Songhai people

The Songhai people (also Ayneha, Songhay or Sonrai) are an ethnolinguistic group in West Africa who speak the various Songhai languages. Their history and lingua franca are linked to the Songhai Empire, which dominated the western Sahel in the 15th and 16th centuries. Predominantly a Muslim community, the Songhai are found primarily throughout Niger and Mali in the Western sudanic region (not the country). The name Songhai was historically neither an ethnic nor linguistic designation, but a name for the ruling caste of the Songhay Empire, which are the Songhai proper of sunni and Askya dynasty found predominantly in present-Niger.[4] However, the correct term used to refer to this group of people collectively by the natives is "Ayneha".[5][6] Although some Speakers in Mali have also adopted the name Songhay as an ethnic designation,[7] other Songhay-speaking groups identify themselves by other ethnic terms such as Zarma (or Djerma, the largest subgroup) or Isawaghen. The dialect of Koyraboro Senni spoken in Gao is unintelligible to speakers of the Zarma dialect of Niger, according to at least one report.[8] The Songhay languages are commonly taken to be Nilo-Saharan, but this classification remains controversial. Nicolai considers the Songhay languages as an Afroasiatic Berber subgroup or a new subgroup of Semitic languages restructured under Mande and Nilo-Saharan influence, the lexicon of Songhay languages includes many completes lexical fields close to Berbers languages, old and new Semitic, Northern Songhay speakers are Berbers from Tuareg people : Dimmendaal (2008) believes that for now it is best considered an independent language family.[9]

A songhay woman in festival. | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| c. 8.4 million | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| West Africa | |

| 5,106,423 (21.2%)[1] | |

| 1,984,114 (5.9%)[2] | |

| 406,000 (2.9%)[3] | |

| Languages | |

| Songhay languages | |

| Religion | |

| Islam | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Igdalen, Ingalkoyyu, Arma, Belbali, Maouri, Idaksahak | |

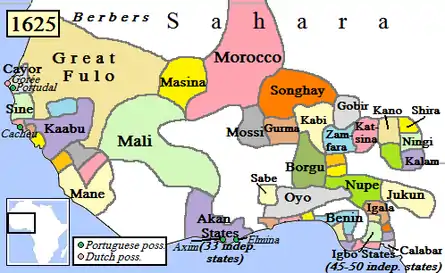

The Songhai are a Nilo-Saharan Muslim population established between the Sahel and the Sahara. Having a long military tradition, they established great empires and kingdoms including the Gao Empire, the African largest contiguous land Empire of Songhai, the Dendi kingdom, the Zabarma Emirate and the Maraba kingdom during the Zabarma invasions in Gurunsi land ( Burkina Faso, Ghana) and in Southern Senufo land (Ivory Coast).

The Songhai Empire expanded by conquering vast densely populated territories and empires such as the Mali Empire, the former territories of the Ghana Empire, the Hausaland, the Empire of Great Fulo and the Mossi Empire.

They are divided into two large groups, the Southern Songhai living along the Niger River are founders of great empires. The Northern Songhai made up of Nomadic pastoralists and inhabitants of the oases living in the Sahara. A third group, the Zabarmawi, born from centuries of travel to Mecca is formed in Sudan.

The Songhai are the inhabitants of the historic cities of Timbuktu, Djenné, Gao and are the majority of the population of Niamey, the capital of Niger.

The Songhay personalities who have had a great impact on history are the emperors Sunni Ali, Askia Muhammad I and the scholars Ahmad Baba al-Timbukti, Mahmud Kati authors of Tarikh al-Fattash and abd Al Rahman al sa'adi author of Tarikh al-Sudan.

Etymology and Names

The word Songhai comes from the terms Song and hay, Song is the name of the Proto-Songhay and hay is used to designate a country, a nation. Song-hay therefore means 'the nation of the Song', 'the country of the Song' or 'the multitude of the Song'. The term Songhai does not designate the ethnic group but the country of the ethnic group, the nation of the song. The Songhai use the term 'ayneha: I said that' to refer to their people and each identifies with his sub-group.[10]

The term zaghay is an oriental pronunciation of the word Songhai and the terms kagho and al kawkaw refer to Gao-Saney, the capital of Gao Empire and to people of Gao.

The Kwarezmian Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi is the first to mention Al-kawkaw in his chronicles in the 9th Century.[11]In the year 872, in his Tarikh, the writer Al yaqubi of the Abbasid Caliphate speaks of al kaw kaw as the most powerful kingdom in the Bilad al-Sudan. The other ancient writers who spoke of the Songhai country in their writings are the Persians Ibn al-Faqih (year 973) in his mukhtasar kitab al-buldan,[12] the Arab abassid Ibn Hawqal (988),[13] al muhalabbi, the Byzantine Muslim Yaqut al-Hamawi, the Andalusian Arab Al Bakri (1068) in his Book kitāb al-Masālik wa'l Mamālik and the Arab Al idrisi (1154).

Zaghay also refers to the prestigious Za Dynasty of the Gao Empire which reigned at the time of most of these writers and zaghay can be defined as The nation of the za, The country of the za. The name that the Hausa make of Songhai is ' Zaberma|zabarma' in reference to the za dynasty and the Zarma subgroup, it also means country and its inhabitants the Songhai are called Zabarmawa (the inhabitants of Zabarma), this name takes more of importance with the Zabarma Emirate. Zabarmawi is the name that the Arabs give to songhai, the Fulani use the term 'Jermabe' for the Zarma and those of sonankoobe for Songhai and this always means people of Songhai.

During the Zarma invasions, the Hausa term Zabarma was adopted by the Gurunsi, Dagomba and Akan of present-day Ghana, while the term Maraba and Diassarakan (army of the citadel) was used by the Senufo of the south and the Akan of the Ivory Coast

At the time of the Songhai Empire, the Songhai country was called 'The hump of the camel' by Arab writers.

The inhabitants of the cities of Timbuktu, Gao and Djenné are called koyraboro (The city dwellers) by the other inhabitants of the region in opposition to rural people and nomads, the term will later be generalized and used to designate all the Songhai living north of the current Mali, the Mandé use the term koroboro which is their Local pronunciation of koyraboro to designate the Songhai.

When Askia Muhammad the great is designated Caliph of the Sudan, the inhabitants of his country are also called Takruri.

The names used to designate the Songhai according to the country divides them into three groups:

- The Songhai-koyraboro of Mali.

- The Songhai-zarma of Niger, Nigeria, Burkina, Sudan.

- The Songhai-Dendi of Niger, Benin, Nigeria.

Genealogy

Raamah son of Cush (son of Ham) and qarnabil (daughter of Tiras) whose name means 'exalted', lofty, 'Thunder' is considered the ancestor of the Sabaeans, the Arabian Lihyanites and the Songhai through his son Dedan and Sheba.

Raamah also Called Mauretinos was the forebear of the Black Moors, from whom the region in North Africa bears its name. His name is generally associated with the biblical Raʻamah, and whose posterity were called Maurusii by the Greeks. In Tangier (the 1st Mauretania), the Black Moors were already a minority race at the time of Pliny, largely supplanted by the Gaetulians. According to R. Saadia Gaon (1984:32), the descendants of Raʻamah (Mauretinos) were thought to have settled Al-Kawkaw, possibly Gao, along the bend of the Niger River.

