Star Wars (film)

Star Wars (retroactively retitled Star Wars: Episode IV – A New Hope) is a 1977 American epic space opera film written and directed by George Lucas, produced by Lucasfilm and distributed by 20th Century-Fox. It was the first film released in the Star Wars film series and the fourth chronological chapter of the "Skywalker Saga". Set "a long time ago" in a fictional universe where the galaxy is ruled by the tyrannical Galactic Empire, the story focuses on a group of freedom fighters known as the Rebel Alliance, who aim to destroy the Empire's newest weapon, the Death Star. When Rebel leader Princess Leia is apprehended by the Empire, Luke Skywalker acquires stolen architectural plans of the Death Star and sets out to rescue her while learning the ways of a metaphysical power known as "the Force" from Jedi Master Obi-Wan Kenobi. The cast includes Mark Hamill, Harrison Ford, Carrie Fisher, Peter Cushing, Alec Guinness, David Prowse, James Earl Jones, Anthony Daniels, Kenny Baker, and Peter Mayhew.

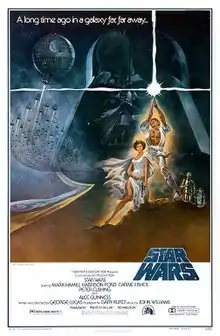

| Star Wars | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster by Tom Jung | |

| Directed by | George Lucas |

| Written by | George Lucas |

| Produced by | Gary Kurtz |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Gilbert Taylor |

| Edited by | |

| Music by | John Williams |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | 20th Century-Fox |

Release date |

|

Running time | 121 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States[2] |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $11 million[3][4] |

| Box office | $775.8 million[3] |

Lucas had the idea for a science-fiction film in the vein of Flash Gordon around the time he completed his first film, THX 1138 (1971), and began working on a treatment after the release of American Graffiti (1973). After numerous rewrites, filming took place throughout 1975 and 1976 in locations including Tunisia and Elstree Studios in Hertfordshire, England. The film suffered production difficulties; the cast and crew involved believed the film would be a failure. Lucas formed the visual effects company Industrial Light & Magic to help create the film's special effects. It also went $3 million over budget due to delays.

Star Wars was released in a limited number of theaters in the United States on May 25, 1977, and quickly became a blockbuster hit, leading to it being expanded to a much wider release. The film opened to critical acclaim for its acting, direction, story, musical score, action sequences, sound, editing, screenplay, costume design, and production values, but particularly for its groundbreaking visual effects. It grossed $410 million worldwide during its initial run, surpassing Jaws (1975) to become the highest-grossing film until the release of E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial (1982); subsequent releases brought its total gross to $775 million. When adjusted for inflation, Star Wars is the second-highest-grossing film in North America (behind Gone with the Wind) and the fourth-highest-grossing film of all time. It received numerous awards at the Academy Awards, BAFTA Awards, and Saturn Awards, among others. The film has been reissued many times with Lucas's support—most significantly with its 20th-anniversary theatrical "Special Edition"—incorporating many changes including modified computer-generated effects, altered dialogue, re-edited shots, remixed soundtracks and added scenes.

Often regarded as one of the greatest and most influential films ever made, the film became a pop-cultural phenomenon, launching an industry of tie-in products, including novels, comics, video games, amusement park attractions and merchandise including toys, games, and clothing. It became one of the first 25 films selected by the United States Library of Congress for preservation in the National Film Registry in 1989, while its soundtrack was added to the U.S. National Recording Registry in 2004. The Empire Strikes Back (1980) and Return of the Jedi (1983) followed Star Wars, rounding out the original Star Wars trilogy. A prequel and a sequel trilogy have since been released, in addition to two anthology films and various television series.

Plot

Amid a galactic civil war, Rebel Alliance spies have stolen plans to the tyrannical Galactic Empire's Death Star, a massive space station capable of destroying entire planets. Imperial Senator Princess Leia Organa of Alderaan, secretly one of the Rebellion's leaders, has obtained its schematics, but her ship is intercepted by an Imperial Star Destroyer under the command of the ruthless Darth Vader. Before she is captured, Leia hides the plans in the memory system of astromech droid R2-D2, who flees in an escape pod to the nearby desert planet Tatooine alongside his companion, protocol droid C-3PO.

The droids are captured by Jawa traders, who sell them to moisture farmers Owen and Beru Lars and their nephew Luke Skywalker. While Luke is cleaning R2-D2, he discovers a holographic recording of Leia requesting help from one Obi-Wan Kenobi. Later, R2-D2 is missing, and while searching for him, Luke is attacked by scavenging Sand People. He is rescued by elderly hermit Obi-Wan Kenobi, who tells Luke of his days as one of the Jedi Knights, former peacekeepers of the Galactic Republic, who drew mystical abilities from a metaphysical energy field known as "the Force", but were ultimately hunted to near-extinction by the Empire. Luke learns that his father fought alongside Obi-Wan as a Jedi Knight during the Clone Wars until Vader, Obi-Wan's former pupil, turned to the dark side of the Force and murdered him. Obi-Wan offers Luke his father's old lightsaber, the signature weapon of Jedi Knights.

R2-D2 plays Leia's full message, in which she begs Obi-Wan to take the Death Star plans to Alderaan and give them to her father, a fellow veteran, for analysis. Although Luke initially declines Obi-Wan's offer to accompany him to Alderaan and learn the ways of the Force, he is left with no choice after discovering that Imperial stormtroopers have killed his aunt and uncle and destroyed their farm in their search for the droids. Traveling to a cantina in Mos Eisley to search for transport, Luke and Obi-Wan hire Han Solo, a smuggler indebted to local mobster Jabba the Hutt. Pursued by stormtroopers, Obi-Wan, Luke, R2-D2, and C-3PO flee Tatooine with Han and his Wookiee co-pilot Chewbacca on their ship, the Millennium Falcon.

Before the Falcon can reach Alderaan, Death Star commander Grand Moff Tarkin destroys the planet after interrogating Leia for the location of the Rebel Alliance's base. Upon arrival, the Falcon is captured by the Death Star's tractor beam, but the group evades capture by hiding in the ship's smuggling compartments. As Obi-Wan leaves to disable the tractor beam, Luke persuades Han and Chewbacca to help him rescue Leia after discovering that she is scheduled to be executed. After disabling the tractor beam, Obi-Wan sacrifices himself in a lightsaber duel against Vader, allowing the rest of the group to escape the Death Star with Leia. Using a tracking device, the Empire tracks the Falcon to the hidden Rebel base on Yavin IV.

The schematics reveal a hidden weakness in the Death Star's thermal exhaust port, which could allow the Rebels to trigger a chain reaction in its main reactor with a precise proton torpedo strike. Han leaves the Rebels to pay off Jabba, after collecting his reward for rescuing Leia. Luke joins their X-wing starfighter squadron in a desperate attack against the approaching Death Star. In the ensuing battle, the Rebels suffer heavy losses as Vader leads a squadron of TIE fighters against them. Han and Chewbacca unexpectedly return to aid them in the Falcon, and knock Vader's ship off course before he can shoot Luke down. Guided by the voice of Obi-Wan's spirit, Luke uses the Force to aim his torpedoes into the exhaust port, destroying the Death Star moments before it fires on the Rebel base. In a triumphant ceremony at the base, Leia awards Luke and Han medals for their heroism.

Cast

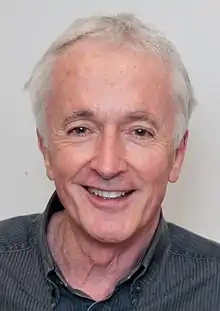

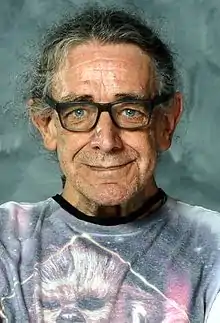

Middle: Anthony Daniels (2011), Kenny Baker (2012), Peter Mayhew (2015)

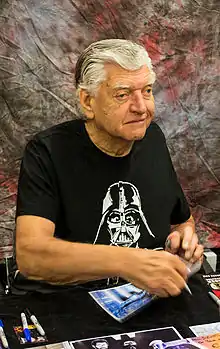

Bottom: David Prowse (2013), James Earl Jones (2013), Alec Guinness (1973)

