Shale gas

Shale gas is an unconventional natural gas that is found trapped within shale formations.[1] Since the 1990s a combination of horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing has made large volumes of shale gas more economical to produce, and some analysts expect that shale gas will greatly expand worldwide energy supply.[2]

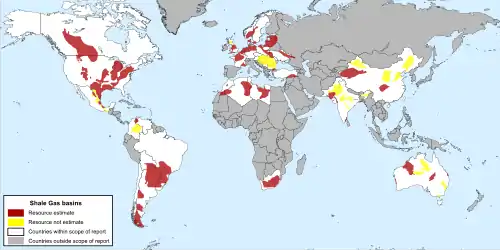

Shale gas has become an increasingly important source of natural gas in the United States since the start of this century, and interest has spread to potential gas shales in the rest of the world.[3] China is estimated to have the world's largest shale gas reserves.[4]

A 2013 review by the United Kingdom Department of Energy and Climate Change noted that most studies of the subject have estimated that life-cycle greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from shale gas are similar to those of conventional natural gas, and are much less than those from coal, usually about half the greenhouse gas emissions of coal; the noted exception was a 2011 study by Howarth and others of Cornell University, which concluded that shale GHG emissions were as high as those of coal.[5][6] More recent studies have also concluded that life-cycle shale gas GHG emissions are much less than those of coal,[7][8][9][10] among them, studies by Natural Resources Canada (2012),[11] and a consortium formed by the US National Renewable Energy Laboratory with a number of universities (2012).[12]

Some 2011 studies pointed to high rates of decline of some shale gas wells as an indication that shale gas production may ultimately be much lower than is currently projected.[13][14] But shale-gas discoveries are also opening up substantial new resources of tight oil, also known as "shale oil".[15]

History

United States

Shale gas was first extracted as a resource in Fredonia, New York, in 1821,[16][17] in shallow, low-pressure fractures. Horizontal drilling began in the 1930s, and in 1947 a well was first fracked in the U.S.[3]

Federal price controls on natural gas led to shortages in the 1970s.[18] Faced with declining natural gas production, the federal government invested in many supply alternatives, including the Eastern Gas Shales Project, which lasted from 1976 to 1992, and the annual FERC-approved research budget of the Gas Research Institute, where the federal government began extensive research funding in 1982, disseminating the results to industry.[3] The federal government also provided tax credits and rules benefiting the industry in the 1980 Energy Act.[3] The Department of Energy later partnered with private gas companies to complete the first successful air-drilled multi-fracture horizontal well in shale in 1986. The federal government further incentivized drilling in shale via the Section 29 tax credit for unconventional gas from 1980–2000. Microseismic imaging, a crucial input to both hydraulic fracturing in shale and offshore oil drilling, originated from coalbeds research at Sandia National Laboratories. The DOE program also applied two technologies that had been developed previously by industry, massive hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling, to shale gas formations,[19] which led to microseismic imaging.

Although the Eastern Gas Shales Project had increased gas production in the Appalachian and Michigan basins, shale gas was still widely seen as marginal to uneconomic without tax credits, and shale gas provided only 1.6% of US gas production in 2000, when the federal tax credits expired.[18]

George P. Mitchell is regarded as the father of the shale gas industry, since he made it commercially viable in the Barnett Shale by getting costs down to $4 per 1 million British thermal units (1,100 megajoules).[20] Mitchell Energy achieved the first economical shale fracture in 1998 using slick-water fracturing.[21][22][23] Since then, natural gas from shale has been the fastest growing contributor to total primary energy in the United States, and has led many other countries to pursue shale deposits. According to the IEA, shale gas could increase technically recoverable natural gas resources by almost 50%.[24]

In 2000 shale gas provided only 1% of U.S. natural gas production; by 2010 it was over 20% and the U.S. Energy Information Administration predicted that by 2035, 46% of the United States' natural gas supply will come from shale gas.[3]

The Obama administration believed that increased shale gas development would help reduce greenhouse gas emissions.[25]

Geology

_Conventional_Deposits.svg.png.webp)

Because shales ordinarily have insufficient permeability to allow significant fluid flow to a wellbore, most shales are not commercial sources of natural gas.[26] Shale gas is one of a number of unconventional sources of natural gas; others include coalbed methane, tight sandstones, and methane hydrates. Shale gas areas are often known as resource plays[27] (as opposed to exploration plays). The geological risk of not finding gas is low in resource plays, but the potential profits per successful well are usually also lower.

Shale has low matrix permeability,[26] and so gas production in commercial quantities requires fractures to provide permeability. Shale gas has been produced for years from shales with natural fractures; the shale gas boom in recent years has been due to modern technology in hydraulic fracturing (fracking) to create extensive artificial fractures around well bores.

Horizontal drilling is often used with shale gas wells, with lateral lengths up to 10,000 feet (3,000 m) within the shale, to create maximum borehole surface area in contact with the shale.

Shales that host economic quantities of gas have a number of common properties. They are rich in organic material (0.5% to 25%),[28] and are usually mature petroleum source rocks in the thermogenic gas window, where high heat and pressure have converted petroleum to natural gas. They are sufficiently brittle and rigid enough to maintain open fractures.[26]

Some of the gas produced is held in natural fractures, some in pore spaces,[26] and some is adsorbed onto the shale matrix. Further, the adsorption of gas is a process of physisorption, exothermic and spontaneous.[29] The gas in the fractures is produced immediately; the gas adsorbed onto organic material is released as the formation pressure is drawn down by the well.

Shale gas by country

Although the shale gas potential of many nations is being studied, as of 2013, only the US, Canada, and China produce shale gas in commercial quantities, and only the US and Canada have significant shale gas production.[30] While China has ambitious plans to dramatically increase its shale gas production, these efforts have been checked by inadequate access to technology, water, and land.[31][32]

The table below is based on data collected by the Energy Information Administration agency of the United States Department of Energy.[33] Numbers for the estimated amount of "technically recoverable"[34] shale gas resources are provided alongside numbers for proven natural gas reserves.

| Country | Estimated technically recoverable shale gas (trillion cubic feet) | Proven natural gas resource estimates of all types (trillion cubic feet) | Date of report[33] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1,115 | 124 | 2013 | |

| 2 | 802 | 12 | 2013 | |

| 3 | 707 | 159 | 2013 | |

| 4 | 665 | 318 | 2013 | |

| 5 | 573 | 68 | 2013 | |

| 6 | 545 | 17 | 2013 | |

| 7 | 485 | — | 2013 | |

| 8 | 437 | 43 | 2013 | |

| 9 | 285 | 1,688 | 2013 | |

| 10 | 245 | 14 | 2013 | |

| 11 | 580 | 150 | 2013 |

The US EIA had made an earlier estimate of total recoverable shale gas in various countries in 2011, which for some countries differed significantly from the 2013 estimates.[35] The total recoverable shale gas in the United States, which was estimated at 862 trillion cubic feet in 2011, was revised downward to 665 trillion cubic feet in 2013. Recoverable shale gas in Canada, which was estimated to be 388 TCF in 2011, was revised upward to 573 TCF in 2013.