The Songhai themselves claim to descend from Song, who is either a person or a tribe, depending on the region.[10]

According to Songhai traditions, Zabar Khan, the father of Kiru and Naaki (Za el Yamen, the founder of the Za Dynasty) came from an ancient city located near Saham, in present-day Oman in southern Arabia, and which could be the ancient Reghma. The Songhai designate themselves as zaberbanda, the descendants of Za the Great (Zabar Khan); the term za hama (grandchildren of za) evolved to give Zarma in the East. Mali Bero, the great patriarch of the Zarma, and the emperors Sonni Ali Ber and Askia Muhammad trace their genealogy to Zabar Khan.[14][15]

Many present-day Songhai claim descent from 15th and 16th century emperors through the many descendants they had. Askia Mohammad I had 471 children from his many wives and concubines and his son Askia Daoud had 333, and their modern descendants are called Mamar haama; those of Sunni Ali Ber are called sy haama; and those of Mali Bero are called Mali haama where za haama.[16]

History

Za dynasty

The Za dynasty or Zuwa dynasty were rulers of a medieval kingdom based in the towns of Kukiya and Gao on the Niger River in what is today modern Mali. The Songhai people at large all descended from this kingdom. The most notable of them being the Zarma people of Niger who derive their name "Zarma (Za Hama)" from this dynasty, which means "the descendants of Za".[17][18]

Al-Sadi's seventeenth century chronicle, the Tarikh al-Sudan, provides an early history of the Songhay as handed down by oral tradition. The chronicle reports that the legendary founder of the dynasty, Za Alayaman (also called Dialliaman), originally came from the Yemen and settled in the town of Kukiya.[19] The town is believed to have been near the modern village of Bentiya on the eastern bank of the Niger River, north of the Fafa rapids, 134 km south east of Gao.[20] Tombstones with Arabic inscriptions dating from the 14th and 15th centuries have been found in the area.[21] Kukiya is also mentioned in the other important chronicle, the Tarikh al-fattash.[22] The Tarikh al-Sudan relates that the 15th ruler, Za Kusoy, converted to Islam in the year 1009–1010 A.D. At some stage the kingdom or at least its political focus moved north to Gao. The kingdom of Gao capitalized on the growing trans-Saharan trade and grew into a small regional power before being conquered by the Mali Empire in the early 13th century.

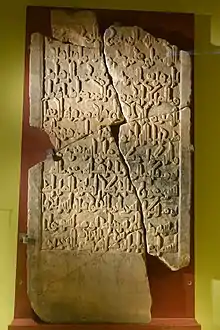

Gao Empire and Gao-Saney

Gao-Saney became well known among African historians because French administrators discovered here in a cave covered with sand in 1939 several finely carved marble stelae produced in Almeria in Southern Spain. Their inscriptions bear witness of three kings of a Muslim dynasty bearing as loan names the names of Muhammad and his two successors. From the dates of their deaths it appears that these kings of Gao ruled at the end of the eleventh and the beginning of the twelfth centuries CE.[23] According to recent research, the Zaghe kings commemorated by the stelae are identical with the kings of the Za dynasty whose names were recorded by the chroniclers of Timbuktu in the Ta'rikh al-Sudan and in the Ta'rikh al-Fattash. Their Islamic loan name is in one case complemented by their African name. It is on the basis of their common ancestral name Zaghe corresponding to Za and the third royal name Yama b. Kama provided in addition to 'Umar b. al-Khattab that the identity between the Zaghe and the Za could be established.

| Kings of Gao-Saney (1100 to 1120 CE)[24] | |||||||||||||

| Stelae of Gao-Saney | Ta'rīkh al-fattāsh | Ta'rīkh al-sūdān | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kings of the Zāghē | Date of death | Kings of the Zā | Kings of the Zā | ||||||||||

| Abū 'Abd Allāh Muhammad st. 1100 | st. 1100 | (16) Kotso-Dare | (16) Kusoy-Dare | ||||||||||

| Abū Bakr b. Quhāfa st. 1110 | st. 1110 | (17) Hizka-Zunku-Dam | (17) Hunabonua-Kodam | ||||||||||

| Umar b. al-Khattāb = | |||||||||||||

It appears from this table that Yama b. Kima (or 'Umar b. al-Khattab), the third king of the stelae of Gao-Saney, is identical with the 18th ruler of the list of Za kings. His name is given in the Ta'rikh al-Fattash (1665) as Yama-Kitsi and in the Ta'rikh al-Sudan (1655) as Biyu-Ki-Kima. On account of this identification the dynastic history of the Gao Empire can now to be established on a solid documentary basis.[25] Apart from some Arabic epitaphs on tombstones discovered in 1939 at the cemetery of Gao-Saney (6 km to the east of the city)[26] there are no surviving indigenous written records that date from before the middle of the 17th century.[27] Our knowledge of the early history of the town relies on the writings of external Arabic geographers living in Morocco, Egypt and Andalusia, who never visited the region. These authors referred to the town as Kawkaw or Kuku. The two key 17th century chronicles, the Tarikh al-Sudan and the Tarikh al-Fattash, provide information on the town at the time of the Songhai Empire but they contain only vague indications on the time before.[28] The chronicles do not, in general, acknowledge their sources.[29] Their accounts for the earlier periods are almost certainly based on oral tradition and for events before the second half of the 15th century they are likely to be less reliable. For these earlier periods the two chronicles sometimes provide conflicting information. The earliest mention of Gao is by al-Khwārizmī who wrote in the first half of the 9th century.[11] In the 9th century Gao was already an important regional power. Al-Yaqubi wrote in his Tarikh in around 872:

There is the kingdom of the Kawkaw, which is the greatest of the realms of the Sūdān, the most important and most powerful. All the kingdoms obey its king. Al-Kawkaw is the name of the town. Besides this there are a number of kingdoms of which the rulers pay allegiance to him and acknowledge his sovereignty, although they are kings in their own lands.[30]

In the 10th century, Gao was already Muslim and was described as consisting of two separate towns. Al-Muhallabi, who died in 990, wrote in a lost work quoted in the biographical dictionary compiled by Yaqut:

Their king pretends before his subject to be a Muslim and most of them pretend to be Muslims too. He has a town on the Nile [Niger], on the eastern bank, which is called Sarnāh, where there are markets and trading houses and to which there is continuous traffic from all parts. He has another town to the west of the Nile [Niger] where he and his men and those who have his confidence live. There is a mosque there where he prays but the communal prayer ground is between the two towns.[31]

The archaeological evidence suggests that there were two settlements on the eastern bank of the Niger:[32] Gao Ancien situated within the modern town, to the east of the Tomb of Askia, and the archaeological site of Gao-Saney (Sané in French) situated around 4 km to the east. The bed of the Wadi Gangaber passes to the south of the Gao-Saney occupation mound (tell) but to the north of Gao Ancien. The imported pottery and glass recovered from Gao-Saney suggest that the site was occupied between the 8th and 12th centuries.[33] It is possible that Gao-Saney corresponds to Sarnāh of al-Muhallabi.[34] Al-Bakri writing in 1068 also records the existence of two towns,[35] but al-Idrisi writing in around 1154 does not.[36] Both al-Muhallabi (see quote above) and al-Bakri[37] situate Gao on the west (or right bank) of the Niger. The 17th century Tarikh al-Fattash also states that in the 10th century Gao was situated on the Gourma side (i.e. the west bank) of the river.[38] A large sand dune, La Dune Rose, lies on the west bank opposite Gao, but at Koima, on the edge of the dune at a site 4 km north of Gao, surface deposits indicate a pre 9th century settlement. This could be the west bank Gao mentioned by 10th and 11th century authors. The site has not been excavated.[39]

Al-Sadi in his Tarikh al-Sudan gives a slightly later date for the introduction of Islam. He lists 32 rulers of the Zuwa dynasty and states that in 1009–1010 A.D. the 15th ruler, Zuwa Kusoy, was the first to convert to Islam.[40]

Towards the end of the 13th century, Gao lost its independence and became part of the expanding Mali Empire.[41] What happened to the Zuwa rulers is not recorded.[42] Ibn Battuta visited Gao in 1353 when the town formed part of the Mali Empire. He arrived by boat from Timbuktu on his return journey from visiting the capital of the Empire:

Then I travelled to the town of Kawkaw, which is a great town on the Nīl [Niger], one of the finest, biggest, and most fertile cities of the Sūdān. There is much rice there, and milk, and chickens, and fish, and the cucumber, which has no like. Its people conduct their buying and selling with cowries, like the people of Mālī.[43]

After staying a month in the town, Ibn Battuta left with a caravan for Takedda and from there headed north back across the Sahara to an oasis in Tuat with a large caravan that included 600 slave girls.

Sometime in the 14th century, Ali Kulun, the first ruler of the Sunni dynasty, rebelled against Mali hegemony, and was defeated.;[44][45] It was not until the first half of the 15th century that Sunni Sulayman Dama was able to throw off the Mali yoke. His successor, Sunni Ali Ber (1464–1492), greatly expanded the territory under Songhay control and established the Songhay Empire.