- Mark Hamill as Luke Skywalker: A young adult raised by his aunt and uncle on Tatooine, who dreams of something more than his current life and learns about the Force and the Jedi. Lucas favored casting young actors who lacked long experience. To play Luke (then known as Luke Starkiller), Lucas sought actors who could project intelligence and integrity. While reading the script, Hamill found the dialogue to be extremely odd because of its universe-embedded concepts. He chose to simply read it sincerely, and he was cast instead of William Katt, who was subsequently cast in Brian De Palma's Carrie (Lucas shared a joint casting session with De Palma, a longtime friend).[5][6] Robby Benson, Will Seltzer, Charles Martin Smith and Kurt Russell also auditioned for the role.[7][8][9][10][11]

- Harrison Ford as Han Solo: A cynical smuggler and captain of the Millennium Falcon. Lucas initially rejected casting Ford for the role, as he "wanted new faces"; Ford had previously worked with Lucas on American Graffiti. Instead, Lucas asked Ford to assist in the auditions by reading lines with the other actors and explaining the concepts and history behind the scenes that they were reading. Lucas was eventually won over by Ford's portrayal and cast him instead of Kurt Russell, Nick Nolte,[6] Sylvester Stallone,[12] Bill Murray,[13][14] Christopher Walken, Burt Reynolds, Jack Nicholson, James Caan,[15] Robert De Niro, Kelsey Grammer,[16] Al Pacino, Steve Martin, Chevy Chase, or Perry King (who later played Han Solo in the radio plays).[5][17][18]

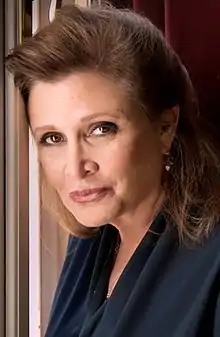

- Carrie Fisher as Princess Leia Organa: The princess of the planet Alderaan who is a member of the Imperial Senate and, secretly, one of the leaders of the Rebel Alliance. Many young Hollywood actresses auditioned for the role of Princess Leia, including Amy Irving,[6] Terri Nunn, Cindy Williams,[5] Linda Purl,[19] Karen Allen,[6] and Jodie Foster.[20][21][22] Koo Stark was considered but ended up getting the role of Camie Marstrap, Luke Skywalker's friend, a character that did not make the final cut of the film.[23][24][lower-alpha 1] Fisher was cast under the condition that she lose 10 pounds (4.5 kg) for the role.[26]

- Peter Cushing as Grand Moff Tarkin: The commander of the Death Star. Lucas originally offered the role to Christopher Lee but he declined.[27] Lucas originally had Cushing in mind for the role of Obi-Wan Kenobi, but Lucas believed that "his lean features" would be better employed in the role of Tarkin instead. Lucas commended Cushing's performance, saying "[He] is a very good actor. Adored and idolized by young people and by people who go to see a certain kind of movie. I feel he will be fondly remembered for the next 350 years at least." Cushing, commenting on his role, joked: "I've often wondered what a 'Grand Moff' was. It sounds like something that flew out of a cupboard."[28]

- Alec Guinness as Obi-Wan Kenobi: An aging Jedi Master and veteran of the Clone Wars who introduces Luke to the Force. Lucas's decision to cast "unknowns" was not taken favorably by his friend Francis Ford Coppola and the studio, so Lucas decided Obi-Wan Kenobi should be played by an established actor. Producer Gary Kurtz said, "The Alec Guinness role required a certain stability and gravitas as a character... which meant we needed a very, very strong character actor to play that part."[5] Before Guinness was cast, Japanese actor Toshiro Mifune (who starred in many Akira Kurosawa films) was considered for the role.[6][29] According to Mifune's daughter, Mika Kitagawa, her father turned down Lucas' offers to play Kenobi and Darth Vader because "he was concerned about how the film would look and that it would cheapen the image of samurai... At the time, sci-fi movies still looked quite cheap as the effects were not advanced and he had a lot of samurai pride."[30] Guinness was one of the few cast members who believed that the film would be successful; he negotiated a deal for 2.25% of the one-fifth gross royalties paid to Lucas, which made him quite wealthy in later life. He agreed to take the part of Kenobi on the condition that he would not have to do any publicity to promote the film.[31] Lucas credited him with inspiring the cast and crew to work harder, saying that Guinness contributed significantly to the completion of the filming.[32] Harrison Ford said, "It was, for me, fascinating to watch Alec Guinness. He was always prepared, always professional, always very kind to the other actors. He had a very clear head about how to serve the story."[5]

- Anthony Daniels as C-3PO: A protocol droid affiliated with the Rebellion who is "fluent in over six million forms of communication". Daniels auditioned for and was cast as C-3PO; he has said that he wanted the role after he saw a Ralph McQuarrie drawing of the character and was struck by the vulnerability in the robot's face.[5][33] Initially, Lucas did not intend to use Daniels' voice for C-3PO. Thirty well-established voice actors read for the voice of the droid. According to Daniels, one of the major voice actors, believed by some sources to be Stan Freberg, recommended Daniels' voice for the role.[5][34] Mel Blanc was considered for the role, but according to Daniels, Blanc told Lucas that Daniels was better for the part.[7][35] Richard Dreyfuss was also considered.[36]

- Kenny Baker as R2-D2: An astromech droid and C-3PO's companion, who is carrying the Death Star plans and a secret message for Obi-Wan from Princess Leia. When filming was under way in London, where additional casting took place, Baker, performing a musical comedy act with his acting partner Jack Purvis, learned that the film crew was looking for a small person to fit inside a robot suit and maneuver it. Baker, who was 3 feet 8 inches (1.12 m) tall, was cast immediately after meeting George Lucas. He said, "He saw me come in and said 'He'll do' because I was the smallest guy they'd seen up until then." He initially turned down the role three times, hesitant to appear in a film where his face would not be shown and hoping to continue the success of his comedy act, which had recently started to be televised.[37] R2-D2's recognizable beeps and squeaks were made by sound designer Ben Burtt imitating "baby noises", recording this voice as it was heard on an intercom, and creating the final mix using a synthesizer.[38]

- Peter Mayhew as Chewbacca: A Wookiee, Han Solo's sidekick, and first mate of the Millennium Falcon. Mayhew learned of a casting call for Star Wars, which was being shot in London, and decided to audition. The 7-foot-3-inch (2.21 m) tall actor was immediately cast as Chewbacca after he stood up to greet Lucas.[5][39] He recounted, "I sat down on one of the sofas, waiting for George. Door opened, and George walked in with Gary behind him. So, naturally, what did I do? I'm raised in England. Soon as someone comes in through the door, I stand up. George goes 'Hmm [looked up].' Virtually turned to Gary, and said 'I think we've found him.'[5] Mayhew originally auditioned for Darth Vader, but David Prowse was cast instead.[39][40] Mayhew modeled his performance of Chewbacca after the mannerisms of animals he saw at public zoos.[31]

- David Prowse as Darth Vader: Obi-Wan's former Jedi apprentice, who fell to the dark side of the Force. Prowse was originally offered the role of Chewbacca, but turned it down as he wanted to play the villain instead.[41] Lucas dismissed Prowse for the character's voice due to his West Country English accent, which led to him being nicknamed "Darth Farmer" by the other cast members.[38]

- James Earl Jones as the voice of Darth Vader; he was uncredited until 1983. Lucas originally intended for Orson Welles to voice the character after dismissing Prowse.[38] However, determining that Welles' voice would be too familiar to audiences, Lucas instead cast then-relatively less recognizable Jones.[5][6]

Other actors include Phil Brown and Shelagh Fraser as Luke's Uncle Owen and Aunt Beru; Jack Purvis, Kenny Baker's partner in his London comedy act, as the Chief Jawa in the film; and Eddie Byrne as Vanden Willard, a Rebel general.[42] Denis Lawson and Garrick Hagon played rebel pilots Wedge Antilles and Biggs Darklighter (Luke's childhood friend), respectively. Don Henderson and Leslie Schofield appear as Imperial Generals Cassio Tagge and Moradmin Bast, respectively, and Richard LeParmentier plays Admiral Motti.[43] Alex McCrindle portrays General Jan Dodonna, Alfie Curtis portrays Dr. Evazan, and Peter Geddis portrays Captain Raymus Antilles. Michael Leader plays a minor role as a Stormtrooper known for accidentally hitting his helmet against a door.[44][45] Heavily synthesised audio recordings of John Wayne from earlier films were used as the voice of the Imperial spy Garindan.[46][47] Robert Clarke appears as Imperial officer Wulff Yularen and Patrick Jordan plays another Imperial officer, Siward Cass.

