Seil

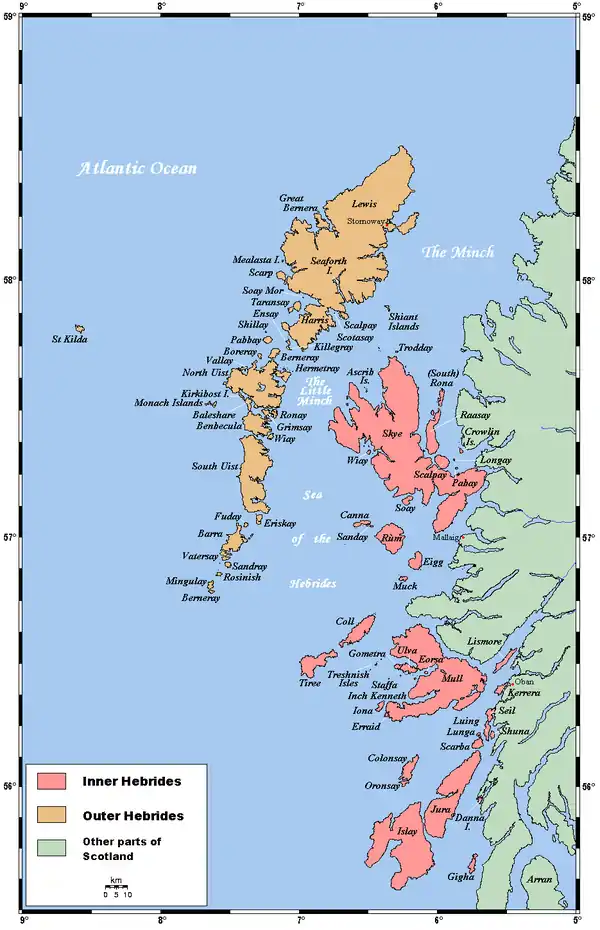

Seil (/ˈsiːl/; Scottish Gaelic: Saoil, Scottish Gaelic pronunciation: [ˈs̪ɯːl]) is one of the Slate Islands, located on the east side of the Firth of Lorn, 7 miles (11 kilometres) southwest of Oban, in Scotland. Seil has been linked to the mainland by bridge since the late 18th century.

| Scottish Gaelic name | Saoil[1] |

|---|---|

Cottages at Ellenabeich under the cliffs of Dùn Mòr | |

| Location | |

Seil Seil shown within Argyll and Bute | |

| OS grid reference | NM742172 |

| Coordinates | 56.30°N 5.62°W |

| Physical geography | |

| Island group | Slate Islands |

| Area | 1,329 ha (5+1⁄8 sq mi) |

| Area rank | 42 [2] |

| Highest elevation | Meall Chaise, 146 m (479 ft) |

| Administration | |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Country | Scotland |

| Council area | Argyll and Bute |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 551[3] |

| Population rank | 21 [2] |

| Population density | 41.4/km2 (107/sq mi)[3] |

| Largest settlement | Balvicar |

| References | [4][5] |

The origins of the island's name are unclear and probably pre-Gaelic. Part of the kingdom of Dalriada in the 7th century, by the sixteenth century Seil seems to have been primarily agricultural in nature. It became part of the estates of the Breadalbane family and in the early 18th century they began to exploit the rich potential of the Neoproterozoic slate beds. The excavations from the island's quarries were exported all over the world during the course of the next two centuries. Today, the economy is largely dependent on agriculture and tourism.

The "dangerous seas"[6] of the Firth of Lorn have claimed many lives and there are several shipwrecks in the vicinity of Seil. Kilbrandon Church has fine examples of stained glass windows and an association with St Brendan.

