Self-knowledge (psychology)

Self-knowledge is a term used in psychology to describe the information that an individual draws upon when finding answers to the questions "What am I like?" and "Who am I?".

| Part of a series on |

| The Self |

|---|

| Constructs |

| Theories |

| Processes |

| Value judgment |

| As applied to activities |

| Interpersonal |

| Social |

| Politics |

While seeking to develop the answer to this question, self-knowledge requires ongoing self-awareness and self-consciousness (which is not to be confused with consciousness). Young infants and chimpanzees display some of the traits of self-awareness[1] and agency/contingency,[2] yet they are not considered as also having self-consciousness. At some greater level of cognition, however, a self-conscious component emerges in addition to an increased self-awareness component, and then it becomes possible to ask "What am I like?", and to answer with self-knowledge, though self-knowledge has limits, as introspection has been said to be limited and complex.

Self-knowledge is a component of the self or, more accurately, the self-concept. It is the knowledge of oneself and one's properties and the desire to seek such knowledge that guide the development of the self-concept, even if that concept is flawed. Self-knowledge informs us of our mental representations of ourselves, which contain attributes that we uniquely pair with ourselves, and theories on whether these attributes are stable or dynamic, to the best that we can evaluate ourselves.

The self-concept is thought to have three primary aspects:

The affective and executive selves are also known as the felt and active selves respectively, as they refer to the emotional and behavioral components of the self-concept. Self-knowledge is linked to the cognitive self in that its motives guide our search to gain greater clarity and assurance that our own self-concept is an accurate representation of our true self; for this reason the cognitive self is also referred to as the known self. The cognitive self is made up of everything we know (or think we know) about ourselves. This implies physiological properties such as hair color, race, and height etc.; and psychological properties like beliefs, values, and dislikes to name but a few.

Relationship with memory

Self-knowledge and its structure affect how events we experience are encoded, how they are selectively retrieved/recalled, and what conclusions we draw from how we interpret the memory. The analytical interpretation of our own memory can also be called meta memory, and is an important factor of meta cognition.

The connection between our memory and our self-knowledge has been recognized for many years by leading minds in both philosophy[6] and psychology,[7][8] yet the precise specification of the relation remains a point of controversy.[9]

Specialized memory

- Studies have shown there is a memory advantage for information encoded with reference to the self.[10]

- Somatic markers, that is memories connected to an emotional charge, can be helpful or dysfunctional - there is a correlation but not causation, and therefore cannot be relied on.[11]

- Patients with Alzheimer's who have difficulty recognizing their own family have not shown evidence of self-knowledge.[12]

The division of memory

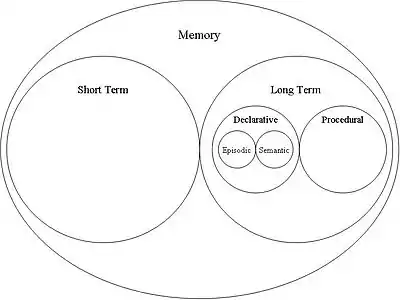

Self-theories have traditionally failed to distinguish between different source that inform self-knowledge, these are episodic memory and semantic memory. Both episodic and semantic memory are facets of declarative memory, which contains memory of facts. Declarative memory is the explicit counterpart to procedural memory, which is implicit in that it applies to skills we have learnt; they are not facts that can be stated.

Episodic memory

Episodic memory is the autobiographical memory that individuals possess which contains events, emotions, and knowledge associated with a given context.

Semantic memory

Semantic memory does not refer to concept-based knowledge stored about a specific experience like episodic memory. Instead it includes the memory of meanings, understandings, general knowledge about the world, and factual information etc. This makes semantic knowledge independent of context and personal information. Semantic memory enables an individual to know information, including information about their selves, without having to consciously recall the experiences that taught them such knowledge.

Semantic self as the source

People are able to maintain a sense of self that is supported by semantic knowledge of personal facts in the absence of direct access to the memories that describe the episodes on which the knowledge is based.

