride:[10]

- Sr2+ + 2

e−

→ Sr - 2 Cl− → Cl2 + 2

e−

Applications

Consuming 75% of production, the primary use for strontium was in glass for colour television cathode-ray tubes,[54] where it prevented X-ray emission.[55][56] This application for strontium has been declining because CRTs are being replaced by other display methods. This decline has a significant influence on the mining and refining of strontium.[46] All parts of the CRT must absorb X-rays. In the neck and the funnel of the tube, lead glass is used for this purpose, but this type of glass shows a browning effect due to the interaction of the X-rays with the glass. Therefore, the front panel is made from a different glass mixture with strontium and barium to absorb the X-rays. The average values for the glass mixture determined for a recycling study in 2005 is 8.5% strontium oxide and 10% barium oxide.[57]

Because strontium is so similar to calcium, it is incorporated in the bone. All four stable isotopes are incorporated, in roughly the same proportions they are found in nature. However, the actual distribution of the isotopes tends to vary greatly from one geographical location to another. Thus, analyzing the bone of an individual can help determine the region it came from.[58][59] This approach helps to identify the ancient migration patterns and the origin of commingled human remains in battlefield burial sites.[60]

87Sr/86Sr ratios are commonly used to determine the likely provenance areas of sediment in natural systems, especially in marine and fluvial environments. Dasch (1969) showed that surface sediments of Atlantic displayed 87Sr/86Sr ratios that could be regarded as bulk averages of the 87Sr/86Sr ratios of geological terrains from adjacent landmasses.[61] A good example of a fluvial-marine system to which Sr isotope provenance studies have been successfully employed is the River Nile-Mediterranean system.[62] Due to the differing ages of the rocks that constitute the majority of the Blue and White Nile, catchment areas of the changing provenance of sediment reaching the River Nile Delta and East Mediterranean Sea can be discerned through strontium isotopic studies. Such changes are climatically controlled in the Late Quaternary.[62]

More recently, 87Sr/86Sr ratios have also been used to determine the source of ancient archaeological materials such as timbers and corn in Chaco Canyon, New Mexico.[63][64] 87Sr/86Sr ratios in teeth may also be used to track animal migrations.[65][66]

Strontium aluminate is frequently used in glow in the dark toys, as it is chemically and biologically inert.[67]

.jpg.webp)

Strontium carbonate and other strontium salts are added to fireworks to give a deep red colour.[68] This same effect identifies strontium cations in the flame test. Fireworks consume about 5% of the world's production.[54] Strontium carbonate is used in the manufacturing of hard ferrite magnets.[69][70]

Strontium chloride is sometimes used in toothpastes for sensitive teeth. One popular brand includes 10% total strontium chloride hexahydrate by weight.[71] Small amounts are used in the refining of zinc to remove small amounts of lead impurities.[9] The metal itself has a limited use as a getter, to remove unwanted gases in vacuums by reacting with them, although barium may also be used for this purpose.[10]

The ultra-narrow optical transition between the [Kr]5s2 1S0 electronic ground state and the metastable [Kr]5s5p 3P0 excited state of 87Sr is one of the leading candidates for the future re-definition of the second in terms of an optical transition as opposed to the current definition derived from a microwave transition between different hyperfine ground states of 133Cs.[72] Current optical atomic clocks operating on this transition already surpass the precision and accuracy of the current definition of the second.[73]

Radioactive strontium

89Sr is the active ingredient in Metastron,[74] a radiopharmaceutical used for bone pain secondary to metastatic bone cancer. The strontium is processed like calcium by the body, preferentially incorporating it into bone at sites of increased osteogenesis. This localization focuses the radiation exposure on the cancerous lesion.[22]

90Sr has been used as a power source for radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs). 90Sr produces approximately 0.93 watts of heat per gram (it is lower for the form of 90Sr used in RTGs, which is strontium fluoride).[75] However, 90Sr has one third the lifetime and a lower density than 238Pu, another RTG fuel. The main advantage of 90Sr is that it is cheaper than 238Pu and is found in nuclear waste. The Soviet Union deployed nearly 1000 of these RTGs on its northern coast as a power source for lighthouses and meteorology stations.[76][77]

