South Puget Sound

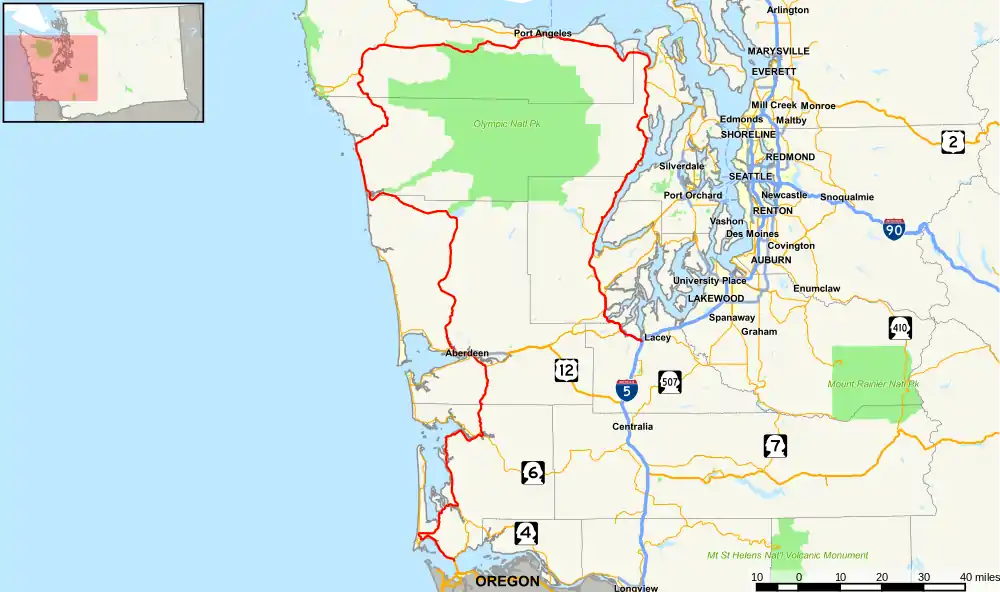

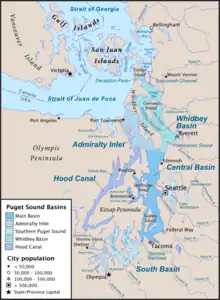

South Puget Sound is the southern reaches of Puget Sound in Southwest Washington, in the United States' Pacific Northwest. It is one of five major basins encompassing the entire Sound, and the shallowest basin, with a mean depth of 37 meters (121 ft).[1][2] Exact definitions of the region vary:[lower-alpha 1] the state's Department of Fish and Wildlife counts all of Puget Sound south of the Tacoma Narrows for fishing regulatory purposes.[4] The same agency counts Mason, Jefferson, Kitsap, Pierce and Thurston Counties for wildlife management.[5] The state's Department of Ecology defines a similar area south of Colvos Passage.[lower-alpha 2]

The term "South Sound Region" or just "South Sound" is used to apply to the communities surrounding the water.[lower-alpha 3] The South Sound contains the Olympia-Tumwater Metropolitan Statistical Area and the Shelton Micropolitan Statistical Area.[8] The terms appear in names of local institutions and commercial entities such as South Puget Sound Community College in Olympia and South Sound Center in Lacey.

Human history

Archaeology indicates that continuous human occupation began approximately ten thousand years ago by the Salish peoples who still live there.[9][10] Lieutenant Peter Puget perhaps made first contact with the indigenous peoples and first charted the South Sound in the 1790s, giving rise to the original "Puget's Sound", which was then just the area south of the Narrows.[11] Fort Nisqually was established in 1832, and Fort Steilacoom became the territorial militia headquarters in August 1849.[12] Both preceded by decades Fort Lewis (now Joint Base Lewis-McChord), which was created for World War I. The Medicine Creek Treaty between the tribes and the United States was signed in 1854 at the Nisqually River delta in the South Sound area, when settlers from other parts of America began to arrive.