Rule of the Mali Empire

Towards the end of the 13th century, Gao lost its independence and became part of the expanding Mali Empire.[41]

According to the Tarikh al-Sudan, the cities of Gao and Timbuktu submitted to Musa's rule as he traveled through on his return to Mali.[46] According to one account given by Ibn Khaldun, Musa's general Saghmanja conquered Gao. The other account claims that Gao had been conquered during the reign of Mansa Sakura.[47] Both of these accounts may be true, as Mali's control of Gao may have been weak, requiring powerful mansas to reassert their authority periodically.[48] Both chronicles provide details on Ali Kulun (or Ali Golom) the founder of the Sunni dynasty. He revolted against the hegemony of the Mali Empire. A date is not given in the chronicles but the comment in the Tarikh al-fattash that the fifth ruler was in power at time when Mansa Musa made his pilgrimage[49] suggests that Ali Kulun reigned around the end of the 14th century.[41]

Both chronicles associate Ali Kulun (or Ali Golom) with the Mali court.[50] The Tarikh al-Sudan relates that his father was Za Yasoboy, and as a son of a subordinate ruler of the Mali Empire, he had to serve the sultan of Mali.[51]

The chronicles do not specify where the early rulers lived. As there is evidence that Gao remained under Mali control until the early fifteenth century, it is probably that the early Sunni rulers controlled a region to the south, with the town of Kukiya[52] possibly serving as their capital.[44] As the economic strength of Mali Empire relied on controlling routes across the Sahara, it would not have been necessary to control the area to the south of Gao.

Al-Sadi, the author of the Tarikh al-Sudan uses the word Sunni or Sonni for the name of the dynasty while the Tarikh al-fattash uses the forms chi and si'i.[53] The word may have a Malinke origin meaning "a subordinate or confidant of the ruler".[54]

Under the rule of Sunni Sulayman, the Songhai captured the Mema region to the west of Lake Débo.[55]

Songhai Empire

In 1464, the Songhai seceded from the declining Mali Empire, the Songhai country regained its total independence.

Formerly one of the peoples subjected by the Mali Empire, the Songhai asserted their control of the area around Gao after the weakening of the Mali Empire, founding the Songhai Empire which came to encompass much of the former Malian territories, including Timbuktu, famous for its Islamic universities, and the pivotal trading city of Djenné, and extending their rule over a territory that surpassed the former Mali and Ghana empires. Among Songhai's most noted scholars was Ahmed Baba— a highly distinguished historian frequently quoted in the Tarikh al-Sudan and other works. The people consisted of mostly fishermen and traders. Following Sonni Ali's death, Muslim factions rebelled against his successor and installed the general Askia Muhammad (formerly Muhammad Toure) who was to be the first and most important ruler of the Askia dynasty (1492–1592). Under the Askias, the Songhai empire reached its zenith.[56]

Songhai Empire Decline

In 1528, Askia's children revolted against him and declared his son Musa king. Following Musa's overthrow in 1531, the Songhai Empire went into decline.

Between the political chaos and multiple civil wars within the empire, it came as a surprise when Morocco invaded Songhai unexpectedly. The Moroccan invasion of Songhai was mainly to seize control of and revive the trans-Saharan trade in salt and gold. During Askia's reign, the Songhai military consisted of full-time soldiers, but the king never modernized his army. On the other hand, the invading Moroccan army included thousands of arquebusiers and eight English cannons. In the decisive Battle of Tondibi on 13 March 1591, the Moroccans destroyed the Songhai army and proceeded to capture Gao and Timbuktu, marking the end of the empire.

After the empire's defeat, the nobles moved south to an area known today as Songhai in present Niger, where the Sonni dynasty had already settled. They formed smaller kingdoms such as Wanzarbe, AyerouGothèye, Dargol, Téra, Sikié, Kokorou, Gorouol, Karma, Namaro and further south, the Dendi which rose to prominence shortly afterwards.

Kingdom of Dendi

Under the Songhai Empire, Dendi had been the easternmost province, governed by the prestigious Dendi-fari ("governor of the eastern front").[57] Some members of the Askia dynasty and their followers fled here after being defeated by the invading Saadi dynasty of Morocco at the Battle of Tondibi and at another battle seven months later. There, they resisted Moroccan Invaders and maintained the tradition of the Songhai with the same Askia rulers and their newly established capital at Lulami.[58] The first ruler, Askia Ishaq II was deposed by his brother Muhammad Gao, who was in turn murdered on the order of the Moroccan pasha. The Moroccans then appointed Sulayman as puppet king ruling the Niger between Djenné and Gao. South of Tillaberi, the Songhai resistance against Morocco continued under Askia Nuh, a son of Askia Dawud.[59] He established his capital at Lulami.[60][61]

Arma Pashalik of Timbuktu

In 1591, a Moroccan force which left Marrakesh with between three and four thousand soldiers, together with several hundred auxiliaries[62] defeated the Songhai army at Tondibi and conquered Gao, Timbuktu and Djenné. The Pashalik of Timbuktu was then established and Timbuktu became its capital. Starting from 1618, the Pasha, who was then appointed by the Sultan of Morocco, became elected by the Armas.[63] However, while governing the Pashalik as an independent republic, the Armas continued to recognize Moroccan sultans as their leaders. During the civil war that followed the death of Ahmad al-Mansur in Morocco, the Pashalik supported the legitimate Sultan, Zidan al-Nasir,[64] and in 1670 they recognized the Alaouite sultans and pledged allegiance.[65] This however, was not to last for long; as the Pashalik was to revoke Moroccan suzerainty by the early eighteenth century. This event is preserved in local traditions as caused by the actions of an erudite scholar by the name of Gurdu, who is said to have put an end to slavery with supernatural powers he had. The tradition goes that he sent the youngest of his pupils to sign a document stating to never ask for a yearly exchange of slaves from Timbuktu again.[66] By the middle of the eighteenth century, the pashalik was in total eclipse. In about 1770, the Tuareg took possession of Gao, and in 1787 they entered Timbuktu and made the Pashalik their tributary.[67]

Zabarma Emirate (1860-1897)

The Zabarma Emirate was an Islamic state that existed from the 1860s to 1897 in what is today parts of Northern Ghana and Burkina Faso. Although founded by the Zarma people, the Zabarma Emirate was a very heterogeneous entity in which the Zarma were actually only a minority. It was mainly Hausa, Fulani, Mossi and most importantly the Gurusi people who were their main allies and army men.

The name Gurunsi actually comes from the Zarma language "Guru-si", meaning "iron does not penetrate". It is said that during the Zarma conquest of Gurunsi lands in the late 19th century, the Zarma leader by the name of Baba Ato Zato (better known by the Hausa corruption of his name: Babatu) recruited a battalion of indigenous men for his army, who after having consumed traditional medicines, were said to be invulnerable to iron.

In 1887, Zabarma Emirate forces raided Wa the capital of the Kingdom of Wala and caused much of the population to flee.[68]

This was the genesis of the play and ethnic slavery jokes that exist between the Zarma and Gurusi of Ghana till this day.

Despite being a minority, the Zarma were able to secure the services of their followers of different origins, coupled with a rather long-lasting loyalty.

The Emirs of the Zabarima Emirate are: 1. Hanno or Alfa Hanno dan Tadano 2. Gazari or Alfa Gazare dan Mahama 3. Babatu or Mahama dan Issa (Babatu in colonial literature )

Together with their local allies, the French successfully defeated Babatu and his Zarma army on March 14, 1897, at Gandiogo. The rest of Babatu's troops were defeated again on June 23, 1897, at Doucie. The survivors of this battle then fled south, prompting the British to take military action against them in October 1897. The fighting lasted until June 1898, when the last resistance of Babatu's former private army was finally defeated.

As the British military presence continued to grow in Gambaga and other areas east of the Black Volta, many of the remaining authorities of the Zabarma Emirate in the Gurunsi area fled eastward towards Dagbon.[69]

Maraba kingdom

Then the zarma warriors and traders from the Niger valley east of Niamey attacked the Tagwana and Djimini defeating the former and signing a truce with the latter. A second Zarma attack brought all the Southern Senufo to the arms, and zarma retreated to the frontier with the Baoulé (1895) where they founded Marabadiassa, Mori Touré the warlord King of Maraba made the city a war capital and an Islamic commercial center attracting merchants and religious especially Mandé. The zarma rallied to Samori Toure and attacked the Senufo again.[70] Mori Touré dissuades Samori Toure not to attack the Baoulé People of Bouaké and the latter choose to be a protectorate of Maraba. Mori Touré gives dabakala to his friend Samori Toure to make it a stationing camp for the army of the wassoulou, the two organize several wars in the region before samori continues to the Zabarma Emirate. At its height, the Maraba conquered Katyono, Timbe and Katiola thus becoming the master of a territory extending from Dahakoloaa to the border of Baoulé and Bandama River to the N'zi. A mortal Zarma attack on Katiola led to a vast migration of Senufo from the south and great societal changes in the center and south of northern Ivory Coast.

