Shamakhi

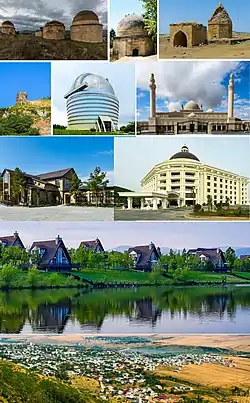

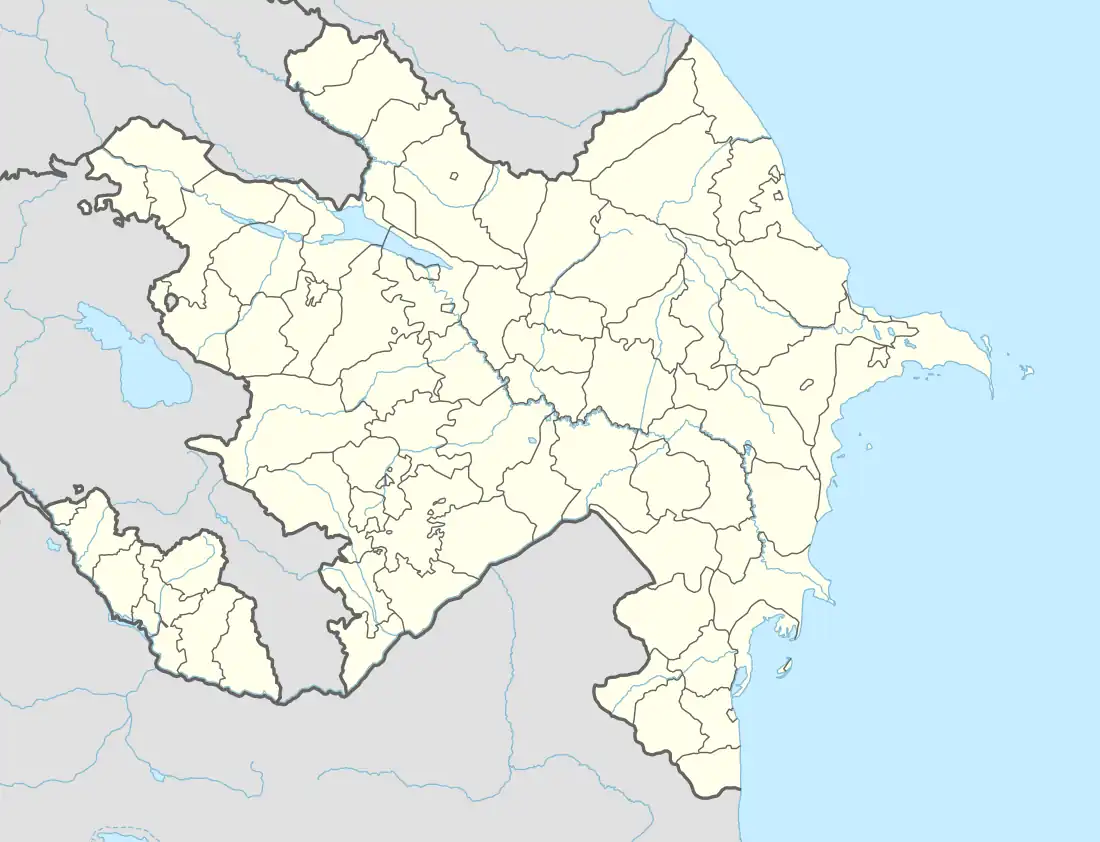

Shamakhi (Azerbaijani: Şamaxı, pronounced [ʃɑmɑˈxɯ]) is a city in Azerbaijan and the administrative centre of the Shamakhi District. The city's estimated population as of 2010 was 31,704.[1] It is famous for its traditional dancers, the Shamakhi Dancers, and also for perhaps giving its name to the Soumak rugs.[2]