Olympia became a settlement in the 1840s, providing access to inland areas in Southwest Washington.[13] Tumwater pioneers Michael Simmons, born in Kentucky, and George Washington Bush, a multiracial War of 1812 veteran from Pennsylvania, were among the first Puget Sound settlers from the United States in 1844. Simmons and Bush likely hacked a path through virgin forest from the Oregon Trail. In 1860 the route was made into a military road between Fort Vancouver on the Columbia to Forts Nisqually and Steilacoom on the Sound.[14][15]

The Indian Shaker Church was founded in 1881 at Mud Bay by Native Americans "Mud Bay" Sam Yowaluch and "Mud Bay" Louie Yowaluch, and John Slocum of the Squaxin Island Tribe.[16][17] The church spread throughout the Northwest United States and Southern British Columbia in the 19th century, and still exists as of 2017.

The 20th century was characterized by rapid development and urbanization on the shores of the South Sound.

Geography

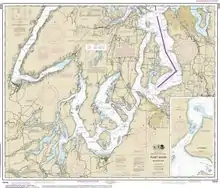

The passages and inlets west of Hartstene Island, due to extensive Pleistocene glaciation, contain the shallowest water of the entire Sound.[18] Away from the Tacoma Narrows, the basin has low rates of tidal exchange (tidal flushing), leading to issues with eutrophication.[19][20] Shoreline complexity is greater in the South Sound than in the other basins, due to the many passages, inlets and islands:[11]

- Passages

- Pickering Passage

- Peale Passage

- Dana Passage

- Squaxin Passage

- Inlets

- Hammersley Inlet and Oakland Bay

- Totten Inlet

- Skookum Inlet

- Eld Inlet

- Budd Inlet

- Henderson Inlet

- Case Inlet

- Islands

Mudflats

Great tidal variation gives rise to extensive mudflats in the inlets of the South Sound.[lower-alpha 4] Tidal variation increases with distance from the entrance to Puget Sound and is greatest at 15+ feet in the South Sound, versus only 11 in Seattle (compare 5 in Los Angeles).[21] Mudflats include the Mud Bay region at the southern end of Eld Inlet and Oyster Bay at the southern end of Totten Inlet. The entirety of Oyster Bay is exposed mud at low tide.[22]

Watersheds

Major watersheds in the South Sound include the Deschutes River (Washington) and the Nisqually River.[23]

Microclimate

The Chehalis Gap brings Pacific moist air to the entire Puget Sound area, arriving first in the South Sound (the gap near Matlock is 15 miles (24 km) from Shelton on Oakland Bay). Olympia is wetter than Seattle due to the absence of protection from the Olympic Mountains, and has been reckoned the rainiest city in America with 64 days of rain a year.[24]

Aquaculture

Aquaculture in the South Sound produces much of the state's commercial shellfish harvest.[20] Oyster farming in Totten Inlet and its side branch, Little Skookum, produce the best known edible oysters in the South Puget Sound.[25] Geoduck production leads the nation.[lower-alpha 5]

Governments

Jurisdictions in the South Sound include the state government and subordinate counties and cities; Nisqually, Squaxin Island, and Puyallup Tribes;[23] and the federal government which is a landowner and operator of Joint Base Lewis-McChord.

Transportation

Transportation by water was once common in the South Sound. Ferries once linked many locations such as Steilacoom.[27] The Steilacoom-Anderson Island Ferry provides service between Steilacoom and South Sound islands using two vessels.[28] The north end of the South Sound region has the only cross-Sound bridge, the Tacoma Narrows Bridge (technically two adjacent bridges since 2007).[29][30] Interstate 5 and U.S. 101 form a semicircular pathway from Shelton to Tacoma around the South Sound, and Washington State Route 3 runs up from Shelton through the center of the Kitsap Peninsula. State Route 16 across the Narrows Bridge completes a loop around the South Sound. Dead end county roads traverse the length of the southernmost peninsulas in the Totten Inlet-Eld Inlet-Budd Inlet area: Kamilche Point Road, Steamboat Island Road, Cooper Point Road, Libby Road, and Johnson Point Road.[31]

The Port of Olympia is a deepwater port for oceangoing vessels. It is sustained by dredging in Budd Inlet and Capitol Lake,[32] an impoundment of the Deschutes River. Without dredging, the Deschutes would recreate its historical estuary with annual 35,000 cubic yards (27,000 m3) of sediment deposit.[lower-alpha 6][34]

Tacoma Rail, BNSF Railway, Union Pacific Railroad support general rail freight,[35] and a little-used, 48-mile (77 km) Puget Sound and Pacific Railroad spur to the Kitsap Peninsula exists. Historically, logging railroads such as Mud Bay Logging Company were common on the South Sound shores and inland; these have been abandoned.[36]

Sanderson Field in Shelton and Olympia Regional Airport are the only major public airports (see List of airports in Washington). Large military airfields exist onboard Joint Base Lewis-McChord.