Biological role

| Hazards | |

|---|---|

| GHS labelling: | |

| |

| Danger | |

| H261, H315 | |

| P223, P231+P232, P370+P378, P422[78] | |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

Acantharea, a relatively large group of marine radiolarian protozoa, produce intricate mineral skeletons composed of strontium sulfate.[79] In biological systems, calcium is substituted to a small extent by strontium.[80] In the human body, most of the absorbed strontium is deposited in the bones. The ratio of strontium to calcium in human bones is between 1:1000 and 1:2000, roughly in the same range as in the blood serum.[81]

Effect on the human body

The human body absorbs strontium as if it were its lighter congener calcium. Because the elements are chemically very similar, stable strontium isotopes do not pose a significant health threat. The average human has an intake of about two milligrams of strontium a day.[82] In adults, strontium consumed tends to attach only to the surface of bones, but in children, strontium can replace calcium in the mineral of the growing bones and thus lead to bone growth problems.[83]

The biological half-life of strontium in humans has variously been reported as from 14 to 600 days,[84][85] 1,000 days,[86] 18 years,[87] 30 years[88] and, at an upper limit, 49 years.[89] The wide-ranging published biological half-life figures are explained by strontium's complex metabolism within the body. However, by averaging all excretion paths, the overall biological half-life is estimated to be about 18 years.[90] The elimination rate of strontium is strongly affected by age and sex, due to differences in bone metabolism.[91]

The drug strontium ranelate aids bone growth, increases bone density, and lessens the incidence of vertebral, peripheral, and hip fractures.[92][93] However, strontium ranelate also increases the risk of venous thromboembolism, pulmonary embolism, and serious cardiovascular disorders, including myocardial infarction. Its use is therefore now restricted.[94] Its beneficial effects are also questionable, since the increased bone density is partially caused by the increased density of strontium over the calcium which it replaces. Strontium also bioaccumulates in the body.[95] Despite restrictions on strontium ranelate, strontium is still contained in some supplements.[96][97] There is not much scientific evidence on risks of strontium chloride when taken by mouth. Those with a personal or family history of blood clotting disorders are advised to avoid strontium.[96][97]

Strontium has been shown to inhibit sensory irritation when applied topically to the skin.[98][99] Topically applied, strontium has been shown to accelerate the recovery rate of the epidermal permeability barrier (skin barrier).[100]

Nuclear waste

Strontium-90 is a radioactive fission product produced by nuclear reactors used in nuclear power. It is a major component of high level radioactivity of nuclear waste and spent nuclear fuel. Its 29-year half life is short enough that its decay heat has been used to power arctic lighthouses, but long enough that it can take hundreds of years to decay to safe levels. Exposure from contaminated water and food may increase the risk of leukemia, bone cancer[101] and primary hyperparathyroidism.[102]

Remediation

Algae has shown selectivity for strontium in studies, where most plants used in bioremediation have not shown selectivity between calcium and strontium, often becoming saturated with calcium, which is greater in quantity and also present in nuclear waste.[101]

Researchers have looked at the bioaccumulation of strontium by Scenedesmus spinosus (algae) in simulated wastewater. The study claims a highly selective biosorption capacity for strontium of S. spinosus, suggesting that it may be appropriate for use in treating nuclear wastewater.[103]

A study of the pond alga Closterium moniliferum using non-radioactive strontium found that varying the ratio of barium to strontium in water improved strontium selectivity.[101]

See also

References

- Greenwood and Earnshaw, p. 112

- "Standard Atomic Weights: Strontium". CIAAW. 1969.

- "Periodic Table of Elements: Strontium - Sr (EnvironmentalChemistry.com)". environmentalchemistry.com. Retrieved 7 December 2022.

- Colarusso, P.; Guo, B.; Zhang, K.-Q.; Bernath, P. F. (1996). "High-Resolution Infrared Emission Spectrum of Strontium Monofluoride" (PDF). J. Molecular Spectroscopy. 175 (1): 158. Bibcode:1996JMoSp.175..158C. doi:10.1006/jmsp.1996.0019.