- Individuals have been shown to maintain a sense of self despite catastrophic impairments in episodic recollection. For example, subject W.J., who suffered dense retrograde amnesia leaving her unable to recall any events that occurred prior to the development of amnesia. However, her memory for general facts about her life during the period of amnesia remained intact.

- This suggests that a separate type of knowledge contributes to the self-concept, as W.J.'s knowledge could not have come from her episodic memory.[13]

- Evidence also exists that shows how patients with severe amnesia can have accurate and detailed semantic knowledge of what they are like as a person, for example which particular personality traits and characteristics they possess.[16][17]

This evidence for the dissociation between episodic and semantic self-knowledge has made several things clear:

- Episodic memory is not the only drawing point for self-knowledge, contrary to long-held beliefs. Self-knowledge must therefore be expanded to include the semantic component of memory.[18][19]

- Self-knowledge about the traits one possesses can be accessed without the need for episodic retrieval. This is shown through study of individuals with neurological impairments that make it impossible to recollect trait-related experiences, yet who can still make reliable and accurate trait-ratings of themselves, and even revise these judgements based on new experiences they cannot even recall.[20]

Motives that guide our search

People have goals that lead them to seek, notice, and interpret information about themselves. These goals begin the quest for self-knowledge. There are three primary motives that lead us in the search for self-knowledge:

- Self-enhancement

- Accuracy

- Consistency

Self-enhancement

Self-enhancement refers to the fact that people seem motivated to experience positive emotional states and to avoid experiencing negative emotional states. People are motivated to feel good about themselves in order to maximize their feelings of self-worth, thus enhancing their self-esteem.

The emphasis on feelings differs slightly from how other theories have previously defined self-enhancement needs, for example the Contingencies of Self-Worth Model.[21]

Other theorists have taken the term to mean that people are motivated to think about themselves in highly favorable terms, rather than feel they are "good".[22][23]

In many situations and cultures, feelings of self-worth are promoted by thinking of oneself as highly capable or better than one's peers. However, in some situations and cultures, feelings of self-worth are promoted by thinking of oneself as average or even worse than others. In both cases, thoughts about the self still serve to enhance feelings of self-worth.

The universal need is not a need to think about oneself in any specific way, rather a need to maximize one's feelings of self-worth. This is the meaning of the self enhancement motive with respect to self-knowledge.

Arguments

In Western societies, feelings of self-worth are in fact promoted by thinking of oneself in favorable terms.

- In this case, self-enhancement needs lead people to seek information about themselves in such a way that they are likely to conclude that they truly possess what they see as a positive defining quality.

See "Self-verification theory" section.

Accuracy

Accuracy needs influence the way in which people search for self-knowledge. People frequently wish to know the truth about themselves without regard as to whether they learn something positive or negative.[24] There are three considerations which underlie this need:[25]

- Occasionally people simply want to reduce any uncertainty. They may want to know for the sheer intrinsic pleasure of knowing what they are truly like.

- Some people believe they have a moral obligation to know what they are really like. This view holds particularly strong in theology and philosophy, particularly existentialism.

- Knowing what one is really like can sometimes help an individual to achieve their goals. The basic fundamental goal to any living thing is survival, therefore accurate self-knowledge can be adaptive to survival.[26]

Accurate self-knowledge can also be instrumental in maximizing feelings of self-worth.[27] Success is one of the number of things that make people feel good about themselves, and knowing what we are like can make successes more likely, so self-knowledge can again be adaptive. This is because self-enhancement needs can be met by knowing that one can not do something particularly well, thus protecting the person from pursuing a dead-end dream that is likely to end in failure.

Consistency

Many theorists believe that we have a motive to protect the self-concept (and thus our self-knowledge) from change.[28][29] This motive to have consistency leads people to look for and welcome information that is consistent with what they believe to be true about themselves; likewise, they will avoid and reject information which presents inconsistencies with their beliefs. This phenomenon is also known as self-verification theory. Not everyone has been shown to pursue a self-consistency motive;[30] but it has played an important role in various other influential theories, such as cognitive dissonance theory.[31]

Self-verification theory

This theory was put forward by William Swann of the University of Texas at Austin in 1983 to put a name to the aforementioned phenomena. The theory states that once a person develops an idea about what they are like, they will strive to verify the accompanying self-views.[32]

Two considerations are thought to drive the search for self-verifying feedback:[33]

- We feel more comfortable and secure when we believe that others see us in the same way that we see ourselves. Actively seeking self-verifying feedback helps people avoid finding out that they are wrong about their self-views.

