San Mateo Creek (San Francisco Bay Area)

San Mateo Creek (Spanish for: St. Matthew Creek) is a perennial stream whose watershed includes Crystal Springs Reservoir, for which it is the only natural outlet after passing Crystal Springs Dam.

| San Mateo Creek Arroyo De San Mateo, Arroyo De San Matheo[1] | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) San Mateo Creek just downstream of Gateway Park, where the creek passes under the intersection of Third and Humboldt (Aug 2018) | |

Location of the mouth of San Mateo Creek in California | |

| Etymology | Saint Matthew |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| State | California |

| Region | San Francisco Peninsula |

| County | San Mateo County |

| Cities | Hillsborough, San Mateo |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | |

| • coordinates | 37°35′35″N 122°26′59″W |

| • elevation | 1,000 ft (300 m) |

| Mouth | |

• coordinates | 37°34′30″N 122°18′17″W |

• elevation | 7 ft (2.1 m) |

| Length | 12 mi (19 km) |

| Discharge | |

| • location | San Francisco Bay |

| Basin features | |

| Tributaries | |

| • left | San Andreas Creek |

| • right | Laguna Creek, Polhemus Creek |

History

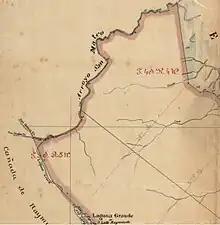

After discovering San Francisco Bay from Sweeney Ridge on November 4, 1769, the Portolà expedition descended what Portolà called the Cañada de San Francisco, now San Andreas Creek (or possibly San Mateo Creek). "Laguna Grande" is where the party camped (now covered by the Upper Crystal Springs Reservoir). The Laguna Grande place name is also shown on the 1840s diseño del Rancho Cañada de Raymundo[2] and an 1856 plat.[3] The campsite is marked by California Historical Marker No. 94 "Portola Expedition Camp".[4] They camped here a second time on November 12, on their return trip.[5]

Padre Palóu, on an expedition from Mission San Carlos Borromeo (Carmel) to explore the western side of San Francisco Bay led by Captain Fernando Rivera, renamed Portola's Cañada de San Francisco to Cañada de San Andrés on November 30, 1774, it being the feast day of St. Andrew.[6] Palou's name was later applied to the San Andreas fault (misspelled) when the fault was discovered to be the creator of the valley.

In 1776, the expedition led by Captain Juan Bautista de Anza, rather than stay on the coast as Portola had done, followed an inland route from Monterey, California established by Pedro Fages in 1770. De Anza descended the Santa Clara Valley to San Francisco Bay and followed its western shoreline up the peninsula to San Francisco. The de Anza party selected the sites for Mission San Francisco de Asís (Mission Dolores) and the Presidio of San Francisco. De Anza picked up Portola's trail at San Francisquito Creek, following the Cañada de San Andrés north from there. On the return to Monterey, the party camped on the banks of San Mateo Creek on March 29, 1776.

In de Anza's diary on March 29, 1776, he wrote: "Night having fallen, at a quarter past six I went down to the arroyo of San Andreas and to another, that of San Matheo, where it descends to empty into the estuary. There I found in our camp nearly all the men of the village, very friendly, content, and joyful, putting themselves out to serve us in every way, a circumstance which I have noted in all the natives seen from the 26th up to now, but one which I had not experienced theretofore since leaving the people of the Colorado River."[7]

It is likely that de Anza had met the Ssalson tribe of Ohlone people. The records of the Mission San Francisco de Asís indicate that the Ssalson had three villages along San Mateo Creek and San Andreas Creek named Altagmu, Aleitac, and Uturbe. By 1794, the members of the tribe had moved to the mission.[8]

Shortly thereafter, the rest of the de Anza party – families, soldiers, and priests on their way to help establish the presidio and mission – also camped here for three days, June 24–27, 1776. A plaque labelled "California State Historical Landmark No. 47 Anza Expedition Camp" is located at Arroyo Court, one block west on West 3rd Avenue, San Mateo.[9]