For the United States, EIA estimated (2013) a total "wet natural gas" resource of 2,431 tcf, including both shale and conventional gas. Shale gas was estimated to be 27% of the total resource.[33] "Wet natural gas" is methane plus natural gas liquids, and is more valuable than dry gas.[36][37]

For the rest of the world (excluding US), EIA estimated (2013) a total wet natural gas resource of 20,451 trillion cubic feet (579.1×1012 m3). Shale gas was estimated to be 32% of the total resource.[33]

Europe has a shale gas resource estimate of 639 trillion cubic feet (18.1×1012 m3) compared with America's reserves 862 trillion cubic feet (24.4×1012 m3), but its geology is more complicated and the oil and gas more expensive to extract, with a well likely to cost as much as three-and-a-half times more than one in the United States.[38] Europe would be the fastest growing region, accounting for the highest CAGR of 59.5%, in terms of volume owing to availability of shale gas resource estimates in more than 14 European countries.[39]

Environment

The extraction and use of shale gas can affect the environment through the leaking of extraction chemicals and waste into water supplies, the leaking of greenhouse gases during extraction, and the pollution caused by the improper processing of natural gas . A challenge to preventing pollution is that shale gas extractions varies widely in this regard, even between different wells in the same project; the processes that reduce pollution sufficiently in one extraction may not be enough in another.[3]

In 2013 the European Parliament agreed that environmental impact assessments will not be mandatory for shale gas exploration activities and shale gas extraction activities will be subject to the same terms as other gas extraction projects.[40]

Climate

Barack Obama's administration had sometimes promoted shale gas, in part because of its belief that it releases fewer greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions than other fossil fuels. In a 2010 letter to President Obama, Martin Apple of the Council of Scientific Society Presidents cautioned against a national policy of developing shale gas without a more certain scientific basis for the policy. This umbrella organization that represents 1.4 million scientists noted that shale gas development "may have greater GHG emissions and environmental costs than previously appreciated."[41]

In late 2010, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency[42] issued a report which concluded that shale gas emits larger amounts of methane, a potent greenhouse gas, than does conventional gas, but still far less than coal. Methane is a powerful greenhouse gas, although it stays in the atmosphere for only one tenth as long a period as carbon dioxide. Recent evidence suggests that methane has a global warming potential (GWP) that is 105-fold greater than carbon dioxide when viewed over a 20-year period and 33-fold greater when viewed over a 100-year period, compared mass-to-mass.[43]

Several studies which have estimated lifecycle methane leakage from shale gas development and production have found a wide range of leakage rates, from less than 1% of total production to nearly 8%.[44]

A 2011 study published in Climatic Change Letters claimed that the production of electricity using shale gas may lead to as much or more life-cycle GWP than electricity generated with oil or coal.[45] In the peer-reviewed paper, Cornell University professor Robert W. Howarth, a marine ecologist, and colleagues claimed that once methane leak and venting impacts are included, the life-cycle greenhouse gas footprint of shale gas is far worse than those of coal and fuel oil when viewed for the integrated 20-year period after emission. On the 100-year integrated time frame, this analysis claims shale gas is comparable to coal and worse than fuel oil. However, other studies have pointed out flaws with the paper and come to different conclusions. Among those are assessments by experts at the U.S. Department of Energy,[46] peer-reviewed studies by Carnegie Mellon University[47] and the University of Maryland,[48] and the Natural Resources Defense Council, which claimed that the Howarth et al. paper's use of a 20-year time horizon for global warming potential of methane is "too short a period to be appropriate for policy analysis."[49] In January 2012, Howarth's colleagues at Cornell University, Lawrence Cathles et al., responded with their own peer-reviewed assessment, noting that the Howarth paper was "seriously flawed" because it "significantly overestimate[s] the fugitive emissions associated with unconventional gas extraction, undervalue[s] the contribution of 'green technologies' to reducing those emissions to a level approaching that of conventional gas, base[s] their comparison between gas and coal on heat rather than electricity generation (almost the sole use of coal), and assume[s] a time interval over which to compute the relative climate impact of gas compared to coal that does not capture the contrast between the long residence time of CO2 and the short residence time of methane in the atmosphere." The author of that response, Lawrence Cathles, wrote that "shale gas has a GHG footprint that is half and perhaps a third that of coal," based upon "more reasonable leakage rates and bases of comparison."[50]

In April 2013 the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency lowered its estimate of how much methane leaks from wells, pipelines and other facilities during production and delivery of natural gas by 20 percent. The EPA report on greenhouse emissions credited tighter pollution controls instituted by the industry for cutting an average of 41.6 million metric tons of methane emissions annually from 1990 through 2010, a reduction of more than 850 million metric tons overall. The Associated Press noted that "The EPA revisions came even though natural gas production has grown by nearly 40 percent since 1990."[51]

Using data from the Environmental Protection Agency's 2013 Greenhouse Gas Inventory[52] yields a methane leakage rate of about 1.4%, down from 2.3% from the EPA's previous Inventory.[53]

Life cycle comparison for more than global warming potential

A 2014 study from Manchester University presented the "First full life cycle assessment of shale gas used for electricity generation." By full life cycle assessment, the authors explained that they mean the evaluation of nine environmental factors beyond the commonly performed evaluation of global warming potential. The authors concluded that, in line with most of the published studies for other regions, that shale gas in the United Kingdom would have a global warming potential "broadly similar" to that of conventional North Sea gas, although shale gas has the potential to be higher if fugitive methane emissions are not controlled, or if per-well ultimate recoveries in the UK are small. For the other parameters, the highlighted conclusions were that, for shale gas in the United Kingdom in comparison with coal, conventional and liquefied gas, nuclear, wind and solar (PV).

- Shale gas worse than coal for three impacts and better than renewables for four.

- It has higher photochemical smog and terrestrial toxicity than the other options.