- Self-verification theory assumes that social interactions will proceed more smoothly and profitably when other people view us the same way as we view ourselves. This provides a second reason to selectively seek self-verifying feedback.

These factors of self-verification theory create controversy when persons suffering from low-self-esteem are taken into consideration. People who hold negative self-views about themselves selectively seek negative feedback in order to verify their self-views. This is in stark contrast to self-enhancement motives that suggest people are driven by the desire to feel good about themselves.

Sources

There are three sources of information available to an individual through which to search for knowledge about the self:

- The physical world

- The social world

- The psychological world

The physical world

The physical world is generally a highly visible, and quite easily measurable source of information about one's self. Information one may be able to obtain from the physical world may include:

- Weight - by weighing oneself.

- Strength - by measuring how much one can lift.

- Height - by measuring oneself.

Limitations

- Many attributes are not measurable in the physical world, such as kindness, cleverness and sincerity.

- Even when attributes can be assessed with reference to the physical world, the knowledge that we gain is not necessarily the knowledge we are seeking. Every measure is simply a relative measure to the level of that attribute in, say, the general population or another specific individual.

- This means that any measurement only merits meaning when it is expressed in respect to the measurements of others.

- Most of our personal identities are therefore sealed in comparative terms from the social world.

The social world

The comparative nature of self-views means that people rely heavily on the social world when seeking information about their selves. Two particular processes are important:

- Social Comparison Theory[26]

- Reflected Appraisals

Social comparison

People compare attributes with others and draw inferences about what they themselves are like. However, the conclusions a person ultimately draws depend on whom in particular they compare themselves with. The need for accurate self-knowledge was originally thought to guide the social comparison process, and researchers assumed that comparing with others who are similar to us in the important ways is more informative.[34]

Complications of the social comparison theory

People are also known to compare themselves with people who are slightly better off than they themselves are (known as an upward comparison);[35] and with people who are slightly worse off or disadvantaged (known as a downward comparison).[36] There is also substantial evidence that the need for accurate self-knowledge is neither the only, nor most important factor that guides the social comparison process,[37] the need to feel good about ourselves affects the social comparison process.

Reflected appraisals

Reflected appraisals occur when a person observes how others respond to them. The process was first explained by the sociologist Charles H. Cooley in 1902 as part of his discussion of the "looking-glass self", which describes how we see ourselves reflected in other peoples' eyes.[38] He argued that a person's feelings towards themselves are socially determined via a three-step process:

"A self-idea of this sort seems to have three principled elements: the imagination of our appearance to the other person; the imagination of his judgment of that appearance; and some sort of self-feeling, such as pride or mortification. The comparison with a looking-glass hardly suggests the second element, the imagined judgment which is quite essential. The thing that moves us to pride or shame is not the mere mechanical reflection of ourselves, but an imputed sentiment, the imagined effect of this reflection upon another's mind." (Cooley, 1902, p. 153)

In simplified terms, Cooley's three stages are:[38]

- We imagine how we appear in the eyes of another person.

- We then imagine how that person is evaluating us.

- The imagined evaluation leads us to feel good or bad, in accordance with the judgement we have conjured.

Note that this model is of a phenomenological nature.

In 1963, John W. Kinch adapted Cooley's model to explain how a person's thoughts about themselves develop rather than their feelings.[39]

Kinch's three stages were:

- Actual appraisals - what other people actually think of us.

- Perceived appraisals - our perception of these appraisals.

- Self-appraisals - our ideas about what we are like based on the perceived appraisals.

This model is also of a phenomenological approach.

