Strava

Strava ("to strive" in Swedish) is an American internet service for tracking physical exercise which incorporates social network features. It started out tracking mostly outdoor cycling and running activities using Global Positioning System data, but now incorporates several dozen other exercise types, including indoor activities.[4] Strava uses a freemium model with some features only available in the paid subscription plan. The service was founded in 2009 by Mark Gainey and Michael Horvath and is based in San Francisco, California.

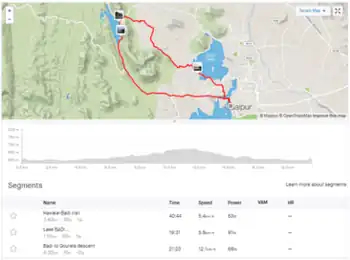

An activity shown on the Strava website | |

| Developer(s) | Strava, Inc |

|---|---|

| Initial release | 2009 |

| Stable release | |

| Operating system | Android, iOS 13 or later, Web browser |

| Size | 138.8 MB (iOS); 44.85 MB (Android) |

| Available in | 14 languages[3][2] |

List of languages English, Dutch, French, German, Italian, Japanese, Korean, Portuguese(Portugal), Portuguese(Brazil), Russian, Simplified Chinese, Spanish(Spain), Spanish(Latin America) and Traditional Chinese | |

| Type | Fitness |

| License | Proprietary |

| Website | strava |

Overview

Strava records data for a user's activities, which can then be shared with the user's followers or shared publicly. If an activity is shared publicly, Strava automatically groups activities that occur at the same time and place (such as taking part in a marathon, sportive or group ride). An activity's recorded information may include a route summary, elevation (net and unidirectional), speed (average, minimum, maximum), timing (total and moving time), power and heart rate. Activities can be recorded using the mobile app or from devices manufactured by third parties like Garmin, Google Fit, Suunto, and Wahoo. Activities can also be entered manually via the Strava website.

Strava Metro, a program marketed towards city planners, uses cycling data from Strava users in supported cities and regions.[5][6]

History

Strava, which means "strive" in Swedish (although spelled "sträva" in Swedish with an "ä"), was founded in 2009. Cofounders Michael Horvath and Mark Gainey first met in the 1980s as members of Harvard University's rowing crew.[7]

Initially popular with cyclists and eventually runners, by 2017 over 1 billion activities had been uploaded to the service.[8] By 2020, Strava had more than 50 million users and three billion activities had been uploaded.[9]

In March 2022, Strava stopped operating in Russia and Belarus because of the Russian invasion of Ukraine.[10]

In early 2023, Strava significantly raised subscription prices in many markets—some more than doubling.[11][12] A month earlier, the company laid off approximately 14% of its workforce.[13] The company's last venture capital funding was a $110 million Series F in 2020.[14] In January 2023 Strava also acquired Fatmap, a company focused on building high-resolution 3D maps used for outdoor activities, with a long-term goal to integrate Fatmap’s core platform into Strava itself.[15]

In February 2023, founder and current CEO Michael Horvath announced that he would resign.[16][17]

Features and tools

Strava incorporates social media features which allow users to post their exercises to followers. Alongside a GPS map of their exercise users can also post pictures and videos. Followers can then comment on posts and give 'kudos' in the form of a like button.

Beacon is a feature that allows Strava users to share their location in real time with anyone they choose to, and nominate others as a safety contact for their workout. Other premium features include access to custom route-building tools and access to map segment leaderboards.

Strava maintains a system of leaderboards that show the most frequent runners or riders on a segment, as well as the fastest times by activity type. These fastest segment times (also known as KOMs, for "King of the Mountain") have been widely criticized for including times by athletes banned for doping, as well as fake times logged by motorized vehicles and other forms of cheating.[18][19][20] In response, Strava released tools for users to report suspicious activities.[21]

Privacy concerns

In November 2017, Strava published a "Global Heatmap"—a "visualization of two years of trailing data from Strava's global network of athletes."[22] In January 2018, an Australian National University student studying international security discovered that this map had mapped military bases, including known U.S. bases in Syria, and forward operating bases in Afghanistan, and HMNB Clyde—a Royal Navy base that contains the United Kingdom's nuclear arsenal.[23][24][25][26] The findings led to continued scrutiny over privacy issues associated with fitness services and other location-aware applications; Strava's CEO James Quarles stated that the company was "committed to working with military and government officials" on the issue, and would be reviewing its features and simplifying its privacy settings.[27][28] Although users can now opt out of having their data aggregated on the global heatmap, the original data that contains sensitive information has been archived on GitHub.[29][30]

A separate security flaw was reported in June 2022 that allowed the identification and tracking of security personnel working at military bases in Israel. Distinct from the previous heatmap issue, this vulnerability relied on Strava's segments feature.[31]

In June 2023, a report claimed that Strava heat map data could be used to reveal the home addresses of highly active users in remote areas.[32]

In August 2023, Strava was used to identify James Dennis White Jr. as the alleged arsonist in an attack on a President Donald Trump supporter. [33]

References

- "Strava: Track Running, Cycling & Swimming APKs – APKMirror". APKMirror.