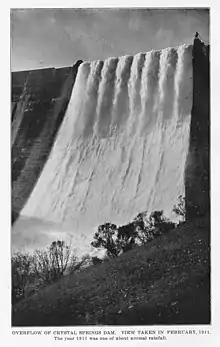

Watershed

San Mateo Creek's source elevation is at almost 1,000 feet on Sweeney Ridge from which it flows southeasterly (in a valley east of Cahill Ridge and west of Sawyer Ridge) for 11.2 km (7 mi) before entering the northwest arm of Lower Crystal Springs Reservoir. The northeast arm of Lower Crystal Springs Reservoir is formed by San Mateo Creek's tributary, San Andreas Creek which descends to the Reservoir southeast along the San Andreas Rift. Another tributary, Laguna Creek, flows northwards from Woodside with its source on Edgewood County Park and Natural Preserve, and historically fed Laguna Grande and then joined San Mateo Creek just upstream from Crystal Springs Canyon, where San Mateo Creek turned east to flow through the canyon. Laguna Grande was submerged when an earthen dam (this was the first Crystal Springs Dam) was constructed in 1877, forming Upper Crystal Springs Reservoir.[10][11] The old earthen dam became a causeway between Upper and Lower Crystal Springs Reservoirs when the latter was formed by Herman Schussler's concrete Crystal Springs Dam, which dammed up San Mateo Creek in 1888 to form the lower reservoir.[12] The causeway is now crossed by Highway 92. In addition to San Mateo Creek and its San Andreas Creek and Laguna Creek tributaries, the waters of Crystal Springs Reservoir consist of runoff from the eastern slopes of the Montara block of the Santa Cruz Mountains and imported Hetch Hetchy Aqueduct water deriving from the Sierra Nevada. The two Crystal Springs lakes and San Andreas Lake used to be known as Spring Valley Lakes for the Spring Valley Water Company which owned them. Lower Crystal Springs Reservoir now covers the town of Crystal Springs which grew up around a resort of the same name.[6]

From the Crystal Springs Dam San Mateo Creek flows generally northeast 8 km (5 mi) through San Mateo where it is partly intermittent and altered, to San Francisco Bay about 1.1 km (0.7 mi) west of the mouth of Seal Slough.[1] This watercourse lies entirely within San Mateo County and flows generally eastward to discharge into San Francisco Bay.

Ecology

.jpg.webp)

San Mateo Creek once hosted coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch) as evidenced by specimens collected by Professor Alexander Agassiz of Harvard University in the 1850s and 1860s.[13][14] He also collected steelhead trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) from the creek.[15] Historical records indicate that Chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) occurred in at least two San Francisco Bay Area watersheds, San Mateo Creek in San Mateo County and San Leandro Creek in Alameda County.[15]

Fog drip may play a key role in the precipitation in the upper watershed. On Cahill Ridge, just west of San Mateo Creek and east of Pilarcitos Creek, at an altitude of 1,000 feet, Oberlander measured fog drip beneath tanoak (Lithocarpus densiflorus), coast redwood and three Douglas fir trees, the latter 125 feet tall. He found that the trees most exposed produced the most precipitation and in five weeks of measurement (July 20-August 28, 1951) fog drip below the tanoak produced 59 inches of precipitation, more than the total annual precipitation on nearby grasslands and chaparral. The Douglas fir produced 7-17 inches of fog drip and appeared to provide unique conditions supporting the orchids giant helleborine (Epipactis gigantea) and phantom orchid (Cephalanthera austiniae), since these plants were found exclusively in these moist ridge tops.[16]

The upper reach of the lower watershed of San Mateo Creek below Crystal Springs Dam consists of open space and sparsely developed residential areas of the cities of Hillsborough and San Mateo, California. This upper reach consists of closed canopy California oak woodland and serpentine grassland. The creek roughly parallels Crystal Springs Road through this section. Due to the unusual microclimate and presence of abundant serpentine there are an unusual number of rare plants in the upper catchment basin.[17]

The middle reach consists of increasingly dense single family and multifamily residential land use along with some adjacent school, park and commercial uses. In the lower phase of the middle reach, San Mateo Creek is fully culverted through downtown San Mateo. In the lowest reach San Mateo Creek becomes tidal and discharges to San Francisco Bay between Ryder Park and Seal Point Park.