- Shale gas a sound environmental option only if accompanied by stringent regulation.[54][55][56]

Dr James Verdon has published a critique of the data produced, and the variables that may affect the results.[57]

Water and air quality

Chemicals are added to the water to facilitate the underground fracturing process that releases natural gas. Fracturing fluid is primarily water and approximately 0.5% chemical additives (friction reducer, agents countering rust, agents killing microorganism). Since (depending on the size of the area) millions of liters of water are used, this means that hundreds of thousands of liters of chemicals are often injected into the subsurface.[58] About 50% to 70% of the injected volume of contaminated water is recovered and stored in above-ground ponds to await removal by tanker. The remaining volume remains in the subsurface. Hydraulic fracturing opponents fear that it can lead to contamination of groundwater aquifers, though the industry deems this "highly unlikely". However, foul-smelling odors and heavy metals contaminating the local water supply above-ground have been reported.[59]

Besides using water and industrial chemicals, it is also possible to frack shale gas with only liquified propane gas. This reduces the environmental degradation considerably. The method was invented by GasFrac, of Alberta, Canada.[60]

Hydraulic fracturing was exempted from the Safe Drinking Water Act in the Energy Policy Act of 2005.[61]

A study published in May 2011 concluded that shale gas wells have seriously contaminated shallow groundwater supplies in northeastern Pennsylvania with flammable methane. However, the study does not discuss how pervasive such contamination might be in other areas drilled for shale gas.[62]

The United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) announced 23 June 2011 that it will examine claims of water pollution related to hydraulic fracturing in Texas, North Dakota, Pennsylvania, Colorado and Louisiana.[63] On 8 December 2011, the EPA issued a draft finding which stated that groundwater contamination in Pavillion, Wyoming may be the result of fracking in the area. The EPA stated that the finding was specific to the Pavillion area, where the fracking techniques differ from those used in other parts of the U.S. Doug Hock, a spokesman for the company which owns the Pavillion gas field, said that it is unclear whether the contamination came from the fracking process.[64] Wyoming's Governor Matt Mead called the EPA draft report "scientifically questionable" and stressed the need for additional testing.[65] The Casper Star-Tribune also reported on 27 December 2011, that the EPA's sampling and testing procedures "didn’t follow their own protocol" according to Mike Purcell, the director of the Wyoming Water Development Commission.[66]

A 2011 study by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology concluded that "The environmental impacts of shale development are challenging but manageable." The study addressed groundwater contamination, noting "There has been concern that these fractures can also penetrate shallow freshwater zones and contaminate them with fracturing fluid, but there is no evidence that this is occurring". This study blames known instances of methane contamination on a small number of sub-standard operations, and encourages the use of industry best practices to prevent such events from recurring.[67]

In a report dated 25 July 2012, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency announced that it had completed its testing of private drinking water wells in Dimock, Pennsylvania. Data previously supplied to the agency by residents, the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection, and Cabot Oil and Gas Exploration had indicated levels of arsenic, barium or manganese in well water at five homes at levels that could present a health concern. In response, water treatment systems that can reduce concentrations of those hazardous substances to acceptable levels at the tap were installed at affected homes. Based on the outcome of sampling after the treatment systems were installed, the EPA concluded that additional action by the Agency was not required.[68]

A Duke University study of Blacklick Creek (Pennsylvania), carried out over two years, took samples from the creek upstream and down stream of the discharge point of Josephine Brine Treatment Facility. Radium levels in the sediment at the discharge point are around 200 times the amount upstream of the facility. The radium levels are "above regulated levels" and present the "danger of slow bio-accumulation" eventually in fish. The Duke study "is the first to use isotope hydrology to connect the dots between shale gas waste, treatment sites and discharge into drinking water supplies." The study recommended "independent monitoring and regulation" in the United States due to perceived deficiencies in self-regulation.[69][70]

What is happening is the direct result of a lack of any regulation. If the Clean Water Act was applied in 2005 when the shale gas boom started this would have been prevented. In the UK, if shale gas is going to develop, it should not follow the American example and should impose environmental regulation to prevent this kind of radioactive buildup.

— Avner Vengosh[69]

According to the US Environmental Protection Agency, the Clean Water Act applies to surface stream discharges from shale gas wells:

- "6) Does the Clean Water Act apply to discharges from Marcellus Shale Drilling operations?

- Yes. Natural gas drilling can result in discharges to surface waters. The discharge of this water is subject to requirements under the Clean Water Act (CWA)."[71]

Earthquakes

Hydraulic fracturing routinely produces microseismic events much too small to be detected except by sensitive instruments. These microseismic events are often used to map the horizontal and vertical extent of the fracturing.[72] However, as of late 2012, there have been three known instances worldwide of hydraulic fracturing, through induced seismicity, triggering quakes large enough to be felt by people.[73]

On 26 April 2012, the Asahi Shimbun reported that United States Geological Survey scientists have been investigating the recent increase in the number of magnitude 3 and greater earthquake in the midcontinent of the United States. Beginning in 2001, the average number of earthquakes occurring per year of magnitude 3 or greater increased significantly, culminating in a six-fold increase in 2011 over 20th century levels. A researcher in Center for Earthquake Research and Information of University of Memphis assumes water pushed back into the fault tends to cause earthquake by slippage of fault.[74][75]

Over 109 small earthquakes (Mw 0.4–3.9) were detected during January 2011 to February 2012 in the Youngstown, Ohio area, where there were no known earthquakes in the past. These shocks were close to a deep fluid injection well. The 14 month seismicity included six felt earthquakes and culminated with a Mw 3.9 shock on 31 December 2011. Among the 109 shocks, 12 events greater than Mw 1.8 were detected by regional network and accurately relocated, whereas 97 small earthquakes (0.4<Mw<1.8) were detected by the waveform correlation detector. Accurately located earthquakes were along a subsurface fault trending ENE-WSW—consistent with the focal mechanism of the main shock and occurred at depths 3.5–4.0 km in the Precambrian basement.

On 19 June 2012, the United States Senate Committee on Energy & Natural Resources held a hearing entitled, "Induced Seismicity Potential in Energy Technologies." Dr. Murray Hitzman, the Charles F. Fogarty Professor of Economic Geology in the Department of Geology and Geological Engineering at the Colorado School of Mines in Golden, CO testified that "About 35,000 hydraulically fractured shale gas wells exist in the United States. Only one case of felt seismicity in the United States has been described in which hydraulic fracturing for shale gas development is suspected, but not confirmed. Globally only one case of felt induced seismicity at Blackpool, England has been confirmed as being caused by hydraulic fracturing for shale gas development."[76]

Human health impacts

A comprehensive review of the public health effects of energy fuel cycles in Europe finds that coal causes 6 to 98 deaths per TWh (average 25 deaths per TWh), compared to natural gas’ 1 to 11 deaths per TWh (average 3 deaths per TWh). These numbers include both accidental deaths and pollution-related deaths.[77] Coal mining is one of the most dangerous professions in the United States, resulting in between 20 and 40 deaths annually, compared to between 10 and 20 for oil and gas extraction.[78] Worker accident risk is also far higher with coal than gas. In the United States, the oil and gas extraction industry is associated with one to two injuries per 100 workers each year. Coal mining, on the other hand, contributes to four injuries per 100 workers each year. Coal mines collapse, and can take down roads, water and gas lines, buildings and many lives with them.[79]

