Sardanapalus (play)

Sardanapalus (1821) is a historical tragedy in blank verse by Lord Byron, set in ancient Nineveh and recounting the fall of the Assyrian monarchy and its supposed last king. It draws its story mainly from the Historical Library of Diodorus Siculus and from William Mitford's History of Greece. Byron wrote the play during his stay in Ravenna, and dedicated it to Goethe. It has had an extensive influence on European culture, inspiring a painting by Delacroix and musical works by Berlioz, Liszt and Ravel, among others.

| Sardanapalus | |

|---|---|

First edition title page | |

| Written by | Lord Byron |

| Characters |

|

| Mute | Women of the harem, guards, attendants, Chaldean priests, Medes etc. |

| Date premiered | 10 April 1834 |

| Place premiered | Theatre Royal, Drury Lane |

| Original language | English |

| Subject | The fall of the Assyrian monarchy |

| Genre | Historical tragedy, blank verse tragedy, closet drama |

| Setting | The Royal Palace at Nineveh |

Synopsis

Act 1

In a soliloquy Salemenes deplores the life of slothful luxury led by his brother-in-law Sardanapalus, king of Assyria. The king enters, and Salemenes reproaches him with his lack of ambition for military glory and his unfaithfulness to his queen, Salemenes' sister. He warns him of possible rebellion by treacherous courtiers. Sardanapalus answers by extolling the virtues of mild and merciful rule and condemning bloodshed, but is finally persuaded to give Salemenes his signet so that he can arrest the rebel leaders. Salemenes leaves, and Sardanapalus reflects,

Till now, no drop from an Assyrian vein

Hath flow'd for me, nor hath the smallest coin

Of Nineveh's vast treasures e'er been lavish'd

On objects which could cost her sons a tear:

If then they hate me, 'tis because I hate not:

If they rebel, 'tis because I oppress not.[1]

The Greek slave-girl Myrrha, Sardanapalus' favourite, enters; when Sardanapalus proposes to spend the evening banqueting by the Euphrates she persuades him not to go, fearing some danger there.

Act 2

The Chaldean astrologer Beleses predicts the downfall of Sardanapalus, then meets the satrap Arbaces and plots the king's murder with him. Salemenes enters and tries forcibly to arrest both men, but Sardanapalus arrives unexpectedly and, not wanting to believe that Beleses and Arbaces could be traitors, breaks up the struggle. Salemenes and the king leave, and Arbaces, shamed by the king's clemency, momentarily abandons his regicidal intentions. A messenger arrives from the king, telling the two satraps to return to their respective provinces without their troops. Beleses believes this to be the prelude to a death sentence. Arbaces agrees:

Why, what other

Interpretation should it bear? it is

The very policy of orient monarchs –

Pardon and poison – favours and a sword –

A distant voyage, and an eternal sleep […]

How many satraps have I seen set out

In his sire's day for mighty vice-royalties,

Whose tombs are on their path! I know not how,

But they all sicken'd by the way, it was

So long and heavy.[2]

They leave, resolving to defend themselves by rebellion. Sardanapalus and Salemenes enter, and it becomes clear that Sardanapalus is now persuaded of the plotters' guilt, but still does not repent of sparing them. Myrrha joins the king and urges him to execute Beleses and Arbaces, but he, as ever, rejects the shedding of blood.

Act 3

The king is banqueting when news reaches him that the two satraps have refused to leave the city and have led their troops in rebellion. Sardanapalus arms himself and, after admiring his newly martial appearance in a mirror, goes to join Salemenes and his soldiers, now the only ones loyal to him. Myrrha, left behind, hears reports that a battle is in progress, and is going badly for the king. Sardanapalus and Salemenes return, closely followed by the rebels, but they beat the attack off and congratulate themselves on a victory. Sardanapalus admits to being slightly wounded.

Act 4

Sardanapalus awakes from a troubled sleep and tells Myrrha that he has had a nightmare of banqueting with his dead ancestors, the kings of Assyria. Salemenes now brings in his sister, Zarina, Sardanapalus' long-estranged wife, and these two are left alone together. Zarina proposes to take their children abroad for safety, and makes it clear that she still loves him. As they talk the king gradually becomes reconciled to his wife. She faints at the prospect of parting, and is carried out. Myrrha enters, and the king, initially embarrassed by her presence, falls under her spell again.

I thought to have made mine inoffensive rule

An era of sweet peace 'midst bloody annals,

A green spot amidst desert centuries,

On which the future would turn back and smile,

And cultivate, or sigh when it could not

Recall Sardanapalus' golden reign.

I thought to have made my realm a paradise,

And every moon an epoch of new pleasures.