Military

The 15th-16th and 19th centuries are the periods of great Songhai conquests, with the formation of formidable army commanded by great conquerors. Riders of the wide open spaces of the Sahel and the Sudanese savannah the Songhai will carve out in the 15th-16th century the largest empire of African history thanks to a powerful army composed by Navy (400 under the reign of Sunni Ali Ber and more than 2000 under the Askia dynasty), fast riders, mounted archers, infantryman, camel riders, expert in besieging cities, expert in digging canals, architect builders of walls, low walls, fortress, bulls trained to break enemy ranks.[71] Sunni Ali Ber waged 32 wars in 27 years and won them all, Askia Muhammad would expand the Songhai Empire from the senegambian atlantic to the lake chad basin in northern Nigeria and from the Algerian tuat to the Guinean forest thus becoming the most powerful ruler of West Africa.

The army of the Songhai Empire called sona is a medieval army that fights with swords, arrows and spears, while the guru si (the invulnerable to iron) of the Zabarma Emirate and the army of Mori Touré are equipped with gun and cannon, these are gunpowder state like the Toucouleur Empire and Wassoulou Empire.[69]

During the conquest of Timbuktu in 1468, Sunni Ali Ber dug a Cannals from the river to the city in order to pass part of his fleet of 400 ships, he used it to attack the city. He employed 24,000 prisoners of war to achieve this. After the conquest, they massacre a good part of the inhabitants of the city.[72]

In 1473, Sunni Ali Ber besieged Djenné with his 400 ships filled with archers (The Tongo led by the Tongofarma) and riders with pointed Helmets and dressed in Chain mail, He took the city after seven months and seven days of siege.[73]

In 1483, to suppress the Massina revolt and the assassination of Songhai traders, Sonni Ali Ber besieged the entire Inland Niger Delta with his fleet and carried out a harsh repression that cost nearly one million people killed. the Tarik Al fattash reports that the survivors can fit under a single genealogical branch.

The armies of the zabarma invasions of the 19th Century will be the basis of many conquests and destruction in the Sudanian savannah, known by the nickname of vulture riders or guru si, invulnerable to iron, they plundered a vast region corresponding to parts from Burkina Faso, Ghana and present-day Ivory Coast. The beats of the great war drums called tubal gave the signal for war, the army of the Songhai Empire moved in a fan accompanied by the sounds of the long trumpets called kakaki.

Niani, the capital of the Mali Empire was razed in 1545 after having served as the headquarters of the Songhai army after its conquest and the emperor's palace had been defiled and transformed into toilets under the orders of the future Askia Ishaq II After the conquest of a city.

In 1514-1515, Askia Muhammad, the emperor of Songhai at the time directed with his aide camp and general, the Kanta Kotal, military conquests towards East, they invaded Aïr and the Hausaland, they made the conquest of Agadez, kano, Gobir, Zazzau, katsina, Daura, Zamfara and plunged to lands located in present-day Cameroon, raids were also carried out against the Kanem Bornu. In the heart of the land battles, the Songhai archers forming rows behind low walls and on earthen turrets are preceded by the horse and camel riders, the infantry pushing in front of them raging bulls, this is how the Songhai then achieved the conquest of vast contiguous territory.[74]

The greatest defeats of the Songhai are those of the Battle of Tondibi, on March,13,1591, facing the invading army of the saadian of Morocco, Ishaq II, the emperor of Songhai at the time discovered for the first time the power of firearms in front of which he then opposed only 12,500 cavalry men, 9,700 infantry and 1,000 attacking bulls, the defeat of tondibi sounded the fall of the Songhai Empire. The Moroccan army of invasions composed of Turkish instructors, Danish, French, British and Arabs placed under the command of Judar, a Spanish enuque with blue eyes, the army was made up of 2,500 men of infantry equipped with arquebuses, 500 men equipped with arrows, swords and spears, 1,500 light cavalry and six cannons carried on camels.[75][76]

The guerrillas led by askia Nuh and the dendifari hawa-ize against the Moroccans prevented them from conquering the dendi, the Moroccans are beaten at the battle of tondidaru, 200 of their men killed by Songhai armed with rifles and their kasbah of kulen destroyed.[76]

The Songhai mainly offered two choices to the conquered population, integrate into the armies of the invasions or to be sold as slaves. The Diassarakan ethnic group from the center of the Ivory Coast comes from the zarma invaders of the tagbana and djimini countries, their name means the army of the citadel, the garrisons of the citadel in the Mandé language. Bouaké the great city of the baoulé was placed under their protectorate [77]

The army of the Zabarma Emirate was divided into eight companies mainly composed of the defeated populations placed under the command of the Songhai conquerors and scarred according to their company so that it could be recognized and not flee, having no fixed capital, the Zabarma Emirate directed all its invasions from military camps, the most famous of which was kasena near Tumu, they sometimes settled for a time in a city destroyed during the conquest as in Wa[68] and to seti.

In Nasa in (1890), the Emir Babatu (warlord) said zataw (The devil) of Zabarma Empire at the head of his 9,000 riders defeated the 12,000 men of the army of bazori, king of Wala, he took his capital Wa and massacred 100,000 inhabitants of the city. According to the local sources, the city delivered the flame was partly destroyed after an explosion of gunpowder stores and the scholars sold to the north, Babatu made the city his headquarters before invading seti in issala where he beheaded more than 12,000 inhabitants of the city. The following year, he marched on Ouagadougou, the capital of the Mossi Empire, empty of these inhabitants before his arrival, he occupied the city and abandoned it after negotiation of the yatenga. He returned to his camp of kassena leaving a garrison in Tenkodogo.

The armies of Sunni ali ber and Babatu (warlord) were known to be accompanied by numerous columns of Vultures during their expeditions, hence their name of vulture riders.[78] Their horses' hooves echoing across the vast plains made even the greatest cities shudder with dread.

Languages

The Songhay languages is called ayneha chiine by the Songhai themselves, ayneha means 'I said', the variants are named according to the sub-groups that speak them (ex: Zarma: Zarma Senni).

Classification

The Songhay languages is classified in the group of Nilo-Saharan languages which also includes Nubian, Kanuri, Turkana, Maasai and other Nilotic and Maban languages, the classification of Songhai nevertheless remains controversial due to its strong Afro-Asiatic lexicon and its structure close to the Mandé languages, Nicolaï considers Songhai as a Berber creole, others like Gerrit Dimmendaal consider Songhai as an isolated language. The Nilo-Saharan hypothesis traces the origin of Songhai to the 7th millennium when the first speakers (Nomadic pastoralists of the Holocene) left the Nile valley to head towards the Aïr massif before continuing towards the loop of the Niger where it founded kukya.[79]

The geographical remoteness of Songhai from the other Nilo Saharan languages spoken in East Africa and Central Africa is the source of its differentiation from the other languages of the group. The foreign influences on Songhai would originate from the very turbulent history of the speakers who had to found great centers of knowledge, powerful and largest Empires.

History of Songhai language expansion

The evolution of the Songhai language can be divided into five phases: Holocene Songhay, Ancient Songhai, Upper Songhai,Medieval Songhai, and Modern Songhay dialect. Each of its phases is linked to a phase in the history of language speakers.

The Proto-Songhay is those of Nomadic pastoralists originating from the Nile valley and which greatly influenced the Chadic languages, The ancient Songhai spoken by the inhabitants of the kingdom of Kukya evolves in upper Songhai at the time of Gao Empire. Main regional powers in the Sahara-Sahel zone the Gao Empire traded with the Caliphate of Cordoba, the Berbers and Jewish populations of North Africa fleeing the persecutions of the Arab invaders migrated to the Gao Empire, it is from there that the first waves of migrants will influence Songhay and adopt Songhay as their mother tongue, certain groups going further east will found the kingdom of Takedda where tishishit will develop. A colony of Songhai traders will found Tabelbala as a relay caravanserai between the Gao Empire and Muslim Spain. The songhay languages speak in the Gao Empire is the upper Songhai south while the Songhai speak in Takedda is the Northern upper Songhai.

