Siege of Byzantium (324)

The siege of Byzantium was carried out sometime between July and September 324 by the forces of the Roman emperor Constantine I (r. 306–337) during his Second Civil War against his rival, co-emperor Licinius (r. 308–324). It would have been started simultaneously with the naval battle of the Hellespont (today known as Dardanelles) in which Constantine's son and caesar Crispus (r. 317–326) defeated the Lycinian navy commanded by Admiral Abanto.

| Siege of Byzantium | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Civil wars of the Tetrarchy | |||||||

Left: bust of Licinius in Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna; right: head of the colossal statue of Constantine I in the Palazzo dei Conservatori, Rome. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Constantine I | Licinius | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Constantine the Great | Licinius | ||||||

The victory on the Hellespont made it possible to prolong the siege of Byzantium and forced Licinius to summon the forces that were quartered in the city to Asia Minor, where the emperor intended to regroup his remaining forces to confront Constantine again. However, he would be defeated at the consecutive battle of Chrysopolis, ending the Tetrarchy system and allowing the Constantine to establish himself as sole ruler of the Roman Empire.

This was the tenth significant siege of the city, and there were to be many more.

Background

Constantine had defeated Licinius in a previous war eight years earlier at the Battles of Cibalae and Campus Mardiensis. Peace was quickly arranged after this, in which Constantine conquered all of the Balkan Peninsula, with the exception of Thrace,[1] and placed himself in a superior position to Licinius, leaving an unstable relationship between them. As early as 323, Constantine was ready to renew the conflict, and when his army, which was chasing an invading band of Visigoths (or Sarmatians), crossed the border into Licinius' territory, a timely casus belli was present. Licinius' reaction to the trespassing was entirely hostile, which spurred Constantine to continue on the offensive. He invaded Thrace with all his strength and, although his group was smaller than that of Licinius, it was filled with battle veterans. Furthermore, since Illyria was under his control, he had access to the best recruits in the empire.[2]

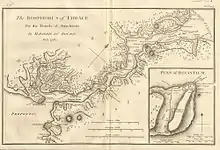

After his defeat at the Battle of Adrianople (324), Licinius and his main army retreated to the city of Byzantium (currently Istanbul, Turkey). He left a strong garrison there and crossed the Bosphorus Strait with most of his troops. To maintain his strength in Byzantium and to secure his line of communication between the capital and his army in Asia Minor, maintaining control of the straits that separated Thrace from Bithynia (Bosphorus) and Mysia (Hellespont) became imperative for Licinius.[3]

To cross into Asia to overcome Licinius' resistance, Constantine would also have to gain maritime control of the straits. Licinius' main army was on the Bosphorus to guard it while the majority of his navy moved to cover the Hellespont. He also assembled a second force under his newly elevated co-emperor Martinian (r. 324) at Lampsacus (present-day Lapseki) on the Asiatic coast of the Hellespont.[3]

Siege and aftermath

While Crispus (r. 317-326), was ordered to lead the Constantinian fleet toward the Hellespont, to blockade the Lycinian fleet,[4] the emperor was leading the siege of Byzantium.[5] Constantine began the siege by building an embankment as high as the city walls. He then made use of battering rams and other siege weapons, and erected some wooden towers on the embankment so that he could capture the city without too many casualties. Archers were placed in the towers so that they could attack the defenders.[6]

In the meantime, Crispus was able to annihilate the Lycinean navy, allowing more supplies to reach his father's army, ensuring that the siege progressed. Licinius, not knowing how to deal with the military pressure he was under, abandoned Byzantium and left the weakest part of his army inside the city. He took refuge in Chalcedon, in Bithynia,[6] and regrouped his remaining forces to try to oppose the emperor.[7] Constantine, in turn, headed with most of his troops to Anatolia and confronted his rival at the Battle of Chrysopolis, where he would win a decisive victory. Byzantium and Chalcedon yielded, and Licinius was forced to flee with his remaining soldiers to Nicomedia,[8] but yielded some time later.[9]

See also

References

- Odhal (2004). Constantine and the Christian Empire. p. 164.

- Grant (1998). The Emperor Constantine. p. 45.

- Lieu (1996). From Constantine to Julian: Pagan and Byzantine Views: A Source History. pp. 47, 60.

- Ridley (1982). "II.24.2". Zosimus: New History.

- Ridley (1982). "II.23.1; 24.2". Zosimus: New History.

- Ridley (1982). "II.25.1". Zosimus: New History.

- Ridley (1982). "II.25.2". Zosimus: New History.

- Ridley (1982). "II.25.3". Zosimus: New History.

- Grant (1985). The Roman emperors: a biographical guide to the rulers of Imperial Rome 31 BC-AD 276. pp. 46–48.

Bibliography

- Odahl, Charles Matson (2004). Constantine and the Christian empire. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-17485-6. OCLC 53434884

- 1914-2004., Grant, Michael, (1998). The Emperor Constantine. Phoenix Giant. ISBN 0-7538-0528-6. OCLC 43202670

- From Constantine to Julian: Pagan and Byzantine Views ; A Source History. Samuel N. C. Lieu, Dominic Montserrat. London: Routledge. 1996. ISBN 0-585-45312-8. OCLC 52730278.

- Ridley, Ronald T. (1982-01-01). Zosimus: New History. BRILL. ISBN 978-0-9593626-0-2.

- Grant, Michael (1985). The Roman emperors: a biographical guide to the rulers of Imperial Rome 31 BC-AD 276. London. ISBN 0-297-78555-9. OCLC 12474450.