SMS Nassau

SMS Nassau[lower-alpha 1] was the first dreadnought battleship built for the Imperial German Navy, a response to the launching of the British battleship HMS Dreadnought.[2] Nassau was laid down on 22 July 1907 at the Kaiserliche Werft in Wilhelmshaven, and launched less than a year later on 7 March 1908, approximately 25 months after Dreadnought. She was the lead ship of her class of four battleships, which included Posen, Rheinland, and Westfalen.

Nassau, very early in her career | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Nassau |

| Namesake | Duchy of Nassau part of the Prussian province of Hesse Nassau[1] |

| Builder | Kaiserliche Werft, Wilhelmshaven |

| Laid down | 22 July 1907 |

| Launched | 7 March 1908 |

| Commissioned | 1 October 1909 |

| Fate | Ceded to Japan as war prize, sold for scrap in 1920 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Nassau-class battleship |

| Displacement | |

| Length | 146.1 m (479 ft 4 in) |

| Beam | 26.9 m (88 ft 3 in) |

| Draft | 8.9 m (29 ft 2 in) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed | 20 knots (37 km/h; 23 mph) |

| Range | At 12 knots (22 km/h; 14 mph): 8,300 nmi (15,400 km; 9,600 mi) |

| Complement |

|

| Armament |

|

| Armor |

|

Nassau saw service in the North Sea at the beginning of World War I, in II Division of I Battle Squadron of the German High Seas Fleet. In August 1915, she entered the Baltic Sea and participated in the Battle of the Gulf of Riga, where she engaged the Russian battleship Slava. Following her return to the North Sea, Nassau and her sister ships took part in the Battle of Jutland on 31 May – 1 June 1916. During the battle, Nassau collided with the British destroyer HMS Spitfire. Nassau suffered a total of 11 killed and 16 injured during the engagement.

After World War I, the bulk of the High Seas Fleet was interned in Scapa Flow. As they were the oldest German dreadnoughts, the Nassau-class ships were for the time permitted to remain in German ports. After the German fleet was scuttled, Nassau and her three sisters were surrendered to the victorious Allied powers as replacements for the sunken ships. Nassau was ceded to Japan in April 1920. With no use for the ship, Japan sold her to a British wrecking firm which then scrapped her in Dordrecht, Netherlands.

Description

Design work on the Nassau class began in late 1903 in the context of the Anglo-German naval arms race; at the time, battleships of foreign navies had begun to carry increasingly heavy secondary batteries, including Italian and American ships with 20.3 cm (8 in) guns and British ships with 23.4 cm (9.2 in) guns, outclassing the previous German battleships of the Deutschland class with their 17 cm (6.7 in) secondaries. German designers initially considered ships equipped with 21 cm (8.3 in) secondary guns, but erroneous reports in early 1904 that the British Lord Nelson-class battleships would be equipped with a secondary battery of 25.4 cm (10 in) guns prompted them to consider an even more powerful ship armed with an all-big-gun armament consisting of eight 28 cm (11 in) guns. Over the next two years, the design was refined into a larger vessel with twelve of the guns, by which time Britain had launched the all-big-gun battleship HMS Dreadnought.[3]

Nassau was 146.1 m (479 ft 4 in) long, 26.9 m (88 ft 3 in) wide, and had a draft of 8.9 m (29 ft 2 in). She displaced 18,873 t (18,575 long tons) with a normal load, and 20,535 t (20,211 long tons) fully laden. The ship had a crew of 40 officers and 968 enlisted men. Nassau retained three-shafted triple expansion engines with twelve coal-fired water-tube boilers instead of more advanced turbine engines. Her propulsion system was rated at 21,699 ihp (16,181 kW) and provided a top speed of 20 knots (37 km/h; 23 mph). She had a cruising radius of 8,300 nautical miles (15,400 km; 9,600 mi) at a speed of 12 knots (22 km/h; 14 mph).[4] This type of machinery was chosen at the request of both Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz and the Navy's construction department; the latter stated in 1905 that the "use of turbines in heavy warships does not recommend itself."[5] This decision was based solely on cost: at the time, Parsons held a monopoly on steam turbines and required a 1 million gold mark royalty fee for every turbine engine made. German firms were not ready to begin production of turbines on a large scale until 1910.[6]

Nassau carried a main battery of twelve 28 cm (11 in) SK L/45[lower-alpha 2] guns in an unusual hexagonal configuration. Her secondary armament consisted of twelve 15 cm (6 in) SK L/45 guns and sixteen 8.8 cm (3 in) SK L/45 guns, all of which were mounted in casemates.[4] The ship was also armed with six 45 cm (17.7 in) submerged torpedo tubes. One tube was mounted in the bow, another in the stern, and two on each broadside, on either ends of the torpedo bulkhead.[8] The ship's belt armor was 270 mm (11 in)[9] thick in the central citadel, and the armored deck was 80 mm (3 in) thick. The main battery turrets had 280 mm (11 in) thick sides, and the conning tower was protected with 400 mm (16 in) of armor plating.[4]