Production

Development

Lucas had the idea for a space-fantasy film in 1971, after he completed directing his first full-length feature, THX 1138.[49] Originally, Lucas wanted to adapt the Flash Gordon space adventure comics and serials into his own films, having been fascinated by them since he was young.[50] He later said:

I especially loved the Flash Gordon serials ... Of course I realize now how crude and badly done they were ... loving them that much when they were so awful, I began to wonder what would happen if they were done really well.[51]

At the Cannes Film Festival following the completion of THX 1138, Lucas pushed towards buying the Flash Gordon rights, but they were already tied-up with Dino De Laurentiis.[51] Lucas later recounted:

I wanted to make a Flash Gordon movie, with all the trimmings, but I couldn't obtain the rights to the characters. So I began researching and went right back and found where Alex Raymond (who had done the original Flash Gordon comic strips in newspapers) had got his idea from. I discovered that he'd got his inspiration from the works of Edgar Rice Burroughs (author of Tarzan) and especially from his John Carter of Mars series books. I read through that series, then found that what had sparked Burroughs off was a science fantasy called Gulliver on Mars, written by Edwin Arnold and published in 1905. That was the first story in this genre that I have been able to trace. Jules Verne had got pretty close, I suppose, but he never had a hero battling against space creatures or having adventures on another planet. A whole new genre developed from that idea.[49]

Director Francis Ford Coppola, who accompanied Lucas in trying to buy the Flash Gordon rights, recounted in 1999: "[George] was very depressed because he had just come back and they wouldn't sell him Flash Gordon. And he says, 'Well, I'll just invent my own.'"[51][52] He secured a two-film development deal with United Artists; the two films were American Graffiti and a space opera, tentatively titled "The Star Wars" and inspired by Flash Gordon.[53] Lucas would later say that he had the idea for an original space opera long before 1971,[54] and that he even tried to film it before American Graffiti.[55] Believing that the bleak tone of THX 1138 led to its poor reception, Lucas chose to make Star Wars more optimistic; this is what led to its fun and adventurous tone.[56]

_2.jpg.webp)

Lucas went to United Artists and showed them the script for American Graffiti, but they passed on the film, which was then picked up by Universal Pictures.[52] United Artists also passed on Lucas's space-opera concept, which he shelved for the time being.[57] After spending the next two years completing American Graffiti, Lucas turned his attention to his space opera.[49][52] He drew inspiration from politics of the era, later saying, "It was really about the Vietnam War, and that was the period where Nixon was trying to run for a [second] term."[58][59]

Lucas began writing in January 1973, "eight hours a day, five days a week",[49] by taking small notes, inventing odd names and assigning them possible characterizations. Lucas would discard many of these by the time the final script was written, but he included several names and places in the final script or its sequels. He used these initial names and ideas to compile a two-page synopsis titled Journal of the Whills, which told the tale of the training of apprentice CJ Thorpe as a "Jedi-Bendu" space commando by the legendary Mace Windy.[60] Frustrated that his story was too difficult to understand,[61] Lucas then began writing a 13-page treatment called The Star Wars on April 17, 1973, which had narrative parallels with Kurosawa's 1958 film The Hidden Fortress.[62]

While impressed with the "innocence of the story, plus the sophistication of the world"[55] of the film, United Artists declined to budget the film. Lucas and producer Gary Kurtz presented the film treatment to Universal Pictures, the studio that financed American Graffiti; while they agreed it could be "a very commercial venture", they had doubts about Mr. Lucas's ability to pull it all off,[55] and said that Lucas should follow American Graffiti with more consequential themes.[48] Coppola brought the project to a division of Paramount Pictures he ran with fellow directors Peter Bogdanovich and William Friedkin, but Friedkin questioned Lucas's ability to direct the film and he, along with Bogdanovich, declined to back it.[63]

Lucas said, "I've always been an outsider to Hollywood types. They think I do weirdo films."[48] According to Kurtz, Lew Wasserman, the head of Universal, "just didn't think much of science fiction at that time, didn't think it had much of a future then, with that particular audience."[64] He said that "science fiction wasn't popular in the mid-'70s ... what seems to be the case generally is that the studio executives are looking for what was popular last year, rather than trying to look forward to what might be popular next year."[65] Kurtz said, "Although Star Wars wasn't like [then-current science fiction] at all, it was just sort of lumped into that same kind of category."[64]

Lucas explained in 1977 that the film is not "about the future" and that it "is a fantasy much closer to the Brothers Grimm than it is to 2001." He added: "My main reason for making it was to give young people an honest, wholesome fantasy life, the kind my generation had. We had Westerns, pirate movies, all kinds of great things. Now they have The Six Million Dollar Man and Kojak. Where are the romance, the adventure, and the fun that used to be in practically every movie made?"[48] Lucas would later recontextualize the discussion around the film, saying it was born out of research into "psychological underpinnings of mythology", a claim that had been dismissed by Kurtz: "The whole idea of Star Wars as a mythological thing, I think came about because of [later Lucas] interviews that tied it to The Hero with a Thousand Faces"[66] and by Steven Hart and Michael Kaminski: "It is here that the true origin of Star Wars comes from – not from myth and legend, but from the 'schlock' sold on newspapers stands and played in matinees."[67]

There were also concerns regarding the project's potentially high budget. Lucas and Kurtz, in pitching the film, said that it would be "low-budget, Roger Corman style, and the budget was never going to be more than—well, originally we had proposed about 8 million, it ended up being about 10. Both of those figures are very low budget by Hollywood standards at the time."[64] After Walt Disney Productions turned down the project, Lucas and Kurtz persisted in securing a studio to support the film because "other people had read it and said, 'Yeah, it could be a good idea.'"[64] Lucas pursued Alan Ladd Jr., the head of 20th Century-Fox, and in June 1973 completed a deal to write and direct the film. Although Ladd did not grasp the technical side of the project, he believed that Lucas was talented. Lucas later stated that Ladd "invested in me, he did not invest in the movie."[5] The deal gave Lucas $150,000 to write and direct the film.[31] American Graffiti's positive reception afforded Lucas the leverage necessary to renegotiate his deal with Ladd and request the sequel rights to the film in August 1973. For Lucas, this deal protected Star Wars's potential sequels and most of the merchandising profits.[5]: 19

Writing

It's the flotsam and jetsam from the period when I was twelve years old. All the books and films and comics that I liked when I was a child. The plot is simple—good against evil—and the film is designed to be all the fun things and fantasy things I remember. The word for this movie is fun.

—George Lucas, 1977[48]

Since commencing his writing process in January 1973, Lucas had done "various rewrites in the evenings after the day's work." He would write four different screenplays for Star Wars, "searching for just the right ingredients, characters and storyline. It's always been what you might call a good idea in search of a story."[49] By May 1974, he had expanded the treatment for The Star Wars into a rough draft screenplay,[5]: 14 [68] adding elements such as the Sith, the Death Star, and a general by the name of Annikin Starkiller. He changed Starkiller to an adolescent boy, and he shifted the general into a supporting role as a member of a family of dwarfs.[5][34] Lucas envisioned the Corellian smuggler, Han Solo, as a large, green-skinned monster with gills. He based Chewbacca on his Alaskan Malamute dog, Indiana (whom he would later use as eponym for his character Indiana Jones), who often acted as the director's "co-pilot" by sitting in the passenger seat of his car.[34][69]

Lucas completed a second draft in January 1975 as Adventures of the Starkiller, Episode One: The Star Wars, making heavy simplifications and introducing the young hero on a farm as Luke Starkiller. Annikin became Luke's father, a wise Jedi knight. "The Force" was also introduced as a mystical energy field.[68] This draft still had some differences from the final version in the characters and relationships. For example, Luke had several brothers, as well as his father, who appears in a minor role at the end of the film. The script became more of a fairy tale quest as opposed to the action/adventure of the previous versions. This version ended with another text crawl, previewing the next story in the series. This draft was also the first to introduce the concept of a Jedi turning to the dark side: the draft included a historical Jedi who was the first to ever fall to the dark side, and then trained the Sith to use it. The script would introduce the concept of a Jedi Master and his son, who trains to be a Jedi under his father's friend; this would ultimately form the basis for the film and, later, the trilogy. However, in this draft, the father is a hero who is still alive at the start of the film.[70] Han Solo and Chewbacca's identities closely resembled those seen in the finished film.[71] According to Lucas, the second draft was over 200 pages long, and led him to split up the story into multiple films spanning over multiple trilogies.[72]

Lucas began to rewrite this draft, creating a synopsis for the third draft. During work on this rewrite, Lucas began researching the science-fiction genre by watching films and reading books (including J. R. R. Tolkien's The Hobbit)[73][74] and comics.[75] He also claims to have read scholastic works like Joseph Campbell's The Hero with a Thousand Faces,[76] James George Frazer's The Golden Bough,[73] and even Bruno Bettelheim's The Uses of Enchantment.[77] These claims are doubted by Michael Kaminski and Chris Taylor, with Kaminski pointing out that Bettelheim's book would not come out until after Star Wars was filmed and adding that "the original trilogy-Campbell connection is greatly exaggerated and practically non-existent",[77] noting that, in fact, the second draft is "even closer to Campbell's structure" than the third.[77]

