Energy in Indonesia

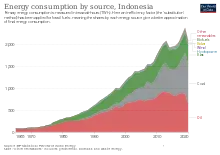

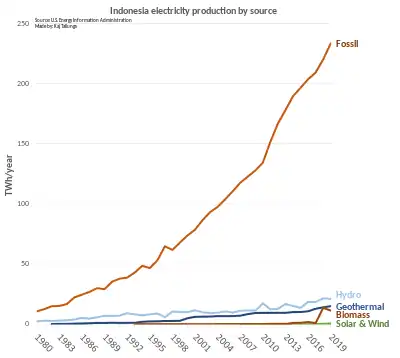

In 2019, the total energy production in Indonesia is 450.79 Mtoe, with a total primary energy supply is 231.14 Mtoe and electricity final consumption is 263.32 TWh.[1] Energy use in Indonesia has been long dominated by fossil resources. Once a major oil exporter in the world and joined OPEC in 1962, the country has since become a net oil importer despite still joined OPEC until 2016, making it the only net oil importer member in the organization.[2] Indonesia is also the fourth-largest biggest coal producer and one of the biggest coal exporter in the world, with 24,910 million tons of proven coal reserves as of 2016, making it the 11th country with the most coal reserves in the world.[3][1] In addition, Indonesia has abundant renewable energy potential, reaching almost 417,8 gigawatt (GW) which consisted of solar, wind, hydro, geothermal energy, ocean current, and bioenergy, although only 2,5% have been utilized.[4][5] Furthermore, Indonesia along with Malaysia, have two-thirds of ASEAN's gas reserves with total annual gas production of more than 200 billion cubic meters in 2016.[6]

The Government of Indonesia has outlined several commitments to increase clean energy use and reduce greenhouse gas emissions, among others by issuing the National Energy General Plan (RUEN) in 2017 and joining the Paris Agreement. In the RUEN, Indonesia targets New and Renewable Energy to reach 23% of the total energy mix by 2025 and 31% by 2050.[7] The country also commits to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions by 29% by 2030 against a business-as-usual baseline scenario, and up to 41% by international support.[8]

Indonesia has several high-profile renewable projects, such as the wind farm 75 MW in Sidenreng Rappang Regency, another wind farm 72 MW in Jeneponto Regency, and Cirata Floating Solar Power Plant in West Java with a capacity of 145 MW which will become the largest Floating Solar Power Plant in Southeast Asia.[9]

Overview

| Population (million) |

Primary energy (TWh) |

Production (TWh) |

Export (TWh) |

Electricity (TWh) |

CO2-emission (Mt) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | 217.6 | 2,024 | 3,001 | 973 | 104 | 336 |

| 2007 | 225.6 | 2,217 | 3,851 | 1,623 | 127 | 377 |

| 2008 | 228.3 | 2,311 | 4,035 | 1,714 | 134 | 385 |

| 2009 | 230.0 | 2,349 | 4,092 | 1,787 | 140 | 376 |

| 2010 | 239.9 | 2,417 | 4,436 | 2,007 | 154 | 411 |

| 2012 | 242.3 | 2,431 | 4,589 | 2,149 | 166 | 426 |

| 2012R | 246.9 | 2,484 | 5,120 | 2,631 | 181 | 435 |

| 2013 | 250.0 | 2,485 | 5,350 | 2,858 | 198 | 425 |

| Change 2004-10 | 10.2% | 19.4% | 48% | 106% | 48% | 22% |

| Mtoe = 11.63 TWh

2012R = CO2 calculation criteria changed, numbers updated | ||||||

According to the IEA, energy production increased 34% and export 76% from 2004 to 2008 in Indonesia. In 2017, Indonesia had 52,859 MW of installed electrical capacity, 36,892 MW of which were on the Java–Bali grid.[11] In 2022, Indonesia had an electrical capacity of 81.2 GW with a projected capacity of 85.1 GW for 2023.[12]

Energy by sources

Coal

Indonesia has a lot of medium and low-quality thermal coal, and there are price caps on supplies for domestic power stations, which discourages other types of electricity generation.[13] At current rates of production, Indonesia's coal reserves are expected to last for over 80 years. In 2009 Indonesia was the world's second top coal exporter, sending coal to China, India, Japan, Italy and other countries. Kalimantan (Borneo) and South Sumatra are the centres of coal mining. In recent years, production in Indonesia has been rising rapidly, from just over 200 mill tons in 2007 to over 400 mill tons in 2013. In 2013, the chair of the Indonesian Coal Mining Association said the production in 2014 may reach 450 mill tons.[14]