Shamakhi

Şamaxı | |

|---|---|

City | |

| |

Shamakhi | |

| Coordinates: 40°37′49″N 48°38′29″E | |

| Country | |

| District | Shamakhi |

| Area | |

| • Total | 6 km2 (2 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 709 m (2,326 ft) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 31,704 |

| • Density | 5,300/km2 (14,000/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+4 (AZT) |

| Area code | +994 2026 |

Eleven major earthquakes have rocked Shamakhi but through multiple reconstructions, it maintained its role as the economic and administrative capital of Shirvan and one of the key towns on the Silk Road. The only building to have survived eight of the eleven earthquakes is the landmark Juma Mosque of Shamakhi, built in the 8th century.

History

Shamakhi was in antiquity part of successive Persian empires and was first mentioned as Kamachia by the ancient Greco-Roman Egyptian geographer Claudius Ptolemaeus in the 1st to 2nd century AD. Shamakhi was an important town during the Middle Ages and served as a capital of the Shirvanshah realm from the 8th to 15th centuries.

Shamakhi maintained economic and cultural relations with India and China in the 12th century, and the excavation of pottery containers prove that Shamakhi also had relations with the Central Asian cities at around the same time. Copper coins found in Shamakhi during archaeological excavations, porcelain containers produced in China, caravanserais serving international trade, prove the role of ancient Shamakhi in the Silk Road.[3]

The Catholic friar, missionary and explorer William of Rubruck passed through it on his return journey from the Mongol Great Khan's court.[4] In 1476 Venetian diplomat Giosafat Barbaro, while describing the city, stated: "This [Sammachi] is a good city; it has from four to five thousand houses, it produces silk, cotton as well as other things according to its tradition.".[5]

In 1500–1501, it was taken by the Safavid dynasty. Following the conquest of the area by the first Safavid ruler Ismail I, he allowed the descendants of Farrukh Yassar to rule Shamakhi and the rest of Shirvan under Safavid suzerainty. This lasted until 1538, when his son and successor, king Tahmasp I (r. 1524–1576), turned the territory into a full Safavid province and appointed its first Safavid governor.[6] From then on, Shamakhi functioned as the capital of the Shirvan province. In 1562 Englishman Anthony Jenkinson described the city in the following terms: "This city is five days' walk on camels from the sea, now it has fallen a lot; it is predominantly populated by Armenians..."[7][8]

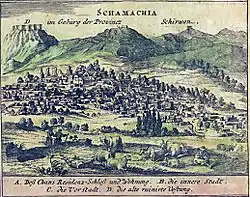

According to Carmelite monks who visited the city in 1607, its population was made up of Persians and Armenians. Armenians were actively engaged in trade. In addition to ordinary taxes, the Armenian people paid tribute to other religions.[9] Adam Olearius, who visited Shamakhi in 1637, wrote: "Its inhabitants are in part Armenians and Georgians, who have their particular language; they would not understand each other if they did not use Turkish, which is common to all and very familiar, not only in Shirvan, but also everywhere in Persia".[10] The Ottoman traveller Evliya Çelebi visited the town in 1647 and described it as having[11]

about 7,000 well built houses...26 quarters... seventy mosques...forty schools for boys, seven pleasant baths...forty caravanserais...the greatest part of the inhabitants are Sunnis of the Hanefirites, who perform their prayers secretly.

In the 1670s, the Spanish traveler Pedro Cobro Sebastian wrote that the inhabitants of Shamakhi were Persians, Armenians, and Georgians.[12] According to John Bell, an English tourist, Turkish was the common language of the people of 1715, but the city's elites spoke Persian and there were many Georgians and Armenians in the city.[13] The locals were mainly engaged in winemaking, animal husbandry and carpet weaving. In 1721, the Lezgins of the Safavid provinces of Shirvan and Dagestan, aided by the (rest of the) Sunni inhabitants of the area, sacked the city.[14][15] They massacred thousands of its Shia inhabitants, apart from looting the city and robbing the property of its Christian inhabitants and foreign nationals, the latter which were mostly the city's many Russian merchants.[14][15]