Average damages from coal pollutants are two orders of magnitude larger than damages from natural gas. SO2, NOx, and particulate matter from coal plants create annual damages of $156 million per plant compared to $1.5 million per gas plant.[80] Coal-fired power plants in the United States emit 17–40 times more SOx emissions per MWh than natural gas, and 1–17 times as much NOx per MWh.[81] Lifecycle CO2 emissions from coal plants are 1.8-2.3 times greater (per KWh) than natural gas emissions.[82]

The air quality advantages of natural gas over coal have been borne out in Pennsylvania, according to studies by the RAND Corporation and the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection. The shale boom in Pennsylvania has led to dramatically lower emissions of sulfur dioxide, fine particulates, and volatile organic compounds (VOCs).[9]

Physicist Richard A. Muller has said that the public health benefits from shale gas, by displacing harmful air pollution from coal, far outweigh its environmental costs. In a 2013 report for the Centre for Policy Studies, Muller wrote that air pollution, mostly from coal burning, kills over three million people each year, primarily in the developing world. The report states that "Environmentalists who oppose the development of shale gas and fracking are making a tragic mistake."[10] In China, shale gas development is seen as a way to shift away from coal and decrease serious air pollution problems created by burning coal.[83]

Social impacts

Shale gas development leads to a series of tiered socio-economic effects during boom conditions.[84] These include both positive and negative aspects. Along with other forms of unconventional energy, shale oil and gas extraction has three direct initial aspects: increased labour demand (employment);[85] income generation (higher wages);[86] and disturbance to land and/or other economic activity, potentially resulting in compensation. Following these primary direct effects, the following secondary effects occur: in-migration (to meet labour demand), attracting temporary and/or permanent residents, Increased demand for goods and services; leading to increased indirect employment.[87] The latter two of these can fuel each other in a circular relationship during boom conditions (i.e. increased demand for goods and services creates employment which increase demand for goods and services). These increases place strain on existing infrastructure. These conditions lead to tertiary socio-economic effects in the form of increased housing values; increased rental costs; construction of new dwellings (which may take time to be completed); demographic and cultural changes as new types of people move to the host region;[88] changes to income distribution; potential for conflict; potential for increased substance abuse; and provision of new types of services.[84] The reverse of these effects occurs over bust conditions, with a decline in primary effects leading to a decline in secondary effects and so on. However, the bust period of unconventional extraction may not be as severe as from conventional energy extraction.[89] Due to the dispersed nature of the industry and ability to adjust drilling rates, there is debate in the literature as to how intense the bust phase is and how host communities can maintain social resilience during downturns.[90]

Landscape impacts

Coal mining radically alters whole mountain and forest landscapes. Beyond the coal removed from the earth, large areas of forest are turned inside out and blackened with toxic and radioactive chemicals. There have been reclamation successes, but hundreds of thousands of acres of abandoned surface mines in the United States have not been reclaimed, and reclamation of certain terrain (including steep terrain) is nearly impossible.[91]

Where coal exploration requires altering landscapes far beyond the area where the coal is, aboveground natural gas equipment takes up just one percent of the total surface land area from where gas will be extracted.[92] The environmental impact of gas drilling has changed radically in recent years. Vertical wells into conventional formations used to take up one-fifth of the surface area above the resource, a twenty-fold higher impact than current horizontal drilling requires. A six-acre horizontal drill pad can thus extract gas from an underground area 1,000 acres in size.

The impact of natural gas on landscapes is even less and shorter in duration than the impact of wind turbines. The footprint of a shale gas derrick (3–5 acres) is only a little larger than the land area necessary for a single wind turbine.[93] But it requires less concrete, stands one-third as tall, and is present for just 30 days instead of 20–30 years. Between 7 and 15 weeks are spent setting up the drill pad and completing the actual hydraulic fracture. At that point, the drill pad is removed, leaving behind a single garage-sized wellhead that remains for the lifetime of the well. A study published in 2015 on the Fayetteville Shale found that a mature gas field impacted about 2% of the land area and substantially increased edge habitat creation. Average land impact per well was 3 hectares (about 7 acres) [94]

Water

With coal mining, waste materials are piled at the surface of the mine, creating aboveground runoff that pollutes and alters the flow of regional streams. As rain percolates through waste piles, soluble components are dissolved in the runoff and cause elevated total dissolved solids (TDS) levels in local water bodies.[91] Sulfates, calcium, carbonates and bicarbonates – the typical runoff products of coalmine waste materials – make water unusable for industry or agriculture and undrinkable for humans.[95] Acid mine wastewater can drain into groundwater, causing significant contamination. Explosive blasting in a mine can cause groundwater to seep to lower-than-normal depths or connect two aquifers that were previously distinct, exposing both to contamination by mercury, lead, and other toxic heavy metals.

Contamination of surface waterways and groundwater with fracking fluids is problematic.[96] Shale gas deposits are generally several thousand feet below ground. There have been instances of methane migration, improper treatment of recovered wastewater, and pollution via reinjection wells.[97]

In most cases, the life-cycle water intensity and pollution associated with coal production and combustion far outweigh those related to shale gas production. Coal resource production requires at least twice as much water per million British thermal units compared to shale gas production.[98] And while regions like Pennsylvania have experienced an absolute increase in water demand for energy production thanks to the shale boom, shale wells actually produce less than half the wastewater per unit of energy compared to conventional natural gas.[92]

Coal-fired power plants consume two to five times as much water as natural gas plants. Where 520–1040 gallons of water are required per MWh of coal, gas-fired combined cycle power requires 130–500 gallons per MWh.[99] The environmental impact of water consumption at the point of power generation depends on the type of power plant: plants either use evaporative cooling towers to release excess heat or discharge water to nearby rivers.[100] Natural gas combined-cycle power (NGCC), which captures the exhaust heat generated by combusting natural gas to power a steam generator, are considered the most efficient large-scale thermal power plants. One study found that the life-cycle demand for water from coal power in Texas could be more than halved by switching the fleet to NGCC.[101]

All told, shale gas development in the United States represents less than half a percent of total domestic freshwater consumption, although this portion can reach as high as 25 percent in particularly arid regions.[102]

Hazards

Drilling depths of 1,000 to 3,000 m, then injection of a fluid composed of water, sand and detergents under pressure (600 bar), are required to fracture the rock and release the gas. These operations have already caused groundwater contaminations across the Atlantic, mainly as a result of hydrocarbon leakage along the casings. In addition, between 2% and 8% of the extracted fuel would be released to the atmosphere at wells (still in the United States). However, it is mainly composed of methane (CH4), a greenhouse gas that is considerably more powerful than CO2.