The Indonesian coal industry is rather fragmented. Output is supplied by a few large producers and a large number of small firms. Large firms in the industry include the following:[15]

- PT Bumi Resources (the controlling shareholder of large coal firms PT Kaltim Prima Coal and PT Arutmin Indonesia)

- PT Adaro Energy

- PT Kideco Jaya Agung

- PT Indo Tambangraya Megah

- PT Berau Coal

- PT Tambang Batubara Bukit Asam (state-owned)

Coal production poses risks for deforestation in Kalimantan. According to one Greenpeace report, a coal plant in Indonesia has decreased the fishing catches and increased the respiratory-related diseases.[16]

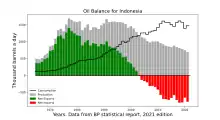

Oil

Oil is a major sector in the Indonesian economy. During the 1980s, Indonesia was a significant oil-exporting country. Since 2000, domestic consumption has continued to rise while production has been falling, so in recent years Indonesia has begun importing increasing amounts of oil. Within Indonesia, there are considerable amounts of oil in Sumatra, Borneo, Java, and West Papua Province. There are said to be around 60 basins across the country, only 22 of which have been explored and exploited.[17] Main oil fields in Indonesia include the following:

- Minas. The Minas field, in Riau, Sumatra, operated by the US-based firm Chevron Pacific Indonesia, is the largest oil block in Indonesia.[18] Output from the field is around 20-25% of current annual oil production in Indonesia.

- Duri. The Duri field, in Bengkalis Regency, Riau, Sumatra, is operated by the US-based firm Chevron Pacific Indonesia.[19]

- Rokan. The Rokan field, Riau, Sumatra, operated by Chevron Pacific Indonesia, is a recently developed large field in the Rokan Hilir Regency.

- Cepu. The Cepu field, operated by Mobil Cepu Ltd which is a subsidiary of US-based Exxon Mobil, is on the border of Central and East Java near the town of Tuban. The field was discovered in March 2001 and is estimated to have proven reserves of 600 million barrels of oil and 1.7 trillion cu feet of gas. Development of the field has been subject to on-going discussions between the operators and the Indonesian government.[20][21] Output is forecast to rise from around 20,000 bpd in early 2012 to around 165,000 bpd in late 2014.[22]

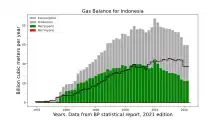

Gas

There is growing recognition in Indonesia that the gas sector has considerable development potential.[23] In principle, the Indonesian government is supporting moves to give increasing priority to investment in natural gas. In practice, private sector investors, especially foreign investors, have been reluctant to invest because many of the problems that are holding back investment in the oil sector also affect investment in gas. In mid-2013, main potential gas fields in Indonesia were believed to include the following:

- Mahakam. The Mahakam block in East Kalimantan, under the management of Total E&P Indonesie with participation from the Japanese oil and gas firm Inpex, provides around 30% of Indonesia's natural gas output. In mid 2013 the field was reported to be producing around 1.7 billion cu ft (48 million m3) per day of gas as well as 67,000 barrels (10,700 m3) of condensate. At the time discussions were underway about the details of the future management of the block involving a proposal that Pertamina take over all or part of the management of the block.[24] In October 2013 it was reported that Total E&P Indonesie had announced that it would stop exploration for new projects at the field.[25] In 2015 the Energy and Resources Minister issued a regulation stipulating that the management of the block would be transferred from Total E&P Indonesie and Inpex, which had managed the field for over 50 years since 1966, to Pertamina.[26] In late 2017, it was announced that Pertamina Hulu Indonesia, a subsidiary of Pertamina, would take over management of the block on 1 January 2018.