The Russian forces first entered Shirvan in 1723, as they invaded the Safavid Iranian territories in the North Caucasus and Transcaucasia during the Russo-Persian War (1722–1723), using the attack on their subjects in Shamakhi shortly before by the rebellious Lezgins as one of the pretexts.[16][17] They however soon retired from the city, leaving it to Ottomans who possessed it in 1723–35, until Nader Shahs rise. In 1742 Shamakhi was taken and destroyed by Nader Shah of Persia reincorporating it back to Iran, and, who, to punish the inhabitants for their Sunnite creed, built a new town under the same name about 26 kilometres (16 mi) to the west, at the foot of the main chain of the Caucasus Mountains. The new Shamakhi was at different times a residence of the Shirvan Khanate, ruled by semi-independent khans, but it was finally abandoned, and the old town rebuilt. In the mid-1700s, the population of Shamakhi was about 60,000, most of whom were Armenians. At this time it was one of the best and most populous cities of Persia, before it was destroyed by an earthquake.[18] The Shirvan Khanate was finally annexed by Russia in 1805 during the Russo-Persian War (1804–1813) and Qajar Iran was forced to irrevocably cede the sovereignty over the town to Russia, under the Treaty of Gulistan of 1813.

The British Penny Cyclopaedia stated in 1833 that "The bulk of the population of Shirvan consists of the Tahtar, or, to speak more correctly, Turkish race, with some admixture of Arabs and Persians. . . . Besides the Mohammedans, who form the mass of the population, there are many Armenians, some Jews, and a few Gipsies. According to the official returns of 1831, the number of males belonging to the Mohammedan population was 62,934; Armenians, 6,375; Jews, 332; total males 69,641. The prevalent language of Shirvan is what is there called Toorkee or Turkish, which is also used in Azerbijan". The same source also states that according to the official returns of 1832, the city of Shamakhi was inhabited by only 2,233 families, as a result of devastation from the sack of the city "in the most barbarous manner by the highlanders of Daghestan" in 1717.[19] The Encyclopædia Britannica stated that in 1873 the city had 25,087 inhabitants, "of which 18,680 were Tartars and Shachsevans, 5,177 were Armenians, and 1,230 Russians". Silk production continued to be the main output, with 130 silk-winding establishments, owned mostly by Armenians, although the industry had considerably declined since 1864.[20]

Shamakhi was the capital of the Shemakha uezd of the Shemakha Governorate of the Russian Empire until the devastating earthquake of 1859, when the capital of the province was transferred to Baku. The importance of the city declined sharply afterwards. According to the Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary (vol. 77, p. 460, published in 1903), Shamakhi had 20,008 inhabitants (10,450 males and 9,558 females), of which 3% were Russians, 18% were Armenians, and 79% "Azerbaijani Tatars" (later known as Azerbaijanis). With regard to religion, 79% of the population was Muslim, of which 22% was Sunni and the rest Shia; the remaining 21% was Armenian Apostolic and Eastern Orthodox.[21]

Weaving and rug making in Shamakhi

Historically, Shamakhi was famous for its carpets of which decoration using the buta motif dominate as with other Shirvan carpets. Shirvan carpets are on display at some of the world's famous museums. Example of these are Shirvan (13th century) kept in Istanbul's Turkish and Islamic museum, Shirvan (15th century), kept in the East Region of the Berlin Art Museum, and Shamakhi (17th century) carpets kept in the Pennsylvania Museum of America.[22]

Other artistic products include copper craft, pottery, tailoring, jewellery, woodworking, sculpture, and blacksmithery (blacksmiths were very popular in Alsahab). also developed in Shamakhi.[3]

Geography

Seismicity

The city is located in the most seismic area of the Caucasus and was hit by powerful earthquakes in 1191 and 1859, which was so destructive that the capital of Shirvan was transferred to Baku twice.[23] In 1872, the earthquake triggered emigration to Baku, where oil production had started in industrial proportions.