Surface installations must be based on concrete or paved soils connected to the road network. A gas pipeline is also required to evacuate production. In total, each farm would occupy an average area of 3.6 ha. However, the gas fields are relatively small. Exploitation of shale gas could therefore lead to fragmentation of landscapes. Finally, a borehole requires about 20 million liters of water, the daily consumption of about 100,000 inhabitants.[103]

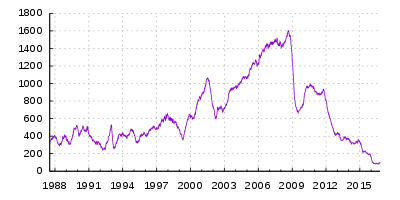

Economics

Although shale gas has been produced for more than 100 years in the Appalachian Basin and the Illinois Basin of the United States, the wells were often marginally economic. Advances in hydraulic fracturing and horizontal completions have made shale-gas wells more profitable.[104] Improvements in moving drilling rigs between nearby locations, and the use of single well pads for multiple wells have increased the productivity of drilling shale gas wells.[105] As of June 2011, the validity of the claims of economic viability of these wells has begun to be publicly questioned.[106] Shale gas tends to cost more to produce than gas from conventional wells, because of the expense of the massive hydraulic fracturing treatments required to produce shale gas, and of horizontal drilling.[107]

The cost of extracting offshore shale gas in the UK were estimated to be more than $200 per barrel of oil equivalent (UK North Sea oil prices were about $120 per barrel in April 2012). However, no cost figures were made public for onshore shale gas.[108]

North America has been the leader in developing and producing shale gas. The economic success of the Barnett Shale play in Texas in particular has spurred the search for other sources of shale gas across the United States and Canada,

Some Texas residents think fracking is using too much of their groundwater, but drought and other growing uses are also part of the causes of the water shortage there.[109]

A Visiongain research report calculated the 2011 worth of the global shale-gas market as $26.66 billion.[110]

A 2011 New York Times investigation of industrial emails and internal documents found that the financial benefits of unconventional shale gas extraction may be less than previously thought, due to companies intentionally overstating the productivity of their wells and the size of their reserves.[111] The article was criticized by, among others, the New York Times' own Public Editor for lack of balance in omitting facts and viewpoints favorable to shale gas production and economics.[112]

In first quarter 2012, the United States imported 840 billion cubic feet (Bcf) (785 from Canada) while exporting 400 Bcf (mostly to Canada); both mainly by pipeline.[113] Almost none is exported by ship as LNG, as that would require expensive facilities. In 2012, prices went down to US$3 per million British thermal units ($10/MWh) due to shale gas.[114]

A recent academic paper on the economic impacts of shale gas development in the US finds that natural gas prices have dropped dramatically in places with shale deposits with active exploration. Natural gas for industrial use has become cheaper by around 30% compared to the rest of the US.[115] This stimulates local energy intensive manufacturing growth, but brings the lack of adequate pipeline capacity in the US in sharp relief.[116]

One of the byproducts of shale gas exploration is the opening up of deep underground shale deposits to "tight oil" or shale oil production. By 2035, shale oil production could "boost the world economy by up to $2.7 trillion, a PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) report says. It has the potential to reach up to 12 percent of the world’s total oil production — touching 14 million barrels a day — "revolutionizing" the global energy markets over the next few decades." [15]

According to a 2013 Forbes magazine article, generating electricity by burning natural gas is cheaper than burning coal if the price of gas remains below US$3 per million British thermal units ($10/MWh) or about $3 per 1000 cubic feet.[20] Also in 2013, Ken Medlock, Senior Director of the Baker Institute's Center for Energy Studies, researched US shale gas break-even prices. "Some wells are profitable at $2.65 per thousand cubic feet, others need $8.10…the median is $4.85," Medlock said.[117] Energy consultant Euan Mearns estimates that, for the US, "minimum costs [are] in the range $4 to $6 / mcf. [per 1000 cubic feet or million BTU]."[118][119]

See also

References

- "U.S. Energy Information Administration". Eia.gov. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- Krauss, Clifford (9 October 2009). "New way to tap gas may expand global supplies". The New York Times. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- Stevens, Paul (August 2012). "The 'Shale Gas Revolution': Developments and Changes". Chatham House. Retrieved 15 August 2012.

- Staff (5 April 2011) World Shale Gas Resources: An Initial Assessment of 14 Regions Outside the United States US Energy Information Administration, Analysis and Projections, Retrieved 26 August 2012

- David J. C. MacKay and Timothy J. Stone, Potential Greenhouse Gas Emissions Associated with Shale Gas Extraction and Use, 9 September 2013. MacKay and Stone wrote (p.3): "The Howarth estimate may be unrealistically high, as discussed in Appendix A, and should be treated with caution."

- Howarth, Robert; Sontaro, Renee; Ingraffea, Anthony (12 November 2010). "Methane and the greenhouse-gas footprint of natural gas from shale formations" (PDF). Springerlink.com. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- Burnham and others, "Life-cycle greenhouse gas emissions of shale gas, natural gas, coal, and petroleum", Environmental Science and Technology, 17 January 2012, v.46 n.2 p.619-627.

- Keating, Martha; Baum, Ellen; Hennen, Amy (June 2001). "Cradle to Grave: The Environmental Impacts from Coal" (PDF). Clean Air Task Force. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 October 2013. Retrieved 2 October 2013.

- James Conca, Fugitive Fracking Gets Bum Rap, Forbes, 18 February 2013.

- Why Every Serious Environmentalist Should Favour Fracking Archived 12 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine, 2013 report by Richard A. Muller and Elizabeth A. Muller of Berkeley Earth

- Natural Resources Canada, Shale gas Archived 21 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine, 14 December 2012.

- Jeffrey Logan, Garvin Heath, and Jordan Macknick, Elizabeth Paranhos, William Boyd, and Ken Carlson, Natural Gas and the Transformation of the U.S. Energy Sector: Electricity, Technical Report NREL/TP-6A50-55538, Nov. 2012.

- David Hughes (May 2011). "Will Natural Gas Fuel America in the 21st Century?" Post Carbon Institute,

- Arthur Berman (8 February 2011). "After the gold rush: A perspective on future U.S. natural gas supply and price". Theoildrum.com. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- Syed Rashid Husain. "Shale Gas Revolution Changes Geopolitics." Saudi Gazette. 24 February 2013. Archived 18 April 2013 at archive.today

- KEN MILAM, EXPLORER Correspondent. "Name the gas industry birthplace: Fredonia, N.Y.?". Aapg.org. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- "New York's natural gas history – a long story, but not the final chapter" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 November 2019. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

- Zhongmin Wang and Alan Krupnick, A Retrospective Review of Shale Gas Development in the United States Archived 19 March 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Resources for the Futures, Apr. 2013.