- Tangguh. The Tangguh field in Bintuni Bay in West Papua Province operated by BP (British Petroleum) is estimated to have proven gas reserves of 4.4 trillion cu ft (120 billion m3). It is hoped that annual output of the field in the near future might reach 7.6 million tons of liquefied natural gas.[27]

- Arun. The Arun field in Aceh has been operated by ExxonMobil since the 1970s. The reserves at the field are now largely depleted so production is now slowly being phased out. At the peak, the Arun field produced around 3.4 million cu ft (96 thousand m3) of gas per day (1994) and about 130,000 of condensate per day (1989). ExxonMobil affiliates also operate the nearby South Lhoksukon A and D fields as well as the North Sumatra offshore gas field.[28] In September 2015, ExxonMobil Indonesia sold its assets in Aceh to Pertamina. The sale included the divestment by ExxonMobil of its assets (100%) in the North Sumatra Offshore block, its interests (100%) in B block, and its stake (30%) in the PT Arun Natural Gas Liquefaction (NGL) plant. Following the completion of the deal, Pertamina will have an 85% stake in the Arun NGL plant.[29]

- East Natuna. The East Natuna gas field (formerly known as Natuna D-Alpha) in the Natuna Islands in the South China Sea is believed to be one of the biggest gas reserves in Southeast Asia. It is estimated to have proven reserves of 46 trillion cu ft (1.3 trillion m3) of gas. The aim is to begin expanded production in 2020 with production rising to 4,000 million cu ft/d (110 million m3/d) sustained for perhaps 20 years.[30]

- Banyu Urip. The Banyu Urip field, a major field for Indonesia, is in the Cepu block in Bojonegoro Regency in East Java. Interests in the block are held by Pertamina (45%) through its subsidiary PT Pertamina EP Cepu and ExxonMobil Cepu Limited (45%) which is a subsidiary of ExxonMobil Corporation. ExxonMobil is the operator of the block.[31]

- Masela. The Masela field, currently (early 2016) under consideration for development by the Indonesian Government, is situated to the east of Timor Island, roughly halfway between Timor and Darwin in Australia. The main investors in the field are currently (early 2016) Inpex and Shell who hold stakes of 65% and 35% respectively. The field, if developed, is likely to become the biggest deepwater gas project in Indonesia, involving an estimated investment of between $14–19 billion. Over 10 trillion cu ft (280 billion m3) of gas are said to exist in the block.[32] However, development of the field is being delayed over uncertainty as to whether the field might be operated through an offshore or onshore processing facility. In March 2016, after a row between his ministers,[33] President Jokowi decreed that the processing facility should be onshore.[34] This change of plans will involve the investors in greatly increased costs and will delay the start of the project. It was proposed that they submit revised Plans of Development (POD) to the Indonesian Government.[35]

- See also List of gas fields in Indonesia.

Shale

There is potential for tight oil and shale gas in northern Sumatra and eastern Kalimantan.[36] There are estimated to be 46 trillion cu ft (1.3 trillion m3) of shale gas and 7.9 billion barrels (1.26×109 m3) of shale oil which could be recovered with existing technologies.[37] Pertamina has taken the lead in using hydraulic fracturing to explore for shale gas in northern Sumatra. Chevron Pacific Indonesia and NuEnergy Gas are also pioneers in using fracking in existing oil fields and in new exploration. Environmental concerns and a government-imposed cap on oil prices present barriers to full development of the substantial shale deposits in the country.[38] Sulawesi, Seram, Buru, Papua in eastern Indonesia have shales that were deposited in marine environments which may be more brittle and thus more suitable for fracking than the source rocks in western Indonesia which have higher clay content.[37]

Coal bed methane

With 453 trillion cu ft (12.8 trillion m3) of coal bed methane (CBM) reserve mainly in Kalimantan and Sumatra, Indonesia has potential to redraft its energy charts as United States with its shale gas. With low enthusiasm to develop CBM project, partly in relation to environmental concern regarding emissions of greenhouse gases and contamination of water in the extraction process, the government targeted 8.9 million cu ft (250 thousand m3) per day at standard pressure for 2015.[39]

Renewable energy sources

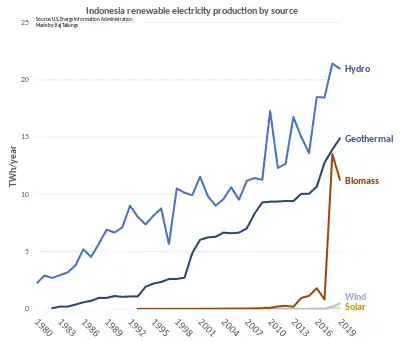

Indonesia has set a target of 23% and 31% of its energy to come from renewable sources by 2025 and 2050 respectively.[40] In 2020, Renewable in Indonesia has contributed 11.2% to the national energy mix, with hydro and geothermal power plants making up the largest share.[41] Despite the substantial renewable energy potential, Indonesia is still struggling to achieve its renewable target. The lack of adequate regulation supports to attract the private sector and the regulation inconsistency are often cited among the main reasons for the problems. One policy requires private investors to transfer their projects to PLN (the sole electricity off-taker in the country) at the end of agreement periods, which, combined with the fact that the Minister for Energy and Mineral Resources sets the consumer price of energy, has led to concern about return on investment.