Etymology

There is some linguistic continuity between the earliest and modern names for many of the larger islands surrounding Scotland. However, the derivations of many of these names are obscure "suggesting that they were coined very early on, some perhaps by the earliest settlers after the Ice Age."[7] Even when names used both in the historic past and the present have some apparent meaning this may indicate a phonetic resemblance to an older name, but one that may be "so old and so linguistically and lexically opaque that we do not have any plausible referents for them."[8][Note 1]

The Ravenna Cosmography, which was compiled by an anonymous cleric in Ravenna around AD 700, mentions various Scottish island names. This document frequently used maps as a source of information and it has been possible to speculate about their modern equivalents based on assumptions about voyages made by early travellers 300–400 years prior to its creation. The island of Saponis mentioned in this list may refer to Seil.[10][Note 2]

Seil is probably a pre-Gaelic name,[1] although a case has been made for a Norse derivation.[12] It has also been argued that Seil could be the location of Hinba, an island associated with St Columba. Reasons include the island's association with St Brendan, its location on an inshore trade route from Antrim to the north and its suitability for a substantial settlement. The Muirbolcmar (great sea bag) referred to in texts about Hinba could refer to the Seil Sound and narrows at Clachan Bridge where the "bag" captures the rapidly flowing water that floods under the bridge. Rae, equating "Hinba" with the Gaelic Inbhir, notes that the adjacent mainland parish of Kilninver means "church of Inbhir" and suggests that the derivation of "Seil" maybe of Scandinavian origin with similarities to the East Frisian place name Zijl or Syl meaning a "seep or passage of water". This, he proposes, could have been a Norse interpretation of Hinba/Inbhir.[13] However, Mac an Tàilleir notes that Kilninver or Cill an Inbhir "appears to mean 'church by the river mouth', and an older form of Cill Fhionnbhair, 'Finbar's church' appears".[14][Note 3]

It has also been suggested that Seil may be the Innisibsolian referred to in the Chronicle of the Kings of Alba, which records a victory of the Scots over a Viking force during the time of Donald II in the 9th century.[15] The name used in the 12th century Book of Leinster is Sóil.[16][Note 4]

The earliest comprehensive written list of Hebridean island names was undertaken by Donald Monro in his Description of the Western Isles of Scotland of 1549 in which Seil is listed. The modern spelling of "Seil" also appears in the 1654 Blaeu Atlas of Scotland.[18]

Geography

Seil is separated from mainland Scotland by the Clachan Sound, which is only about 21.3 metres (70 ft) at its narrowest point.[5][19] To the west lies the sea-lane of the Firth of Lorn. The island of Luing lies across the Cuan Sound to the south and beyond are Lunga and Scarba. Smaller islands surrounding Seil are its companion Slate Islands of Easdale, Torsa, Belnahua and Shuna. Eilean Dubh Mòr is to the south-west with the Garvellachs beyond, with Insh to the north west.[5]

Seil forms part of Nether Lorn, a region of Argyll between Loch Awe and Loch Melfort that includes the offshore islands[20][21] located in the modern council area of Argyll and Bute. The highest point on the island is the summit of Meall Chaise at 146 m (479 ft) above sea level.[5]

Seil is some 7 miles (11 kilometres) miles from Oban, travelling north by road along the B844 and A 816.[5]

Balvicar, in the centre of the island, is the main settlement and has a harbour with commercial fishing boats, the island shop, and a golf club.[22] On the west side of the island lies the former slate-mining village of Ellenabeich. This village, known for its white slate worker's cottages, has attracted an "artist's colony"[4] and has a number of holiday cottages.