Arguments against the reflected appraisal models

Research has only revealed limited support for the models and various arguments raise their heads:

- People are not generally good at knowing what an individual thinks about them.[40]

- Felson believes this is due to communication barriers and imposed social norms which place limits on the information people receive from others. This is especially true when the feedback would be negative; people rarely give one another negative feedback, so people rarely conclude that another person dislikes them or is evaluating them negatively.

- Despite being largely unaware of how one person in particular is evaluating them, people are better at knowing what other people on the whole think.[41]

- The reflected appraisal model assumes that actual appraisals determine perceived appraisals. Although this may in fact occur, the influence of a common third variable could also produce an association between the two.

The sequence of reflected appraisals may accurately characterize patterns in early childhood due to the large amount of feedback infants receive from their parents, yet it appears to be less relevant later in life. This is because people are not passive, as the model assumes. People actively and selectively process information from the social world. Once a person's ideas about themselves take shape, these also influence the manner in which new information is gathered and interpreted, and thus the cycle continues.

The psychological world

The psychological world describes our "inner world". There are three processes that influence how people acquire knowledge about themselves:

Introspection

Introspection involves looking inwards and directly consulting our attitudes, feelings and thoughts for meaning. Consulting one's own thoughts and feelings can sometimes result in meaningful self-knowledge. The accuracy of introspection, however, has been called into question since the 1970s. Generally, introspection relies on people's explanatory theories of the self and their world, the accuracy of which is not necessarily related to the form of self-knowledge that they are attempting to assess.[42]

- A stranger's ratings about a participant are more correspondent to the participant's self-assessment ratings when the stranger has been subject to the participant's thoughts and feelings than when the stranger has been subject to the participant's behavior alone, or a combination of the two.[43]

Comparing sources of introspection. People believe that spontaneous forms of thought provide more meaningful self-insight than more deliberate forms of thinking. Morewedge, Giblin, and Norton (2014) found that the more spontaneous a kind of thought, the more spontaneous a particular thought, and the more spontaneous thought a particular thought was perceived to be, the more insight into the self it was attributed. In addition, the more meaning the thought was attributed, the more the particular thought influenced their judgment and decision making. People asked to let their mind wander until they randomly thought of a person to whom they were attracted to, for example, reported that the person they identified provided them with more self-insight than people asked to simply think of a person to whom they were attracted to. Moreover, the greater self-insight attributed to the person identified by the (former) random thought process than by the latter deliberate thought process led those people in the random condition to report feeling more attracted to the person they identified.[44]

Arguments against introspection

Whether introspection always fosters self-insight is not entirely clear. Thinking too much about why we feel the way we do about something can sometimes confuse us and undermine true self-knowledge.[45] Participants in an introspection condition are less accurate when predicting their own future behavior than controls[46] and are less satisfied with their choices and decisions.[47] In addition, it is important to notice that introspection allows the exploration of the conscious mind only, and does not take into account the unconscious motives and processes, as found and formulated by Freud.

Self-perception processes

Wilson's work is based on the assumption that people are not always aware of why they feel the way they do. Bem's self-perception theory[48] makes a similar assumption. The theory is concerned with how people explain their behavior. It argues that people don't always know why they do what they do. When this occurs, they infer the causes of their behavior by analyzing their behavior in the context in which it occurred. Outside observers of the behavior would reach a similar conclusion as the individual performing it. The individuals then draw logical conclusions about why they behaved as they did.

"Individuals come to "know" their own attitudes, emotions, and other internal states partially by inferring them from observations of their own overt behavior and/or the circumstances in which this behavior occurs. Thus, to the extent that internal cues are weak, ambiguous, or uninterpretable, the individual is functionally in the same position as an outside observer, an observer who must necessarily rely upon those same external cues to infer the individual's inner states." (Bem, 1972, p.2)

The theory has been applied to a wide range of phenomena. Under particular conditions, people have been shown to infer their attitudes,[49] emotions,[50] and motives,[51] in the same manner described by the theory.

Similar to introspection, but with an important difference: with introspection we directly examine our attitudes, feelings and motives. With self-perception processes we indirectly infer our attitudes, feelings, and motives by analyzing our behavior.