The 1667 earthquake is considered to have been the worst with a death toll of 80,000, with one-third of the city collapsed, according to the Persian merchants' reports.[24] The last catastrophic earthquake was recorded in 1902, which destroyed the 10th-century Juma Mosque.[25] Shamakhi is near the boundary of three plates.

Rivers

Shamakhi is located in the central part of Shirvan, at an altitude of about 749 m (2,457 ft) above sea level, in a favorable geographical position. In the south of Shamakhi flows to Zongalavay, and in the east Pirsaatchay. The city is surrounded by Binasli, Gushhan from the north, Pirdiraki, and Maiden Tower-Georgia from north-west and Meysari Mountains from the west. These mountains can be considered as the city's natural defense fortifications. There are many springs that provide urban population and people of surrounding villages with drinking water because of located at the slopes of the Caucasus Mountains.[3]

Climate

| Climate data for Shamakhi | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 3.7 (38.7) |

4.1 (39.4) |

8.2 (46.8) |

16.4 (61.5) |

21.2 (70.2) |

25.8 (78.4) |

29.8 (85.6) |

28.8 (83.8) |

24.2 (75.6) |

16.7 (62.1) |

10.7 (51.3) |

6.4 (43.5) |

16.3 (61.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −0.1 (31.8) |

0.6 (33.1) |

3.9 (39.0) |

10.8 (51.4) |

15.6 (60.1) |

19.9 (67.8) |

23.7 (74.7) |

22.8 (73.0) |

18.3 (64.9) |

11.1 (52.0) |

6.0 (42.8) |

2.6 (36.7) |

11.3 (52.3) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −3.0 (26.6) |

−2.5 (27.5) |

0.8 (33.4) |

6.7 (44.1) |

11.2 (52.2) |

15.4 (59.7) |

18.4 (65.1) |

17.6 (63.7) |

13.7 (56.7) |

8.1 (46.6) |

3.9 (39.0) |

−0.8 (30.6) |

7.5 (45.5) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 42 (1.7) |

45 (1.8) |

73 (2.9) |

69 (2.7) |

74 (2.9) |

54 (2.1) |

21 (0.8) |

19 (0.7) |

36 (1.4) |

73 (2.9) |

49 (1.9) |

40 (1.6) |

595 (23.4) |

| Average precipitation days | 8 | 10 | 12 | 8 | 9 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 9 | 8 | 7 | 88 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 103.1 | 92.5 | 112.8 | 179.7 | 211.8 | 258.7 | 279.4 | 252.8 | 211.8 | 152.3 | 110.7 | 113.7 | 2,079.3 |

| Source: NOAA[26] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

Ethnic groups

In 1607, Carmelite monks passing through the city reported population of Shamakhi consisting of mostly Turks and Armenians.[27] In the 1670s, the Spanish traveler Pedro Cubero Sebestian writes that the inhabitants of Shamakhi were Persians, Armenians and Georgians. However, during this period the term “Persians” was also applied to Turkic speakers. [28] In 1715, the English traveler John Bell wrote that the common language of the city's inhabitants was Turkic, but the city elite spoke Persian, and there were also a significant number of Georgians and Armenians.[29] According to the 1856 publication of Kavkazskiy kalendar, in Shamakhi—then known as Shemakha— 164 houses belonged to Russians, 469 to Armenians, 1160 to Sunni Muslims, 1320 to Shia Muslims.[30] According to the 1917 publication of Kavkazskiy kalendar Shamakhi had a population of 27,732 in 1916, including 14,811 men and 12,941 women, 27,259 of whom were the permanent population and 493 were temporary residents. Its ethnoreligous composition was as follows:[31]

| Nationality | Number | % |

|---|---|---|

| Shia Muslims | 12,522 | 45.12 |

| Sunni Muslims | 8,605 | 31.01 |

| Armenians | 4,534 | 16.34 |

| Russians | 1,737 | 6.26 |

| North Caucasians | 214 | 0.77 |

| Jews | 136 | 0.49 |

| Other Europeans | 4 | 0.01 |

| TOTAL | 27,752 | 100.00 |

The majority of the population is Azerbaijani, while Russians, Lezgins and Tats constitute other minorities. They speak the Azerbaijani language, Russian language, Lezgian language and Tat language respectively.