Another issue is related to financing, as to achieve the 23% target, Indonesia needs an investment of about US$154 billion. The state is unable to allocate this huge amount meanwhile there is reluctance from both potential investors and lending banks to get involved.[42] There is also a critical challenge related to cost. The initial investment of the renewable projects is still high and as the electricity price has to be below the Region Generation Cost (BPP) (which is already low enough in some major areas), it makes the project unattractive. Indonesia also has large coal reserves and is one of the world's largest net exporters of coal, making it less urgent to develop renewable-based power plants compared to countries that depend on coal imports.[43]

It is recommended that the country removes subsidies for fossil fuels, establishes a ministry of renewable energy, improves grid management, mobilizes domestic resources to support renewable energy, and facilitates market entry for international investors.[44] Continued reliance on fossil fuels by Indonesia may leave its coal assets stranded and result in significant investments lost as renewable energy is rapidly becoming cost-efficient worldwide.[45]

In February 2020, it was announced that the People's Consultative Assembly is preparing its first renewable energy bill.[46]

Biomass

An estimated 55% of Indonesia's population, 128 million people, primarily rely upon traditional biomass (mainly wood) for cooking.[47] Reliance on this source of energy has the disadvantage that poor people in rural areas have little alternative but to collect timber from forests, and often cut down trees, to collect wood for cooking.

A pilot project of Palm Oil Mill Effluent (POME) Power Generator with the capacity of 1 Megawatt has been inaugurated in September 2014.[48]

Hydroelectricity

Indonesia has 75 GW of hydro potential, although only around 5 GW has been utilized.[41][49] Currently, only 34GW of Indonesia's total hydro potential can feasibly be utilized due to high development costs in certain areas.[50] Indonesia also set a target of 2 GW installed capacity in hydroelectricity, including 0.43 GW micro-hydro, by 2025.[51] Indonesia has a potential of around 459.91 MW for micro hydropower developments, with only 4.54% of it being currently exploited.[52]

Geothermal energy

Indonesia uses some geothermal energy.[53] According to the Renewable Energy Policy Network's Renewables 2013 Global Status Report, Indonesia has the third largest installed generating capacity in the world. With 1.3 GW installed capacity, Indonesia trails only the United States (3.4 GW) and the Philippines (1.9 GW), ahead of Mexico (1.0 GW), Italy (0.9 GW), New Zealand (0.8 GW), Iceland (0.7 GW), and Japan (0.5 GW).[54] The current official policy is to encourage the increased use of geothermal energy for electricity production. Geothermal sites in Indonesia include the Wayang Windu Geothermal Power Station and the Kamojang plant, both in West Java.

The development of the sector has been proceeding rather more slowly than hoped. Expansion appears to be held up by a range of technical, economic, and policy issues which have attracted considerable comment in Indonesia. However, it has proved difficult to formulate policies to respond to the problems.[55][56][57]

Two new plants are slated to open in 2020, at Dieng Volcanic Complex in Central Java and at Mount Patuha in West Java.[58]

Wind power

On average, low wind speeds mean that for many locations there is limited scope for large-scale energy generation from wind in Indonesia. Only small (<10 kW) and medium (<100 kW) generators are feasible.[59] For Sumba Island in East Nusa Tengarra (NTT), according to NREL, three separate technical assessments have found that "Sumba’s wind resources could be strong enough to be economically viable, with the highest estimated wind speeds ranging from 6.5 m/s to 8.2 m/s on an annual average basis."[60] A very small amount of (off-grid) electricity is generated using wind power. For example, a small plant was established at Pandanmino, a small village on the south coast of Java in Bantul Regency, Yogyakarta Province, in 2011. However, it was established as an experimental plant and it is not clear whether funding for long-term maintenance will be available.[61]

In 2018, Indonesia installed its first wind farm, the 75 MW Sidrap, in Sidenreng Rappang Regency, South Sulawesi, which is the biggest wind farm in Southeast Asia.[62][63] In 2019, Indonesia installed another wind farm with a capacity of 72 MW, in Jeneponto Regency, South Sulawesi.[62]

