Solen glimmar blank och trind

Solen glimmar blank och trind (The sun gleams smooth and round) is Epistle No. 48 in the Swedish poet and performer Carl Michael Bellman's 1790 song collection, Fredman's Epistles. The Epistle is subtitled "Hvaruti afmålas Ulla Winblads hemresa från Hessingen i Mälaren en sommarmorgon 1769" ("In which is depicted Ulla Winblad's journey home from Hessingen"). One of his best-known and best-loved works, it depicts an early morning on Lake Mälaren, as the Rococo muse Ulla Winblad sails back home to Stockholm after a night spent partying on the lake. The composition is one of Bellman's two Bacchanalian lake-journeys, along with epistle 25 ("Blåsen nu alla"), representing a venture into a social realism style.

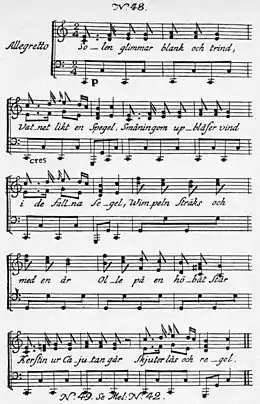

| "Solen glimmar blank och trind" | |

|---|---|

| Art song | |

First page of sheet music | |

| English | The sun gleams smooth and round |

| Written | February 1772 |

| Text | poem by Carl Michael Bellman |

| Language | Swedish |

| Melody | French, used by Antoine de Bourbon and others |

| Published | 1790 in Fredman's Epistles |

| Scoring | voice and cittern |

Places along the route can be identified from Bellman's descriptions. The work has been called a masterpiece, with its freshness compared to Elias Martin's paintings, its detail to William Hogarth's, its delicacy to Watteau's, building up "an incomparable panorama" of 18th century Stockholm.[1] The Epistle, alone among Bellman's works, is often sung in Swedish schools.

Context

Carl Michael Bellman is a central figure in the Swedish ballad tradition and a powerful influence in Swedish music, known for his 1790 Fredman's Epistles and his 1791 Fredman's Songs.[2] A solo entertainer, he played the cittern, accompanying himself as he performed his songs at the royal court.[3][4][5]

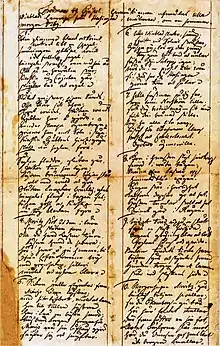

Jean Fredman (1712 or 1713–1767) was a real watchmaker of Bellman's Stockholm. The fictional Fredman, alive after 1767, but without employment, is the supposed narrator in Bellman's epistles and songs.[6] The epistles, written and performed in different styles, from drinking songs and laments to pastorales, paint a complex picture of the life of the city during the 18th century. A frequent theme is the demimonde, with Fredman's cheerfully drunk Order of Bacchus,[7] a loose company of ragged men who favour strong drink and prostitutes. At the same time as depicting this realist side of life, Bellman creates a rococo picture, full of classical allusion, following the French post-Baroque poets. The women, including the beautiful Ulla Winblad, are "nymphs", while Neptune's festive troop of followers and sea-creatures sport in Stockholm's waters.[8] The juxtaposition of elegant and low life is humorous, sometimes burlesque, but always graceful and sympathetic.[3][9] The songs are "most ingeniously" set to their music, which is nearly always borrowed and skilfully adapted.[10] Bellman wrote the first draft of Epistle 48 early in 1772, apparently while at work, as it is penned on a sheet of ready-lined record paper of his employer the General Directorate of Customs.[11]

Song

Music

The song is in the key of C, in 2

4 time. It has 21 verses, each consisting of eight lines.[12][13] The rhyming pattern is ABAB-CCCB; the song was written in February 1772.[1][14] It has a "gay dancing melody", which along with the poem gives the listener[1]

an irresistible impression of being himself present at the song's conception; seems to catch the dashing rhythm of the vessel as it plunges through the waves, to be listening to the voice of the poet where he sits in the stern, improvising his stanza out of the raw materials of the passing moment.