- Weast, Robert (1984). CRC, Handbook of Chemistry and Physics. Boca Raton, Florida: Chemical Rubber Company Publishing. pp. E110. ISBN 0-8493-0464-4.

- Kondev, F. G.; Wang, M.; Huang, W. J.; Naimi, S.; Audi, G. (2021). "The NUBASE2020 evaluation of nuclear properties" (PDF). Chinese Physics C. 45 (3): 030001. doi:10.1088/1674-1137/abddae.

- "Mineral Resource of the Month: Strontium". U.S. Geological Survey. 8 December 2014. Retrieved 16 August 2015.

- Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 112–13

- C. R. Hammond The elements (pp. 4–35) in Lide, D. R., ed. (2005). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (86th ed.). Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press. ISBN 0-8493-0486-5.

- Greenwood and Earnshaw, p. 111

- Greenwood and Earnshaw, p. 119

- Greenwood and Earnshaw, p. 121

- Greenwood and Earnshaw, p. 117

- Greenwood and Earnshaw, p. 115

- Greenwood and Earnshaw, p. 124

- Miyoshi, N.; Kamiura, K.; Oka, H.; Kita, A.; Kuwata, R.; Ikehara, D.; Wada, M. (2004). "The Barbier-Type Alkylation of Aldehydes with Alkyl Halides in the Presence of Metallic Strontium". Bulletin of the Chemical Society of Japan. 77 (2): 341. doi:10.1246/bcsj.77.341.

- Miyoshi, N.; Ikehara, D.; Kohno, T.; Matsui, A.; Wada, M. (2005). "The Chemistry of Alkylstrontium Halide Analogues: Barbier-type Alkylation of Imines with Alkyl Halides". Chemistry Letters. 34 (6): 760. doi:10.1246/cl.2005.760.

- Miyoshi, N.; Matsuo, T.; Wada, M. (2005). "The Chemistry of Alkylstrontium Halide Analogues, Part 2: Barbier-Type Dialkylation of Esters with Alkyl Halides". European Journal of Organic Chemistry. 2005 (20): 4253. doi:10.1002/ejoc.200500484.

- Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 136–37

- Greenwood and Earnshaw, p. 19

- Halperin, Edward C.; Perez, Carlos A.; Brady, Luther W. (2008). Perez and Brady's principles and practice of radiation oncology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 1997–. ISBN 978-0-7817-6369-1. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- Bauman, Glenn; Charette, Manya; Reid, Robert; Sathya, Jinka (2005). "Radiopharmaceuticals for the palliation of painful bone metastases – a systematic review". Radiotherapy and Oncology. 75 (3): 258.E1–258.E13. doi:10.1016/j.radonc.2005.03.003. PMID 16299924.

- "Strontium | Radiation Protection | US EPA". EPA. 24 April 2012. Retrieved 18 June 2012.

- "Chernobyl: Assessment of Radiological and Health Impact, 2002 update; Chapter I – The site and accident sequence" (PDF). OECD-NEA. 2002. Retrieved 3 June 2015.

- Murray, W. H. (1977). The Companion Guide to the West Highlands of Scotland. London: Collins. ISBN 978-0-00-211135-5.

- Crawford, Adair (1790). "On the medicinal properties of the muriated barytes". Medical Communications. 2: 301–59.

- Sulzer, Friedrich Gabriel; Blumenbach, Johann Friedrich (1791). "Über den Strontianit, ein Schottisches Foßil, das ebenfalls eine neue Grunderde zu enthalten scheint". Bergmännisches Journal: 433–36.

- "Thomas Charles Hope, MD, FRSE, FRS (1766-1844) - School of Chemistry". www.chem.ed.ac.uk.

- Doyle, W.P. "Thomas Charles Hope, MD, FRSE, FRS (1766–1844)". The University of Edinburgh. Archived from the original on 2 June 2013.

- Although Thomas C. Hope had investigated strontium ores since 1791, his research was published in: Hope, Thomas Charles (1798). "Account of a mineral from Strontian and of a particular species of earth which it contains". Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. 4 (2): 3–39. doi:10.1017/S0080456800030726. S2CID 251579302.