- "Strava: Run, Ride, Swim". App Store. July 26, 2023.

- "Changing your language in the Strava App". Strava. Retrieved November 10, 2018.

- "Supported Activity Types on Strava". Strava Support. Retrieved November 10, 2018.

- Walker, Peter (May 9, 2016). "City planners tap into wealth of cycling data from Strava tracking app". The Guardian. Retrieved November 10, 2018.

- MacMichael, Simon (May 7, 2014). "Strava moves into 'big data' – London & Glasgow already signed up to find out where cyclists ride". Road.cc. Retrieved December 1, 2014.

- George, Rose (January 14, 2020). "Kudos, leaderboards, QOMs: how fitness app Strava became a religion". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved February 5, 2023.

- Hichens, Liz (May 24, 2017). "A Triathlete Just Uploaded Strava's One-Billionth Activity". Triathlete. Retrieved February 5, 2023.

- "Strava now has 50 million users". Cyclist. February 11, 2020. Retrieved February 5, 2023.

- Dress, Bradley (March 11, 2022). "Strava ending service in Russia, Belarus". The Hill. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- "Strava hikes monthly subscription price by more than 25 per cent". BikeRadar. January 6, 2023. Retrieved February 5, 2023.

- Song, Victoria (January 13, 2023). "Strava knows its messy price hike is confusing". The Verge. Retrieved February 5, 2023.

- "Strava Lays Off Employees, Significantly Raises Prices". Runner's World. January 13, 2023. Retrieved February 5, 2023.

- Etherington, Darrell (November 16, 2020). "Strava raises $110 million, touts growth rate of 2 million new users per month in 2020". TechCrunch. Retrieved February 5, 2023.

- "Strava acquires Fatmap, a 3D mapping platform for the great outdoors". TechCrunch. January 24, 2023.

- Vern Pitt (February 13, 2023). "Strava starts race to find new CEO". cyclingweekly.com. Retrieved February 13, 2023.

- Sawers, Paul (February 13, 2023). "Strava searches for new CEO with co-founder Michael Horvath departing for a second time". TechCrunch. Retrieved February 14, 2023.

- Paresh, Dave (April 18, 2016). "Fitness app Strava faces an uproar over an elite cycling user linked to doping". Los Angeles Times.

- "Strava KOMS are being hijacked by motorbikers going as fast as 112mph". road.cc. September 20, 2022. Retrieved March 3, 2023.

- Usborne, Simon (June 1, 2016). "Dope and glory: the rise of cheating in amateur sport". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved March 3, 2023.

- "How to Report Cheating on Strava". Strava Support. August 31, 2022.

- Robb, Drew (April 4, 2018). "Building the Global Heatmap – strava-engineering". Strava Engineering. Retrieved July 13, 2019.

- Hern, Alex (January 23, 2018). "Fitness tracking app gives away location of secret US army bases". The Guardian. Retrieved January 28, 2018.

- "Fitness tracker highlights military bases". BBC News. 2018. Retrieved January 29, 2018.

- "Strava Endangering the Military Accidentally". Crash Security. January 28, 2018. Archived from the original on May 22, 2018. Retrieved May 21, 2018.

- Liptak, Andrew (January 28, 2018). "Strava's fitness tracker heat map reveals the location of military bases". The Verge. Retrieved July 13, 2019.

- "Strava's fitness heatmaps are a 'potential catastrophe'". Engadget. Retrieved July 13, 2019.

- "Strava will focus on privacy awareness to address security issues". Engadget. Retrieved July 13, 2019.

- Hern, Alex (January 29, 2018). "Strava suggests military users 'opt out' of heatmap as row deepens". The Guardian. Retrieved April 2, 2020.

- Schwartz, Mathew (January 28, 2018). "Feel the Heat: Strava 'Big Data' Maps Sensitive Locations". www.bankinfosecurity.com. Retrieved April 2, 2020.

- "Strava app flaw revealed runs of Israeli officials at secret bases". BBC News. June 21, 2022. Retrieved June 22, 2022.

- "Strava responds to alarming report suggesting that it could be used to track you down". The Independent. June 14, 2023. Retrieved June 27, 2023.

- https://www.cyclingweekly.com/news/strava-used-to-identify-cyclist-who-burned-down-donald-trump-supporters-sign