- KEN MILAM, EXPLORER Correspondent. "Proceedings from the 2nd Annual Methane Recovery from Coalbeds Symposium". Aapg.org. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- "Will Natural Gas Stay Cheap Enough To Replace Coal And Lower US Carbon Emissions". Forbes. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- Miller, Rich; Loder, Asjylyn; Polson, Jim (6 February 2012). "Americans Gaining Energy Independence". Bloomberg. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- "The Breakthrough Institute. Interview with Dan Steward, former Mitchell Energy Vice President. December 2011". Thebreakthrough.org. Archived from the original on 7 March 2012. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- "America's bounty: Gas works". The Economist. 14 July 2012. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- "International Energy Agency (IEA). "World Energy Outlook Special Report on Unconventional Gas: Golden Rules for a Golden Age of Gas?"" (PDF). Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- "Statement on U.S.-China shale gas resource initiative". America.gov. 17 November 2009. Archived from the original on 28 November 2009. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- Richardson, Ethan J.; Montenari, Michael (2020). "Assessing shale gas reservoir potential using multi-scaled SEM pore network characterizations and quantifications: The Ciñera-Matallana pull-apart basin, NW Spain". Stratigraphy & Timescales. 5: 677–755. doi:10.1016/bs.sats.2020.07.001. ISBN 9780128209912. S2CID 229217907 – via Elsevier Science Direct.

- Dan Jarvie, "Worldwide shale resource plays," PDF file, NAPE Forum, 26 August 2008.

- US Department of Energy, "Modern shale gas development in the United States," April 2009, p.17.

- Dang, Wei; Zhang, Jinchuan; Nie, Haikuan; Wang, Fengqin; Tang, Xuan; Wu, Nan; Chen, Qian; Wei, Xiaoliang; Wang, Ruijing (2020). "Isotherms, thermodynamics and kinetics of methane-shale adsorption pair under supercritical condition: implications for understanding the nature of shale gas adsorption process". Chemical Engineering Journal. 383: 123191. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2019.123191. S2CID 208751235.

- US Energy Information Administration, North America leads the world in production of shale gas, 23 October 2013.

- A Comparison between Shale Gas in China and Unconventional Fuel Development in the United States: Water, Environmental Protection, and Sustainable Development, Farah, Paolo Davide; Tremolada, Riccardo in Brooklyn Journal of International Law, Vol. 41, No. 2, 2016, June 2016.

- China's Coming Decade of Natural Gas?, Damien Ma in Asia's Uncertain LNG Future, The National Bureau of Asian Research, November 2013.

- "Technically Recoverable Shale Oil and Shale Gas Resources: An Assessment of 137 Shale Formations in 41 Countries Outside the United States". Analysis and projections. United States Energy Information Administration. 13 June 2013.

- " Technically recoverable resources represent the volumes of oil and natural gas that could be produced with current technology, regardless of oil and natural gas prices and production costs. Technically recoverable resources are determined by multiplying the risked in-place oil or natural gas by a recovery factor."

- US Energy Information Administration, World Shale Gas Resources, Apr. 2011.

- "What's The Difference Between Wet And Dry Natural Gas?". Stateimpact.npr.org. Retrieved 13 January 2014.

- What Makes Wet Gas Wet?

- Morton, Michael Quentin (9 December 2013). "Unlocking the Earth: A Short History of Hydraulic Fracturing". GeoExpro. 10 (6). Retrieved 27 February 2014.

- "Market report on Shale Gas Market Industry now available". Market Report. Absolute Reports. 1 February 2016. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- "EIA studies won't be required for shale gas exploration". The Lithuania Tribune. 24 December 2013. Archived from the original on 31 December 2013. Retrieved 31 December 2013.

- Council of Scientific Society Presidents, , letter to President Obama, 4 May 2009.

- Environmental Protection Agency "Greenhouse Gas Emissions Reporting from the Petroleum and Natural Gas Industry, Background Technical Support Document, posted to web 30 November 2010.

- Shindell, D. T.; Faluvegi, G.; Koch, D. M.; Schmidt, G. A.; Unger, N.; Bauer, S. E. (30 October 2009). "Improved Attribution of Climate Forcing to Emissions". Science. 326 (5953): 716–718. Bibcode:2009Sci...326..716S. doi:10.1126/science.1174760. PMID 19900930. S2CID 30881469.

- Trembath, Alex; Luke, Max; Shellenberger, Michael; Nordhaus, Ted (June 2013). "Coal Killer: How Natural Gas Fuels the Clean Energy Revolution" (PDF). Breakthrough institute. p. 22. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 October 2013. Retrieved 2 October 2013.

- Howarth, RW; Santoro, R; Ingraffea, A (2011). "Methane and the greenhouse-gas footprint of natural gas from shale formations". Climatic Change. 106 (4): 679–690. Bibcode:2011ClCh..106..679H. doi:10.1007/s10584-011-0061-5.

- Timothy J. Skone, "Life Cycle Greenhouse Gas Analysis of Natural Gas Extraction & Delivery in the United States." National Energy Technology Laboratory, 12 May 2011

- Jiang, Mohan (2011). "Life cycle greenhouse gas emissions of Marcellus shale gas". Environmental Research Letters. 6 (3): 034014. Bibcode:2011ERL.....6c4014J. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/6/3/034014.

- Hultman, Nathan (2011). "The greenhouse impact of unconventional gas for electricity generation". Environmental Research Letters. 6 (4): 044008. Bibcode:2011ERL.....6d4008H. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/6/4/044008.

- Dan Lashof, "Natural Gas Needs Tighter Production Practices to Reduce Global Warming Pollution," 12 April 2011 "Natural Gas Needs Tighter Production Practices to Reduce Global Warming Pollution | Dan Lashof's Blog | Switchboard, from NRDC". Archived from the original on 13 January 2012. Retrieved 9 January 2012.

- Cathles, Lawrence M. (2012). "A commentary on "The greenhouse-gas footprint of natural gas in shale formations" by R.W. Howarth, R. Santoro, and Anthony Ingraffea". Climatic Change. 113 (2): 525–535. Bibcode:2012ClCh..113..525C. doi:10.1007/s10584-011-0333-0.

- "The Associated Press. "EPA lowered estimates of methane leaks during natural gas production"(The Houston Chronicle)". Fuelfix.com. 28 April 2013. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- "U.S. Greenhouse Gas Inventory Report". United States Environmental Protection Agency. 12 August 2013. Retrieved 2 October 2013.