According to Lucas, he wrote a rough draft of about 250–300 pages long, which contained the outline for the entire original Star Wars trilogy. He realized that it was too long for a single film, and decided to subdivide it into a trilogy.[5][78][79] Lucas stated that the story evolved over time and that "There was never a script completed that had the entire story as it exists now [in 1983] ... As the stories unfolded, I would take certain ideas and save them ... I kept taking out all the good parts, and I just kept telling myself I would make other movies someday."[80] He later described that, having split the script into three episodes, "the first part didn't really work",[81] so he had to take the ending off of Episode VI and put it in the original Star Wars, which resulted in a Death Star being included in both films.[82][lower-alpha 2] In 1975, Lucas suggested he could make a trilogy, which "ends with the destruction of the Empire" and a possible prequel "about the backstory of Kenobi as a young man". After the film's smash success,[85] Lucasfilm announced that Lucas had already written "twelve stories in the Adventures of Luke Skywalker"[86] which, according to Kurtz, were set to be "separate adventures rather than direct sequels."[87]

During the writing of the third draft, Lucas hired conceptual artist Ralph McQuarrie to create paintings of certain scenes, several of which Lucas included with his screenplay when he delivered it to 20th Century-Fox.[88] On February 27, the studio granted a budget of $5 million; this was later increased to $8.25 million.[5]: 17:30 Subsequently, Lucas started writing with a budget in mind, conceiving the cheap, "used" look of much of the film, and (with Fox having just shut down its special effects department) reducing the number of complex special effects shots called for by the script.[73] The third draft, dated August 1, 1975, was titled The Star Wars From the Adventures of Luke Starkiller. This third draft had most of the elements of the final plot, with only some differences in the characters and settings. The draft characterized Luke as an only child, with his father already dead, replacing him with a substitute named Ben Kenobi.[68] This script would be re-written for the fourth and final draft, dated January 1, 1976, as The Adventures of Luke Starkiller as taken from the Journal of the Whills, Saga I: The Star Wars. Lucas worked with his friends Gloria Katz and Willard Huyck to revise the fourth draft into the final pre-production script.[89]

Lucas finished writing his script in March 1976, when the crew started filming. He said, "What finally emerged through the many drafts of the script has obviously been influenced by science-fiction and action-adventure I've read and seen. And I've seen a lot of it. I'm trying to make a classic sort of genre picture, a classic space fantasy in which all the influences are working together. There are certain traditional aspects of the genre I wanted to keep and help perpetuate in Star Wars."[49] During production, he changed Luke's name from Starkiller to Skywalker[5] and altered the title to The Star Wars and later Star Wars.[68] He would also continue to tweak the script during filming, including adding the death of Obi-Wan after realizing he served no purpose in the ending of the film.[90][91]

For the film's opening crawl, Lucas originally wrote a composition consisting of six paragraphs with four sentences each.[31][92] He said, "The crawl is such a hard thing because you have to be careful that you're not using too many words that people don't understand. It's like a poem." Lucas showed his draft to his friends.[93] Director Brian De Palma, who was there, described it: "The crawl at the beginning looks like it was written on a driveway. It goes on forever. It's gibberish."[94] Lucas recounted what De Palma said the first time he saw it: "George, you're out of your mind! Let me sit down and write this for you." De Palma and Jay Cocks helped edit the text into the form used in the film.[93][95]

Design

George Lucas recruited many conceptual designers, including Colin Cantwell, who worked on 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), to conceptualize the initial spacecraft models; Alex Tavoularis to create the preliminary conceptual storyboard sketches of early scripts; and Ralph McQuarrie to visualize the characters, costumes, props, and scenery.[49] McQuarrie's pre-production paintings of certain scenes from Lucas's early screenplay drafts helped 20th Century-Fox visualize the film, which positively influenced their decision to fund the project. After McQuarrie's drawings for Lucas's colleagues Hal Barwood and Matthew Robbins (who were collaborating for a film) caught his interest, Lucas met with McQuarrie to discuss his plans for the untitled space fantasy film he wanted to make. Two years later, after completing American Graffiti, Lucas approached McQuarrie and asked him if he would be interested "in doing something for Star Wars."[96] McQuarrie produced a series of artworks from simple sketches; these set a visual tone for the film, and for the rest of the original trilogy.[49]

Star Wars has no points of reference to Earth time or space, with which we are familiar, and it is not about the future but some galactic past or some extra-temporal present, it is a decidedly inhabited and used place where the hardware is taken for granted.

—Lucas on his "used future" backdrop[97]

The film was ambitious as Lucas wanted to create fresh prop prototypes and sets (based on McQuarrie's paintings) that had never been realized before in science fiction films. He commissioned production designers John Barry and Roger Christian, who were working on the sets of the film Lucky Lady (1975) when Lucas first approached them, to work on the production sets. Christian recounted in 2014: "George came to the set I was doing, it was an old salt factory design and he helped me shovel salt, just like two students in plaid shirts and sneakers. And we spoke and he looked at the set and couldn't believe it wasn't real." They had a conversation with Lucas on what he would like the film to appear like, with them creating the desired sets. Christian said that Lucas "didn't want anything [in Star Wars] to stand out, he wanted it [to look] all real and used. And I said, 'Finally somebody's doing it the right way.'"[98]

Lucas described a "used future" concept to the production designers in which all devices, ships, and buildings to do with Tatooine or the Rebels looked aged and dirty,[5][99][100] as opposed to the sleeker designs of the Empire. Lucas also wanted the spaceships to look "cobbled together, as opposed to a sleek monoshape."[101] Barry said that the director "wants to make it look like it's shot on location on your average everyday Death Star or Mos Eisley Spaceport or local cantina." Lucas believed that "what is required for true credibility is a used future", opposing the interpretation of "future in most futurist movies" that "always looks new and clean and shiny."[97] Christian supported Lucas's vision, saying "All science fiction before was very plastic and stupid uniforms and Flash Gordon stuff. Nothing was new. George was going right against that."[98]

The designers started working with the director before Star Wars was approved by 20th Century-Fox.[98] For four to five months, in a studio in Kensal Rise, England,[98][102] they attempted to plan the creation of the props and sets with "no money." Although Lucas initially provided funds using his earnings from American Graffiti, it was inadequate. As they could not afford to dress the sets, Christian was forced to use unconventional methods and materials to achieve the desired look. He suggested that Lucas use scrap in making the dressings, and the director agreed.[98] Christian said, "I've always had this idea. I used to do it with models when I was a kid. I'd stick things on them and we'd make things look old."[102] Barry, Christian, and their team began designing the props and sets at Elstree Studios.[97]

According to Christian, the Millennium Falcon set was the most difficult to build. Christian wanted the interior of the Falcon to look like that of a submarine.[98] He found scrap airplane metal "that no one wanted in those days and bought them."[102] He began his creation process by breaking down jet engines into scrap pieces, giving him the chance to "stick it in the sets in specific ways."[98] It took him several weeks to finish the chess set (which he described as "the most encrusted set") in the hold of the Falcon. The garbage compactor set "was also pretty hard, because I knew I had actors in there and the walls had to come in, and they had to be in dirty water and I had to get stuff that would be light enough so it wouldn't hurt them but also not bobbing around."[98] A total of 30 sets consisting of planets, starships, caves, control rooms, cantinas, and the Death Star corridors were created; all of the nine soundstages at Elstree were used to accommodate them. The massive rebel hangar set was housed at a second sound stage at Shepperton Studios; the stage was the largest in Europe at the time.[97]

Filming

In 1975, Lucas formed his own visual effects company Industrial Light & Magic (ILM) after discovering that 20th Century-Fox's visual effects department had been disbanded. ILM began its work on Star Wars in a warehouse in Van Nuys. Most of the visual effects used pioneering digital motion control photography developed by John Dykstra and his team, which created the illusion of size by employing small models and slowly moving cameras.[5] The technology is now known as the Dykstraflex system.[103][104] Brian Johnson also turned down the opportunity to work on the film because he was busy working on Space: 1999.[105]