- Murray, T. (1993). "Elementary Scots: The Discovery of Strontium". Scottish Medical Journal. 38 (6): 188–89. doi:10.1177/003693309303800611. PMID 8146640. S2CID 20396691.

- Hope, Thomas Charles (1794). "Account of a mineral from Strontian and of a particular species of earth which it contains". Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. 3 (2): 141–49. doi:10.1017/S0080456800020275. S2CID 251579281.

- Davy, H. (1808). "Electro-chemical researches on the decomposition of the earths; with observations on the metals obtained from the alkaline earths, and on the amalgam procured from ammonia". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 98: 333–70. Bibcode:1808RSPT...98..333D. doi:10.1098/rstl.1808.0023. S2CID 96364168.

- Taylor, Stuart (19 June 2008). "Strontian gets set for anniversary". Lochaber News. Archived from the original on 13 January 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Weeks, Mary Elvira (1932). "The discovery of the elements: X. The alkaline earth metals and magnesium and cadmium". Journal of Chemical Education. 9 (6): 1046–57. Bibcode:1932JChEd...9.1046W. doi:10.1021/ed009p1046.

- Partington, J. R. (1942). "The early history of strontium". Annals of Science. 5 (2): 157. doi:10.1080/00033794200201411.

- Partington, J. R. (1951). "The early history of strontium. Part II". Annals of Science. 7: 95. doi:10.1080/00033795100202211.

- Many other early investigators examined strontium ore, among them: (1) Martin Heinrich Klaproth, "Chemische Versuche über die Strontianerde" (Chemical experiments on strontian ore), Crell's Annalen (September 1793) no. ii, pp. 189–202 ; and "Nachtrag zu den Versuchen über die Strontianerde" (Addition to the Experiments on Strontian Ore), Crell's Annalen (February 1794) no. i, p. 99 ; also (2) Kirwan, Richard (1794). "Experiments on a new earth found near Stronthian in Scotland". The Transactions of the Royal Irish Academy. 5: 243–56.

- Fachgruppe Geschichte Der Chemie, Gesellschaft Deutscher Chemiker (2005). Metalle in der Elektrochemie. pp. 158–62.

- Heriot, T. H. P (2008). "strontium saccharate process". Manufacture of Sugar from the Cane and Beet. Read Books. ISBN 978-1-4437-2504-0.

- Börnchen, Martin. "Der Strontianitbergbau im Münsterland". Archived from the original on 11 December 2014. Retrieved 9 November 2010.

- Martin, Josèm; Ortega-Huertas, Miguel; Torres-Ruiz, Jose (1984). "Genesis and evolution of strontium deposits of the granada basin (Southeastern Spain): Evidence of diagenetic replacement of a stromatolite belt". Sedimentary Geology. 39 (3–4): 281. Bibcode:1984SedG...39..281M. doi:10.1016/0037-0738(84)90055-1.

- "Chain Fission Yields". iaea.org.

- Nordin, B. E. (1968). "Strontium Comes of Age". British Medical Journal. 1 (5591): 566. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.5591.566. PMC 1985251.

- Turekian, K. K.; Wedepohl, K. H. (1961). "Distribution of the elements in some major units of the Earth's crust". Geological Society of America Bulletin. 72 (2): 175–92. Bibcode:1961GSAB...72..175T. doi:10.1130/0016-7606(1961)72[175:DOTEIS]2.0.CO;2.

- Ober, Joyce A. "Mineral Commodity Summaries 2010: Strontium" (PDF). United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 14 May 2010.

- Heuel-Fabianek, B. (2014). "Partition Coefficients (Kd) for the Modelling of Transport Processes of Radionuclides in Groundwater" (PDF). Berichte des Forschungszentrums Jülich. 4375. ISSN 0944-2952.

- Stringfield, V. T. (1966). "Strontium". Artesian water in Tertiary limestone in the southeastern States. Geological Survey Professional Paper. United States Government Printing Office. pp. 138–39.

- Angino, Ernest E.; Billings, Gale K.; Andersen, Neil (1966). "Observed variations in the strontium concentration of sea water". Chemical Geology. 1: 145. Bibcode:1966ChGeo...1..145A. doi:10.1016/0009-2541(66)90013-1.