Upper Songhai evolves into medieval Songhai between the periods of domination of the Mali Empire and in that of expansion of the Songhai Empire with the development of great centers of knowledge and trade such as Djenné, Gao and Timbuktu. Humburi senni is considered the closest dialect to medieval Songhai.

The fall of the Songhai Empire in 1592 led to the dispersal of many Songhai across the region, especially towards the west of Niger where the resistant kingdom of the dendi would be formed.

The disintegration of the dendi in several historical regions and the Moroccan influence in Djenné in Timbuktu allowed the formation of the many dialects known today.

The expansion of the dendi and its formalization in Parakou, Kandi, Djougou in bariba and yom country is the work of Songhai merchants and scholars.

The tassawaq, the emghedezi and the igdalan born from the break-up of the kingdom of takedda for the benefit of the sultanate of agadez continued to exist with the exception of the emghedezi which disappeared with the adoption of the Hausa language by the population of agadez

The Zabarma invasions in the 19th century did not allow an expansion of the Songhay language in the invaded regions due to the numerical weakness of the Songhai against the conquered population and the presence of the two major lingua francas of West Africa (Hausa and Mandé).

Hausa is used as a lingua franca in the Zabarma Emirate and will remain so even after its dispersion in the dominated regions, from there it will be taken up throughout Ghana to become the language of the Zongo, it is Ghaananci. In maraba it is the Mandé which will impose itself as the official language and this will result in a linguistic, cultural and ethnic assimilation of the Songhai by the Mandinka.

The Songhai language is also spread on the road to the hajj, especially in the Sudan where the Zabarmawi form a large community, the language is spoken there with a strong influence of Sudanese Arabic but it tends to disappear today with the youngest.

The Songhai settled in what is now Nigeria from the invasions of the Songhai Empire to the Moroccan invasion and the wars against Sokoto and European colonizers, the Songhai of Nigeria form the 3rd Songhai community. Recent migrations to coastal countries have also brought Songhai speakers to these countries (Ghana, Togo, Ivory Coast).

The dialects of the Songhai language

The Songhai language is divided into two groups: the Northern Songhai languages spoken by nomadic populations and inhabitants of the oases, and the Southern Songhai language spoken by sedentary populations.

The Northern Songhai languages are the korandje language of the belbali of Tabelbala in Algeria, the Tadaksahak of the Nomadic Idaksahak, the group called Tishishit which includes the Tagdal language of the Nomadic Igdalen, the Tasawaq of the Isawaghan of ingal and Teguida n'tessmt, the extinct emghedezi of the city of Agadez.

The Southern Songhai languages include Zarma (standard Songhai and dialect with the most speakers) of the Zarma of Niger, Nigeria, Burkina Faso, Sudan, Ghana, Benin with its influential group called the Songhaybore senni of the Songhai proper,[80] the koyraboro Senni of Gao, the koyra Chiini language of Timbuktu with its western group of Djenne called Djenné chiine, the Humburi Senni of Hombori, the Tondi Songway Kiini (speaking of the mountainous Songhai) of the mountainous massif of gandamia, the Dendi language of Niger, Benin and Nigeria.[81]

Songhai is the main lingua franca of Northern Mali and western Niger. Songhai-speaking towns are Niamey, the capital of the Republic of Niger, Dosso and Tillabéri, the historic towns of Djenné, Gao, Timbuktu.

Grammar

Songhay is mostly a tonal, SOV group of languages, an exception being the divergent Koyra Chiini of Timbuktu, which is non-tonal and uses SVO order.

Songhay has a morpheme -ndi which marks either the causative or the agentless passive. Verbs can even take two instances of the morpheme, one for each meaning. Thus ŋa-ndi-ndi figuratively translates to "[the rice] was made to be eaten [by someone: causee] [by someone: causer]".[82]

Ethnicity

The Songhai people are made up of several ethnic groups, themselves made up of several subgroups and clans . If some ethnic groups are recognized as being of authentic Songhai descent, others have become so by assimilation throughout history through various means, the za dynasty or zaghe remains the backbone to which it all has become to aggregate. If the tarikh and the oral tradition evoke a southern Arabian origin of the dynasty (probably from the kingdom of axum which dominated southern Arabia at the time when the zaghe settled in the sahel and whose names of the sovereigns resemble those of the za ) and that European researchers see rather a Berber origin, the origin of the Za dynasty remains unclear as the classification of the Songhai language and the resolution of one of the dilemmas will bring that of the other. In the 11th century a tension leads to a division of the dynasty into two branches, an eastern branch having continued to lead the Empire of Gao and at the origin of the Sunni dynasty and Askiya dynasty and a dissident western branch which migrated to the region of Timbuktu. The development of the Gao Empire and the rise of the songhai commercial towns of the loop of the Niger allowed the installation in Songhai country of traders of various origins (Mandé, sanhadja, soninké, Tuareg, Peulh, Arabs...) who at the time was married and assimilated to the indigenous Songhai population . In the 8th century traders of Arab origin brought Islam to Songhai and cities like Timbuktu and Gao became poles of knowledge attracting even more people, the peak of the confluence of people on the bend of the Niger begins with the Mali Empire and continues with the native Songhai Empire which promotes the installation of Arab families from the Near East and Sephardic Jews of Sahara Expert in agriculture converted to Islam by the Askiya emperors, all these newcomers at the time of the power of Songhai, adopt the language of the leaders and are assimilated by the Songhai, an urban elite called koyrabore (people of the city) is formed in the big cities with the Koyra Chiini (Timbuktu) and Koyraboro Senni (Gao) dialects of Songhai as a language, it is to this category of Songhai that belongs Ahmad Baba al-Timbukti, Mahmud Kati and others . slaves brought from conquered countries are also assimilated to the culture of the country by their Songhai masters .[17]

- The conquest of Djenne by Sonni Ali Ber was the starting point for the assimilation to Songhai of the populations of the region, the installation of garrison, the marriage between Sonni ali ber and the queen of Djenné, the importance of Djenné in As a market and center of knowledge, many Songhai migrated to the area, the newcomers made their language the main language of the city and all the Eastern Mandé peoples and Eastern Macina Fula assimilated into Songhai koyraboro and created a new variety of Songhai, the Djenné Chiini derived from Koyra Chiini.[73]

- The western zaghe separated from the eastern zaghe began during the Songhai Empire a migration from their location in the dirma near Timbuktu to the East under the leadership of the patriarch divided into 7 clans following conflict with other groups, they begin a pastoral migration which will bring them to the west of the current Republic of Niger, they are at the origin of the Zarma people and the idaksahak according to oral tradition, the Sambo patriarch is described as the ishak brother, the ancestors of the idaksahak, on their arrival they settled on the plateau which they baptized zarmaganda (the heart of the zarma) and found on the spot Songhai and non-Songhai clans which they assimilated, with the fall of the Songhai Empire, princes of songhai took refuge in the south and linked up with the zarmas, at the time of the clan zarmas separated from those of zarmaganda to occupy the various other parts of western Niger, the waazi occupied the plateau of zidji and founded the kingdom of Dosso, the sega where tobili occupies the valley of the boboye where they hunt the mossi of the East, the fahmey occupies the plateau of the fakara, the kogori and the namari occupy the valley of the river and call all the region zarmatarey( the country of the zarmas), he thus founded two groups of distinct principalities, the principalities of zarmaganda and the principalities of zarmatarey, the zarma groups of zarmaganda are called kalley and those of zarmatarey golley, each principality is led by a zarmakoy whose power is symbolized by a drum of wars called toubal.[83][84]

- After the seizure of power by Askya Mohamed, the deposed emperor sonni barou and his suite settled in the Dendi where they founded ayorou, joined by the Askya with the Moroccan invasion, they founded together several principalities (Téra, Namaro, kokorou, Dargol, Sikié, Gothèye, gorouol, Karma.. )in the right bank (gourma) on the plateau of liptako-Gourma in front of zarmaganda and zarmatarey that he will baptize sonhoy (The Songhai) in memory of their fallen empire and call themselves sonhoyboro (Songhai proper) he speaks Songhoyboro Ciine dialects of zarma arrived in the gourma they found it occupied by the gourmantché whom they hunted for some, and assimilated by slavery or by neighborhood for others, it constitutes a subgroup of the zarma, because they also descend from za where zaghe, they are the political and military allies of their cousins of zarmatarey and zarmaganda during all the wars against the Sokoto Empire, the Tuareg confederations and during the zarma invasions on the voltaic plateau.[85][86]