Solar power

The Indonesian solar PV sector is relatively underdeveloped but has significant potential, up to 207 GW with utilization in the country is less than 1%.[64] However, a lack of consistent and supportive policies, the absence of attractive tariff and incentives, as well as concerns about on-grid readiness pose barriers to the rapid installation of solar power in Indonesia, including in rural areas.[65]

Tidal Power

With over 17,000 islands within its borders, Indonesia has great potential for tidal power development. The Alas Strait, a 50km stretch of ocean between Lombok and Sumbawa Island, alone could potentially yield as high as 640GWh of energy annually from tidal power.[66] As of 2023, despite evidence of high energy potential, no Indonesian tidal power facilities have been developed.

Use of energy

Transport sector

Much of the energy in Indonesia is used for domestic transportation. The dominance of private vehicles - mostly cars and motorbikes - in Indonesia has led to an enormous demand for fuel. Energy consumption in the transport sector is growing by about 4.5% every year. There is therefore an urgent need for policy reform and infrastructure investment to enhance the energy efficiency of transport, particularly in urban areas.[67]

There are large opportunities to reduce both the energy consumption from the transport sector, for example through the adoption of higher energy efficiency standards for private cars/motorbikes and expanding mass transit networks. Many of these measures would be more cost-effective than the current transport systems.[68] There is also scope to reduce the carbon intensity of transport energy, particularly through replacing diesel with biodiesel or through electrification. Both would require comprehensive supply chain analysis to ensure that the biofuels and power plants are not having wider environmental impacts such as deforestation or air pollution.[69]

Electricity sector

Access to electricity

Over 50% of households in 2011 had an electricity connection. An estimated 63 million people in 2011 did not have direct access to electricity.[70]

However, by 2019, 98.9% of the population had access to electricity.[71]

Organisations

The electricity sector, dominated by the state-owned electricity utility Perusahaan Listrik Negara, is another major consumer of primary energy.

Government policy

Carbon tax

Carbon tax provisions are regulated in Article 13 of the Law 7/2021 in which carbon tax will be imposed on entities producing carbon emissions that have a negative impact on the environment.[72] Based on the Law 7/2021, the imposition of carbon tax will be carried out by focusing on two specific schemes i.e., the carbon tax scheme (cap and tax) and the carbon trade scheme (cap and trade).

In the carbon trade scheme, individual or company ("entities") that produce emissions exceeding the cap are required to purchase for an emission permit certificate ("Sertifikat Izin Emisi"/SIE) other entities that produce emissions below the cap.

In addition, entities can also purchase emission reduction certificates ("Sertifikat Penurunan Emisi"/SPE). However, if the entity is unable to purchase SIE or SPE in full for the resulting emissions, the cap and tax scheme will apply where entities producing residual emissions that exceed the cap will be subject to carbon tax.

Major energy companies in Indonesia

Indonesian firms

- Pertamina, the state-owned oil company

- Pertamina Gas Negara, the state-owned gas company, subsidiary of Pertamina

- Perusahaan Listrik Negara, the state-owned electricity company.

- PT Bumi Resources owned by the Bakrie Group

- PT Medco Energi International, the largest publicly listed oil and gas company in Indonesia

- Adaro Energy, one of the largest coal mining companies in Indonesia

Foreign firms

- US-based firm PT Chevron Pacific Indonesia is the largest producer of crude oil in Indonesia; Chevron produces (2014) around 40% of the crude oil in Indonesia

- Total E&P Indonesia which operates the East Mahakam field in Kalimantan and other fields

- ExxonMobil is one of the main foreign operators in Indonesia

- Equinor, a Norwegian multinational firm, which has been operating in Indonesia since 2007, especially in Eastern Indonesia

- BP which is a major LNG operator in the Tangguh gas field in West Papua.

- ConocoPhillips which currently operates four production-sharing contracts including at Natuna and in Sumatra.

- Inpex, a Japanese firm established in 1966 as North Sumatra Offshore Petroleum Exploration Co. Ltd.

Greenhouse gas emissions

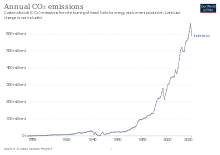

The CO2 emissions of Indonesia in total were over Italy in 2009. However, in all greenhouse gas emissions including construction and deforestation in 2005 Indonesia was top-4 after China, US and Brazil.[73] The carbon intensity of electricity generation is higher than most other countries at over 600 gCO2/kWh.[74]

See also

References

- "Indonesia - Countries & Regions". IEA. Retrieved 30 August 2021.