- Sun, Y.; Sun, M.; Lee, T.; Nie, B. (2005). "Influence of seawater Sr content on coral Sr/Ca and Sr thermometry". Coral Reefs. 24: 23. doi:10.1007/s00338-004-0467-x. S2CID 31543482.

- Kogel, Jessica Elzea; Trivedi, Nikhil C.; Barker, James M. (5 March 2006). Industrial Minerals & Rocks: Commodities, Markets, and Uses. ISBN 978-0-87335-233-8.

- Ober, Joyce A. "Mineral Commodity Summaries 2015: Strontium" (PDF). United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

- Kemal, Mevlüt; Arslan, V.; Akar, A.; Canbazoglu, M. (1996). Production of SrCO3 by black ash process: Determination of reductive roasting parameters. CRC Press. p. 401. ISBN 978-90-5410-829-0.

- MacMillan, J. Paul; Park, Jai Won; Gerstenberg, Rolf; Wagner, Heinz; Köhler, Karl and Wallbrecht, Peter (2002) "Strontium and Strontium Compounds" in Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. doi:10.1002/14356007.a25_321.

- "Cathode Ray Tube Glass-To-Glass Recycling" (PDF). ICF Incorporated, USEP Agency. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 December 2008. Retrieved 7 January 2012.

- Ober, Joyce A.; Polyak, Désirée E. "Mineral Yearbook 2007: Strontium" (PDF). United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 14 October 2008.

- Méar, F.; Yot, P.; Cambon, M.; Ribes, M. (2006). "The characterization of waste cathode-ray tube glass". Waste Management. 26 (12): 1468–76. Bibcode:2006WaMan..26.1468M. doi:10.1016/j.wasman.2005.11.017. PMID 16427267.

- Price, T. Douglas; Schoeninger, Margaret J.; Armelagos, George J. (1985). "Bone chemistry and past behavior: an overview". Journal of Human Evolution. 14 (5): 419–47. doi:10.1016/S0047-2484(85)80022-1.

- Steadman, Luville T.; Brudevold, Finn; Smith, Frank A. (1958). "Distribution of strontium in teeth from different geographic areas". The Journal of the American Dental Association. 57 (3): 340–44. doi:10.14219/jada.archive.1958.0161. PMID 13575071.

- Schweissing, Matthew Mike; Grupe, Gisela (2003). "Stable strontium isotopes in human teeth and bone: a key to migration events of the late Roman period in Bavaria". Journal of Archaeological Science. 30 (11): 1373–83. Bibcode:2003JArSc..30.1373S. doi:10.1016/S0305-4403(03)00025-6.

- Dasch, J. (1969). "Strontium isotopes in weathering profiles, deep-sea sediments, and sedimentary rocks". Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. 33 (12): 1521–52. Bibcode:1969GeCoA..33.1521D. doi:10.1016/0016-7037(69)90153-7.

- Krom, M. D.; Cliff, R.; Eijsink, L. M.; Herut, B.; Chester, R. (1999). "The characterisation of Saharan dusts and Nile particulate matter in surface sediments from the Levantine basin using Sr isotopes". Marine Geology. 155 (3–4): 319–30. Bibcode:1999MGeol.155..319K. doi:10.1016/S0025-3227(98)00130-3.

- Benson, L.; Cordell, L.; Vincent, K.; Taylor, H.; Stein, J.; Farmer, G. & Kiyoto, F. (2003). "Ancient maize from Chacoan great houses: where was it grown?". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 100 (22): 13111–15. Bibcode:2003PNAS..10013111B. doi:10.1073/pnas.2135068100. PMC 240753. PMID 14563925.

- English NB; Betancourt JL; Dean JS; Quade J. (October 2001). "Strontium isotopes reveal distant sources of architectural timber in Chaco Canyon, New Mexico". Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 98 (21): 11891–96. Bibcode:2001PNAS...9811891E. doi:10.1073/pnas.211305498. PMC 59738. PMID 11572943.

- Barnett-Johnson, Rachel; Grimes, Churchill B.; Royer, Chantell F.; Donohoe, Christopher J. (2007). "Identifying the contribution of wild and hatchery Chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) to the ocean fishery using otolith microstructure as natural tags". Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences. 64 (12): 1683–92. doi:10.1139/F07-129. S2CID 54885632.