- Fulani clans from macina under the leadership of their leader Malick settled near the proper songhai of the river and assimilated linguistically and ethnically to them to form a new songhai sub-group called Kurtey people, the name kurtey derives from songhai kuru (herd ) and teh (it is realizing), when the men returned from the war the women cried kurutey: the herd its realizing. the kourtey were born from the Fulani and Songhai interbreeding, the kourtey generally live on the islands of the river and were once known for their raids on the neighboring populations, they arrived on the canoes to take away man, cattle, gold.[87]

Society

The language, society and culture of the Songhai people is barely distinguishable from the Zarma people.[88] Some scholars consider the Zarma people to be a part of and the largest ethnic sub-group of the Songhai.[89] Some study the group together as Zarma-Songhai people.[90][91] However, both groups see themselves as two different peoples.[88]

Social stratification

The Songhai people have traditionally been a socially stratified society, like many West African ethnic groups with castes.[92][93] According to the medieval and colonial-era descriptions, their vocation is hereditary, and each stratified group has been endogamous.[94] The social stratification has been unusual in two ways; it embedded slavery, wherein the lowest strata of the population inherited slavery, and the Zima, or priests and Islamic clerics, had to be initiated but did not automatically inherit that profession, making the cleric strata a pseudo-caste.[88]

Louis Dumont, the 20th-century author famous for his classic Homo Hierarchicus, recognized the social stratification among Zarma-Songhai people as well as other ethnic groups in West Africa, but suggested that sociologists should invent a new term for West African social stratification system.[95] Other scholars consider this a bias and isolationist because the West African system shares all elements in Dumont's system, including economic, endogamous, ritual, religious, deemed polluting, segregative and spread over a large region.[95][96][97] According to Anne Haour – a professor of African Studies, some scholars consider the historic caste-like social stratification in Zarma-Songhay people to be a pre-Islam feature while some consider it derived from the Arab influence.[95]

The different strata of the Songhai-Zarma people have included the kings and warriors, the scribes, the artisans, the weavers, the hunters, the fishermen, the leather workers and hairdressers (Wanzam), and the domestic slaves (Horso, Bannye). Each caste reveres its own guardian spirit.[92][95] Some scholars such as John Shoup list these strata in three categories: free (chiefs, farmers, and herders), servile (artists, musicians and griots), and the slave class.[98] The servile group was socially required to be endogamous, while the slaves could be emancipated over four generations. The highest social level, states Shoup, claim to have descended from King Sonni 'Ali Ber and their modern era hereditary occupation has been Sohance (sorcerer). Considered as being the true Songhai,[4] the Sohance, also known as Si Hamey are found primarily in The Songhai in the Tillabery Region of Niger, whereas, at the top Social level in Gao, the old seat of the Songhai Empire and much of Mali, one finds the Arma who are the descendants of the Moroccan invaders married to Songhai women.[99] The traditionally free strata of the Songhai people have owned property and herds, and these have dominated the political system and governments during and after the French colonial rule.[98] Within the stratified social system, the Islamic system of polygynous marriages is a norm, with preferred partners being cross cousins.[100][101] This endogamy within Songhai-Zarma people is similar to other ethnic groups in West Africa.[102]

Livelihood

The Songhai people cultivate cereals and raise small herds of cattle and fish in the Niger Bend area where they live.[100] They have traditionally been one of the key West African ethnic groups associated with caravan trade.[100]

Culture

The Songhai being Sahelosaharians they share a broad culture in common with their immediate Sahelian neighbors who are the Tuareg, and Mandinka with whom they have the most cultural affinity, then the Arabs of the Sahel and the Maghreb followed by the Hausa, the Fula people and others Sahelian group both Afro-Asiatic and Nilo-Saharan, to the east in Sudan they have adopted several cultural characteristics from the Sudanese Arabs, Nubians, and Beja people.

Economy

The proto-Songhay (Nilo-Saharan or Afro-asiatic pastoralists of Neolithic) who migrated in the 4th millennium BC from North East Africa (Nile Valley) to the central Sahara (Aïr Mountains) were essentially nomadic pastoralists. Their settled descendants are partly farmers, breeders, traders, caravanners, fishermen, hunters, sedentary craftsmen occupying large historic cities and large villages and for another part nomadic herders camel breeders in the immensities of the Sahara and living in nomadic tents.

Agricultural activities

Agriculture is the primary activity of the Songhai populations. As they live in arid and semi-arid areas the agriculture is seasonal. The rainy season in the Sahel extends over three months, compared to eight to nine dry months. Irrigation is widely practiced near the river and in the oases. The Songhai mainly cultivate cereals; their most produced crop is millet, followed by rice grown on the banks of the Niger River, then wheat and sorghum. As elsewhere in the central Sahel, maize is grown less. Cereals that grow wild are also picked in season, such as panicum leatum or wild fonio. Other crops widely cultivated by the Songhai are tobacco, onions, spices, tubers and moringa. Date palms are cultivated by irrigation in the oases of the Sahara, e.g. Tindouf, Tabalbala and Ingal. Mango is the most widely produced fruit, followed by oranges, watermelons, melons and gourds.

The Songhai practice agriculture with plows pulled by oxen. Unlike the Hausa people, who mainly use the daba to cultivate, the Songhai more commonly use the hilar, the hoe, and the pitchfork.

In precolonial times, before the abolition of slavery by the French in the Sahel, the Songhai employed hundreds or even thousands of servile labor razzier. Following modernization agricultural equipment such as tractors and combine harvesters is widely used. Agricultural workers known as boogou are organized to help farmers with less labor. After the harvest the Songhai leave their fields to the Fulani and Tuareg herders so that their cattle clean the fields; Songhai who have large herds let their own cattle clean the fields.

Animal husbandry

The Songhai practice animal husbandry according to their way of life. The people settled in and around villages raise mainly cattle, goats (especially the Sahelian breed), sheep, poultry (especially guinea fowl), and donkeys. Camels are raised for travel and also consumption, especially in the zarmaganda, in Gao and Timbuktu.

Nomadic idaksahak and igdalen pastoralists breed large livestock. The families of breeders travel the valleys of the azawakh, the azgueret, the irhazer, the tilemsi, the banks gourma of the river and the foothills of the mountains of Aïr and Adrar of the iforas. Their herds are primarily constituted of camels, but they also herd goats, sheep and oxen. They live in tents and eat mainly dairy products.

The horse is a central element of Songhai society. The Songhai country is widely known as the land of horses, and the Songhai have developed their own breeds of horses: the djerma is a cross between the Dongola and the barb, raised along the Niger River; and the Bagzan from the Aïr Mountain, which is prized for war. The Niger rivals the Ethiopian plateau in terms of horse ownership. The Songhai introduce their children to horses from adolescence. Nobles possess large quantities of horses, which are used for parades, surveillance of cattle and fields. The Songhai languages have names for any type and coat of horse. In Songhai country, the value of a man was measured in terms of the nobility of his horse. Historically, the Songhai delegated guarding and the maintenance of their horses to their most trustworthy captives. Villages used to hold horse racing competitions especially on market days.

Notable Songhai people

Leader

- Za el-Ayamen: Founder of Gao Empire

- Sonni Ali Ber (1464-1492): Military leader, conqueror, founder and 1st Emperor of Songhai Empire.

- Sonni Baru ( 1492-1493): emperor of Songhai Empire

- Askia Muhammad(1493-1529): founder of Askia dynasty, Emperor of Songhai Empire, Caliph and Amir al-Mu'minin of Land of black.

- Askiya Musa (1529-1531): emperor of Songhai Empire.

- Askia Muhammad Bonkano (1531-1537): emperor of Songhai Empire.

- Askiya Isma'il (1537-1539): emperor of Songhai Empire.

- Askiya ishaq I (1539-1549): emperor of Songhai Empire.

- Askiya Dawud (1549-1582 or -1583): emperor of Songhai Empire.

- Askiya Mohammad El haj (1582-1586): emperor of Songhai Empire.

- Askiya Muhammad Bani (1586-1588): emperor of Songhai Empire.

- Askiya Ishaq II (1588-1592): emperor of Songhai Empire.

- Zarmakoy Sambo : zarma migration patriarch.