Service history

Nassau was ordered under the provisional name Ersatz Bayern, as a replacement for the old Sachsen-class ironclad Bayern. She was laid down on 22 July 1907 at the Kaiserliche Werft in Wilhelmshaven, under construction number 30.[4] Construction work proceeded under absolute secrecy; detachments of soldiers were tasked with guarding the shipyard itself, as well as contractors that supplied building materials, such as Krupp.[10] The ship was launched on 7 March 1908; she was christened by Princess Hilda of Nassau, and the ceremony was attended by Kaiser Wilhelm II and Prince Henry of the Netherlands, representing his wife's House of Orange-Nassau.[11]

Fitting-out work was delayed significantly when a dockyard worker accidentally removed a blanking plate from a large pipe, which allowed a significant amount of water to flood the ship. The ship did not have its watertight bulkheads installed, so the water spread throughout the ship and caused it to list to port and sink 1.6 m (5 ft 3 in) to the bottom of the dock. The ship had to be pumped dry and cleaned out, which proved to be a laborious task.[1] The ship was completed by the end of September 1909. She was commissioned into the High Seas Fleet on 1 October 1909,[4] and trials commenced immediately.[1] HMS Dreadnought, the ship that spurred Nassau's construction, had been launched 25 months before Nassau, on 2 February 1906.[12]

On 16 October 1909, Nassau and her sister Westfalen participated in a ceremony for the opening of the new third entrance in the Wilhelmshaven Naval Dockyard.[13] They took part in the annual maneuvers of the High Seas Fleet in February 1910 while still on trials. Nassau finished her trials on 3 May and joined the newly created I Battle Squadron of the High Seas Fleet. Over the next four years, the ship participated in the regular series of squadron and fleet maneuvers and training cruises. The one exception was the summer training cruise for 1912 when, due to the Agadir Crisis, the cruise only went into the Baltic.[14] On 14 July 1914, the annual summer cruise to Norway began. The threat of war caused Kaiser Wilhelm II to cancel the cruise after two weeks, and by the end of July the fleet was back in port.[15] War between Austria-Hungary and Serbia broke out on the 28th, and in the span of a week all of the major European powers had joined the conflict.[16]

World War I

Nassau participated in most of the fleet advances into the North Sea throughout the war.[17] The first operation was conducted primarily by Rear Admiral Franz von Hipper's battlecruisers; the ships bombarded the English coastal towns of Scarborough, Hartlepool, and Whitby on 15–16 December 1914.[18] A German battlefleet of 12 dreadnoughts—including Nassau—and eight pre-dreadnoughts sailed in support of the battlecruisers. On the evening of 15 December, they came to within 10 nmi (19 km; 12 mi) of an isolated squadron of six British battleships. Skirmishes in the darkness between the rival destroyer screens convinced the German fleet commander, Admiral Friedrich von Ingenohl, that the entire Grand Fleet was deployed before him. Under orders from the Kaiser to not risk the fleet, Ingenohl broke off the engagement and turned the battlefleet back towards Germany.[19]

Battle of the Gulf of Riga

In August 1915, the German fleet attempted to clear the Gulf of Riga to facilitate the capture of Riga by the German Army. To do so, the German planners intended to drive off or destroy the Russian naval forces in the area, which included the pre-dreadnought battleship Slava and a number of gunboats and destroyers. The German naval force would also lay a series of minefields in the northern entrance to the gulf to prevent Russian naval reinforcements from being able to enter the area. The fleet that assembled for the assault included Nassau and her three sister ships, the four Helgoland-class battleships, and the battlecruisers Von der Tann, Moltke, and Seydlitz. The force would operate under the command of now-Vice Admiral Hipper. The eight battleships were to provide cover for the forces engaging the Russian flotilla. The first attempt on 8 August was unsuccessful, as it had taken too long to clear the Russian minefields to allow the minelayer Deutschland to lay a minefield of her own.[20]

On 16 August 1915, a second attempt was made to enter the gulf: Nassau and Posen, four light cruisers, and 31 torpedo boats managed to breach the Russian defenses.[21] On the first day of the assault, the German minesweeper T 46 was sunk, as was the destroyer V 99. The following day, Nassau and Posen engaged in an artillery duel with Slava, resulting in three hits on the Russian ship that forced her to retreat. By 19 August, the Russian minefields had been cleared, and the flotilla entered the gulf. Reports of Allied submarines in the area prompted the Germans to call off of the operation the following day.[22] Nassau and Posen remained in the Gulf until 21 August, and while there assisted in the destruction of the gunboats Sivuch and Korietz.[14] Admiral Hipper later remarked that,

"To keep valuable ships for a considerable time in a limited area in which enemy submarines were increasingly active, with the corresponding risk of damage and loss, was to indulge in a gamble out of all proportion to the advantage to be derived from the occupation of the Gulf before the capture of Riga from the land side."[23]