There are three other small settlements; Cuan at the southern tip, Oban Seil north of Balvicar and Clachan Seil, which is closest to the Clachan Bridge.[5]

Geology

The larger part of the bedrock of Seil is provided by the Neoproterozoic age Easdale Slate Formation, a pyritic, graphitic pelite belonging to the Easdale Subgroup of the Dalradian Argyll Group. Zones of metamorphosed intrusive igneous rocks occur within the southeast of the island. Andesitic lavas of the Lorn Plateau Lava Formation dominate the west of the island. Seil is cut by numerous NW-SE aligned basalt and microgabbro dykes which form a part of the ‘Mull Swarm’ which is of early Palaeogene age. Raised marine deposits of sand and gravel occur widely around the margins of the island, a legacy of late Quaternary changes in relative sea-level.[23][24][25]

History

The Cenél Loairn kindred controlled what is today known as Lorn in the kingdom of Dalriada. The 7th-century Míniugud senchasa fher nAlban separates the Cenél Loairn into three subsidiary groups, of which the Cenél Salaich may have controlled Nether Lorn.[27][Note 5]

In the mid-16th century Monro wrote of Seil: "Narrest this iyle layes Seill, thre myle of lenthe, ane half myle breidth, leyand from the southwest to the northeast, inhabit and manurit, guid for store and corne, pertaining to the Erl of Ergyle."[28][Note 6]

Ardfad Castle is a ruin in the northwest of Seil. It was the home of the Macdougalls of Ardencaple, but following the failure of King James VII to regain the thrones of England, Ireland and Scotland in the late 17th century the Macdougalls lost much of their lands to the Duke of Argyll.[26] The castle was "a well-built structure of stone and lime, occupying a prominent situation on a crag and tail, not unlike Edinburgh Castle rock. In 1915, it was still fairly well preserved, with the walls standing to some height and two round corner towers".[29] However, by 1971 only the remains of the southwest round tower survived.[29]

Seil then became part of the Netherlorn estates of the Breadalbane family (a branch of Clan Campbell) until the 20th century when their land was sold off as smaller farms and individual houses.[30] In the early 16th century Muriel, daughter of the Thane of Calder, married Sir John Campbell, son of the Earl of Argyll at Inverary and so Clan Campbell of Cawdor was founded. "Many renowned and some infamous" clan members are buried at Kilbrandon churchyard on Seil.[31] From the late 17th century the Dukes of Argyll began to lease land on a competitive basis rather than as a means of strengthening the welfare of their senior clansmen. This resulted in mass evictions from Seil and the surrounding area in 1669, long before the clearances as such.[32]

Slate quarrying

In 1730 Colin Campbell of Carwhin was appointed as the Captain of Ardmaddy and tasked with exploiting the area's natural resources. At this time Easdale slate had been used from as early as the 12th century using seasonal labour from the Ardmaddy estate.[26] In 1745 Campbell created the Easdale Marble and Slate Company in order to place extractions from the area on a more commercial basis.[33] At that point Easdale was producing 1 million slates per annum; when Thomas Pennant visited two years later production had increased by 250% and as further quarries were opened this further increased the company's production to 5 million per annum by 1800.[34]

The little island of Eilean-a-beithich between Seil and Easdale was quarried down to a depth of 80 m (260 ft) and other slate quarries were opened on Luing and at Balvicar. Railway lines were laid to take the rock from the quarries to nearby harbours. Peak production was reached in the 1860s at 9 million slates per annum, with export destinations including England, Nova Scotia, the West Indies, the US, Norway and New Zealand. The 6th Earl of Breadalbane had less interest in the industry than his predecessors although during the time of the 7th Earl a new quarry was opened at Ardencaple.[35] However, disaster struck in 1881. In the early morning of 22 November a severe gale from the south-west wind and an exceptionally high tide flooded the quarries on Easdale and at Eilean-a-beithich "a large rocky buttress which supported a sea wall gave way under the excessive pressure of water".[36][37] Eilean-a-beithich was never re-opened although production did continue at Easdale, Luing and Balvicar. Changes in demand - clay tiles were rapidly replacing slate as the roofing material of choice - led to commercial production ceasing by 1911. Balvicar quarry re-opened from the late 1940s until the early 1960s[38] but slate is no longer mined anywhere in the Slate Islands.