The melody was a favourite of Bellman's, and is of French origin, where it had been used by Antoine de Bourbon.[15] It is found in Joseph de La Font's 1714 opéra-ballet Fêtes de Thalie, the music composed by Jean-Joseph Mouret under the name of "Le Cotillon". This may not have been where Bellman obtained the melody, as it was, the musicologist James Massengale writes, evidently a popular tune at that time, known by many different names ("timbres"). Bellman knew it as "Si le roy m'avoit donné", and set his song "Uppå vattnets lugna våg" in the 1783 edition of Bacchi Tempel, and his poem "Ur en tunn och ljusblå sky", to the same tune.[16]

Lyrics

The Epistle paints a charming picture of an early morning on Lake Mälaren, as the Rococo muse Ulla Winblad sails back home to Stockholm. The song brings in Movitz the cellist, another of Bellman's stock characters in Fredman's Epistles, based on one of his friends.[1]

The song tells the story of a boat on the way home after a night out on the island-studded lake. In the boat are the peasant girl Marjo, a tub of butter on her knees, with a cargo of the birch-sprigs that Stockholmers used to decorate their town with as a sign of returning spring, milk, and lambs; and her father, puffing his pipe self-importantly at the helm. It begins:[1][2]

| Swedish | Prose translation | Hendrik Willem van Loon, 1939[17] | Paul Britten Austin's verse, 1977[18] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solen glimmar blank och trind, Vattnet likt en spegel; Småningom upblåser vind I de fallna segel; Vimpeln sträcks, och med en år Olle på en Höbåt står; Kerstin ur Kajutan går, Skjuter lås och regel. |

The sun gleams smooth and round, Water like a mirror; Gradually the wind blows up In the fallen sails; The pennant stretches, and with an oar Olle stands on a hayboat; Kerstin from the cabin steps, Locks and bolts the door. |

Sunlight gleaming, bright and gay, On the rippling water dances, As our ship with fine display, Proud and loftily advances. Flags unfurl'd, and with an oar, Olle heads the boat from shore; Kerstin from the cabin door, Shoreward casts her[lower-alpha 1] farewell glances. |

Now the sun gleams in the sky, Mirror'd in the water; Early breezes by and by Fill the mains'l tauter. On a hayboat, with an oar Olle shoves off from the shore. Who's that in the cabin door? Kerstin, skipper's daughter! |

Places mentioned

The song is descriptively subtitled "Hvaruti afmålas Ulla Winblads hemresa från Hessingen i Mälaren en sommarmorgon 1769" ("In which is depicted Ulla Winblad's journey home from Hessingen in Lake Mälaren").[2] A series of places that can be seen from that waterway are mentioned in the text:[19]

| Verse | Mention | Place | Image |

|---|---|---|---|

| Title | Ulla Winblads hemresa från Hessingen i Mälaren (Ulla Winblad's journey home from Hessingen in Lake Mälaren) | Essingen Islands in Lake Mälaren, to the west of Stockholm |  View of Stockholm from Stora Essingen. Painting by Ernfried Wahlqvist, 1890 |

| 4 | Ifrån Lofön komma vi (We're from Lofön) | Lovön, an island in Lake Mälaren |  Traditional house on Lovön |

| 10 | Ser du Ekensberg? Gutår! (Can you see Ekensberg? Cheers!) | Ekensbergs värdshus, a well-frequented sailors' tavern on the south bank of Lake Mälaren, opposite Stora Essingen island |  Ekensberg tavern. Woodcut, 19th century |

| 12 | På den klippan, där vid strand Sjelf Chinesen prålar (On the cliff, there by the shore The Chinese [figures] themselves show off) | The Marieberg porcelain factory on Kungsholmen island |  Marieberg porcelain factory around 1768. Painting by Jacob Philipp Hackert |

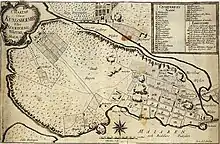

| 13 | Fönstren glittra, kännen J Ej Salpetersjuderi? En gång, Ulla – raljeri! – Palten dit dig leder. (The windows are shining, don't you know the Saltpeter factory? One day, Ulla – I'm joking! – The bailiffs will take you there.) | The Salpetersjuderi, a noisome workplace on Kungsholmen island that boiled up offal, urine and lime to make saltpeter, an ingredient of gunpowder |  Kungsholmen in 1754, with the Saltpeter works above the compass rose. Map by O. J. Gjöding |

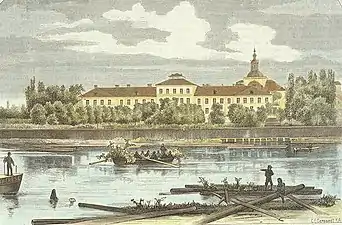

| 14 | Lazari palats (Lazarus's palace) | The Serafimerlasarettet, a hospital on Kungsholmen island, alluding to the Biblical Lazarus, Luke 16:20. |  Serafimerlasarettet hospital on Kungsholmen in 1868 |