Lucas tried "to get a cohesive reality" for his feature. Since the film is a fairy tale, as he had described, "I still wanted it to have an ethereal quality, yet be well composed and, also, have an alien look." He designed the film to have an "extremely bizarre, Gregg Toland-like surreal look with strange over-exposed colors, a lot of shadows, a lot of hot areas." Lucas wanted Star Wars to embrace the combination of "strange graphics of fantasy" and "the feel of a documentary" to impress a distinct look. To achieve this, he hired the British cinematographer Gilbert Taylor.[97] Originally, Lucas's first choice for the position was Geoffrey Unsworth, who also provided the cinematography for 2001: A Space Odyssey.[64] Unsworth was interested in working with the director, and initially accepted the job when it was offered to him by Lucas and Kurtz. He eventually withdrew to work on the Vincente Minnelli-directed A Matter of Time (1976) instead, which "really annoy[ed]" Kurtz.[64] Lucas called up for other cinematographers, and eventually chose Taylor, basing his choice on Taylor's cinematography for Dr. Strangelove and A Hard Day's Night (both 1964). On his decision, Lucas said: "I thought they were good, eccentrically photographed pictures with a strong documentary flavor."[97]

Taylor said that Lucas, who was consumed by the details of the complicated production, "avoided all meetings and contact with me from day one, so I read the extra-long script many times and made my own decisions as to how I would shoot the picture." Taylor also said, "I took it upon myself to experiment with photographing the lightsabers and other things onstage before we moved on to our two weeks of location work in Tunisia."[106] Taylor was aware of the "enormous amount of process work" to follow principal photography and believed "a crisp result would help."[107]

During production, Lucas and Taylor—whom Kurtz called "old-school" and "crotchety"[108]—had disputes over filming.[64] With a background in independent filmmaking, Lucas was accustomed to creating most of the elements of the film himself. His lighting suggestions were rejected by Taylor, who believed that Lucas was overstepping his boundaries by giving specific instructions, sometimes even moving lights and cameras himself. Taylor refused to use the soft-focus lenses and gauze Lucas wanted after Fox executives complained about the look.[108] Kurtz stated that "In a couple of scenes ... rather than saying, 'It looks a bit over lit, can you fix that?', [Lucas would] say, 'turn off this light, and turn off that light.' And Gil would say, 'No, I won't do that, I've lit it the way I think it should be—tell me what's the effect that you want, and I'll make a judgment about what to do with my lights.'"[64]

Originally, Lucas envisioned the planet of Tatooine, where much of the film would take place, as a jungle planet. Kurtz traveled to the Philippines to scout locations; however, because of the idea of spending months filming in the jungle would make Lucas "itchy", the director refined his vision and made Tatooine a desert planet instead.[109] Kurtz then researched all American, North African, and Middle Eastern deserts, and found Tunisia, near the Sahara desert, as the ideal location.[97] Lucas later stated that he had wanted to make it look like outer space.[110]

When principal photography began on March 22, 1976, in the Tunisian desert for the scenes on Tatooine, the project faced several problems.[111] Lucas fell behind schedule in the first week of shooting due to malfunctioning props and electronic breakdowns.[111][112] Moreover, a rare Tunisian rainstorm struck the country, which further disrupted filming. Taylor said, "you couldn't really see where the land ended and the sky began. It was all a gray mess, and the robots were just a blur." Given this situation, Lucas requested heavy filtration, which Taylor rejected, who said: "I thought the look of the film should be absolutely clean ... But George saw it differently, so we tried using nets and other diffusion. He asked to set up one shot on the robots with a 300 mm, and the sand and sky just mushed together. I told him it wouldn't work, but he said that was the way he wanted to do the entire film, all diffused." This difference was later settled by 20th Century-Fox executives, who backed Taylor's suggestion.[113]

Filming began in Chott el Djerid, while a construction crew in Tozeur took eight weeks to transform the desert into the desired setting.[97] Other locations included the sand dunes of the Tunisian desert near Nafta, where a scene featuring a giant skeleton of a creature lying in the background as R2-D2 and C-3PO make their way across the sands was filmed.[114] When Daniels wore the C-3PO outfit for the first time in Tunisia, the left leg piece shattered down through the plastic covering his left foot, stabbing him.[112] He also could not see through his costume's eyes, which was covered with gold to prevent corrosion.[109] Abnormal radio signals caused by the Tunisian sands made the radio-controlled R2-D2 models run out of control. Baker said: "I was incredibly grateful each time an [R2] would actually work right."[109] After several scenes were filmed against the volcanic canyons outside Tozeur, production moved to Matmata to film Luke's home on Tatooine. Lucas chose Hotel Sidi Driss, which is larger than the typical underground dwellings, to shoot the interior of Luke's homestead.[114] During the filming of the Jawa Sandcrawler, Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi, who did not have good relations with Tunisia at the time, allegedly mistook the crawler as a military vehicle to be utilized against him. When Gaddafi threatened the Tunisian Government, Lucas and the Tunisian Army quickly moved his filming crew to a more discreet location.[115] Additional scenes for Tatooine were filmed at Death Valley in North America.[116]

After two-and-a-half weeks of filming in Tunisia,[114] production moved to Elstree Studios, near London, to film interior scenes.[112] Elstree was chosen as a studio over other options in Hollywood or elsewhere. Star Wars required the use of nine different sound stages simultaneously, which most studios couldn't accommodate.[117] Because of stricter working conditions, filming in Britain had to finish by 5:30 pm, unless Lucas was in the middle of a scene.[31] He often made requests for more time to shoot, but they were usually turned down.[5]

Despite Lucas's efforts, his crew had little interest in the film. Most of the crew considered the project a "children's film", rarely took their work seriously, and often found it unintentionally humorous.[5][118] Actor Baker later confessed that he thought the film would be a failure. Ford found it strange that "there's a princess with weird buns in her hair", and called Chewbacca a "giant in a monkey suit."[5]

The Elstree sets designed by John Barry, according to Gilbert Taylor, "were like a coal mine." He said that "they were all black and gray, with really no opportunities for lighting at all." To resolve the problem, he worked the lighting into the sets by chopping in its walls, ceiling and floors. This would result in "a 'cut-out' system of panel lighting", with quartz lamps that could be placed in the holes in the walls, ceiling and floors. His idea was supported by the Fox studio, which agreed that "we couldn't have this 'black hole of Calcutta.'" The lighting approach Taylor devised "allowed George to shoot in almost any direction without extensive relighting, which gave him more freedom."[113] In total, the filming in Britain took 14+1⁄2 weeks.[114]

Lucas commissioned computer programmer Larry Cuba to create the animated Death Star plans shown at the rebel base on Yavin 4. This was written with the GRASS programming language, exported to a Vector General monitor and filmed on 35 mm to be rear-projected on the set. It is the only computer animation in the original version of the film.[119] The Yavin scenes were filmed in the Mayan temples at Tikal, Guatemala. Lucas selected the location as a potential filming site after seeing a poster of it hanging at a travel agency while he was filming in Britain. This inspired him to send a film crew to Guatemala in March 1977 to shoot scenes. While filming in Tikal, the crew paid locals with a six-pack of beer to watch over the camera equipment for several days.[120]

While shooting, Lucas rarely spoke to the actors, who believed that he expected too much of them while providing little direction. His directions to the actors usually consisted of the words "faster" and "more intense".[5] Kurtz stated that "it happened a lot where he would just say, 'Let's try it again a little bit faster.' That was about the only instruction he'd give anybody. A lot of actors don't mind—they don't care, they just get on with it. But some actors really need a lot of pampering and a lot of feedback, and if they don't get it, they get paranoid that they might not be doing a good job." Kurtz has said that Lucas "wasn't gregarious, he's very much a loner and very shy, so he didn't like large groups of people, he didn't like working with a large crew, he didn't like working with a lot of actors."[64]

Ladd offered Lucas some of the only support from the studio; he dealt with scrutiny from board members over the rising budget and complex screenplay drafts.[5][112] Initially, Fox approved $8 million for the project; Gary Kurtz said: "we proceeded to pick a production plan and do a more final budget with a British art department and look for locations in North Africa, and kind of pulled together some things. Then, it was obvious that 8 million wasn't going to do it—they had approved 8 million." After requests from the team that "it had to be more," the executives "got a bit scared."[64] For two weeks, Lucas and his crew "didn't really do anything except kind of pull together new budget figures." At the same time, after production fell behind schedule, Ladd told Lucas he had to finish production within a week or he would be forced to shut down production. Kurtz said that "it came out to be like 9.8 or .9 or something like that, and in the end they just said, 'Yes, that's okay, we'll go ahead.'"[64] The crew split into three units, with those units led by Lucas, Kurtz, and production supervisor Robert Watts. Under the new system, the project met the studio's deadline.[5][112]