Economy and transport

Today, the island's commerce is largely dependent on agriculture, tourism and lobster fishing.[39] The Ellenabeich Heritage Centre which opened in 2000, is run by the Slate Islands Heritage Trust. Located in a former slate quarry-worker's cottage, the centre has displays about life in the 19th century, slate quarrying and the local flora, fauna and geology.[40][19] Seil has been linked to the Scottish mainland since 1792/3 when the Clachan Bridge was built by engineer Robert Mylne. Also known as the "Bridge Over the Atlantic", the bridge was constructed with a 21.3 m (70 ft) span and has an arch 12.2 m (40 ft) above the sea bed in order to allow small craft of up to 40.6 t (40.0 long tons) to pass under it.[4][19]

Ferries sail from Ellenabeich to Easdale, and from Cuan to Luing across the Cuan Sound. This stretch of water is only 200 m (660 ft) wide but the spring tides race through it at up to 14.4 km/h (7.8 kn).[31] The Easdale ferry uses a chain and cog wheels designed by John Whyte in the mid 19th century.[41]

Religion

Seil is associated with the sixth century saint Brendan of Clonfert who established a monastery on the Garvellachs and at a later date a cell on the site of Kilbrandon Church to which he gave his name.[4][42] The modern church, located between Balvicar and Cuan, has five stained glass windows by Douglas Strachan illustrating scenes from the Sea of Galilee. The central window depicts a ship in distress and "the portrayal in glowing colour of the storm's sweep, the crew's terror, and Christ's self-possession, has a lively drama unique in Highland stained glass".[43]

Folklore and media

The well-known pub Tigh na Truish (Gaelic for 'house of the trousers') at Clachan Seil is said to have obtained its name in the wake of the 1745 Jacobite Rebellion. Supposedly, shore-going islanders swapped their kilts for trousers here after Highland dress was banned.[4][Note 7]

Parts of Ring of Bright Water were filmed on Seil.[4][44]

Notable people

.jpg.webp)

Alexander Beith Free Church Moderator spent about 4 years in this parish. Arthur Murray, 3rd Viscount Elibank and his wife, the actress Faith Celli, purchased property on Seil in the 1930s. They converted a row of derelict cottages into a substantial dwelling and created the 2 ha (5 acres) garden at An Cala, near Ellanabeich.[4][45]

The artist C. John Taylor lived at Ellanabeich for many years until his death in 1998.[46] His painting of the Clachan Bridge "Bridge Over The Atlantic" sold nearly a million copies.[47]

Frances Shand Kydd, the mother of Diana, Princess of Wales lived on the island for many years until her death in 2004.[48]

Shipwrecks

The Firth of Lorn is the seaway used by vessels going to and from Oban and Fort William from points south and the seas around Seil contain the sites of various shipwrecks.

The wooden sailing ship Norval ran aground in fog near the southern tip of Insh on 20 September 1870. The wreckage was still visible in 1995.[49] On 15 August 1900 the 310 t (305 long tons) iron steamship Apollo ran aground on Bono Reef 2.4 km (1.5 mi) south west of Seil. She was carrying a cargo of granite cobble stones from Aberdeen to Newport. The wreck lies in a gully some 10 m (33 ft) down amidst thick kelp.[50] In February 1933 the Clyde puffer Hafton en route from Toboronochy on Luing to Mull sprung a leak and foundered about 14 km (9 mi) into the journey. The crew of five took to a small boat and reached Ellanabeich safely.[51] A wreck of unknown provenance has been recorded .5 km (0.3 mi) east of Rubha Garbh Airde at the northern end of Seil.[49]

Wildlife

In early summer the Clachan Bridge is covered in fairy foxgloves (Erinus alpinus).[4] The narrows that the bridge spans trapped a 23.8 m (78 ft) whale with a 6.4 m (21 ft) long lower jaw in 1835 and no fewer than 192 pilot whales in 1837, the largest of which was 8 m (26 ft) long.[4][19]