Religion

The Juma Mosque of Shamakhi is the biggest religious building in the city. Through its history the mosque has been demolished or destroyed few times, but each time it has been rebuilt, most recently in 2009.[32][33] It is the oldest mosque in the territory of Azerbaijan, and was built in 743–744. It is second in age in the South Caucasus after Derbent Juma mosque (built in 734). The mosque was registered by the Ministry of Culture and Tourism of the Republic of Azerbaijan as a historical and cultural monument of the country.

The mosque was restored several times in the Middle Ages Century during the Shamakhi earthquake in 1856 and 1902 was destroyed. First reconstructed was done by Gasim Hajibababayov and later by Iosif Ploško. The last restoration work at the mosque was carried out in 2010–2013.

Economy

After the Decree "On measures to accelerate socio-economic development in the Republic of Azerbaijan", signed by Ilham Aliyev on 24 November 2003 and the "State Program on Socio-Economic Development of the Regions of the Republic of Azerbaijan" approved by the head of state, began to increase living standards in Shamakhi along with other regions.[3]

Thus, at Shamakhi carpet shop where were installed 40 pieces of machine tools, which belongs to "Star" LTD, weave carpets such as "Guba-Shirvan", "Nakhchivan", "Garabagh" and "Tabriz". In 2005, at the Shamakhi TV Production Plant built by "Star" LTD, "Star" branded 37, 54, 72, 74 "LCD", "Plasma", "CV" and digital "Receivers" are produced based on spare parts of Toshiba "VCD".[34]"Star" LTD has invested $10 million in the construction of the AzSamand mini-car production plant.[34][35]

The building of the Historical-Ethnographic Museum named S.Shirvani was renovated and the bust of 12 great figures from the Shamakhi region was laid in the yard of the museum.

Culture

In the 19th century the town became famous due Shamakhi dancers, the principal dancers of the entertainment groups, similarly to tawaifs.[36] The city is home to Shirvan Domes, a 15th-century mausoleum and graveyard located at the foot of Gulistan Fortress.[37][38]

International relations

Twin towns and sister cities

Shamakhi is twinned with the following cities:

|

Notable residents

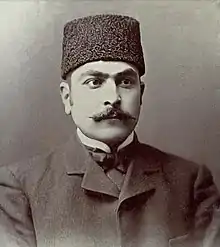

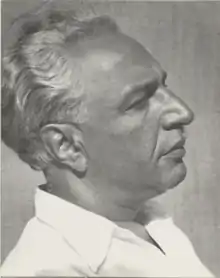

The city's notable residents include: philosopher Seyid Yahya Bakuvi, poets Seyid Azim Shirvani, Khaqani and Mirza Alakbar Sabir, mugham singers Alim Qasimov, Yaver Kelenterli and Farghana Qasimova, actors Aghasadyg Garaybeyli and Abbas Mirza Sharifzadeh, architect Gasim bey Hajibababeyov, Armenian playwright and novelist Alexander Shirvanzade and others.

Abbas Sahhat, one of prominent poets in Azerbaijani literature.

Abbas Sahhat, one of prominent poets in Azerbaijani literature.

Gostan Zarian, an Armenian writer and poet.

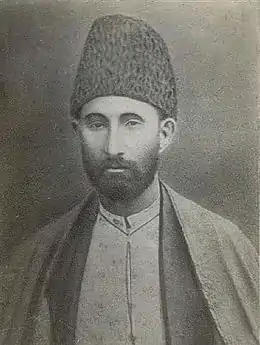

Gostan Zarian, an Armenian writer and poet. Seyid Azim Shirvani, continued Fuzûlî's traditions in his love-lyrical poems.