- "OPEC : Member Countries". www.opec.org. Retrieved 30 August 2021.

- "Indonesia Coal Reserves and Consumption Statistics - Worldometer". www.worldometers.info. Retrieved 30 August 2021.

- "Berapa Potensi Energi Terbarukan di Indonesia? | Databoks". databoks.katadata.co.id (in Indonesian). Retrieved 30 August 2021.

- "Direktorat Jenderal EBTKE - Kementerian ESDM". ebtke.esdm.go.id. Retrieved 30 August 2021.

- "The Role of Natural Gas in ASEAN Energy Security". ASEAN Centre for Energy. 2 December 2015. Retrieved 30 August 2021.

- Nangoy, Fransiska (22 October 2020). Davies, Ed (ed.). "Indonesian govt finalises new rules for renewable electricity". Reuters. Retrieved 2 September 2021.

- Chrysolite, Hanny; Juliane, Reidinar; Chitra, Josefhine; Ge, Mengpin (4 October 2017). "Evaluating Indonesia's Progress on its Climate Commitments".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Rahman, Riska (18 December 2020). "Indonesia kicks off largest solar power plant development". The Jakarta Post. Retrieved 2 September 2021.

- IEA Key World Energy Statistics Statistics 2015 Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, 2014 2012R as in November 2015 Archived 5 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine + 2012 as in March 2014 is comparable to previous years statistical calculation criteria, 2013 Archived 2 September 2014 at the Wayback Machine, 2012 Archived 9 March 2013 at the Wayback Machine, 2011 Archived 27 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine, 2010 Archived 11 October 2010 at the Wayback Machine, 2009 Archived 7 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine, 2006 Archived 12 October 2009 at the Wayback Machine IEA October, crude oil p.11, coal p. 13 gas p. 15

- Simaremare, Arionmaro (2017). "Least Cost High Renewable Energy Penetration Scenarios in the Java Bali Grid System" (PDF). Asia Pacific Solar Research Conference. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 March 2018.

- Arif, Rusli (30 January 2023). "Menteri ESDM Sebut Kapasitas Terpasang Pembangkit Listrik 2023 Ditargetkan Capai 85,1 GW". ruangenergi.con (in Indonesian). Retrieved 24 April 2023.

- "The dirtiest fossil fuel is on the back foot". The Economist. 3 December 2020. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 13 December 2020.

- Cahyafitri, Raras (31 December 2013). "Coal miners to boost production". The Jakarta Post. Retrieved 24 March 2023.

- Cahyafitri, Raras (5 August 2013). "Coal miners sell more in first half, but profits remain stagnant". The Jakarta Post. Retrieved 24 March 2023.

- The True Cost of Coal Archived 30 November 2008 at the Wayback Machine Greenpeace 27 November 2008

- Fadillah, Rangga (21 May 2012). "80 percent of oil and gas revenues pay for subsidies". The Jakarta Post. Archived from the original on 4 June 2012. Retrieved 24 March 2023.

- For some details of Chevron's operations in Indonesia, see the Chevron official Indonesia Fact Sheet Archived 9 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine.

- Azwar, Amahl (27 October 2012). "Chevron kicks off Duri field expansion in Sumatra". The Jakarta Post. Archived from the original on 28 October 2012. Retrieved 24 March 2023.

- "Cepu delay losses to RI could be up to $150m". The Jakarta Post. Archived from the original on 21 May 2009. Retrieved 24 March 2023.

- Azwar, Amahl. "Exxon's new boss urged to be more flexible". The Jakarta Post. Retrieved 24 March 2023.

- Fadillah, Rangga. "Production target 'depends on Cepu block'". The Jakarta Post. Archived from the original on 19 January 2012. Retrieved 24 March 2023.

- Azwar, Amahl (8 January 2013). "RI to focus on gas potential with new projects this year". The Jakarta Post. Archived from the original on 9 January 2013. Retrieved 24 March 2023.

- Azwar, Amahl (26 March 2013). "Total 'keen' to develop Mahakam with Pertamina". The Jakarta Post. Archived from the original on 29 March 2013. Retrieved 24 March 2023.