I took the rabble's shouts for love – the breath

Of friends for truth – the lips of woman for

My only guerdon – so they are, my Myrrha: [He kisses her]

Kiss me. Now let them take my realm and life!

They shall have both, but never thee![3]

Salemenes enters, and the king orders an immediate attack on the rebels.

Act 5

As Myrrha waits in the palace, conversing with one of the courtiers, a wounded Salemenes is brought in, a javelin protruding from his side. He draws out the javelin and dies of the consequent blood-loss. Sardanapalus, who has also returned, desponds about his prospects in the unfolding battle. Then he is told that the Euphrates, being in violent flood, has torn down part of the city wall, leaving no defence against the enemy except the river itself, which must presently recede. A herald arrives and offers Arbaces' terms: Sardanapalus' life if he will surrender. The king refuses these terms, but asks for a truce of one hour. He uses this interval to have a pyre erected under his throne, and bids his last faithful officer save himself by fleeing. Sardanapalus and Myrrha say their last farewells to each other and to the world, then he climbs to the top of the pyre, and she throws a torch into it and joins him.

Composition and publication

Sardanapalus was written while the author was living in Ravenna with his lover, Teresa, Countess Guiccioli, and is sometimes seen as portraying the Countess and Byron himself in the characters of Myrrha and Sardanapalus.[4] At the beginning of 1821 he turned to this story, which he had known since he was twelve years old, and began researching the details. On 14 January he wrote the first lines, and on 14 February completed the first act.[5] On 31 May he was able to send the completed play to his usual publisher, John Murray, with the comment that it was "expressly written not for the theatre".[6] Setting out his principle that drama should be based on hard fact he commented on Sardanapalus and The Two Foscari that

My object has been to dramatize like the Greeks (a modest phrase!) striking passages of history, as they did of history & mythology. You will find all this very unlike Shakespeare; and so much the better in one sense, for I look upon him to be the worst of models, though the most extraordinary of writers.[7]

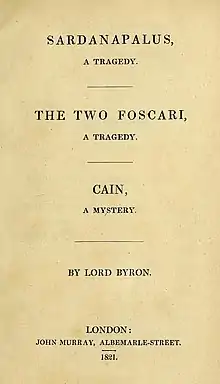

Murray published Sardanapalus on 19 December 1821 in the same volume with The Two Foscari and Cain. Byron's intended dedication of the play to Goethe was omitted, but it did finally appear in the edition of 1829.[8]

Sources

In a prefatory note to Sardanapalus Byron acknowledged the Historical Library of Diodorus Siculus (a work he had known since he was 12) as the major source of the plot, while exercising his right to alter the facts of history so as to maintain the dramatic unities, but it is known that he also used William Mitford's History of Greece. The passage in which Sardanapalus calls for a mirror to admire his own appearance in armour was, on Byron's own evidence, suggested by Juvenal Satires, Bk. 2, lines 99–103.[9] The character of Myrrha does not appear in any historical account of Sardanapalus, but the critic Ernest Hartley Coleridge noted a resemblance to Aspasia in Plutarch's life of Artaxerxes, and claimed that her name was probably inspired by Alfieri's tragedy Mirra, which Byron had seen in Bologna in 1819. He also suggested that the style of Sardanapalus was influenced by Seneca the Younger, whose tragedies Byron certainly mentions browsing through just before he began work on it.[10]

Performance history

Byron intended his play as a closet piece, writing that it was "expressly written not for the theatre".[11] His wishes were respected during his own lifetime, but in January 1834 a French translation, or rather imitation, was played in Brussels.[12] Later in 1834 the original tragedy was performed at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane with Macready taking the title role. It was said that Byron had wanted Charlotte Mardyn to play the role of Myrrha as she had been Byron's lover. Macready was not keen to cast her[13] and Ellen Tree played Myrrha. Almost twenty years later Charles Kean played Sardanapalus at the Princess's Theatre, London, with Ellen Tree (by then Mrs. Ellen Kean) again appearing as Myrrha. In 1877 the actor-manager Charles Calvert played Sardanapalus in his own adaptation of the play, and this adaptation was also staged at Booth's Theatre in New York.[12]

Legacy

Byron's Sardanapalus was one of the literary sources–others include Diodorus Siculus and the Roman historian Quintus Curtius Rufus–of Eugène Delacroix' major historical painting La Mort de Sardanapale, completed between November 1827 and January 1828. It depicts the Assyrian king preparing for death surrounded by concubines, rather than in the company of Myrrha alone as Byron would have it.[14] Thereafter the death of Sardanapalus became a favourite subject for composers, especially in France. In 1830 competitors for the Paris Conservatoire's Prix de Rome were given J.-F. Gail's La Mort de Sardanapale, a text based on Byron's play and Delacroix' painting, to set as a cantata.[15] Hector Berlioz, in his fourth attempt on the prize, took the first prize.[16]

