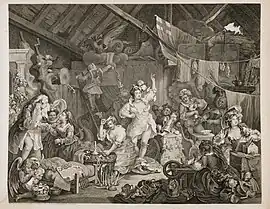

Strolling Actresses Dressing in a Barn

Strolling Actresses Dressing in a Barn is a painting from 1738 by British artist William Hogarth. It was reproduced as an engraving and issued with Four Times of the Day as a five print set in the same year. The painting depicts a company of actresses preparing for their final performance before the troupe is disbanded as a result of the Licensing Act 1737. Brought in as a result of John Gay's Beggar's Opera of 1728, which had linked Robert Walpole with the notorious criminal Jonathan Wild, the Licensing Act made it compulsory for new plays to be approved by the Lord Chamberlain, and, more importantly for the characters depicted, closed any non-patent theatres. The majority of the painting was completed before the Act was passed in 1737, but its passing into law was no surprise and it was the work of a moment for Hogarth to insert a reference to the Act itself into the picture.

| Strolling Actresses Dressing in a Barn | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | William Hogarth |

| Year | 1738 |

While not part of the Four Times of the Day series, it appears that it was Hogarth's intention from the outset to sell the five prints together, Strolling Actresses complemented Four Times just as Southwark Fair had done with A Rake's Progress. Whereas the characters in Four Times play their roles without being conscious of acting, the company in this picture are fully aware of the differences between the reality of their lives and the roles they are set to play. Some of the goddesses portrayed by the inhabitants of the scenes in Four Times of the Day are reproduced here as characters in the forthcoming play.

The troupe are preparing for the play The Devil to Pay in Heaven, a fiction that was probably intended as a satire on the mystery plays which were heavily controlled by the church. Hogarth contrasts the roles of gods and goddesses that appear in the play with the mortal reality at every turn. The leaky, draughty barn stands in for the heavens in which they will shortly be play acting. The playbill on the bed introduces the cast and aids the viewer in identifying the figures portrayed: Diana, Flora, Juno, Night, Siren, Aurora, Eagle, Cupid, two Devils, a Ghost and attendants.

Like other Hogarth prints, such as Southwark Fair and The Enraged Musician, a pretty woman takes centre stage – in this case, Diana, identifiable by her crescent moon headdress, practising her pose. She imitates the Diana of Versailles, but she looks foolish as she has neither quiver nor arrows. Her hooped petticoat has fallen to her feet, exposing her thighs, and the low neckline of her shirt reveals her breasts; she is anything but the chaste goddess. She acknowledges the attention of the viewer with a slight smile. To her left Flora is dusting her hair with a flour-shaker in front of a broken mirror propped up by a candle, in an effort to prepare herself for the role of the fertility goddess. Cupid "floats" above them with the aid of a ladder, fetching two stockings for Apollo, identifiable from the sun on his head, who points out with the aid of a bow their hanging place on a cloud beneath a dragon. Next to the actress playing Diana, two children dressed as devils help themselves to a mug of beer left on the altar like a sacrifice. A woman next to them (possibly their mother) is shocked by their behaviour but she has her hands full assisting the "ghost" to bleed a cat from its tail. As with many of Hogarth's cats, this one is reaping the rewards of life as an outsider. An old wives' tale of the time claimed that to recover from a bad fall you should suck the blood from the freshly amputated tail of a tom cat. Here the cat has a role forced upon it in the same way that actresses fill inappropriate roles.

Above the women in this corner, a face peers down through the opening in the barn roof. Here a low mortal looks down on the gods from heaven, rather than the other way round. He fills the role of Actaeon, who accidentally saw Diana naked and was changed into a stag and torn apart by his own hounds as punishment. Here though the viewing of Diana is intentional. In the right foreground, Juno practices her lines, while Night, identifiable by her star-spangled headdress, darns a hole in her stocking.

In front of Night and Juno is Hogarth's take on a vanitas, but here the symbols of death are replaced by comic figures: a monkey wearing a cloak urinates into a helmet; one kitten plays with an orb while another plays with a harp; bags and coffee pots litter the table. The monkey and kittens presumably fill the roles of attendants mentioned in the playbill; their play acting as a human serves to highlight further the difference between acting and reality.

To the left of the picture, Ganymede, who is not yet fully dressed, accepts a drink of gin to ease the pain of his toothache from the Siren, who is being attended by Aurora, identified by the morning star on her headdress. In the foreground a woman costumed as Jove's eagle feeds her child; the food rests on a crown with a small folded paper bearing the title The Act against Strolling Players. Next to her, Ganymede's breeches lie on the small bed adjacent to the playbill, which is slipping perilously close to the chamberpot.

Horace Walpole (the son of Robert Walpole, the First Lord of the Treasury, who had pushed through the Licensing Act) rated Strolling Actresses as Hogarth's greatest work "for wit and imagination, without any other end", but Charles Lamb found the characters lacking in expressiveness, while acknowledging the depiction of their activity and camaraderie.

The engraving was first published on 25 March 1738, along with Four Times of the Day. The painting was sold at auction along with the original paintings for A Harlot's Progress, A Rake's Progress and Four Times of the Day in January 1745, but was destroyed in a fire at Littleton House near Staines in 1874.

See also

References

- I. R. F. Gordon (5 November 2003). "The Four Times of the Day and Strolling Actresses Dressing in a Barn". The Literary Encyclopedia. Retrieved 6 June 2007.

- Hogarth, William (1833). "Remarks on various prints". Anecdotes of William Hogarth, Written by Himself: With Essays on His Life and Genius, and Criticisms on his Work. J.B. Nichols and Son. p. 416.

- Paulson, Ronald (1992). Hogarth: High Art and Low, 1732–50 Vol 2. Lutterworth Press. p. 508. ISBN 0718828550.

- Paulson, Ronald (2003). Hogarth's "Harlot": Sacred Parody in Enlightenment England. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 424. ISBN 0801873916.

- Champlin, John Denison; Perkins, Charles Callahan (1927). Cyclopedia of Painters and Paintings. Empire State Book Co.

- Mark Hallett and Christine Riding (2006). Hogarth. Tate Publishing, p. 136. ISBN 1-85437-662-4.