Seyid Azim Shirvani, continued Fuzûlî's traditions in his love-lyrical poems..jpg.webp)

Mirza Alakbar Sabir, one of the founders of the satirical trend in Azerbaijani literature.

Mirza Alakbar Sabir, one of the founders of the satirical trend in Azerbaijani literature.

Gallery

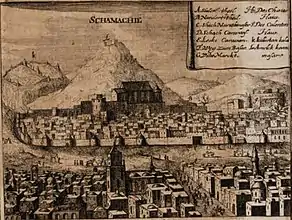

Şamaxı in 1656. From Adam Olearius book

Şamaxı in 1656. From Adam Olearius book Şamaxı in 1849

Şamaxı in 1849 Şamaxı female dancers by Grigory Gagarin, 1847

Şamaxı female dancers by Grigory Gagarin, 1847 Young Azeri girl from Şamaxı, 1883

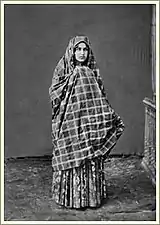

Young Azeri girl from Şamaxı, 1883 Azerbaijani woman from Şamaxı in the 19th century

Azerbaijani woman from Şamaxı in the 19th century Dancing in Şamaxı by Grigory Gagarin, 1840

Dancing in Şamaxı by Grigory Gagarin, 1840

Şamaxı pass in winter

Şamaxı pass in winter.jpg.webp) Shamakhi in 19th century

Shamakhi in 19th century Shamakhi in 19th century

Shamakhi in 19th century

See also

Notes

References

- Archived 6 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- "Soumac". Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 10 June 2014.

- "Şamaxı şəhərinin tarixi". Archived from the original on 3 August 2016.

- Yule, Henry; Beazley, Charles (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 23 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 810–811.

- Viaggi fatti da Vinetia, alla Tana, in Persia, in India, et in Costantinopoli: con la descrittione particolare di città, luoghi, siti, costumi et della Porta del gran Turco... (in Italian). nelle case de figlivoli di Aldo. 1543.

- Fisher et al. 1986, pp. 212, 245.

- Извѣстiя Англичанъ о Россiи во второй половинѣ XVI вѣка. Переводъ съ Англiйскаго, съ предисловiемъ С. М. Середонина, p. 63

- Richard Hakluyt (1972). Voyages and Discoveries (2nd ed.). London: Penguin Books Limited. pp. 91–101. ISBN 978-0-14-043073-8.

- E. A Kərimov (1964). "Rus elmində XV — XIX-in birinci rübündə Azərbaycanın etnoqrafiya tədqiqatının tarixindən". Azərbaycan etnoqrafiya toplusu. Bakı: Azərbaycan SSR EA Nəşriyyatı. pp. 202–204, 210, 217.

- [Adam Olearius. Relation du voyage de Adam Olearius en Moscovie, Tartarie et Perse..., vol. 1, traduit de l'allemand par A. de Wicquefort, Paris, 1666, pp. 405–406]

- Efendi, Evliya; Hammer (Translator), Joseph (1850). Narrative of Travels, Europe, Asia and Africa. London. p. 160.

{{cite book}}:|last2=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Willem Floor and Hasan Javadi, The Role of Azerbaijani Turkish in Safavid Iran.

- Willem Floor and Hasan Javadi, The Role of Azerbaijani Turkish in Safavid Iran, стр. 572.

- Fisher et al. 1991, p. 316.

- Axworthy 2010, p. 42.

- Axworthy 2010, p. 62.

- Matthee 2005, p. 28.

- "Shamaki, reckoned the capital of this province, stands on a river which falls into the Caspian sea, and is about sixty-six miles from Derbent towards the south, and ninety-two from Gangea to the south-east. This city was one of the best and most populous of Persia, before it was destroyed by an earthquake. It is, however, supposed to contain near 60,000 inhabitants, chiefly Armenians and strangers, whom the pleasantness of the country and traffic have invited thither" (An Universal History: From the Earliest Accounts to the Present Time, by George Sale, George Psalmanazar, Archibald Bower, George Shelvocke, John Campbell, John Swinton, vol. 43, London, 1765, p. 138)

- The Penny Cyclopædia of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge, vol. XI, London, 1833, pp. 174–175.