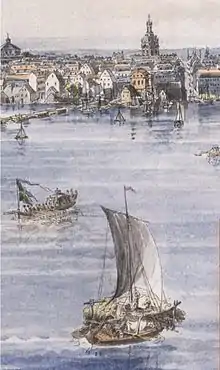

| 16 | Ren syns Skinnarviken, Med dess Kojor och Castell, Branta berg och diken; (Skinnarviken can be seen, With its huts and fort, Steep hills and ditches;) | Skinnarviken, then a small bay on Stockholm's Södermalm island, below its highest point, Skinnarviksberget, facing Lake Mälaren | .jpg.webp) View across Skinnarviken to central Stockholm. Engraving with watercolour by Johan Fredrik Martin, c. 1790 |

Reception and legacy

Bellman's biographer, the translator Paul Britten Austin calls the poem a masterpiece and "one of Bellman's greatest. At a stroke he created in Swedish poetry a new vision of the natural and urban scene. Fresh as Martin's. Detailed as Hogarth's. Frail and ethereal as Watteau's." While each verse paints a "finely etched picture", he argues that all together they "build up to an incomparable panorama of that eighteenth-century Stockholm which meets us in Elias Martin's canvasses".[1] Britten Austin writes that[1]

No one who has ever risen on an early Swedish summer morning to see the sun shining from a clear sky on the placid water and has heard or read this song, with its breezy familiar air, can ever forget it.

Britten Austin explains: "Everything occurs with apparent haphazardness. Yet each stanza is a little picture, framed by its melody. We remember it all, seem to have lived through it, like a morning in our own lives."[1]

The scholar of literature Lars Lönnroth writes that Bellman transformed song genres including elegy and pastorales into social reportage, and that he achieved this also in his two Bacchanalian lake-journeys, epistles 25 ("Blåsen nu alla") and 48. The two are, he notes, extremely unlike in style, narrative technique, and Fredman's role in the description. Whereas epistle 25 portrays Ulla Winblad as the goddess Venus, and speaks of Neptune's court with classical mythological appurtenances like zephyrs, water-nymphs, and "all the might of Paphos" (the birthplace of Venus), Solen glimmar starts entirely naturalistically.[14] Lönnroth notes that the subtitle explicitly states that the song paints a landscape, with the word "avmålas", "is depicted"; that the verses offer small "snapshots" of nature and country life; how Ulla is here no muse but a flesh-and-blood woman; and how the text of verse 12 actually speaks of painting a landscape.[14] He writes that in verse 4, the factual narrative is linked to Fredman's company with an invitation to Movitz to blow his horn, Bellman's usual signal that the scene is changing; in epistle 25, the invitation to blow introduces Neptune and his entourage. In Solen glimmar, he ends the voyage with the arrival of Fredman and company at an inn where the seasick Ulla drops her skirt and climbs into bed; she is accompanied by Norström, and followed by Movitz with his bassoon, calling out to Norström that "The woman belongs to all of us".[14] Lönnroth comments that the two epistles move the Fredman opus towards greater realism, but that this only adds to Bellman's repertoire of biblical parody and mythological rhetoric.[14]

Carina Burman comments in her biography of Bellman that Bellman had a tendency to make humorous remarks about women's bodily functions rather than sex in his songs, as with his "[Ulla] Kröp inunder / Med ett dunder / Vände sig och log" ([Ulla] crept under [the bedclothes] / with a thunder / turned over and grinned) in Epistle 36. The first version of Epistle 48 similarly had the line "Tuppen gol och Kerstin fes" (The cockerel crowed and Kerstin farted), later replaced by "Tuppen gol så sträf och hes" (The cockerel crowed so rough and hoarse). Burman remarks that from a purely literary point of view, the change was undeniably an improvement.[20]

Epistle 48 was one of the 20 most popular songs on Swedish school radio between 1934 and 1969, and it remained one of the pieces most often sung by Swedish teachers in the 1970s. In both cases, the Epistle was the only Bellman composition listed.[21]

Epistle 48 has been recorded by Cornelis Vreeswijk on his 1971 album Spring mot Ulla, spring! Cornelis sjunger Bellman;[22] by Evert Taube on his 1976 album Evert Taube Sjunger Och Berättar Om Carl Michael Bellman; and by Mikael Samuelson on his 1988 album Mikael Samuelson Sjunger Fredmans Epistlar.[23] The 1993 festschrift Fin(s) de Siècle in Scandinavian Perspective: Studies in Honor of Harald S. Naess is introduced with a seven-stanza song about Naess, set to the tune of the Epistle, and with some of its words, as in "Solen glimmar kring hans färd" (The sun gleams around his journey).[24]

Notes

- Van Loon has "his".