Marine mammals

Gray and humpback whales are rare in the South Sound but have been known to come there to feed and perhaps shelter whale calves.[37][38] Southern resident killer whales (orcas) have been reported as far south as Eld Inlet.[39] Smaller species include Dall's porpoise (Phocoenoides Dalli), harbor seals (Phoca Vitulina) and the Pacific harbor porpoise (Phocoena phocoena).[40] A single sea otter was sighted in the South Sound in 2012.[41]

Footnotes

- Neither is there agreement on the boundaries of Puget Sound itself between scientists, geographers and lawmakers.[3]

- "The South Puget Sound planning area is made up of numerous inlets and bays extending from Colvos Passage to Totten Inlet. The South Puget Sound area includes Case Inlet, Budd Inlet, Ed Inlet, Carr Inlet, Hammersly Inlet, Henderson Inlet and several other small areas. Oakland Bay, Pickering Passage, Hale Passage, Peale Passage, Dana Passage, Drayton Passage, Balch Passage, Nisqually Reach and North Bay are also covered." (Washington Department of Ecology[6])

- "Thurston County is located on the southern end of Puget Sound in Western Washington, referred to as the South Sound." (Washington Employment Security Department[7])

- "Mudflats are common along the Nisqually River delta, in the shallow headwaters at the north ends of Case and Carr inlets, and extensively in the heads of the small inlets at the southwest."[18]

- A single Mason County producer contributes 700,000 pounds (320,000 kg), or nearly half of the 1,600,000-pound (730,000 kg) national geoduck harvest.[26]

- "Since 1951, only minimal sediment amounts have entered Budd Inlet as a result of the dam. These maritime industries [Port of Olympia, yacht club and marina] do not need to dredge as often as they once did." (Dani Madrone, Deschutes Estuary Restoration Team[33])

References

Notes

- Burns 1985, p. 67.

- Gustafson et al. 2000.

- "Geographic boundaries of Puget Sound and the Salish Sea", Encyclopedia of Puget Sound, University of Washington, 2015

-

Marine Area 13: South Puget Sound, Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife,

Marine Area 13 (South Puget Sound) encompasses all waters south of the Tacoma Narrows Bridge.

- South Puget Sound Wildlife Area, Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife

- South Puget Sound Geographic Response Plan, Washington Department of Ecology, 2003

- Thurston County profile, Washington Employment Security Department, February 2016

- OMB statistical areas maps (PDF), Washington State Office of Financial Management, August 23, 2016

- Puget Salish People of Washington (PDF), Educational Resources for Washington State Teachers, Seattle: Northwest Heritage Resources, p. 2

- Robin K. Wright (January 16, 2014), "Historical Coast Salish art", official blog, Seattle: Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture

- Burns 1985, p. 66.

- The Official History of the Washington National Guard, Washington Military Department

- WPA Guide 1941, p. 179.

- Phelps 1978.

- Prosch 1908.

- Washington Secretary of State 1996, p. 3.

- David Wilma (September 4, 2000), "Native Americans organize the Indian Shaker Church in 1892", HistoryLink, Seattle: History Ink

- Burns 1985, p. 69.

- Summary of South Puget Sound Water Quality Study, Washington Department of Ecology, September 2002, Pub 02-03-020

- John Dodge, Profiles of South Sound inlets and watersheds (PDF), The Olympian

- Kruckeberg 1991, p. 69.

- Mueller & Mueller 2006, p. 258.

- The 2014/2015 Action Agenda for Puget Sound: South Puget Sound (PDF) (watersheds map), Puget Sound Partnership, 2014

- "Is Seattle the rainiest city in the U.S.?". 19 August 2015.