According to wildlife experts the entire badger population of the island may have been deliberately exterminated in 2007. Forty of the animals, whose setts were believed to be long established, may have been gassed to death, according to the police. The police also expressed concerns that two golden eagles and one white-tailed sea eagle have been found poisoned near Seil in recent years, involving use of the banned substance carbofuran.[52][53]

Gallery

Clachan Sound from Clachan Bridge, looking north

Clachan Sound from Clachan Bridge, looking north The flooded quarry and village of Ellenabeich with the outline of the former island of Eilean-a-beithich at centre left and Easdale beyond

The flooded quarry and village of Ellenabeich with the outline of the former island of Eilean-a-beithich at centre left and Easdale beyond Slate on the shoreline of Seil

Slate on the shoreline of Seil Flooded slate quarry near Balvicar

Flooded slate quarry near Balvicar The scattered settlement of Oban Seil

The scattered settlement of Oban Seil Balvicar Bay in winter, seen from mainland Scotland, looking towards the heights of Bàrr Mòr

Balvicar Bay in winter, seen from mainland Scotland, looking towards the heights of Bàrr Mòr

Notes

- Broderick is quoting Nicolaisen (1992) p. 2[9]

- Youngson favours Jura as the location of Saponis.[11]

- There are several other contenders for the location of Hinba, including Jura, Colonsay and Canna.

- Haswell-Smith suggests that the name Seil is "probably" from the Gaelic sealg - the hunting island.[17]

- Fraser bases this identification on the linguistic relationships between Salaich, the "flumen Sale" that appears in Adomnán's Vita Columbae and the modern Gaelic name for Seil of Saoil.

- Translation into modern English: "Nearest this isle [of Lunga] lies Seill, three miles long, half a mile broad, oriented southwest to northeast, inhabited and fertilised, good for provisions and corn, [and] owned by the Earl of Argyle."

- Haswell-Smith suggests that the name "may merely mark the site of a tailor's house".[17]

References

Citations

- Mac an Tàilleir (2003), p. 104.

- Area and population ranks: there are c. 300 islands over 20 ha in extent and 93 permanently inhabited islands were listed in the 2011 census.

- National Records of Scotland (15 August 2013). "Appendix 2: Population and households on Scotland's Inhabited Islands" (PDF). Statistical Bulletin: 2011 Census: First Results on Population and Household Estimates for Scotland Release 1C (Part Two) (PDF) (Report). SG/2013/126. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- Haswell-Smith (2004), pp. 76–78.

- Ordnance Survey. OS Maps Online (Map). 1:25,000. Leisure.

- Murray (1966), p. 76.

- Broderick (2013), pp. 20–21.

- Broderick (2013), p. 21.

- Nicolaisen (1992), p. 2.

- Fitzpatrick-Matthews (2013), "Group 34: islands in the Irish Sea and the Western Isles 1".

- Youngson (2001), p. 62.

- Rae (2011), p. 9.

- Rae (2011), pp. 3–11.

- Mac an Tàilleir (2003), p. 72.

- Hudson (1998), p. 9.

- Fraser (2009), p. 246.

- Haswell-Smith (2004), p. 76.

- Blaeu (1654), Lorna.

- Murray (1977), p. 121.

- "Nether Lorn". Gazetteer for Scotland. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- Fraser (2009), p. 245.

- "Seil". Undiscovered Scotland. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- "Onshore Geoindex". British Geological Survey. British Geological Survey. Retrieved 5 February 2020.

- "Kilmartin, Scotland sheet 36, Bedrock and Superficial deposits". BGS large map images. British Geological Survey. Retrieved 5 February 2020.

- "Lismore, Scotland sheet 44(E), Solid Edition". BGS large map images. British Geological Survey. Retrieved 5 February 2020.

- Withall (2013), p. 5.

- Fraser (2009), pp. 245–46.

- Monro (1549), No. 32

- "Seil, Ardfad Castle". Canmore. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- Withall (2013), p. viii.

- Murray (1977), p. 123.

- Duncan (2006), p. 156.

- Withall (2013), p. 6.