- Porder, S.; Paytan, A. & E.A. Hadly (2003). "Mapping the origin of faunal assemblages using strontium isotopes". Paleobiology. 29 (2): 197–204. doi:10.1666/0094-8373(2003)029<0197:MTOOFA>2.0.CO;2. S2CID 44206756.

- Van der Heggen, David (October 2022). "Persistent Luminescence in Strontium Aluminate: A Roadmap to a Brighter Future". Advanced Functional Materials. 32 (52). doi:10.1002/adfm.202208809. hdl:1854/LU-01GJ1338HX6QQBT438E4QW442N. S2CID 253347258. Retrieved 21 April 2023.

- "Chemistry of Firework Colors – How Fireworks Are Colored". Chemistry.about.com. 10 April 2012. Archived from the original on 13 May 2008. Retrieved 14 April 2012.

- "Ferrite Permanent Magnets". Arnold Magnetic Technologies. Archived from the original on 14 May 2012. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- "Barium Carbonate". Chemical Products Corporation. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- Ghom (1 December 2005). Textbook of Oral Medicine. Jaypee Brothers, Medical Publishers. p. 885. ISBN 978-81-8061-431-6.

- Cartlidge, Edwin (28 February 2018). "With better atomic clocks, scientists prepare to redefine the second". Science | AAAS. Retrieved 10 February 2019.

- "Recommended values of standard frequencies - BIPM". www.bipm.org. Retrieved 21 May 2023.

- "FDA ANDA Generic Drug Approvals". Food and Drug Administration.

- "What are the fuels for radioisotope thermoelectric generators?". qrg.northwestern.edu.

- Doyle, James (30 June 2008). Nuclear safeguards, security and nonproliferation: achieving security with technology and policy. Elsevier. p. 459. ISBN 978-0-7506-8673-0.

- O'Brien, R. C.; Ambrosi, R. M.; Bannister, N. P.; Howe, S. D.; Atkinson, H. V. (2008). "Safe radioisotope thermoelectric generators and heat sources for space applications". Journal of Nuclear Materials. 377 (3): 506–21. Bibcode:2008JNuM..377..506O. doi:10.1016/j.jnucmat.2008.04.009.

- "Strontium 343730". Sigma-Aldrich.

- De Deckker, Patrick (2004). "On the celestite-secreting Acantharia and their effect on seawater strontium to calcium ratios". Hydrobiologia. 517 (1–3): 1. doi:10.1023/B:HYDR.0000027333.02017.50. S2CID 42526332.

- Pors Nielsen, S. (2004). "The biological role of strontium". Bone. 35 (3): 583–88. doi:10.1016/j.bone.2004.04.026. PMID 15336592.

- Cabrera, Walter E.; Schrooten, Iris; De Broe, Marc E.; d'Haese, Patrick C. (1999). "Strontium and Bone". Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 14 (5): 661–68. doi:10.1359/jbmr.1999.14.5.661. PMID 10320513. S2CID 32627349.

- Emsley, John (2011). Nature's building blocks: an A–Z guide to the elements. Oxford University Press. p. 507. ISBN 978-0-19-960563-7.

- Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (21 January 2015). "ATSDR – Public Health Statement: Strontium". cdc.gov. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- Tiller, B. L. (2001), "4.5 Fish and Wildlife Surveillance" (PDF), Hanford Site 2001 Environmental Report, DOE, archived from the original (PDF) on 11 May 2013, retrieved 14 January 2014

- Driver, C. J. (1994), Ecotoxicity Literature Review of Selected Hanford Site Contaminants (PDF), DOE, doi:10.2172/10136486, OSTI 10136486, retrieved 14 January 2014

- "Freshwater Ecology and Human Influence". Area IV Envirothon. Archived from the original on 1 January 2014. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- "Radioisotopes That May Impact Food Resources" (PDF). Epidemiology, Health and Social Services, State of Alaska. Archived from the original on 21 August 2014. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - "Human Health Fact Sheet: Strontium" (PDF). Argonne National Laboratory. October 2001. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 January 2014. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- "Biological Half-life". HyperPhysics. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- Glasstone, Samuel; Dolan, Philip J. (1977). "XII: Biological Effects" (PDF). The effects of Nuclear Weapons. p. 605. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- Shagina, N. B.; Bougrov, N. G.; Degteva, M. O.; Kozheurov, V. P.; Tolstykh, E. I. (2006). "An application of in vivo whole body counting technique for studying strontium metabolism and internal dose reconstruction for the Techa River population". Journal of Physics: Conference Series. 41 (1): 433–40. Bibcode:2006JPhCS..41..433S. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/41/1/048. S2CID 32732782.