References

- Britten Austin 1967, pp. 103–105

- Bellman 1790.

- "Carl Michael Bellmans liv och verk. En minibiografi (The Life and Works of Carl Michael Bellman. A Short Biography)" (in Swedish). Bellman Society. Archived from the original on 10 August 2015. Retrieved 25 April 2015.

- "Bellman in Mariefred". The Royal Palaces [of Sweden]. Archived from the original on 21 June 2022. Retrieved 19 September 2022.

- Johnson, Anna (1989). "Stockholm in the Gustavian Era". In Zaslaw, Neal (ed.). The Classical Era: from the 1740s to the end of the 18th century. Macmillan. pp. 327–349. ISBN 978-0131369207.

- Britten Austin 1967, pp. 60–61.

- Britten Austin 1967, p. 39.

- Britten Austin 1967, pp. 81–83, 108.

- Britten Austin 1967, pp. 71–72 "In a tissue of dramatic antitheses—furious realism and graceful elegance, details of low-life and mythological embellishments, emotional immediacy and ironic detachment, humour and melancholy—the poet presents what might be called a fragmentary chronicle of the seedy fringe of Stockholm life in the 'sixties.".

- Britten Austin 1967, p. 63.

- Burman 2019, p. 168.

- Hassler & Dahl 1989, pp. 124–129.

- Kleveland & Ehrén 1984, p. 46–49, 117.

- Lönnroth 2005, pp. 207–213.

- "Epistel N:o 48". Bellman.net. Retrieved 17 March 2016.

- Massengale 1979, pp. 185–188.

- Van Loon & Castagnetta 1939, pp. 52–53.

- Britten Austin 1977, p. 95.

- "N:o 48 Fredmans Epistel (annotations linked to text)". Bellman.net. Retrieved 15 September 2021.

- Burman 2019, pp. 476–477.

- Kjellander, Eva (2005). "Sitter ekorren fortfarande i granen? Sångrepertoar i grundskolan nu och då" [Is the squirrel still in the tree? Singing repertoire in primary school now and then] (PDF) (in Swedish). Växjö University (Musicology thesis). pp. 16, 41, 56. Retrieved 15 September 2021.

- Hassler & Dahl 1989, p. 280.

- Hassler & Dahl 1989, p. 277.

- Ingwersen, Faith; Norseng, Mary Kay, eds. (1993). Fin(s) de Siècle in Scandinavian Perspective: Studies in Honor of Harald S. Naess. Boydell & Brewer. pp. 2–3. ISBN 9781879751248.

Sources

- Bellman, Carl Michael (1790). Fredmans epistlar. Stockholm: By Royal Privilege.

- Britten Austin, Paul (1967). The Life and Songs of Carl Michael Bellman: Genius of the Swedish Rococo. New York: Allhem, Malmö American-Scandinavian Foundation. ISBN 978-3-932759-00-0.

- Britten Austin, Paul (1977). Fredman's Epistles and Songs. Stockholm: Reuter and Reuter. OCLC 5059758.

- Burman, Carina (2019). Bellman. Biografin [Bellman: The Biography] (in Swedish). Stockholm: Albert Bonniers Förlag. ISBN 978-9100141790.

- Hassler, Göran; Dahl, Peter (illus.) (1989). Bellman – en antologi [Bellman – an anthology]. En bok för alla. ISBN 91-7448-742-6. (contains the most popular Epistles and Songs, in Swedish, with sheet music)

- Kleveland, Åse; Ehrén, Svenolov (illus.) (1984). Fredmans epistlar & sånger [The songs and epistles of Fredman]. Stockholm: Informationsförlaget. ISBN 91-7736-059-1. (with facsimiles of sheet music from first editions in 1790, 1791)

- Lönnroth, Lars (2005). Ljuva karneval! : om Carl Michael Bellmans diktning [Lovely Carnival! : about Carl Michael Bellman's Verse]. Stockholm: Albert Bonniers Förlag. ISBN 978-91-0-057245-7. OCLC 61881374.

- Massengale, James Rhea (1979). The Musical-Poetic Method of Carl Michael Bellman. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell International. ISBN 91-554-0849-4.

- Van Loon, Hendrik Willem; Castagnetta, Grace (1939). The Last of the Troubadours. New York: Simon & Schuster.

External links

- Text of Epistle 48 at Bellman.net

- English translation by Eva Toller