Lucas had to write around a scene featuring a human Jabba the Hutt, which was scrapped due to budget and time constraints.[121] Lucas would later claim he wanted to superimpose a stop-motion creature over the actor—which he did with computer-generated imagery (CGI) in the 1997 Special Edition.[122][123] All of the original script drafts describe Jabba as humanoid, with the notion of him being an alien not coming up until work on the 1979 re-release.[124] According to Greedo actor Paul Blake, his own character was created as a result of Lucas having to cut the Jabba scene.[125]

During production, the cast attempted to make Lucas laugh or smile, as he often appeared depressed. At one point, the project became so demanding that Lucas was diagnosed with hypertension and exhaustion and was warned to reduce his stress level.[5][112] Post-production was equally stressful due to increasing pressure from 20th Century-Fox. Moreover, Hamill's car accident left his face visibly scarred, which restricted re-shoots.[112]

Post-production

Star Wars was originally slated for release on Christmas 1976; however, its production delays pushed the film's release to mid-1977.[126] Editor John Jympson began cutting the film together while Lucas was still filming in Tunisia; as Lucas noted, the editor was in an "impossible position" because Lucas had not explained any of the film's material to him. When Lucas watched Jympson's rough cut for the first time, he disliked what he saw. J. W. Rinzler wrote that "Jympson's selection of takes was questionable, and he seemed to be having trouble doing match-cuts." Lucas was prepared to give Jympson more time; Jympson disliked Lucas's working style.[127] As production went on, Lucas still disapproved of Jympson's cut and fired him halfway through the film's production. He commented: "Unfortunately it didn't work out. It's very hard when you are hiring people to know if they are going to mesh with you and if you are going to get what you want. In the end, I don't think he fully understood the movie and what I was trying to do. I shoot in a very peculiar way, in a documentary style, and it takes a lot of hard editing to make it work."[128] After attempting to persuade Jympson to cut the film his way, Lucas replaced him with Paul Hirsch, Richard Chew, and his then-wife, Marcia Lucas, who was also cutting the film New York, New York (1977) with Lucas's friend Martin Scorsese. Richard Chew considered the film to have been cut in a slow, by-the-book manner: scenes were played out in master shots that flowed into close-up coverage. He found that the pace was dictated by the actors instead of the cuts. Hirsch and Chew worked on two reels simultaneously.[5][129]

Jympson's original assembly contained a large amount of footage which differed from the final cut of the film, including several alternate takes and a number of scenes which were subsequently deleted to improve the narrative pace. The most significant material cut was a series of scenes from the first part of the film which introduced Luke Skywalker. These early scenes, set in Anchorhead on the planet Tatooine, presented the audience with Luke's everyday life among his friends as it is affected by the space battle above the planet; they also introduced the character of Biggs Darklighter, Luke's closest friend who departs to join the rebellion.[130] Chew explained the rationale behind removing these scenes as a narrative decision: "In the first five minutes, we were hitting everybody with more information than they could handle. There were too many story lines to keep straight: the robots and the Princess, Vader, Luke. So we simplified it by taking out Luke and Biggs."[131] In an examination of this early cut, which has come to be called the "Lost Cut", David West Reynolds noted the film adopted a "documentary-like" approach that emphasized "clarity, especially in geographic and spatial relationships" over "dramatic or artistic concerns". As a result, the film was more "leisurely paced".[132] Reynolds estimated this early cut contained "30–40%" different footage from the final cut, with most of the differences coming from extended cuts or alternate takes rather than deleted scenes.[132]

After viewing a rough cut, Alan Ladd likened the early Anchorhead scenes to "American Graffiti in outer space". Lucas was looking for a way of accelerating the storytelling, and removing Luke's early scenes would distinguish Star Wars from his earlier teenage drama and "get that American Graffiti feel out of it".[130] Lucas also stated that he wanted to move the narrative focus to C-3PO and R2-D2: "At the time, to have the first half-hour of the film be mainly about robots was a bold idea."[133][134]

Meanwhile, Industrial Light & Magic was struggling to achieve unprecedented special effects. The company had spent half of its budget on four shots that Lucas deemed unacceptable.[112] With hundreds of uncompleted shots remaining, ILM was forced to finish a year's work in six months. Lucas inspired ILM by editing together aerial dogfights from old war films, which enhanced the pacing of the scenes.[5]

Burtt had created a library of sounds that Lucas referred to as an "organic soundtrack". Blaster sounds were a modified recording of a steel cable, under tension, being struck. The lightsaber sound effect was developed by Burtt as a combination of the hum of idling interlock motors in aged movie projectors and interference caused by a television set on a shieldless microphone. Burtt discovered the latter accidentally as he was looking for a buzzing, sparking sound to add to the projector-motor hum.[135] For Chewbacca's growls, Burtt recorded and combined sounds made by dogs, bears, lions, tigers, and walruses to create phrases and sentences. Lucas and Burtt created the robotic voice of R2-D2 by filtering their voices through an electronic synthesizer. Darth Vader's breathing was achieved by Burtt breathing through the mask of a scuba regulator implanted with a microphone,[136] which began the idea of Vader having been a burn-victim, which had not been the case during production.[137]

In February 1977, Lucas screened an early cut of the film for Fox executives, several director friends, along with Roy Thomas and Howard Chaykin of Marvel Comics who were preparing a Star Wars comic book. The cut had a different crawl from the finished version and used Prowse's voice for Darth Vader. It also lacked most special effects; hand-drawn arrows took the place of blaster beams, and when the Millennium Falcon fought TIE fighters, the film cut to footage of World War II dogfights.[138] The reactions of the directors present, such as Brian De Palma, John Milius, and Steven Spielberg, disappointed Lucas. Spielberg, who said he was the only person in the audience to have enjoyed the film, believed that the lack of enthusiasm was due to the absence of finished special effects. Lucas later said that the group was honest and seemed bemused by the film. In contrast, Ladd and the other studio executives loved the film; Gareth Wigan told Lucas: "This is the greatest film I've ever seen" and cried during the screening. Lucas found the experience shocking and rewarding, having never gained any approval from studio executives before.[5] The delays increased the budget from $8 million to $11 million.[139]

With the project $2 million over budget, Lucas was forced to make numerous artistic compromises to complete Star Wars. Ladd reluctantly agreed to release an extra $20,000 funding and in early 1977 second unit filming completed a number of sequences including exterior desert shots for Tatooine in Death Valley and China Lake Acres in California, and exterior Yavin jungle shots in Guatemala, along with additional studio footage to complete the Mos Eisley Cantina sequence.

Soundtrack

On the recommendation of Spielberg, Lucas hired John Williams, who had worked with Spielberg on the film Jaws, for which he won an Academy Award. Lucas originally hired Williams to consult on music editing choices and to compose the source music for the music, telling Williams that he intended to use extant music.[140][141] Lucas believed that the film would portray visually foreign worlds, but that a grand musical score would give the audience an emotional familiarity. Therefore, Lucas assembled his favorite orchestral pieces for the soundtrack, until Williams convinced him that an original score would be unique and more unified, having viewed Lucas's music choices as a temp track. However, a few of Williams's eventual pieces were influenced by the temp track: the "Main Title Theme" was inspired by the theme from the 1942 film Kings Row, scored by Erich Wolfgang Korngold;[142] and the track "Dune Sea of Tatooine" drew from the soundtrack of Bicycle Thieves, scored by Alessandro Cicognini. Lucas would later deny having ever conceived using extant music for the film.[140]

In March 1977, Williams conducted the London Symphony Orchestra to record the Star Wars soundtrack in 12 days.[5] The original soundtrack was released as a double LP in 1977 by 20th Century Records. 20th Century Records also released The Story of Star Wars that year, a narrated audio drama adaptation of the film utilizing some of its original music, dialogue, and sound effects.