- "5 Reasons Why It's Still Important To Reduce Fugitive Methane Emissions". World Resources Institute. Retrieved 2 October 2013.

- Stamford, Laurence; Azapagic, Adisa (2014). "Life cycle environmental impacts of UK shale gas". Applied Energy. 134: 506–518. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2014.08.063.

- Gao, Jiyao; You, Fengqi (2018). "Integrated Hybrid Life Cycle Assessment and Optimization of Shale Gas". ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering. 6 (2): 1803–1824. doi:10.1021/acssuschemeng.7b03198.

- Man Uni News article

- Frackland

- Kijk magazine, 2/2012

- Griswold, Eliza (17 November 2011). "The Fracturing of Pennsylvania". The New York Times.

- Brino, Anthony. "Shale gas fracking without water and chemicals". Dailyyonder.com. Archived from the original on 4 March 2012. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- Energy Policy Act of 2005. Pub. L. 109-58, TITLE III, Subtitle C, SEC. 322. Hydraulic fracturing. 6 February 2011

- Richard A. Kerr (13 May 2011). "Study: High-Tech Gas Drilling Is Fouling Drinking Water". Science Now. 332 (6031): 775. doi:10.1126/science.332.6031.775. Archived from the original on 13 May 2011. Retrieved 27 June 2011.

- "EPA: Natural Gas Drilling May Contaminate Drinking Water". Redorbit.com. 25 June 2011. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- Gruver, Mead (8 December 2011). "EPA theorizes fracking-pollution link". Associated Press. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- "Governor Mead: Implications of EPA Data Require Best Science".

- "EPA report: Pavillion water samples improperly tested".

- MIT Energy Initiative (2011). "The Future of Natural Gas: An Interdisciplinary MIT Study" (PDF). MIT Energy Initiative: 7,8. Retrieved 29 July 2011.

- "Terri White. U.S. EPA. "EPA Completes Drinking Water Sampling in Dimock, Pa."". Yosemite.epa.gov. 25 July 2012. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- Carus, Felicity (2 October 2013). "Dangerous levels of radioactivity found at fracking waste site in Pennsylvania". theguardian.com. Retrieved 9 October 2013.

- Warner, Nathaniel R.; Christie, Cidney A.; Robert B., Jackson; Avner, Vengosh (2 October 2013). "Impacts of Shale Gas Wastewater Disposal on Water Quality in Western Pennsylvania". Environmental Science and Technology. 47 (20): 11849–57. Bibcode:2013EnST...4711849W. doi:10.1021/es402165b. hdl:10161/8303. PMID 24087919. S2CID 17676293.

- US Environmental Protection Agency, Natural Gas Drilling in the Marcellus Shale, NPDES Program Frequently Asked Questions, Attachment to memorandum from James Hanlon, Director of EPA’s Office of Wastewater Management to the EPA regions, 16 March 2011.

- Les Bennett and others, "The Source for Hydraulic Fracture Characterization Archived 25 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine," Schlumberger, Oilfield Review, Winter 2005/2006, p.42–57

- US Geological Survey, How is hydraulic fracturing related to earthquakes and tremors?, accessed 20 April 2013.

- "シェールガス採掘、地震誘発?米中部、M3以上6倍" [Magnitude 3 and greater earthquakes 6 fold in the midcontinent of the United States. Beginning in 200. extracted shale gas induce earthquakes ?]. Asahi Shimbun (in Japanese). Tokyo. 26 April 2012. p. Page 1. Archived from the original on 23 July 2012. Retrieved 26 April 2012.

- Is the Recent Increase in Felt Earthquakes in the Central U.S. Natural or Manmade? United States Geological Survey, 11 April 2012

- "U.S. Senate Committee on Energy, Washington, D.C." Energy.senate.gov. 19 June 2012. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- Markandya, Anil; Wilkinson, Paul (15 September 2007). "Electricity Generation and Health". The Lancet. 370 (9591): 979–90. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61253-7. PMID 17876910. S2CID 25504602. Retrieved 2 October 2013.

- "Injuries, Illnesses, and Fatalities in the Coal Mining Industry". United States Bureau of Labor Statistics. Retrieved 2 October 2013.

- Keating, Martha; Baum, Ellen; Hennen, Amy (June 2001). "Cradle to Grave: The Environmental Impacts from Coal" (PDF). Clean Air Task Force. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 October 2013. Retrieved 2 October 2013.

- "Hidden Costs of Energy: Unpriced Consequences of Energy Production and Use" (PDF). National Research Council Committee on Health, Environmental, and Other External Costs and Benefits of Energy Production and Consumption. October 2009. Retrieved 2 October 2013.

- Jaramillo, Paulina; Griffin, W. Michael; Matthews, H. Scott (25 July 2007). "Comparative Life-Cycle Air Emissions of Coal, Domestic Natural Gas, LNG, and SNG for Electricity Generation" (PDF). Environmental Science & Technology. 41 (17): 6290–6296. Bibcode:2007EnST...41.6290J. doi:10.1021/es063031o. PMID 17937317. Retrieved 2 October 2013.

- Moomaw, W., P. Burgherr, G. Heath, M. Lenzen, J. Nyboer, A. Verbruggen, 2011: Annex II: Methodology. In IPCC: Special Report on Renewable Energy Sources and Climate Change Mitigation

- David Wogan, "When, not if, China taps into shale gas", Scientific American, 30 October 2013.

- Measham, Thomas G.; Fleming, David A.; Schandl, Heinz (January 2016). "A conceptual model of the socioeconomic impacts of unconventional fossil fuel extraction" (PDF). Global Environmental Change. 36: 101–110. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2015.12.002. ISSN 0959-3780.

- Weber, Jeremy G. (1 September 2012). "The effects of a natural gas boom on employment and income in Colorado, Texas, and Wyoming". Energy Economics. 34 (5): 1580–1588. doi:10.1016/j.eneco.2011.11.013. ISSN 0140-9883. S2CID 54920467.

- Fleming, David A.; Measham, Thomas G. (2015). "Local economic impacts of an unconventional energy boom: the coal seam gas industry in Australia" (PDF). Australian Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics. 59 (1): 78–94. doi:10.1111/1467-8489.12043. ISSN 1467-8489. S2CID 96439984.

- Marcos–Martinez, Raymundo; Measham, Thomas G.; Fleming-Muñoz, David A. (2019). "Economic impacts of early unconventional gas mining: Lessons from the coal seam gas industry in New South Wales, Australia". Energy Policy. 125: 338–346. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2018.10.067. S2CID 158594219.

- Measham, Thomas G.; Fleming, David A. (1 October 2014). "Impacts of unconventional gas development on rural community decline". Journal of Rural Studies. 36: 376–385. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2014.04.003. ISSN 0743-0167.