The creek mouth area contains slough and wetland habitats including mudflats that are known habitat of the endangered California clapper rail. San Mateo Creek was federally designated in 2002 as a section 303 impaired watershed for the substance diazinon;[18] however, diazinon has been banned for golf course use by the U.S. Government. There is one golf course that provides surface runoff to San Mateo Creek in the city of San Mateo, and Crystal Springs Golf Course that drains to the Crystal Springs Reservoir.

Watercourse gallery

Crystal Springs Dam, 1911

Crystal Springs Dam, 1911 Roadways added on top of dam

Roadways added on top of dam Dam view from under Interstate 280

Dam view from under Interstate 280 Below the dam

Below the dam.jpg.webp) Near California Historical Landmark no. 47

Near California Historical Landmark no. 47.jpg.webp) At Gateway Park

At Gateway Park.jpg.webp) Above J. Hart Clinton Drive bridge

Above J. Hart Clinton Drive bridge.jpg.webp) Pedestrian bridge at Ryder Park

Pedestrian bridge at Ryder Park.jpg.webp) Mouth at Ryder Park

Mouth at Ryder Park

See also

References

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: San Mateo Creek

- "Diseño del Rancho Cañada de Raymundo". Calisphere, University of California. Retrieved 2011-10-09.

- Erwin Gustav Gudde (1974). California Place Names. University of California Press. p. C-261. Retrieved 2011-10-09.

- "California Historical Landmarks". California State Parks Office of Historic Preservation. Retrieved 2011-10-09.

- "California Historical Landmarks". California Office of Historic Preservation. Retrieved 2010-07-13.

- David L. Durham (1998). California's geographic names: a gazetteer of historic and modern names of the state. Quill Driver Books. p. 694. ISBN 978-1-884995-14-9. Retrieved 2010-07-13.

- de Anza; Juan Bautista (1776). Diary of Juan Bautista de Anza October 23, 1775 – June 1, 1776. University of Oregon Web de Anza pages. Retrieved 2010-07-13.

- Milliken, Randall. A Time of Little Choice: The Disintegration of Tribal Culture in the San Francisco Bay Area 1769-1810 Menlo Park, CA: Ballena Press Publication, 1995. ISBN 0-87919-132-5

- "California Historical Landmarks". California Office of Historic Preservation. Retrieved 2010-07-13.

- David L. Durham (1998). California's geographic names: a gazetteer of historic and modern names of the state. Quill Driver Books. p. 658. ISBN 978-1-884995-14-9. Retrieved 2010-07-13.

- Alan Hynding (1982). From Frontier to Suburb, The Story of the San Francisco Peninsula. Belmont, California: Star Publishing Company. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-89863-056-5.

- Ferol Egan (1998). Last bonanza kings: the Bourns of San Francisco. University of Nevada Press. p. 167. ISBN 978-0-87417-319-2. Retrieved 2011-10-11.

- Robert A. Leidy; Gordon Becker; Brett N. Harvey (2005). "Historical Status of Coho Salmon in Streams of the Urbanized San Francisco Estuary, California" (PDF). California Fish and Game: 219–254. Retrieved 2011-09-19.

- "Oncorhynchus kisutch". Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology. Retrieved 2010-10-28.

- Robert A. Leidy (April 2007). Ecology, Assemblage Structure, Distribution, and Status of Fishes in Streams Tributary to the San Francisco Estuary, California (Report). San Francisco Estuary Institute. Retrieved 2010-10-21.

- G. T. Oberlander (October 1956). "Summer Fog Precipitation on the San Francisco Peninsula". Ecology. 37 (4): 851–852. doi:10.2307/1933081. JSTOR 1933081.

- Environmental Impact Report for the Hillsborough Highlands Estates, Earth Metrics Report 7803 (Report). California State Clearinghouse. November 1989.

- Federal impairment profile for San Mateo Creek (PDF) (Report). June 2006. Retrieved 2010-07-11.

.jpg.webp)