- Babatu: Military leader and 3rd Emir of Zabarma Empire

- Djibo Bakary: president of the government council of Niger and leader of Sawaba party.

- Hamani Diori: 1st president of Niger Republic (1960-1974)

- Seyni Kountche: Military President of the Republic of Niger (1974-1987) and Head of the CMS, High Supreme Military Council (exceptional regime).

- Ali Saibou: Chief of the High Supreme Military Council and 3rd President of Niger (1987-1993).

- Ibrahim Hassane Mayaki:Prime Minister of Niger from 27 November 1997 to 3 January 2000.

- Amadou Toumani Touré: Army general and 4th President of Mali from 8 June 2002 to 22 March 2012.

- Salou Djibo: Army corps general, Chairman of the Supreme Council for the Restoration of Democracy. President of Niger from 18 February 2010 to 7 April 2011.

- Madaki Hawa Askya (15th-16th centuries): Daughter of Emperor Askia Muhammad I, wife of Sultan Muhammad Rumfa of the Sultanate of Kano, Queen of Kano, initiator of the office of Madaki in the Hausaland and grandmother of Sultan Muhammad Kisoki.

Intellectual

- Doctor Aben Ali ( 14th-15th centuries), Doctor at the Imperial Court of Gao, Doctor to Princess Salma Kassay, Doctor to Charles VII King of France on March 4, 1419, Founder of the traditional medicine Office in Toulouse, France.

- Mahmud Kati (1468-1552) Scholars of Timbuktu, Askia Muhammad I secretary, author of Tarikh al-fattash from Songhai Koyraboro subgroup.

- Mohammed Bagayogo (1523-1593]]: Sheikh, teacher of Sankore Madrasah, Philosopher, Arabic grammarian, from Songhai Koyraboro subgroup.

- Abdrahamane Sa'adi (1594-1655), son of Mahmud Kati and grandson of Askia Muhammad I,scholar, cadi of Djenné and author of Tarikh al-Sudan, from Songhai Koyraboro subgroup.

- Ahmad Baba al-Timbukti (1556-1627), (culturally and linguistically Songhai, descended from Berber and Songhai ancestors), Teacher, Jurist, Scholar, Arabic, Grammarian of Songhai Empire and Saadi Sultanate, from Songhai Koyraboro subgroup.

- Makhluf al-Balbali( unknown-1533), Islamic scholars of North Africa and West Africa, jurist and teacher in Timbuktu, Kano, Katsina and Marrakesh, from Songhai Belbali subgroup of Tabelbala.

See also

References

- "Africa: Niger – The World Factbook – Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov. 27 April 2021. Retrieved 1 May 2021.

- "Africa: Mali – The World Factbook – Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov. 27 April 2021. Retrieved 1 May 2021.

- "Principaux Indicateurs Socio Demographiques et Economiques (RGPH-4, 2013)" (PDF). Institut National de La Statistique et de L'Analyse Economique, Republique du Benin. 2016. Retrieved 16 November 2022.

- Stoller, Paul (1992), The Cinematic Griot: The Ethnography of Jean Rouch, University of Chicago Press, p. 59 "In this way the true Songhay, after the seventeenth century, is no longer the one of Timbuktu or Gao, but the one farther south near the Anzourou, the Gorouol, on the islands of the river surrounded by rapids" (Rouch 1953, 224), ISBN 9780226775487, retrieved 4 June 2021

- Linguistics and Language Behavior Abstracts: LLBA., Volume 33, Issue 3, 1999, retrieved 14 May 2021

- Etudes de lettres, Faculté des lettres de l'Université de Lausanne, 2002, retrieved 14 May 2021

- Heath, Jeffrey. 1999. A grammar of Koyraboro (Koroboro) Senni: the Songhay of Gao. Köln: Köppe. 402 pp

- "Niger". Ethnologue. Archived from the original on 18 October 2006. Retrieved 4 November 2015.

- Dimmendaal, Gerrit. 2008. Language Ecology and Linguistic Diversity on the African Continent. Language and Linguistics Compass 2(5): 843ff.

- Hama, Boubou (January 1974). L'Empire Songhay : Ses ethnies, ses légendes et ses personnages historiques. FeniXX. ISBN 9782307305088.

- Levtzion & Hopkins 2000, p. 7.

- Levtzion & Hopkins 2000, pp. 27, 378 n4.

- Levtzion & Hopkins 2000, pp. 45, 51, 382 n21.

- https://journals.openedition.org/africanistes/2848

- Hama, Boubou (1967). L'Histoire traditionnelle d'un peuple, les Zarma-Songhay (in French). Présence africaine.

- Hunwick 1999, p. 180 n40.

- Gado, Boubé (1980), Le Zarmatarey, Institut de recherches en sciences humaines, ISBN 9782859210458, retrieved 4 March 2021

- Rouch, Jean (1954), Les Songhay (PDF), retrieved 4 March 2021

- Hunwick 2003, pp. xxxv, 5.

- Bentiya is at 15.349°N 0.760°E

- Moraes Farias 1990, p. 105.

- Kukiya is written as Koûkiya in the French translation.

- Sauvaget, "Épitaphes", 418.

- Lange, Kingdoms, 503

- Lange, Kingdoms, 498–509; Moraes Farias ignoriert die Synchronismen, Inscriptions, 3–8;

- Sauvaget 1950; Hunwick 1980; Moraes Farias 1990; Lange 1991

- Levtzion & Hopkins 2000, p. 1.

- Hunwick 2003, p. xxxviii.

- Hunwick 2003, pp. lxiii–lxiv.

- Levtzion & Hopkins 2000, p. 7; Levtzion 1973, p. 15

- Levtzion & Hopkins 2000, p. 174.

- Insoll 1997.

- Cissé et al. 2013, p. 30

- Insoll 1997, p. 23.

- Levtzion & Hopkins 2000, p. 87.

- Levtzion & Hopkins 2000, p. 113.

- Levtzion & Hopkins 2000, p. 85.

- Kâti 1913, p. 329; Hunwick 1994, p. 265

- Insoll 1997, pp. 4–8.

- A similar list of rulers is given in the Tarikh al-Fattash. Kâti 1913, pp. 331–332

- Levtzion 1973, p. 76.

- Hunwick 2003, p. xxxvi.

- Levtzion & Hopkins 2000, p. 300.

- Hunwick 2003, p. xxxvii.

- Lange 1994, p. 421.

- al-Sadi, translated in Hunwick 1999, p. 10

- Ibn Khaldun, translated in Levtzion & Hopkins 2000, p. 334

- Levtzion 1973, p. 75.

- Kâti 1913, p. 335

- Kâti 1913, p. 334; Hunwick 2003, pp. xxxvi–xxxvii, 7

- Hunwick 2003, p. 7.

- The town of Kukiya is believed to have been near the modern village of Bentiya on the eastern bank of the Niger, north of the Fafa rapids, 134 km south east of Gao. Bentiya is located at 15.349°N 0.760°E

- Kâti 1913, pp. 80, 334

- Hunwick 2003, pp. 333–334, Appendix 2.

- Kâti 1913, pp. 80–81

- "The Story of Africa- BBC World Service". Retrieved 4 November 2013.

- Levtzion 2007, p. 445.

- Historical Dictionary of Niger (in German) (4. ed.), Plymouth: Scarecrow, 1998, pp. 173–174, ISBN 0-7864-0495-7

- Levtzion 2003, p. 165.

- Edmond, Séré de Rivières (1965), Histoire du Niger, p. 73, retrieved 18 April 2021

- http://www.historyfiles.co.uk/KingListsAfrica/AfricaNiger.htm History Files

- UNESCO General History of Africa, Vol. V., pg. 301

- B.A. Ogot (1992), p.307

- J.D. Fage (1975), p.155

- B.A. Ogot (1992), p.315

- Saad, Elias N. (2010). Social History of Timbuktu: The Role of Muslim Scholars and Notables 1400–1900. Cambridge University Press. p. 156. ISBN 978-0521136303.

- J.D. Fage (1975), p.170

- Ivor Wilks, Wa and the Wala: Islam and polity in Northwestern Ghana (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989), p. 1

- Holden, J.J. (1965), The Zabarima conquest of North-West Ghana, Part I, Polish Scientific Publishers, pp. 60–86, ISBN 9788301108724, retrieved 4 March 2023

- Daddieh, Cyril K. (2016). Historical Dictionary of Cote d'Ivoire (The Ivory Coast). Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 426–427. ISBN 978-0-8108-7389-6.