- Kay, David L.; Jacquet, Jeffrey (25 April 2014). "The Unconventional Boomtown: Updating the impact model to fit new spatial and temporal scales". Journal of Rural and Community Development. 9 (1). ISSN 1712-8277.

- Measham, Thomas G.; Walton, Andrea; Graham, Paul; Fleming-Muñoz, David A. (1 October 2019). "Living with resource booms and busts: Employment scenarios and resilience to unconventional gas cyclical effects in Australia". Energy Research & Social Science. 56: 101221. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2019.101221. ISSN 2214-6296. S2CID 198829712.

- Schneider, Conrad; Banks, Jonathan (September 2010). "The Toll From Coal: An Updated Assessment of Death and Disease From America's Dirtiest Energy Source" (PDF). Clean Air Task Force. Retrieved 2 October 2013.

- Brian Lutz, Hydraulic Fracturing versus Mountaintop-Removal Coal Mining: Comparing Environmental Impacts, University of Tulsa, 28 November 2012.

- Denholm, Paul; Hand, Maureen; Jackson, Maddalena; Ong, Sean (August 2009). "Land-Use Requirements of Modern Wind Power Plants in the United States" (PDF). National Renewable Energy Laboratory. Retrieved 2 October 2013.

- Moran, Matthew D. (2015). "Habitat Loss and Modification Due to Gas Development in the Fayetteville Shale". Environmental Management. 55 (6): 1276–1284. Bibcode:2015EnMan..55.1276M. doi:10.1007/s00267-014-0440-6. PMID 25566834. S2CID 36628835.

- "Guidance for the Comanagement of Mill Rejects at Coal-Fired Power Plants, Final Report". Electric Power Research Institute. June 1999. Retrieved 2 October 2013.

- Gleick, Peter H. (16 January 2014). The World's Water Volume 8: The Biennial Report on Freshwater Resources. Island Press. ISBN 9781610914833.

- Gao, Jiyao; You, Fengqi (2017). "Design and optimization of shale gas energy systems: Overview, research challenges, and future directions". Computers & Chemical Engineering. 106: 699–718. doi:10.1016/j.compchemeng.2017.01.032.

- Mielke, Erik; Diaz Anadon, Laura; Narayanamurti, Venkatesh (October 2010). "Water Consumption of Energy Resource Extraction, Processing, and Conversion" (PDF). Energy Technology Innovation Policy Research Group, Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, Harvard Kennedy School. Retrieved 2 October 2013.

- Fthenakis, Vasilis; Kim, Hyung Chul (September 2010). "Life-cycle uses of water in US electricity generation". Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 14 (7): 2039–2048. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2010.03.008.

- A. Torcellini, Paul; Long, Nicholas; D. Judkoff, Ronald (December 2003). "Consumptive Water Use for U.S. Power Production" (PDF). National Renewable Energy Laboratory. Retrieved 2 October 2013.

- Grubert, Emily A.; Beach, Fred C.; Webber, Michael E. (8 October 2012). "Can switching fuels save water?". Environmental Research Letters. 7 (4): 045801. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/7/4/045801.

- Jesse Jenkins, Friday Energy Facts: How Much Water Does Fracking for Shale Consume?, The Energy Collective, 5 April 2013.

- Futura. "Exploitation du gaz de schiste : quels dangers ?". Futura (in French). Retrieved 2 December 2017.

- Simon Mauger; Dana Bozbiciu (2011). "How Changing Gas Supply Cost Leads to Surging Production" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 December 2011. Retrieved 10 May 2011.

- US Energy Information Administration, Pad drilling and rig mobility lead to more efficient drilling, 11 September 2012.

- Ian Urbina (25 June 2011). "Insiders Sound an Alarm Amid a Natural Gas Rush". The New York Times. Retrieved 26 June 2011.

- Mazur, Karol (3 September 2012) Economics of Shale Gas EnergyCentral, Accessed 30 December 2020

- Gloyston, Henning and Johnstone, Christopher (17 April 2012) Exclusive – UK has vast shale gas reserves, geologists say Reuters Edition UK, Accessed 17 April 2012

- Suzanne Goldenberg in Barnhart, Texas (11 August 2013). "A Texan tragedy: ample oil, no water". Theguardian.com. Retrieved 13 January 2014.

- The Shale Gas Market Report 2011-2021 Archived 23 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine – visiongain

- Urbina, Ian (25 June 2011). "Insiders Sound an Alarm Amid a Natural Gas Rush". New York Times. Retrieved 28 June 2011.; Urbina, Ian (27 June 2011). "S.E.C. Shift Leads to Worries of Overestimation of Reserves". New York Times. Retrieved 28 June 2011.

- Arthur S. Brisbane, "Clashing views on the future of natural gas," New York Times, 16 July 2001.

- Caudillo, Yvonne. "" pp1+19-22. United States Department of Energy. Retrieved: 25 August 2012.

- Philips, Matthew. "Strange Bedfellows Debate Exporting Natural Gas", BusinessWeek 22 August 2012. Retrieved: 25 August 2012.

- Thiemo Fetzer (28 March 2014). "Fracking Growth". Retrieved 9 April 2014.

- EIA (17 February 2011). "Pipeline constraints raise average spot natural gas prices in the Northeast this winter". Retrieved 9 April 2014.

- "How Much Does a Shale Gas Well Cost? 'It Depends'", Breaking Energy, 6 August 2013

- What is the real cost of shale gas? by Euan Mearns, Oil Voice, 10 December 2013. Mearns cites data from Bloomberg and Credit Suisse.

- Conversions "$ per MM [million] Btu multiplied by 1.025 = $ per Mcf"

Further reading

- Gamper-Rabindran, Shanti, ed. The Shale Dilemma: A Global Perspective on Fracking and Shale Development (U of Pittsburgh Press, 2018) online review

External links

- Unconventional Gas and Implications for the LNG Market by Christopher Gascoyne and Alexis Aik. This is a working paper written for the 2011 Pacific Energy Summit hosted by the National Bureau of Asian Research.

- The Shale Gas Boom: The global implications of the rise of unconventional fossil energy, FIIA Briefing Paper 122, 20 March 2013, The Finnish Institute of International Affairs.

- A Comparison between Shale Gas in China and Unconventional Fuel Development in the United States: Health, Water and Environmental Risks by Paolo Farah and Riccardo Tremolada. This is a paper presented at the Colloquium on Environmental Scholarship 2013 hosted by Vermont Law School (11 October 2013)

- Map of Assessed Shale Gas in the United States, 2012 United States Geological Survey

- Registry will Help Study Health Impact from Living Near Shale Gas Wells, Birth Defect Research for Children Newsletter, May 2017