Causal attributions

Causal attributions are an important source of self-knowledge, especially when people make attributions for positive and negative events. The key elements in self-perception theory are explanations people give for their actions, these explanations are known as causal attributions.

Causal attributions provide answers to "Why?" questions by attributing a person's behavior (including our own) to a cause.[52]

People also gain self-knowledge by making attributions for other people's behavior; for example "If nobody wants to spend time with me it must be because I'm boring".

Activation

Individuals think of themselves in many different ways, yet only some of these ideas are active at any one given time. The idea that is specifically active at a given time is known as the Current Self-Representation. Other theorists have referred to the same thing in several different ways:

- The phenomenal self[53]

- Spontaneous self-concept[54]

- Self-identifications[55]

- Aspects of the working self-concept[56]

The current self-representation influences information processing, emotion, and behavior and is influenced by both personal and situational factors.

Self-concept

Self-concept, or how people usually think of themselves is the most important personal factor that influences current self-representation. This is especially true for attributes that are important and self-defining.

Self-concept is also known as the self-schema, made of innumerable smaller self-schemas that are "chronically accessible".[56]

Self-esteem

Self-esteem affects the way people feel about themselves. People with high self-esteem are more likely to be thinking of themselves in positive terms at a given time than people suffering low self-esteem.[57]

Mood state

Mood state influences the accessibility of positive and negative self-views.

When we are happy we tend to think more about our positive qualities and attributes, whereas when we are sad our negative qualities and attributes become more accessible.[58]

This link is particularly strong for people suffering low self-esteem.

Goals

People can deliberately activate particular self-views. We select appropriate images of ourselves depending on what role we wish to play in a given situation.[59]

One particular goal that influences activation of self-views is the desire to feel good.[60]

Social roles

How a person thinks of themselves depends largely on the social role they are playing. Social roles influence our personal identities.[61]

Social context and self-description

People tend to think of themselves in ways that distinguish them from their social surroundings.[62]

- The more distinctive the attribute, the more likely it will be used to describe oneself.

Distinctiveness also influences the salience of group identities.

- Self-categorization theory[63] proposes that whether people are thinking about themselves in terms of either their social groups or various personal identities depends partly on the social context.

- Group identities are more salient in the intergroup contexts.

Group size

The size of the group affects the salience of group-identities. Minority groups are more distinctive, so group identity should be more salient among minority group members than majority group members.

Group status

Group status interacts with group size to affect the salience of social identities.

Social context and self-evaluation

The social environment has an influence on the way people evaluate themselves as a result of social-comparison processes.

The contrast effect

People regard themselves as at the opposite end of the spectrum of a given trait to the people in their company.[64] However, this effect has come under criticism as to whether it is a primary effect, as it seems to share space with the assimilation effect, which states that people evaluate themselves more positively when they are in the company of others who are exemplary on some dimension.

- Whether the assimilation or contrast effect prevails depends on the psychological closeness, with people feeling psychologically disconnected with their social surroundings being more likely to show contrast effects. Assimilation effects occur when the subject feels psychologically connected to their social surroundings.[65]

Significant others and self-evaluations

Imagining how one appears to others has an effect on how one thinks about oneself.[66]

Recent events

Recent events can cue particular views of the self, either as a direct result of failure, or via mood.

- The extent of the effect depends on personal variables. For example people with high self-esteem do not show this effect, and sometimes do the opposite.[67]

Memory for prior events influence how people think about themselves.[68]

- Fazio et al. found that selective memory for prior events can temporarily activate self-representations which, once activated, guide our behavior.[69]

Deficiencies

Misperceiving

- Deficiency in knowledge of the present self.

- Giving reasons but not feelings disrupts self-insight.

Misremembering

- Deficiency of knowledge of the past self.

- Knowledge from the present overinforms the knowledge of the past.

- False theories shape autobiographical memory.

Misprediction

- Deficiency of knowledge of the future self.

- Knowledge of the present overinforms predictions of future knowledge.

- Affective forecasting can be affected by durability bias.

