Speedwell Island

Speedwell Island (formerly Eagle Island; Spanish Isla Águila) is one of the Falkland Islands, lying in the Falkland Sound, southwest of Lafonia, East Falkland.

Isla Águila | |

|---|---|

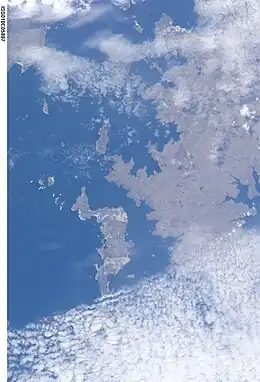

Satellite photo with Speedwell Island just below and to left of center | |

Speedwell Island | |

| Geography | |

| Location | Atlantic Ocean |

| Coordinates | 52°13′10″S 59°43′00″W |

| Archipelago | Speedwell Island group |

| Area | 51.5 km2 (19.9 sq mi) |

| Length | 17.5 km (10.87 mi) |

| Width | 5 km (3.1 mi) |

| Administration | |

Falkland Islands | |

The island has an area of 51.5 km2 (19.9 sq mi), measuring approximately 17.5 km (10.9 mi) from north to south and 5 km (3.1 mi) across at its widest central part. It is generally low-lying with some permanent ponds. It is separated from Lafonia by the Eagle Passage, which retains Speedwell Island's former name. It is the largest of the Speedwell Island group, which includes the Elephant Cays, George Island, Barren Island, and Annie Island.[1]

Ecology

One of the largest rodent-free islands in the Falklands, Speedwell Island has a thriving population of native songbirds, seabirds, and penguins. In total, more than 40 species of birds have been recorded on the island. The breeding colony of South American sea lions in Speedwell Pass produces about 90 pups annually, and the animals haul out on most of the group's islands, including Speedwell Island itself. The island has also been operated as a sheep farm for more than a century, leading to serious soil erosion in coastal areas due to overgrazing.

History

Isabella

On 8 February 1813 the Isabella, a British ship of 193 tons en route from Sydney to London, ran aground off the coast of Speedwell Island, then known as Eagle Island. Among the ship's 54 passengers and crew, all of whom survived the wreck, was the United Irish general and exile Joseph Holt, who subsequently detailed the ordeal in his memoirs.[2] Also aboard had been the heavily pregnant Joanna Durie, who on 21 Feb 1813 gave birth to Elizabeth Providence Durie.

The next day, 22 February 1813, six men who had volunteered to seek help from any nearby Spanish outposts that they could find set out in one of the Isabella's longboats. Braving the South Atlantic in a boat little more than 17 ft long (5.2 m), they made landfall on the mainland at the River Plate just over a month later. The British gun brig HMS Nancy under the command of Lieutenant William D'Aranda was sent to rescue the survivors.

On 5 April Captain Charles Barnard of the American sealer Nanina was sailing off the shore of Speedwell Island, with a discovery boat deployed looking for seals. Having seen smoke and heard gunshots the previous day, he was alert to the possibility of survivors of a ship wreck. This suspicion was heightened when the crew of the boat came aboard and informed Barnard that they had come across a new moccasin as well as the partially butchered remains of a seal. At dinner that evening, the crew observed a man approaching the ship who was shortly joined by eight to ten others. Both Barnard and the survivors from the Isabella had harboured concerns the other party was Spanish and were relieved to discover their respective nationalities.

Barnard dined with the Isabella survivors that evening and finding that the British party were unaware of the War of 1812 informed the survivors that technically they were at war with each other. Nevertheless, Barnard promised to rescue the British party and set about preparations for the voyage to the River Plate. Realising that they had insufficient stores for the voyage he set about hunting wild pigs and otherwise acquiring additional food. While Barnard was gathering supplies, however, the British took the opportunity to seize the Nanina and departed leaving Barnard, along with one member of his own crew and three from the Isabella, marooned. Shortly thereafter, the Nancy arrived from the River Plate and encountered the Nanina, whereupon Lieutenant D'Aranda rescued the erstwhile survivors of the Isabella and took the Nanina itself as a prize of war.

Barnard and his party survived for eighteen months marooned on the islands until the British whalers Indispensable and Asp rescued them in November 1814. The British admiral in Rio de Janeiro had requested their masters to divert to the area to search for the American crew. In 1829, Barnard published an account of his survival entitled A Narrative of the Sufferings and Adventures of Capt Charles H. Barnard.[3]

Later history

The 1837 survey of the Falkland Islands by HMS Sparrow under the command of Lieutenant Robert Lowcay noted that there were wild pigs on the island.

In 1929 Alexander Dugas, a Frenchman employed on Sealion Island, committed suicide, and his companions felt it necessary to inform the authorities. The lack of a harbour on Sealion Island meant, however, that no boat of any size could be kept on the island, and so a determined individual named Benny Davis constructed a makeshift craft from wooden barrels and launched it into the surf. Davis set out just before dark, and reached Speedwell Island, almost 30 miles distant, some twelve hours later. He explained that he had simply headed west until he could smell the cormorants on nearby Annie Island.[4]

Important Bird Area

The Speedwell Island group (excluding the Elephant Cays, which form a separate IBA) has been identified by BirdLife International as an Important Bird Area. Birds for which the site is of conservation significance include blackish cinclodes, Cobb's wrens, dolphin gulls (500 breeding pairs), Falkland steamer ducks (600 pairs), Magellanic penguins (10,000 pairs), ruddy-headed geese, sooty shearwaters, southern giant petrels (1,000 pairs), striated caracaras, and white-bridled finches.[1]

References

- "Speedwell Island Group". Important Bird Areas factsheet. BirdLife International. 2019. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

- Holt, Joseph (1838). Croker, Thomas Crofton (ed.). Memoirs of Joseph Holt, general of the Irish rebels, in 1798. Vol. II. London: Henry Colburn. pp. 323–375.

- Barnard, Charles H. (1836) [1829]. A narrative of the sufferings and adventures of Capt. Charles H. Barnard. New York: J.P. Callender.

- Wagstaff, William (2001). Falkland Islands: The Bradt Travel Guide (1st ed.). Bradt Travel Guides. p. 125. ISBN 1-84162-037-8.

- Bateson, Charles (1972). Australian Shipwrecks - Vol 1 1622-1850. Vol. I. Sydney: AH & AW Reed. ISBN 0-589-07112-2.

- Southby-Tailyour, Ewen (1985). Falkland Islands Shores. Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-341-9.

- Stonehouse, Bernard, ed. (2002). Encyclopedia of Antarctica and the Southern Oceans. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-98665-8.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)

External links

- Satellite picture at the Wayback Machine (archived December 23, 2010)