- https://dumas.ccsd.cnrs.fr/dumas-02156244

- https://www.sahistory.org.za/sites/default/files/file%20uploads%20/general_history_africa_iv.pdf pages 193-194

- Hunwick 1999, p. 20.

- Cory, Stephen (2 February 2012). "Judar Pasha". In Akyeampong, Emmanuel K.; Louis Gates, Henry (eds.). Dictionary of African Biography. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195382075.

- https://www.nordsud.info/gbeke-sidi-toure-raconte-lhistoire-de-lempire-de-marabadiassa

- https://www.persee.fr/doc/jafr_0399-0346_1990_num_60_2_2449

- Blench, Roger & Lameen Souag. m.s. Saharan and Songhay form a branch of Nilo-Saharan.

- Seydou Hanafiou, Hamidou. 1995. Eléments de description du kaado d'Ayorou-Goungokore (parler songhay du Niger). (Doctoral dissertation, Université Stendhal (Grenoble 3); 437pp.)

- Southern Songhay Speech Varieties In Niger:A Sociolinguistic Survey of the Zarma, Songhay, Kurtey, Wogo, and Dendi Peoples of Niger (PDF), Byron & Annette Harrison and Michael J. Rueck Summer Institute of Linguistics B.P. 10151, Niamey, Niger Republic, Page 2, 1997, retrieved 23 February 2021

- Shopen, T. & Konaré, M. 1970. "Sonrai Causatives and Passives: Transformational versus Lexical Derivations for Propositional Heads", Studies in African Linguistics 1.211–54. Cited in Dixon, R.M.W. (2000). "A Typology of Causatives: Form, Syntax, and Meaning". In Dixon, R.M.W. & Aikhenvald, Alexendra Y. Changing Valency: Case Studies in Transitivity. Cambridge University Press. pp. 31.

- Tersis, Nicole (1981). Economie d'un système: unités et relations syntaxiques en zarma (Niger). Peeters Publishers. Peeters Publishers. ISBN 9782852971257.

- Bornand, Sandra (2005). Le discours du griot généalogiste chez les Zarma du Niger. Vol. 1. KARTHALA Editions. Karthala. ISBN 9782845866256.

- Journal de la Société des africanistes, Volume 36, France: Société des africanistes, 1966, p. 256, retrieved 21 April 2021

- Zarma, a Songhai language, retrieved 23 February 2021

- Paul Stoller. pp.94-5 in Eye, Mind and Word in Anthropology. L'Homme (1984) Volume 24 Issue 3-4 pp.91-114.

- Idrissa, Abdourahmane; Decalo, Samuel (2012). Historical Dictionary of Niger. Scarecrow Press. pp. 474–476. ISBN 978-0-8108-7090-1.

- Songhai people, Encyclopædia Britannica

- Rubin, Don (1997). The World Encyclopedia of Contemporary Theatre: Africa. Taylor & Francis. p. 212. ISBN 978-0-415-05931-2.

- Hama, Boubou (1967). L'Histoire traditionnelle d'un peuple: les Zarma-Songhay (in French). Paris: Présence Africaine. ISBN 978-2850695513.

- Jean-Pierre Olivier de Sardan (1984). Les sociétés Songhay-Zarma (Niger-Mali): chefs, guerriers, esclaves, paysans. Paris: Karthala. pp. 56–57. ISBN 978-2-86537-106-8.

- Tamari, Tal (1991). "The Development of Caste Systems in West Africa". The Journal of African History. Cambridge University Press. 32 (2): 221–250. doi:10.1017/s0021853700025718. JSTOR 182616. S2CID 162509491., Quote: "[Castes] are found among the Soninke, the various Manding-speaking populations, the Wolof, Tukulor, Senufo, Minianka, Dogon, Songhay, and most Fulani, Moorish and Tuareg populations".

- I. Diawara (1988), Cultures nigériennes et éducation: Domaine Zarma-Songhay et Hausa, Présence Africaine, Nouvelle série, number 148 (4e TRIMESTRE 1988), pages 9–19 (in French)

- Haour, Anne (2013). Outsiders and Strangers: An Archaeology of Liminality in West Africa. Oxford University Press. pp. 95–97, 100–101, 90–114. ISBN 978-0-19-969774-8.

- Quigley, Declan (2005). The character of kingship. Berg. pp. 20, 49–50, 115–117, 121–134. ISBN 978-1-84520-290-3.

- Hall, Bruce S. (2011). A History of Race in Muslim West Africa, 1600–1960. Cambridge University Press. pp. 15–18, 71–73, 245–248. ISBN 978-1-139-49908-8.

- Shoup, John A. (2011). Ethnic Groups of Africa and the Middle East: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 265–266. ISBN 978-1-59884-362-0.

- An Introduction to the Zarma Language (PDF), Peace Corps/Niger, 2006, p. 3, retrieved 22 December 2021

- Songhai people Encyclopædia Britannica

- Smith, Bonnie G. (2008). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Women in World History. Oxford University Press. pp. 503–504. ISBN 978-0-19-514890-9.

- Tal Tamari (1998), Les castes de l'Afrique occidentale: Artisans et musiciens endogames, Nanterre: Société d’ethnologie, ISBN 978-2901161509 (in French)

Primary sources

- Ibn Khaldun, Kitāb al-ʿIbar wa-dīwān al-mubtadaʾ wa-l-khabar fī ayyām al-ʿarab wa-ʾl-ʿajam wa-ʾl-barbar, translated in Levtzion & Hopkins 2000

- al-Sadi, Taʾrīkh al-Sūdān, translated in Hunwick 1999

Bibliography

- Hunwick, John (1980). "Gao and the Almoravids: a hypothesis". In Swartz, B.; Dumett, R. (eds.). West African Culture Dynamics. The Hague. pp. 413–430. ISBN 90-279-7920-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Hunwick, John (1994), "Gao and the Almoravids revisited: ethnicity, political change and the limits of interpretation", Journal of African History, 35 (2): 251–273, doi:10.1017/s0021853700026426, JSTOR 183219, S2CID 153794361.

- Hunwick, John O. (1999), Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire: Al-Sadi's Tarikh al-Sudan down to 1613 and other contemporary documents, Leiden: Brill, ISBN 90-04-11207-3.

- Hunwick, John O. (2003), Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire: Al-Sadi's Tarikh al-Sudan down to 1613 and other contemporary documents, Leiden: Brill, ISBN 9789004128224.

- Insoll, Timothy (1997). "Iron age Gao: an archaeological contribution". Journal of African History. 38 (1): 1–30. doi:10.1017/s0021853796006822. JSTOR 182944. S2CID 163151474.

- Kâti, Mahmoûd Kâti ben el-Hâdj el-Motaouakkel (1913), Tarikh el-fettach ou Chronique du chercheur, pour servir à l'histoire des villes, des armées et des principaux personnages du Tekrour (in French), Houdas, O., Delafosse, M. ed. and trans., Paris: Ernest Leroux. Also available from Aluka but requires subscription.

- Lange, Dierk (1991). "Les rois de Gao-Sané et les Almoravides". Journal of African History (in French). 32 (2): 251–275. doi:10.1017/s002185370002572x. JSTOR 182617. S2CID 162674956.

- Lange, Dierk (1994), "From Mande to Songhay: Towards a political and ethnic history of medieval Gao", Journal of African History, 35 (2): 275–301, doi:10.1017/s0021853700026438, JSTOR 183220, S2CID 153657364.

- Moraes Farias, Paulo F. de (1990), "The oldest extant writing of West Africa: medieval epigraphs from Essuk, Saney, and Egef-n-Tawaqqast (Mali)", Journal des Africanistes, 60 (2): 65–113, doi:10.3406/jafr.1990.2452. Link is to a scan on the Persée database that omits some photographs of the epigraphs.

- Levtzion, Nehemia (1973), Ancient Ghana and Mali, London: Methuen, ISBN 0-8419-0431-6.

- Levtzion, Nehemia; Hopkins, John F.P., eds. (2000), Corpus of Early Arabic Sources for West Africa, New York, NY: Marcus Weiner Press, ISBN 1-55876-241-8.

- Sauvaget, Jean (1950). "Les épitaphes royales de Gao". Bulletin de l'IFAN. series B. 12: 418–440.