In the mid-1840s Franz Liszt conceived the idea of writing an Italian opera based on Sardanapalus, and procured an Italian libretto to that purpose, but he did not actually begin writing until 1849. He completed the music for Act 1 of his Sardanapalo in an annotated short score, but seems to have abandoned the project during 1852.[17] In 2019, the first critical and performance editions of Liszt's music (110 pages) were published, edited by the British musicologist David Trippett; a world premiere recording was released by the Staatskapelle Weimar to critical acclaim.[18][19] Liszt's original manuscript survives in Weimar's Goethe- und Schiller-Museum.[20][21] Several other Sardanapale operas based on Byron's play were completed by the composers Victorin de Joncières, Alphonse Duvernoy, Giulio Alary, and the Baronne de Maistre, and one was projected by the young Ildebrando Pizzetti.[12][22][23][24] In 1901 the Prix de Rome committee selected Fernand Beissier's Myrrha, a pale imitation of Sardanapalus, as the text to be set. The prize was won by André Caplet on this occasion, but Maurice Ravel's entry is the only one of the 1901 entries to remain in the repertoire.[25]

Footnotes

- Act 1, sc. 2, line 408.

- Act 2, sc. 1, line 428

- Act 4, sc. 1, line 511.

- Ward, A. W.; Waller, A. R. Waller, eds. (1915). The Cambridge History of English Literature, Vol. 12. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 49. Retrieved 8 August 2013.

- Wolfson, Susan J. (2006). Borderlines: The Shiftings of Gender in British Romanticism. Stanford: Stanford University Press. pp. 140–143. ISBN 978-0-8047-5297-8. Retrieved 8 August 2013.

- Marchand 1978, pp. 128–129.

- Goode, Clement Tyson (1964) [1923]. Byron as Critic. New York: Haskell House. p. 110. Retrieved 8 August 2013.

- Marchand 1978, p. 198.

- Marchand 1978, pp. 26, 128, 129.

- Coleridge 1905, pp. 3, 5.

- Mathur, Om Prakash (1978). The Closet Drama of the Romantic Revival. Salzburg: Institut für englische Sprache und Literatur, Universität Salzburg. p. 155. ISBN 9780773401624. Retrieved 9 August 2013.

- Coleridge 1905, p. 2.

- Kate Mitchell (3 December 2012). Reading Historical Fiction: The Revenant and Remembered Past. Springer. pp. 120–. ISBN 978-1-137-29154-7.

- "Inspiration for the Death of Sardanapalus". The Open University. Retrieved 9 August 2013.

- Holoman, D. Kern (1989). Berlioz: A Musical Biography of the Creative Genius of the Romantic Era. Harvard University Press: Cambridge, Mass. p. 63. ISBN 0-674-06778-9. Retrieved 10 August 2013.

- Bloom, Peter (1981). "Berlioz and the Prix de Rome of 1830" (PDF). Journal of the American Musicological Society. 34 (2): 279–280. doi:10.1525/jams.1981.34.2.03a00040. Retrieved 9 August 2013.

- David Trippett, 'An Uncrossable Rubicon', Journal of the Royal Music Association 143 (2018), 361-432 https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/02690403.2018.1507120

- Connolly, Kate (17 August 2018). "Liszt's lost opera: 'beautiful' work finally brought to life after 170 years". Theguardian.com.

- "Music to the ears: The story of Liszt's lost opera". 18 February 2019.

- Trippett (2018) 389

- Searle, Humphrey (1954). The Music of Liszt. London: Williams & Norgate. p. 89.

- Montfort, Eugène (1925). Vingt-cinq ans de littérature française, tome 1. Paris: Librairie de France. p. 198.

- Arnaoutovitch, Alexandre (1927). Henry Becque, tome 2. Paris: Presses universitaires de France. p. 230.

- Gatti, Guido M. (1954). "Pizzetti, Ildebrando". In Blom, Eric (ed.). Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians. Volume 6 (5th ed.). London: Macmillan. p. 807.

- Orenstein, Arbie (1991). Ravel: Man and Musician. London: Constable. pp. 34–36. ISBN 0-486-26633-8. Retrieved 10 August 2013.

References

- Coleridge, Ernest Hartley, ed. (1924). The Works of Lord Byron: Poetry, Vol. 5. London: John Murray. Retrieved 17 July 2013.

- Marchand, Leslie A., ed. (1978). Born for Opposition. Byron's Letters and Journals, Vol. 8. London: John Murray. ISBN 0-7195-3451-8.

- Trippett, David, "An Uncrossable Rubicon: Liszt's Sardanapalo Revisited," Journal of the Royal Music Association 143 (2018), 361-432.

.jpg.webp)