- Meunier P. J.; Roux C.; Seeman E.; Ortolani, S.; Badurski, J. E.; Spector, T. D.; Cannata, J.; Balogh, A.; Lemmel, E. M.; Pors-Nielsen, S.; Rizzoli, R.; Genant, H. K.; Reginster, J. Y. (January 2004). "The effects of strontium ranelate on the risk of vertebral fracture in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis" (PDF). New England Journal of Medicine. 350 (5): 459–68. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa022436. hdl:2268/7937. PMID 14749454.

- Reginster JY; Seeman E; De Vernejoul MC; Adami, S.; Compston, J.; Phenekos, C.; Devogelaer, J. P.; Diaz Curiel, M.; Sawicki, A.; Goemaere, S.; Sorensen, O. H.; Felsenberg, D.; Meunier, P. J. (May 2005). "Strontium ranelate reduces the risk of nonvertebral fractures in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis: treatment of peripheral osteoporosis (TROPOS) study" (PDF). The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 90 (5): 2816–22. doi:10.1210/jc.2004-1774. PMID 15728210.

- "Strontium ranelate: cardiovascular risk – restricted indication and new monitoring requirements". Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency, UK. March 2014.

- Price, Charles T.; Langford, Joshua R.; Liporace, Frank A. (5 April 2012). "Essential Nutrients for Bone Health and a Review of their Availability in the Average North American Diet". Open Orthop. J. 6: 143–49. doi:10.2174/1874325001206010143. PMC 3330619. PMID 22523525.

- "Strontium". WebMD. Retrieved 20 November 2017.

- "Strontium for Osteoporosis". WebMD. Retrieved 20 November 2017.

- Hahn, G.S. (1999). "Strontium Is a Potent and Selective Inhibitor of Sensory Irritation" (PDF). Dermatologic Surgery. 25 (9): 689–94. doi:10.1046/j.1524-4725.1999.99099.x. PMID 10491058. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 May 2016.

- Hahn, G.S. (2001). Anti-irritants for Sensory Irritation. p. 285. ISBN 978-0-8247-0292-2.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - Kim, Hyun Jeong; Kim, Min Jung; Jeong, Se Kyoo (2006). "The Effects of Strontium Ions on Epidermal Permeability Barrier". The Korean Dermatological Association, Korean Journal of Dermatology. 44 (11): 1309. Archived from the original on 4 June 2021. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- Potera, Carol (2011). "HAZARDOUS WASTE: Pond Algae Sequester Strontium-90". Environ Health Perspect. 119 (6): A244. doi:10.1289/ehp.119-a244. PMC 3114833. PMID 21628117.

- Boehm, BO; Rosinger, S; Belyi, D; Dietrich, JW (18 August 2011). "The parathyroid as a target for radiation damage". The New England Journal of Medicine. 365 (7): 676–8. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1104982. PMID 21848480.

- Liu, Mingxue; Dong, Faqin; Kang, Wu; Sun, Shiyong; Wei, Hongfu; Zhang, Wei; Nie, Xiaoqin; Guo, Yuting; Huang, Ting; Liu, Yuanyuan (2014). "Biosorption of Strontium from Simulated Nuclear Wastewater by Scenedesmus spinosus under Culture Conditions: Adsorption and Bioaccumulation Processes and Models". Int J Environ Res Public Health. 11 (6): 6099–6118. doi:10.3390/ijerph110606099. PMC 4078568. PMID 24919131.

Bibliography

- Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

External links

- WebElements.com – Strontium

- Strontium at The Periodic Table of Videos (University of Nottingham)