See also

References

- Gallup, G. G., Jr. (1979). Self-recognition in chimpanzees and man: A developmental and comparative perspective. New York: Plenum Press.

- Finkelstein, N. W., & Ramey, C. T. (1977). Learning to control the environment in infancy. Child Development, 48, 806–819.

- Stangor, Dr Charles (26 September 2014). "The Cognitive Self: The Self-Concept – Principles of Social Psychology – 1st International Edition". opentextbc.ca. Archived from the original on 2019-07-15. Retrieved 2019-10-16.

- Bandura, Albert; Caprara, Gian Vittorio; Barbaranelli, Claudio; Gerbino, Maria; Pastorelli, Concetta (2003). "Role of Affective Self-Regulatory Efficacy in Diverse Spheres of Psychosocial Functioning" (PDF). Child Development. 74 (3): 769–782. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.00567. PMID 12795389. S2CID 6671293. Archived from the original on 2020-12-01. Retrieved 2018-06-04.

- https://ac.els-cdn.com/S0010027715000256/1-s2.0-S0010027715000256-main.pdf?_tid=710543c7-e98f-4484-85e2-acf02e7076cc&acdnat=1528121667_89562a04b60eba34b74c91685e1508c9%5B%5D

- Locke, J. (1731). An essay concerning human understanding. London: Edmund Parker. (Original work published 1690)

- James, W. (1890). The principles of psychology (Vol. 1). New York: Holt.

- Kihlstrom, J. F., & Klein, S. B. (1994). The self as a knowledgeable structure. (As cited in Sedikedes, C., & Brewer, M. B. (Eds.), Individual self, relational self, collective self. (pp. 35–36). Philadelphia, PA: Psychology Press)

- Kihlstrom, J. F., & Klein, S. B. (1997). Self-knowledge and self-awareness. (As cited in Sedikedes, C., & Brewer, M. B. (Eds.), Individual self, relational self, collective self. (pp. 35–36). Philadelphia, PA: Psychology Press)

- Rogers, T. B., Kuiper, N. A., and Kirker, W. S. (1977). Self-reference and the encoding of personal information. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 35(9), 677–688

- Damasio, Antonio R., (2005). Descartes' Error: Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain. Penguin Books; Reprint edition

- Klein, S., Cosmides, L., & Costabile, K. (2003). Preserved knowledge of self in a case of Alzheimer's dementia. Social Cognition, 21(2), 157–165

- Klein, S. B., Loftus, J., & Kihlstrom, J. F. (1996). Self-knowledge of an amnesia patient: Toward a neuropsychology of personality and social psychology. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 125, 250–160

- Tulving, E. (1989). Remembering and knowing the past. American Scientist, 77, 361–367

- Tulving, E., Schacter, D. L., McLachlan, D. R., & Moscovitch, M. (1988). Priming of semantic autobiographical knowledge: A case study of retrograde amnesia. Brain and Cognition, 8, 3–20

- Klein, S. B., & Loftus, J. (1993). The mental representation of trait and autobiographical knowledge about the self. (As cited in Sedikedes, C., & Brewer, M. B. (Eds.), Individual self, relational self, collective self. (p. 36). Philadelphia, PA: Psychology Press)

- Klein, S. B., Chan, R. L., & Loftus, J. (1999). Independence of episodic and semantic self-knowledge: The case from autism. Social Cognition, 17, 413–436

- Cermack, L. S., & O'Connor, M. (1983). The anteriograde retrieval ability of a patient with amnesia due to encephalitis. Neuropsychologia, 21, 213–234

- Evans, J., Wilson, B., Wraight, E. P., & Hodges, J. R. (1993). Neuropsychological and SPECT scan findings during and after transient global amnesia: Evidence for the differential impairment of remote episodic memory. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry, 56, 1227–1230

- Klein, S. B., Kihlstrom, J. F., 7 Loftus, J. (2000). Preserved and impaired self-knowledge in amnesia: A case study. Unpublished manuscript.