- Rowan Jacobsen (29 August 2007). "Hood Canal and Southern Puget Sound: Totten Inlet". The Oyster Guide. Retrieved 2017-03-03.

- Andy Hobbs (June 11, 2016), "Neighbors fight geoduck farm in Washington's shellfish heartland", The Olympian

- Mueller & Mueller 2006, p. 18.

- "Pierce County's Ferry fleet". Pierce County, Washington. Archived from the original on 2007-09-28.

- Brian Zylstra (April 11, 2012), "Cross-sound bridge plans", From Our Corner (official blog), Washington Secretary of State

- Beekman, Dan; Santos, Melissa (July 16, 2007), "First traffic crosses new bridge", The News Tribune, Tacoma

- DeLorme 2002, pp. 62–63.

- Moffatt and Nichol (March 27, 2009), Capitol Lake alternatives analysis–Dredging and disposal addendum (PDF)

- Dani Madrone (2014), "What stands in the way of Deschutes estuary restoration? (Besides a dam, of course...)" (PDF), Summer newsletter, Deschutes Estuary Restoration Team

- John Dodge (May 30, 2009), "Estuary or lake?", The Olympian

- Pierce-Lewis-Thurston County rail map, Tacoma Rail, retrieved 2017-03-03

- Hannum 2002.

- Gray whale spotted in backwater of south Puget Sound, Seattle: KOMO-TV, June 19, 2013

- More humpback whales visit waters off Washington state, Associated Press, June 15, 2013 – via The Oregonian (Portland)

- Natalie DeFord, "Orcas in Thurston County's Eld Inlet getting hassled by boaters", The Olympian

- Grette Associates 2009, p. 65.

- "Sea Otter (Enhydra lutris)", Encyclopedia of Puget Sound, University of Washington, 2013. Originally published by Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife as Threatened and Endangered Wildlife in Washington: 2012 Annual Report.

Sources

- Burns, Robert (1985), The Shape & Form of Puget Sound, University of Washington Press, ISBN 0295961848

- Washington Atlas and Gazetteer (sixth ed.), DeLorme, 2002, ISBN 0-89933-329-X

- Federal Writers' Project (1941), The WPA Guide to Washington: The Evergreen State, American Guide Series, ISBN 9781595342454

- Grette Associates (July 14, 2009), Thurston County Shoreline Master Program Update: Shoreline Analysis and Characterization (PDF), Thurston County, Washington

- Gustafson, Richard G.; Lenarz, William H.; McCain, Bruce B.; Schmitt, Cyreis C.; Grant, W. Stewart; Builder, Tonya L.; Methot, Richard D. (November 2000), "Environmental history and features of Puget Sound", Status Review of Pacific Hake, Pacific Cod, and Walleye Pollock from Puget Sound, Washington, National Marine Fisheries Service, NMFS-NWFSC-44,

Puget Sound is a fjord-like estuary located in northwest Washington state and covers an area of about 2,330 km2, including 3,700 km of coastline. It is subdivided into five basins or regions: 1) North Puget Sound, 2) Main Basin, 3) Whidbey Basin, 4) South Puget Sound, and 5) Hood Canal

(entire document at https://www.nwfsc.noaa.gov/publications/scipubs/techmemos/tm44/tm44.htm) - Hannum, James (2002), Gone but not forgotten : abandoned railroads of Thurston County, Washington, Olympia, Wash: Hannum House Publications, ISBN 0-9679043-2-3

- Kruckeberg, Arthur R. (1991), The Natural History of Puget Sound Country, University of Washington Press, ISBN 9780295970196

- Mueller, Marge; Mueller, Ted (2006), Afoot and Afloat: South Puget Sound and Hood Canal, The Mountaineers Books, ISBN 9780898869521

- Phelps, Myra L. (1978), Public Works in Seattle: a Narrative History, the Engineering Department, 1875-1975, Seattle Engineering Department

- Prosch, Thomas W. (January 1, 1908), "The Military Roads of Washington Territory", The Washington Historical Quarterly

- "Washington churches" (PDF), Indian Shaker Church of Washington, Records, Washington Secretary of State, c. 1996, pp. 16–17, Ms 29