The American Film Institute's list of best film scores ranks the Star Wars soundtrack at number one.[143]

Cinematic and literary allusions

.jpg.webp)

According to Lucas, different concepts of the film were inspired by numerous sources, such as Beowulf and King Arthur for the origins of myth and religion.[5] Lucas had originally intended to remake the 1930s Flash Gordon film serials but was unable to obtain the rights; thus, he resorted to drawing from Akira Kurosawa's 1958 film The Hidden Fortress and, allegedly, Joseph Campbell's The Hero with a Thousand Faces.[51][144] Star Wars features many elements derived from Flash Gordon, such as the conflict between rebels and Imperial Forces, the wipes between scenes, the fusion of futuristic technology and traditional mythology, and the famous opening crawl that begins each film.[144][145] The film has also been compared to The Wizard of Oz (1939).[146][147]

The influence of The Hidden Fortress can be seen in the relationship between C-3PO and R2-D2, which evolved from the two bickering peasants, Tahei and Matashichi, and a Japanese family crest seen in the earlier film is similar to the Imperial Crest. Star Wars also borrows heavily from another Kurosawa film, Yojimbo (1961).[144] In both films, several men threaten the hero, bragging about how wanted they are by the authorities, and have an arm being cut off by a blade; Kuwabatake Sanjuro (played by Toshiro Mifune) is offered "twenty-five ryo now, twenty-five when you complete the mission", whereas Han Solo is offered "Two thousand now, plus fifteen when we reach Alderaan." Its sequel Sanjuro (1962) also inspired the hiding-under-the-floor trick featured in the film.[144] Another source of influence was Lawrence of Arabia (1962), which inspired the film's visual approach, including long-lens desert shots. There are also thematic parallels, including the freedom fight by a rebel army against an empire, and politicians who meddle behind the scenes.[144]

Tatooine is similar to the desert planet of Arrakis from Frank Herbert's Dune series. Arrakis is the only known source of a longevity spice; Star Wars makes references to spice in "the spice mines of Kessel", and a spice freighter. Other similarities include those between Princess Leia and Princess Alia, and Jedi mind tricks and "The Voice", a controlling ability used by the Bene Gesserit. In passing, Uncle Owen and Aunt Beru are "moisture farmers"; in Dune, dew collectors are used by Fremen to "provide a small but reliable source of water."[148] Frank Herbert reported that "David Lynch, [director of the 1984 film Dune] had trouble with the fact that Star Wars used up so much of Dune." The pair found "sixteen points of identity" and they calculated that "the odds against coincidence produced a number larger than the number of stars in the universe."[149]

The Death Star assault scene was modeled after the World War II film The Dam Busters (1955), in which Royal Air Force Lancaster bombers fly along heavily defended reservoirs and aim bouncing bombs at dams to cripple the heavy industry of Germany's Ruhr region.[150] Some of the dialogue in The Dam Busters is repeated in the Star Wars climax; Gilbert Taylor also filmed the special effects sequences in The Dam Busters. In addition, the sequence was partially inspired by the climax of the film 633 Squadron (1964), directed by Walter Grauman,[151] in which RAF de Havilland Mosquitos attack a German heavy water plant by flying down a narrow fjord to drop special bombs at a precise point, while avoiding anti-aircraft guns and German fighters. Clips from both films were included in Lucas's temporary dogfight footage version of the sequence.[152] There are also similarities in the Death Star trench sequence to the bridge attack scene in The Bridges at Toko-Ri.[153]

The opening shot of Star Wars, in which a detailed spaceship fills the screen overhead, is a reference to the scene introducing the interplanetary spacecraft Discovery One in Stanley Kubrick's seminal 1968 film 2001: A Space Odyssey. The earlier big-budget science fiction film influenced the look of Star Wars in many other ways, including the use of EVA pods and hexagonal corridors. The Death Star has a docking bay reminiscent of the one on the orbiting space station in 2001.[154] Although golden and male, C-3PO was inspired by the silver female robot Maria, the Maschinenmensch from Fritz Lang's 1927 film Metropolis.[155]

Marketing

While the film was in production, a logo was commissioned from Dan Perri, a title sequence designer who had worked on the titles for films such as The Exorcist (1973) and Taxi Driver (1976). Perri devised a foreshortened STAR WARS logotype consisting of block-capital letters filled with stars and skewed towards a vanishing point. This logo design was originally conceived to follow the same perspective as the film's opening crawl. In the end, Perri's logo was not used for the film's opening title sequence, although it was used widely on pre-release print advertising and on cinema marquees.[156][157]

The logotype eventually selected for on-screen use originated in a promotional brochure that was distributed by Fox to cinema owners in 1976. This brochure was designed by Suzy Rice, a young art director at the Los Angeles advertising agency Seiniger Advertising. On a visit to ILM in Van Nuys, Rice was instructed by Lucas to produce a logo that would intimidate the viewer, and he reportedly asked for the logo to appear "very fascist" in style. Rice's response to her brief was to use an outlined, modified Helvetica Black. After some feedback from Lucas, Rice decided to join the S and T of STAR and the R and S of WARS. Lucas signed off on the brochure in between takes while filming inserts for the Mos Eisley Cantina scene. Gary Kurtz was impressed with Rice's logo and selected it over Perri's design for the film's opening titles, after modifying the letter W to flatten the pointed tips originally designed by Rice. This finalized the design of one of the most recognizable logos in cinema design, although Rice's contribution was not credited in the film.[156]

For the US release in 1977, 20th Century-Fox commissioned a promotional film poster from the advertising agency Smolen, Smith and Connolly. They used the freelance artist Tom Jung who was given the brief of "good over evil." His poster, known as Style ‘A’, depicted Luke Skywalker standing in a heroic pose, brandishing a shining lightsaber above his head, with Princess Leia below him, and a large, ghostly image of Darth Vader's helmet looming behind them. Some Fox executives considered this poster "too dark" and commissioned the Brothers Hildebrandt, a pair of well-known fantasy artists, to rework the poster for the UK release. When the film opened in British theaters, the Hildebrandts' Style ‘B’ poster was used in cinema billboards. Fox and Lucasfilm subsequently decided that they wanted to promote the new film with a less stylized and more realistic depiction of the lead characters. Producer Gary Kurtz turned to the film poster artist Tom Chantrell, who was already well known for his prolific work for Hammer horror films, and commissioned a new version. Two months after Star Wars opened, the Hildebrandts' poster was replaced by Chantrell's Style ‘C’ poster in UK cinemas.[158][159][160][161]

Charles Lippincott was the marketing director for Star Wars. As 20th Century-Fox gave little support for marketing beyond licensing T-shirts and posters, Lippincott was forced to look elsewhere. He secured deals with Marvel Comics for a comic book adaptation, and with Del Rey Books for a novelization. A fan of science fiction, he used his contacts to promote the film at the San Diego Comic-Con and elsewhere within science-fiction fandom.[5][65]

Release

First public screening

On May 1, 1977, the first public screening was held at Northpoint Theatre[162][163] in San Francisco, where American Graffiti was test-screened, four years earlier.[164][165]

Premiere and initial release

Worried that Star Wars would be beaten out by other summer films, such as Smokey and the Bandit, 20th Century-Fox moved the release date to May 25, the Wednesday before Memorial Day. However, only 37 theaters ordered the film to be shown in North America. In response, the studio demanded that theaters order Star Wars if they wanted the eagerly anticipated The Other Side of Midnight based on Sidney Sheldon's 1973 novel by the same name.[5]

Star Wars debuted on Wednesday, May 25, 1977, in fewer than 32 theaters, and eight more on Thursday and Friday. Kurtz said in 2002, "That would be laughable today." It immediately broke box office records, effectively becoming one of the first blockbuster films, and Fox accelerated plans to broaden its release.[65][166] Lucas himself was not able to predict how successful Star Wars would be. After visiting the set of the Steven Spielberg film Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Lucas was sure Close Encounters would outperform the yet-to-be-released Star Wars at the box office. Spielberg disagreed, and believed Star Wars would be the bigger hit. Lucas proposed they trade 2.5% of the profit on each other's films; Spielberg took the trade, and still receives 2.5% of the profits from Star Wars.[167]

Amidst Fox pessimism, Lucas elected to forgo his option to an extra $500,000 fee for directing Star Wars, in exchange for obtaining the merchandising and sequel rights for the movie from Fox.[168] The Other Side of Midnight was supposed to be the studio's big summer hit, while Lucas's movie was considered the "B track" for theater owners nationwide. While Fox requested Mann's Chinese Theatre, the studio promised that the film needed only two weeks.[169] Fearing that the film would fail, Lucas had made plans to be in Hawaii with his wife Marcia. Having forgotten that the film would open that day,[170] he spent most of Wednesday in a sound studio in Los Angeles. When Lucas went out for lunch with Marcia, they encountered a long line of people along the sidewalks leading to Mann's Chinese Theatre, waiting to see Star Wars.[112] He was still skeptical of the film's success, even with enthusiastic reports from Ladd and the studio. While in Hawaii, it was not until he watched Walter Cronkite discuss the gigantic crowds for Star Wars on CBS Evening News that Lucas realized he had become very wealthy. Francis Ford Coppola, who needed money to finish Apocalypse Now, sent a telegram to Lucas's hotel asking for funding.[170] Even technical crew members, such as model makers, were asked for autographs, and cast members became instant household names;[5] when Ford visited a record store to buy an album, enthusiastic fans tore half his shirt off.[170]

On opening day I ... did a radio call-in show ... this caller, was really enthusiastic and talking about the movie in really deep detail. I said, 'You know a lot about the film.' He said, 'Yeah, yeah, I've seen it four times already.'