- Crocker, J., & Wolfe, C. T. (2001). Contingencies of self-worth. Psychological Review, 108, 593–623

- Swann, W. B., Jr. (1990). To be adored or to be known? The interplay of self-enhancement and self-verification. (As cited in Brown, J. D. (1998). The self. USA: McGraw-Hill)

- Rosenburg, M. (1979). Conceiving the self. New York: Basic Books

- Trope, Y. (1986). Self-enhancement, self-assessment, and achievement behavior. (As cited in Brown, J. D. (1998). The self. USA: McGraw-Hill)

- Brown, J. D. (1991). Accuracy and bias in self-knowledge. (As cited in Brown, J. D. (1998). The self. USA: McGraw-Hill)

- Festinger, L. (1954). A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations, 7, 117–140

- Sedikedes, C., & Strube, M. J. (1997). Self-evaluation: To thine own self be good, to thine own self be sure, to thine own self be true, and to thine own self be better. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 29

- Epstein, S. (1980). The self-concept: A review and the proposal of an integrated theory of personality. (As cited in Brown, J. D. (1998). The self. USA: McGraw-Hill)

- Lecky, P. (1945). Self-consistency: A theory of personality. New York: Island Press

- Steele, C. M., & Spencer, S. J. (1992). The primacy of self-integrity. Psychological Enquiry, 3, 345–346

- Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Evanston, IL: Row Peterson

- Swann, W. B., Jr. (1983). Self-verification: Bringing social reality into harmony with the self. (As cited in Suls, J., & Greenwald, A. G. (Eds.), Social psychological perspectives on the self, 2, 33–66. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum)

- Swann, W. B., Jr., Stein-Seroussi, A., & Giesler, R. B. (1992). Why people self-verify. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 62, 392–401

- Wood, J. V. (1989). Theory and research concerning social comparisons of personal attributes. Psychological Bulletin, 106, 231–248

- Collins, R. L. (1996). For better or worse: The impact of upward social comparisons on self-evaluations. Psychological Bulletin, 119, 51–69

- Wills, T. A. (1981). Downward comparison principles in social psychology. Psychological Bulletin, 90, 245–271

- Helgeson, V. S., & Mickelson, K. D. (1995). Motives for social comparison. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 21, 1200–1209

- Cooley, C. H. (1902). Human nature and the social order. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons

- Kinch, J. W. (1963). A formalized theory of self-concept. American Journal of Sociology, 68, 481–486

- Felson, R. B. (1993). The (somewhat) social self: How others affect self-appraisals. (As cited in Brown, J. D. (1998). The self. USA: McGraw-Hill)

- Kenny, D. A., & DePaulo, B. M. (1993). Do people know how others view them? An empirical and theoretical account. Psychological Bulletin, 114, 145–161

- Nisbett, Richard E.; Wilson, Timothy D. (1977). "Telling more than we can know: Verbal reports on mental processes" (PDF). Psychological Review. 84 (3): 231–259. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.84.3.231. hdl:2027.42/92167.

- Andersen, S. M. (1984). Self-knowledge and social inference: II. The diagnosticity of cognitive/affective and behavioral data. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 46, 280–293

- Morewedge, Carey K.; Giblin, Colleen E.; Norton, Michael I. (2014). "The (perceived) meaning of spontaneous thoughts". Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 143 (4): 1742–1754. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.567.6997. doi:10.1037/a0036775. PMID 24820251. S2CID 36154815.

- Wilson, T. D., & Hodges, S. D. (1992). Attitudes as temporary constructions. (As cited in Brown, J. D. (1998). The self. USA: McGraw-Hill)

- Wilson, T. D., & LaFleur, S. J. (1995). Knowing what you'll do: Effects of analyzing reasons on self-prediction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68, 21–35

- Wilson, T. D., Lisle, D., Schooler, J., Hodges, S. D., Klaaren, K. J., & LaFleur, S. J. (1993). Introspecting about reasons can reduce post-choice satisfaction. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 19, 331–339

- Bem, D. J. (1972). Self-perception theory. (As cited in Brown, J. D. (1998). The self. USA: McGraw-Hill)

- Olson, J. M., & Hafer, C. L. (1990). Self-inference processes: Looking back and ahead. (As cited in Brown, J. D. (1998). The self. USA: McGraw-Hill)