- Azwar, Amahl (5 October 2013). "Total to 'stop' Mahakam block development amid uncertainty". The Jakarta Post. Retrieved 24 March 2023.

- Aprilian, Salis (22 September 2015). "Sharing risk in the Mahakam Block". The Jakarta Post. Retrieved 24 March 2023.

- Azwar, Amahl (17 May 2013). "Fujian may pay more for Tangguh gas". The Jakarta Post. Retrieved 24 March 2023.

- See the Aceh Production Operations Archived 20 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine of ExxonMobil

- Cahyafitri, Raras (14 September 2015). "ExxonMobil sells Aceh assets to Pertamina". The Jakarta Post. Retrieved 24 March 2023.

- Azwar, Amahl (26 November 2012). "Consortium expects govt approval on East Natuna". The Jakarta Post. Archived from the original on 8 February 2013. Retrieved 24 March 2023.

- Cahyafitri, Raras (14 April 2015). "Pertamina starts delivery of Cepu oil to Cilacap, Balongan". The Jakarta Post. Retrieved 24 March 2023.

- Parlina, Ina; Cahyafitri, Raras (30 December 2015). "Another delay for the Masela gas block development". The Jakarta Post. Retrieved 24 March 2023.

- Hermansyah, Anton (21 March 2016). "Masela saga, another comical brouhaha". The Jakarta Post. Retrieved 24 March 2023.

- Amindoni, Ayomi (23 March 2016). "Masela saga ends as Jokowi announces onshore scheme". The Jakarta Post. Retrieved 24 March 2023.

- Amindoni, Ayomi (24 March 2016). "Inpex, Shell committed to Masela project: SKKMigas". The Jakarta Post. Retrieved 24 March 2023.

- Data are scarce. According to a 2014 study which made reference to Indonesia, "Shale gas resources [in Indonesia] might be substantial, but have been subjected to scant independent scrutiny." See Michael M.D Ross, 'Diversification of Energy Supply: Prospects for Emerging Snergy Sources' Archived 14 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine, ADB Economics Working Paper Series, No 403, 2014, p. 8.

- "Technically Recoverable Shale Oil and Shale Gas Resources: An Assessment of 137 Shale Formations in 41 Countries Outside the United States" (PDF). U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). June 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 December 2011. Retrieved 11 June 2013.

- Campbell, Charlie (25 June 2013). "Indonesia Embraces Shale Fracking — but at What Cost?". Time. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved 24 March 2023.

- Hadiwijoyo, Rohmad (21 April 2014). "CBM could redraft Indonesia's energy charts". The Jakarta Post. Retrieved 24 March 2023.

- Gielen, Dolf; Saygin, Deger; Rigter, Jasper (March 2017). "Renewable Energy Prospects: Indonesia, a REmap analysis". International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA). ISBN 978-92-95111-19-6.

- Campbell, Charlie (25 June 2013). "Indonesia Embraces Shale Fracking — but at What Cost?". Time. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved 24 March 2023.

- Walton, Kate. "Indonesia should put more energy into renewable power". Lowy Institute. Archived from the original on 18 August 2019. Retrieved 3 September 2021.

- Guild, James (6 February 2019). "Indonesia's struggle with renewable energy". East Asia Forum. Retrieved 3 September 2021.

- Vakulchuk, R., Chan, H.Y., Kresnawan, M.R., Merdekawati, M., Overland, I., Sagbakken, H.F., Suryadi, B., Utama, N.A. and Yurnaidi, Z. 2020. Indonesia: how to boost investment in renewable energy. ASEAN Centre for Energy (ACE) Policy Brief Series, No. 6. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/341793782

- Overland, Indra; Sagbakken, Haakon Fossum; Chan, Hoy-Yen; Merdekawati, Monika; Suryadi, Beni; Utama, Nuki Agya; Vakulchuk, Roman (December 2021). "The ASEAN climate and energy paradox". Energy and Climate Change. 2: 100019. doi:10.1016/j.egycc.2020.100019. hdl:11250/2734506.

- Gokkon, Basten (14 February 2020). "In Indonesian renewables bill, activists see chance to move away from coal". Mongabay Environmental News. Retrieved 19 February 2020.

- REN 21 (2013), Renewables Global Status Report, p.125.

- Hidayat, Ali (16 September 2014). "Indonesia Builds First POME Power Generator". Tempo. Retrieved 24 March 2023.

- "Indonesia: hydropower energy capacity 2020". Statista. Retrieved 30 August 2021.