- Withall (2013), p. 7.

- Withall (2013), pp. 7–9.

- "Netherlorn and its Neighbourhood:Chapter II - Easdale" Electric Scotland Retrieved 18 March 2012.

- "Slate Islands - The Islands that Roofed the World" Southernhebrides.com. Retrieved 14 November 2009.

- Withall (2013), pp. 9–10.

- Withall (2013), pp. 46–47.

- "Ellenabeich Heritage Centre". Gazetteer for Scotland. Retrieved 25 July 2007.

- Withall (2013), p. 41.

- Murray (1977), p. 122.

- Murray (1977), pp. 122–23.

- "Ring of Bright Water (1969)". Scotland the Movie. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- Withall (2013), p. 46.

- "C John Taylor: Poet/Artist/Composer". Highlandarts.co.uk. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- Murton (2017), p. 29.

- "Obituary: Frances Shand Kydd". BBC. 3 June 2004. Retrieved 29 May 2018.

- Baird (1995), p. 117.

- Baird (1995), pp. 115.

- Baird (1995), pp. 115–16.

- " Police fear island's historic badger population has been exterminated" wildland-network.org.uk reporting Press and Journal article (25 April 2007). Aberdeen. Retrieved 18 February 2008. Archived 3 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- "UK | Scotland | Glasgow and West | Officers hunt for badger baiters". BBC News. 23 April 2007. Retrieved 30 March 2012.

Bibliography

- Baird, Bob (1995), Shipwrecks of the West of Scotland, Glasgow: Nekton Books, ISBN 1897995024

- Broderick, George (2013), "The Journal of Scottish Name Studies", Some Island Names in the Former 'Kingdom of the Isles': a reappraisal, vol. 7

- Blaeu, Joan (1654), "Blaeu Atlas of Scotland (Theatrum Orbis Terrarum Sive Atlas Novus)", National Library of Scotland, retrieved 8 February 2014

- Duncan, P. J. (2006), "The Industries of Argyll: Tradition and Improvement", in Omand, Donald (ed.), The Argyll Book, Edinburgh: Birlinn, ISBN 1-84158-480-0

- Fitzpatrick-Matthews, Keith J (5 August 2013), Britannia in the Ravenna Cosmography: a reassessment, Academia.edu

- Fraser, James E. (2009), The New Edinburgh History of Scotland Vol.1 - From Caledonia To Pictland, Edinburgh University Press, ISBN 978-0-7486-1232-1

- Haswell-Smith, Hamish (2004), The Scottish Islands, Edinburgh: Canongate, ISBN 978-1-84195-454-7

- Hudson, Benjamin T. (October 1998). "The Scottish Chronicle". Scottish Historical Review. 77 (204): 129–161. doi:10.3366/shr.1998.77.2.129.

- Mac an Tàilleir, Iain (2003), Placenames (PDF), Pàrlamaid na h-Alba, retrieved 23 July 2010

- Monro, Sir Donald (1549) Description of the Western Isles of Scotland. William Auld. Edinburgh - 1774 edition.

- Murray, W. H. (1966). The Hebrides. London: Heinemann.

- Murray, W. H. (1977). The Companion Guide to the West Highlands of Scotland. London: Collins. ISBN 0002168138.

- Murton, Paul (2017), The Hebrides, Edinburgh: Birlinn, ISBN 978-1-78027-467-6

- Nicolaisen, W.F.H. (1992), "Arran Place-Names: a fresh look", Northern Studies, 28

- Rae, Robert J. (2011), J Overnell (ed.), "A Voyage in Search of Hinba", Historic Argyll, Lorn Archaeological and Historical Society (16)

- Withall, Mary (2013), Easdale, Benbecula, Luing & Seil: The Islands that Roofed the World, Edinburgh: Luath Press, ISBN 978-1-908373-50-2

- Youngson, Peter (2001), Jura: Island of Deer, Edinburgh: Birlinn, ISBN 1-84158-136-4