- Laird, J. D. (1974). Self-attribution and emotion: The effects of expressive behavior on the quality of emotional experience. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 29, 475–486

- Lepper, M. R., Greene, D., & Nisbett, R. E. (1973). Undermining of children's intrinsic interest with extrinsic rewards: A test of the "overjustification" hypothesis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 28, 129–137

- Weiner, B. (1985). An attributional theory of achievement motivation and emotion. Psychological Review, 92, 548–573

- Jones, E. E., & Gerard, H. B. (1967). Foundations of social psychology. New York: Wiley

- McGuire, W. J., & McGuire, C. V. (1981). The spontaneous self-concept as affected by personal distinctiveness. (As cited in Brown, J. D. (1998). The self. USA: McGraw-Hill)

- Schlenker, B. R., & Weigold, M. F. (1989). Goals and the self-identification process: Constructing desired identities. (As cited in Brown, J. D. (1998). The self. USA: McGraw-Hill)

- Markus, H., & Kunda, Z. (1986). Stability and malleability of the self-concept. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 858–866

- Brown, J. D., & Mankowski, T. A. (1993). Self-esteem and self confidence are not the same. Self-esteem, mood, and self-evaluation: Changes in mood and the way you see you. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64, 421–430

- Sedikides, C. (1995). Central and peripheral self-conceptions are differentially influenced by mood: Tests of the different sensitivity hypothesis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69, 759–777

- Snyder, M. (1979). Self-monitoring processes (As cited in Brown, J. D. (1998). The self. USA: McGraw-Hill)

- Kunda, Z., & Santioso, R. (1989). Motivated changes in the self-concept. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 25, 272–285

- Roberts, B. W., & Donahue, E. M. (1994). One personality, multiple selves: Integrating personality and social roles. Journals of Personality, 62, 199–218

- Nelson, L. J., & Miller, D. T. (1995). The distinctiveness effect in social categorization: You are what makes you unusual. Psychological Science, 6, 246–249

- Turner, J. C., Hogg, M. A., Oakes, P. J., Reicher, S. D., & Wetherell, M. S. (1987). Rediscovering the social group: A self-categorization theory. Oxford, England: Basil Blackwell

- Morse, S., & Gergen, K. J. (1970). Social comparison, self-consistency, and the concept of the self. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 16, 148–156

- Brewer, M. B., & Weber, J. G. (1994). Self-evaluation effects of interpersonal versus intergroup social comparison. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 66, 268–275

- Baldwin, M. W. (1994). Primed relational schemas as a source of self-evaluative reactions. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 13, 380–403

- Brown, J. D., & Smart, S. A. (1991). The self and social conduct: Linking self-representations to prosocial behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60, 368–375

- Kunda, Z. (1990). The case for motivated reasoning. Psychological Bulletin, 108, 480–498

- Fazio, R. H., Effrein, E. A., & Falender, V. J. (1981). Self-perception following social interaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 41, 232–242

Further reading

- Brown, J. D. (1998). The self. New York: McGraw Hill. ISBN 0-07-008306-1

- Sedikides, C., & Brewer, M. B. (2001). Individual self, relational self, collective self. Philadelphia, PA: Psychology Press. ISBN 1-84169-043-0

- Suls, J. (1982). Psychological perspectives on the self (Vol. 1). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. ISBN 0-89859-197-X

- Sedikides, C., & Spencer, S. J. (Eds.) (2007). The self. New York: Psychology Press. ISBN 1-84169-439-8

- Thinking and Action: A Cognitive Perspective on Self-Regulation during Endurance Performance

External links

- Self-knowledge (psychology) at PhilPapers

- Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). "Self knowledge". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- William Swann's Homepage including many of his works

- International Society for Self and Identity

- Journal of Self and Identity

- Know Thyself - The Value and Limits of Self-Knowledge: The Examined Life is a course offered by Coursera, and is created by a partnership between The University of Edinburgh and Humility & Conviction and Public Life Project, a research project based at the University of Connecticut.