Second wind (sleep)

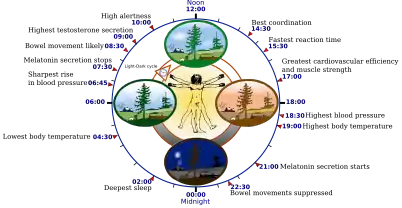

Second wind (or third wind, fourth wind, etc.), a colloquial name for the scientific term wake maintenance zone, is a sleep phenomenon in which a person, after a prolonged period of staying awake, temporarily ceases to feel drowsy, often making it difficult to fall asleep when exhausted.[1][2] They are the result of circadian rhythms cycling into a phase of wakefulness.[3] For example, many people experience the effects of a second wind in the early morning even after an entire night without sleep because it is the time when they would normally wake up.

While most "winds" coincide with the 24-hour cycle, those experiencing extended sleep deprivation over multiple days have been known to experience a "fifth day turning point".

Characteristics

The "second wind" phenomenon may have evolved as a survival mechanism as part of the fight-or-flight response, allowing sleep-deprived individuals briefly to function at a higher level than they would without sleep deprivation.[4]

Performance enhancement

One study presented a series of tasks of increasing difficulty to 16 young adults who had not slept in 35 hours and observed heightened activity in several brain regions using magnetic resonance imaging.[5] Researcher Sean P.A. Drummond commented that the ability to summon a second wind allowed them to "call on cognitive resources they have that they normally don't need to use to do a certain task". (He also noted that their performance, though an improvement considering their state of sleep deprivation, were below what it would be had they slept.)

Another study found significant improvement in the performance of 31 adults on various neurobehavioral tests after the onset of the wake maintenance zone as compared to their performance just three hours prior, despite the fact that the subjects had been awake longer.[6] The improvement as test subjects caught another wind was even more pronounced on the second day of extended wakefulness. A later study reproduced similar results.[7]

Duration

The wake maintenance zone generally lasts 2 to 3 hours, during which one is less inclined to fall asleep.[6] While potentially useful for completing urgent tasks, it may have a potentially unwanted side-effect of keeping one awake for several hours after the task has been completed. The hypervigilance and stimulation brought on by a second wind can cause fatigue, which, in the case of infants, can be literally painful.[4] Thus, an infant may begin crying when sleep habits are disrupted.

"Fifth day turning point"

Multiple studies have observed that individuals subjected to total sleep deprivation for extended periods spanning multiple days may feel "helplessly sleepy" up until the fifth day, upon which all observed individuals would feel what may be described as a second wind.[8] This particular form of the experience has been dubbed the "fifth day turning point" (Pasnau et al. 1968).

Causes

There are multiple possible ways by which a person may experience a second wind, depending on the time of day. A second wind at around 6:00–8:00 a.m. may be explained by cortisol, a light-triggered hormone, peaking at that time. Cortisol helps facilitate adrenaline's role in glycogenolysis and, therefore, in glucose release.[9] This may help to maintain one's wakefulness. As late afternoon transitions into evening, changes in light levels can stimulate the suprachiasmatic nucleus in the brain to promote an arousal signal.[10] At about 10:30 p.m. (depending on factors including the season and the condition of the individual), melatonin—the hormone responsible for preparing the body for sleep—peaks; a second wind may occur at this time if a person resists sleeping or fails to fall asleep before the peak.[9] Such second winds could aggravate sleep debt.

In 2018, the second wind phenomenon, or "forbidden sleep zone of the wake maintenance zone", in scientific terms,[11] was found to be caused by the buildup of dopamine in proportion to the time spent awake, as a paradoxical counterbalance to adenosine, the hormone of sleep pressure.[12]

Although there is one zone of minimal sleep tendency, which is often termed the "wake maintenance zone" "approximately one to three hours before habitual bedtime",[13] there are several other zones of lower sleep tendency; hence, these zones should be collectively termed "wake maintenance zones" in the plural, or the more colloquial "sleep gates".[7][11]

Interactions with medications

When hypnotic medications are administered too early in the evening, such medications may reach peak their levels in the blood during the wake maintenance zone. Not only could this negate the soporific effectiveness of the medication, it may also cause users of the drug to experience disinhibition, hallucinations, or other dissociative phenomena, should they remain awake.[2]

See also

References

- "Nickelodeon Parents".

- Stephen H. Sheldon; Meir H. Kryger; Richard Ferber; David Gozal (2005). "Principles and Practice of Pediatric Sleep Medicine".

- "PsychEd Up, Vol. 2, Issue 2" (PDF). p. 6. Retrieved 16 May 2013.

- Weissbluth, Marc (1999). Healthy Sleep Habits, Happy Child. ISBN 9780449004029.

- Marill, Michele Cohen. "Surviving the Day After an All-Nighter". WebMD.

- Julia A. Shekleton; Shantha M. W. Rajaratnam; Joshua J. Gooley; Eliza Van Reen; Charles A. Czeisler & Steven W. Lockley. (Apr 15, 2013). "Improved Neurobehavioral Performance during the Wake Maintenance Zone". Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 09 (4): 353–362. doi:10.5664/jcsm.2588. PMC 3601314. PMID 23585751.

- Zeeuw, J; Wisniewski, S; Papakonstantinou, A; Bes, F; Wahnschaffe, A; Zaleska, M; Kunz, D; Münch, M (20 July 2018). "The alerting effect of the wake maintenance zone during 40 hours of sleep deprivation". Scientific Reports. 8 (1): 11012. Bibcode:2018NatSR...811012Z. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-29380-z. PMC 6054682. PMID 30030487.

- Neilsen, Tore A, Marie Dupont, and Jacque Montplaisir. "A 20-h recovery sleep after prolonged sleep restriction: some effects of competing in a world record-setting cinemarathon" (PDF).

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Brunshaw, Jacquelinee (July 31, 2012). "Paying the sandman: Bad night patterns, chronic sleep debt and risks to your health". National Post.

- Lieberman III, Joseph A. & David N. Neubauer. "Normal Sleep and Wakefulness" (PDF).

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Lavie, P (May 1986). "Ultrashort sleep-waking schedule. III. 'Gates' and 'forbidden zones' for sleep". Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology. 63 (5): 414–25. doi:10.1016/0013-4694(86)90123-9. PMID 2420557.

- Volkow, Nora D.; Wang, Gene-Jack; Telang, Frank; Fowler, Joanna S.; Logan, Jean; Wong, Christopher; Ma, Jim; Pradhan, Kith; Tomasi, Dardo; Thanos, Peter K.; Ferré, Sergi; Jayne, Millard (20 August 2008). "Sleep Deprivation Decreases Binding of [11C]Raclopride to Dopamine D2/D3 Receptors in the Human Brain". Journal of Neuroscience. 28 (34): 8454–8461. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1443-08.2008. PMC 2710773. PMID 18716203.

- Strogatz, SH; Kronauer, RE; Czeisler, CA (July 1987). "Circadian pacemaker interferes with sleep onset at specific times each day: role in insomnia". The American Journal of Physiology. 253 (1 Pt 2): R172-8. doi:10.1152/ajpregu.1987.253.1.R172. PMID 3605382.