—Producer Gary Kurtz, on when he realized Star Wars had become a cultural phenomenon[171]

The film was a huge success for 20th Century-Fox, and was credited for reinvigorating the company. Within three weeks of the film's release, the studio's stock price had doubled to a record high. Prior to 1977, 20th Century-Fox's greatest annual profits were $37 million, while in 1977, the company broke that record by posting a profit of $79 million.[5]

Although the film's cultural neutrality helped it to gain international success, Ladd became anxious during the premiere in Japan. After the screening, the audience was silent, leading him to fear that the film would be unsuccessful. Ladd was reassured by his local contacts that this was a positive reaction considering that in Japan, silence was the greatest honor to a film, and the subsequent strong box office returns confirmed its popularity.[5]

After two weeks William Friedkin's Sorcerer replaced Star Wars at Mann's Chinese Theatre because of contractual obligations; Mann Theatres moved the film to a less-prestigious location after quickly renovating it.[169] When Star Wars made an unprecedented second opening at Mann's Chinese Theatre on August 3, 1977, after Sorcerer failed, thousands of people attended a ceremony in which C-3PO, R2-D2 and Darth Vader placed their footprints in the theater's forecourt.[166][5] At that time Star Wars was playing in 1,096 theaters in the United States.[172] Approximately 60 theaters played the film continuously for over a year;[173] in 1978, Lucasfilm distributed "Birthday Cake" posters to those theaters for special events on May 25, the one-year anniversary of the film's release.[174] Star Wars premiered in the UK on December 27, 1977. News reports of the film's popularity in America caused long lines to form at the two London theaters that first offered the film; it became available in 12 large cities in January 1978, and other London theaters in February.[175]

Box office

Star Wars remains one of the most financially successful films of all time. The film opened on a Wednesday in 32 theaters expanding to 43 screens on the Friday and earning $2,556,418 in its first six days to the end of the Memorial Day weekend[176] ($12.3 million in 2022 dollars). Per Variety's weekly box office charts, the film was number one at the US box office for its first three weeks. It was replaced by The Deep but gradually added screens and returned to number one in its seventh week, building up to $7 million weekends as it entered wide release ($33.8 million in 2022 dollars)[3] and remained number one for the next 15 weeks. It replaced Jaws as the highest-earning film in North America just six months into release,[177] eventually earning over $220 million during its initial theatrical run ($1.06 billion in 2022 dollars).[178] Star Wars entered international release towards the end of the year, and in 1978 added the worldwide record to its domestic one,[179] earning $410 million in total.[180] Its biggest international market was Japan, where it grossed $58.4 million.[181]

On July 21, 1978, while still in current release in 38 theaters in the U.S., the film expanded into a 1,744 theater national saturation windup of release and set a new U.S. weekend record of $10,202,726.[182][183][184] The gross prior to the expansion was $221,280,994. The expansion added a further $43,774,911 to take its gross to $265,055,905. Reissues in 1979 ($22,455,262), 1981 ($17,247,363), and 1982 ($17,981,612) brought its cumulative gross in the U.S. and Canada to $323 million,[185][186] and extended its global earnings to $530 million.[187] In doing so, it became the first film to gross $500 million worldwide,[188] and remained the highest-grossing film of all time until E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial broke that record in 1983.[189]

The release of the Special Edition in 1997 was the highest-grossing reissue of all-time with a gross of $138.3 million, bringing its total gross in the United States and Canada to $460,998,007, reclaiming the all-time number one spot.[190][3][191][192] Internationally, the reissue grossed $117.2 million, with $26 million from the United Kingdom and $15 million from Japan.[181] In total, the film has grossed over $775 million worldwide.[3]

Adjusted for inflation, it had earned over $2.5 billion worldwide at 2011 prices,[193] which saw it ranked as the third-highest-grossing film at the time, according to Guinness World Records.[194] At the North American box office, it ranks second behind Gone with the Wind on the inflation-adjusted list.[195]

Reception

Critical response

What makes the Star Wars experience unique, though, is that it happens on such an innocent and often funny level. It's usually violence that draws me so deeply into a movie—violence ranging from the psychological torment of a Bergman character to the mindless crunch of a shark's jaws. Maybe movies that scare us find the most direct route to our imaginations. But there's hardly any violence at all in Star Wars (and even then it's presented as essentially bloodless swashbuckling). Instead, there's entertainment so direct and simple that all of the complications of the modern movie seem to vaporize.

—Roger Ebert, in his review for the Chicago Sun-Times[196]

Star Wars received critical acclaim. In his 1977 review, Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times called the film "an out-of-body experience", compared its special effects to those of 2001: A Space Odyssey, and opined that the true strength of the film was its "pure narrative".[196] Vincent Canby of The New York Times called the film "the movie that's going to entertain a lot of contemporary folk who have a soft spot for the virtually ritualized manners of comic-book adventure" and "the most elaborate, most expensive, most beautiful movie serial ever made".[197] A.D. Murphy of Variety described the film as "magnificent" and said George Lucas had succeeded in his attempt to create the "biggest possible adventure fantasy" based on the serials and older action epics from his childhood.[198] Writing for The Washington Post, Gary Arnold gave the film a positive review, writing that the film "is a new classic in a rousing movie tradition: a space swashbuckler."[199] However, the film was not without its detractors: Pauline Kael of The New Yorker criticized Star Wars, stating that "there's no breather in the picture, no lyricism", and that it had no "emotional grip".[200] John Simon of New York magazine also panned the film and wrote, "Strip Star Wars of its often striking images and its highfalutin scientific jargon, and you get a story, characters, and dialogue of overwhelming banality."[201] Stanley Kauffmann, reviewing the film in The New Republic, opined that it "was made for those (particularly males) who carry a portable shrine within them of their adolescence, a chalice of a Self that was Better Then, before the world's affairs or—in any complex way—sex intruded."[202]

When Star Wars opened in the UK, Derek Malcolm of The Guardian concluded that it "plays enough games to satisfy the most sophisticated", though he stated that Lucas's earlier films were better.[203] Barry Norman of Film... called the movie "family entertainment at its most sublime", which "combines all the best-loved themes of romantic adventure", with a script evoking "everyone's glorious memories of Saturday matinees".[204] The Daily Telegraph's science correspondent Adrian Berry said that Star Wars "is the best such film since 2001 and in certain respects it is one of the most exciting ever made". He described the plot as "unpretentious and pleasantly devoid of any 'message'."[205] A few critics found fault in the film's lack of representation of African Americans.[lower-alpha 3][lower-alpha 4] Lucas was taken aback by some of the criticisms, while Lippincott stated, "We have barely dug into this galaxy and what it's like."[209]

Gene Siskel, writing for the Chicago Tribune in 1977, said, "What places it a sizable cut above the routine is its spectacular visual effects, the best since Stanley Kubrick's 2001."[210][211] Andrew Collins of Empire magazine awarded the film five out of five and said, "Star Wars' timeless appeal lies in its easily identified, universal archetypes—goodies to root for, baddies to boo, a princess to be rescued and so on—and if it is most obviously dated to the 70s by the special effects, so be it."[212] In his 1977 review, Robert Hatch of The Nation called the film "an outrageously successful, what will be called a 'classic,' compilation of nonsense, largely derived but thoroughly reconditioned. I doubt that anyone will ever match it, though the imitations must already be on the drawing boards."[213] In a more critical review, Jonathan Rosenbaum of the Chicago Reader stated, "None of these characters has any depth, and they're all treated like the fanciful props and settings."[214] Peter Keough of the Boston Phoenix said, "Star Wars is a junkyard of cinematic gimcracks not unlike the Jawas' heap of purloined, discarded, barely functioning droids."[215]

The film continues to receive critical acclaim from modern critics. On the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, 93% of 137 critics' reviews are positive, with an average rating of 8.8/10. The website's consensus reads: "A legendarily expansive and ambitious start to the sci-fi saga, George Lucas opened our eyes to the possibilities of blockbuster filmmaking and things have never been the same."[216] Metacritic, which uses a weighted average, assigned the film a score of 90 out of 100, based on 24 critics, indicating "universal acclaim".[217] In his 1997 review of the film's 20th anniversary release, Michael Wilmington of the Chicago Tribune gave the film four out of four stars, saying, "A grandiose and violent epic with a simple and whimsical heart."[218] A San Francisco Chronicle staff member described the film as "a thrilling experience".[219] In 2001 Matt Ford of the BBC awarded the film five out of five stars and wrote, "Star Wars isn't the best film ever made, but it is universally loved."[220] CinemaScore reported that audiences for Star Wars's 1999 re-release gave the film a "A+" grade.[221]

Accolades