- Hasan, M. H.; Mahlia, T. M. I.; Nur, Hadi (1 May 2012). "A review on energy scenario and sustainable energy in Indonesia". Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 16 (4): 2316–2328. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2011.12.007. ISSN 1364-0321.

- REN 21 (2013), Renewables Global Status Report, p.109.

- Tang, Shengwen; Chen, Jingtao; Sun, Peigui; Li, Yang; Yu, Peng; Chen, E. (1 June 2019). "Current and future hydropower development in Southeast Asia countries (Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand and Myanmar)". Energy Policy. 129: 239–249. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2019.02.036. ISSN 0301-4215. S2CID 159049194.

- Renewables 2007 Global Status Report Archived 29 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine, REN21 sihteeristö (Pariisi) ja Worldwatch institute (Washington, DC), 2008, page 8

- Renewables 2013 Global Status Report

- Nugroho, Hanan (23 October 2013). "Geothermal: Challenges to keep the development on track". The Jakarta Post. Retrieved 24 March 2023.

- "Govt set to raise prices of geothermal power". The Jakarta Post. Retrieved 24 March 2023.

- Susanto, Slamet (13 June 2013). "RI's geothermal energy still 'untouched'". The Jakarta Post. Retrieved 24 March 2023.

- "Tapping into Indonesia's Geothermal Resources". Climate Investment Funds. 6 July 2020. Retrieved 28 July 2020.

- Hasan, Muhammad Heikal; Mahlia, Teuku Meurah Indra; Nur, Hadi (2012). "A review on energy scenario and sustainable energy in Indonesia". Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 16 (4): 2316–2328. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2011.12.007.

- Hirsch, B., K. Burman, C. Davidson, M. Elchinger, R. Hardison, D. Karsiwulan, and B. Castermans. 2015. Sustainable Energy in Remote Indonesian Grids: Accelerating Project Development. (Technical Report) NREL/TP-7A40-64018. Golden, CO: National Renewable Energy Laboratory. http://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy15osti/64018.pdf. Archived 30 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- Susanto, Slamet (5 November 2012). "Pandanmino, self-sufficient in electricity due to wind power". The Jakarta Post. Archived from the original on 8 November 2012. Retrieved 24 March 2023.

- Tampubolon, Agus Praditya (17 July 2019). Simamora, Pamela (ed.). "Wind Farm is Coming to Indonesia, and The Power Sector isn't Ready". IESR. Archived from the original on 30 August 2021. Retrieved 30 August 2021.

- Andi, Hajramurni (2 July 2018). "Jokowi inaugurates first Indonesian wind farm in Sulawesi". The Jakarta Post. Retrieved 19 February 2020.

- "Indonesia Solar Potential Report". IESR. Retrieved 30 August 2021.

- For a survey of issues involved in expanding capacity in the solar electricity sector in developing Asia, see Michael M.D Ross, 'Diversification of Energy Supply: Prospects for Emerging Energy Sources', Archived 14 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine ADB Economics Working Paper Series, No 403, 2014.

- Blunden, L. S.; Bahaj, A. S.; Aziz, N. S. (1 January 2013). "Tidal current power for Indonesia? An initial resource estimation for the Alas Strait". Renewable Energy. Selected papers from World Renewable Energy Congress - XI. 49: 137–142. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2012.01.046. ISSN 0960-1481.

- Leung KH (2016). "Indonesia's Summary Transport Assessment" (PDF). Asian Development Bank. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 April 2018.

- Colenbrander S, Gouldson A, Sudmant AH, Papargyropoulou E (2015). "The economic case for low-carbon development in rapidly growing developing world cities: A case study of Palembang, Indonesia" (PDF). Energy Policy. 80: 24–35. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2015.01.020. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 August 2017.

- Kharina, Anastasia; Malins, Chris; Searle, Stephanie (8 August 2016). "Biofuels policy in Indonesia: Overview and status report". International Council on Clean Transportation. Retrieved 24 March 2023.

- REN 21 (2013), Renewables Global Status Report, p.123, Table R17.

- "Indonesia: Electrification rate 2020".

- "Carbon Tax Provisions - ADCO Law". Archived from the original on 10 November 2021. Retrieved 10 November 2021.

- World carbon dioxide emissions data by country: China speeds ahead of the rest Guardian 31 January 2011

- Electric Insights Quarterly (PDF) (Report). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 December 2020.