- The Encyclopædia Britannica, vol. 21, Philadelphia, 1894, p. 831, article "Shirvan".

- "Шемаха / Энциклопедия Брокгауза и Эфрона". gatchina3000.ru. Retrieved 4 February 2022.

- "The Develpoment of Carpet Weaving in Azerbaijan". 17 April 2015. Retrieved 18 July 2020.

- "Shamakhy Outlook". discoverazerbaijan.az. Archived from the original on 23 October 2013. Retrieved 11 November 2014.

- NGDC. "Comments for the Significant Earthquake". Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- "Shamakhi's seismic history". seismology.az. Retrieved 11 November 2014.

- "Samaxi Climate Normals 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- Willem Floor and Hasan Javadi, The Role of Azerbaijani Turkish in Safavid Iran, P. 570

- Willem Floor and Hasan Javadi, The Role of Azerbaijani Turkish in Safavid Iran,

In the 1670s the Spanish traveler Pedro Cubero Sebastián wrote that the inhabitants of Shamakhi were: «Persians, Armenians and Georgians». However, by that time the term Persians also included Turkic-speakers

- Willem Floor and Hasan Javadi, The Role of Azerbaijani Turkish in Safavid Iran, P. 572

- Kavkazskiy Kalendar 1856

- Кавказский календарь на 1917 год [Caucasian calendar for 1917] (in Russian) (72nd ed.). Tiflis: Tipografiya kantselyarii Ye.I.V. na Kavkaze, kazenny dom. 1917. Archived from the original on 4 November 2021.

- "Azərbaycan Prezidenti Şamaxı şəhərindəki Cümə məscidinin bərpası ilə əlaqədar tədbirlər haqqında sərəncam verib". Trend.az. Archived from the original on 30 November 2016. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- "Şamaxıdakı Cümə məscidi yenidən qurulur".

- ""Evsen" Group of Companies || Official web site". www.evsengroup.az.

- "Iranian official visits Azerbaijan's Shamakhi city". 2 May 2010. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- Ими восхищался Дюма by Emil Karimov and Mehpara Aliyeva. Azeri.ru

- "Shamakhi Travel Guide - Tours, Attractions and Things To Do". www.advantour.com. Retrieved 4 February 2022.

- "Tourism in Azerbaijan – Explore Azerbaijan and Cities". Retrieved 4 February 2022.

- "Azerbaijani mugham's history". ocaz.eu. Archived from the original on 13 November 2014. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- "Protocol signed about twin cities – Shamakhi and Igdir". www.today.az. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- "Azərbaycanın Şamaxı və İsrailin Tirat Karmel şəhərləri qardaşlaşıblar – FOTO". Milli.Az (in Azerbaijani). 6 September 2017. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- "Məhəmməd Hadi". azerbaijans.com.

Sources

- Axworthy, Michael (2010). The Sword of Persia: Nader Shah, from Tribal Warrior to Conquering Tyrant. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-0857721938.

- Fisher, William Bayne; Avery, P.; Hambly, G. R. G; Melville, C. (1986). The Cambridge History of Iran. Vol. 6. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521200943.

- Fisher, William Bayne; Avery, P.; Hambly, G. R. G; Melville, C. (1991). The Cambridge History of Iran. Vol. 7. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521200950.

- Matthee, Rudolph P. (2005). The Pursuit of Pleasure: Drugs and Stimulants in Iranian History, 1500–1900. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691118550.

Further reading

- Evliya Çelebi (1834). "Description of the Town of Shamakhi". Narrative of Travels in Europe, Asia, and Africa, in the Seventeenth Century. Vol. 2. Translated by Joseph von Hammer-Purgstall. London: Oriental Translation Fund.