Battle of Jutland

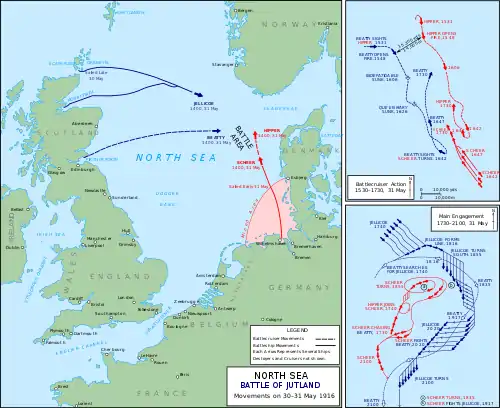

Nassau took part in the inconclusive Battle of Jutland on 31 May – 1 June 1916, in II Division of I Battle Squadron. For the majority of the battle, I Battle Squadron formed the center of the line of battle, behind Rear Admiral Behncke's III Battle Squadron, and followed by Rear Admiral Mauve's elderly pre-dreadnoughts of II Battle Squadron. Nassau was the third ship in the group of four, behind Rheinland and ahead of Westfalen; Posen was the squadron's flagship.[24] When the German fleet reorganized into a nighttime cruising formation, the order of the ships was inadvertently reversed, and so Nassau was the second ship in the line, astern of Westfalen.[25]

Between 17:48 and 17:52, eleven German dreadnoughts, including Nassau, engaged and opened fire on the British 2nd Light Cruiser Squadron; Nassau's target was the cruiser Southampton. Nassau is believed to have scored one hit on Southampton, at approximately 17:50 at a range of 20,100 yd (18,400 m), shortly after she began firing. The shell struck Southampton obliquely on her port side, and did not cause significant damage.[26] Nassau then shifted her guns to the cruiser Dublin; firing ceased by 18:10.[27] At 19:33, Nassau came into range of the British battleship Warspite; her main guns fired briefly, but after the 180-degree turn by the German fleet, the British ship was no longer within reach.[28]

Nassau and the rest of I Squadron were again engaged by British light forces shortly after 22:00, including the light cruisers Caroline, Comus, and Royalist. Nassau followed her sister Westfalen in a 68° turn to starboard in order to evade any torpedoes that might have been fired. The two ships fired on Caroline and Royalist at a range of around 8,000 yd (7,300 m).[29] The British ships turned away briefly, before turning about to launch torpedoes.[30] Caroline fired two at Nassau; the first passed close to her bows and the second passed under the ship without exploding.[31]

At around midnight on 1 June, the German fleet was attempting to pass behind the British Grand Fleet when it encountered a line of British destroyers. Nassau came upon the destroyer Spitfire, and in the confusion, attempted to ram her. Spitfire tried to evade, but could not maneuver away fast enough, and the two ships collided. Nassau fired her forward 11-inch guns at the destroyer. They could not depress low enough for Nassau to be able to score a hit; nonetheless, the blast from the guns destroyed Spitfire's bridge. At that point, Spitfire was able to disengage from Nassau, and took with her a 6 m (20 ft) portion of Nassau's side plating. The collision disabled one of Nassau's 15 cm (5.9 in) guns, and left a 3.5 m (11.5 ft) gash above the waterline; this slowed the ship to 15 knots (28 km/h; 17 mph) until it could be repaired.[32] During the confused action, Nassau was hit by two 4 in (10 cm) shells from the British destroyers, which damaged her searchlights and inflicted minor casualties.[33]

Shortly after 01:00, Nassau and Thüringen encountered the British armored cruiser Black Prince. Thüringen opened fire first, and pummeled Black Prince with a total of 27 heavy-caliber shells and 24 shells from her secondary battery. Nassau and Ostfriesland joined in, followed by Friedrich der Grosse. The heavy fire quickly disabled the British cruiser and set her alight; following a tremendous explosion, she sank, taking her entire crew with her.[34] The sinking Black Prince was directly in the path of Nassau; to avoid the wreck, the ship had to steer sharply towards III Battle Squadron. It was necessary for Nassau to reverse her engines to full speed astern to avoid a collision with Kaiserin. Nassau then fell back into a position between the pre-dreadnoughts Hessen and Hannover.[34] At around 03:00, several British destroyers attempted another torpedo attack on the German line. At approximately 03:10, three or four destroyers appeared in the darkness to port of Nassau; at a range of between 5,500 yd (5,000 m) to 4,400 yd (4,000 m), Nassau briefly fired on the ships before turning away 90° to avoid torpedoes.[35]

Following her return to German waters, Nassau, her sisters Posen and Westfalen, and the Helgoland-class battleships Helgoland and Thüringen, took up defensive positions in the Jade roadstead for the night.[36] In the course of the battle, Nassau was hit twice by secondary shells, though these hits caused no significant damage.[37] Her casualties amounted to 11 men killed and 16 men wounded.[38] During the course of the battle, she fired 106 main battery shells and 75 rounds from her secondary guns.[39] Repairs were completed quickly, and Nassau was back with the fleet by 10 July 1916.[40]

Later operations

Another fleet advance followed on 18–22 August, during which the I Scouting Group battlecruisers were to bombard the coastal town of Sunderland in an attempt to draw out and destroy Beatty's battlecruisers. As only two of the four German battlecruisers were still in fighting condition, three dreadnoughts were assigned to the Scouting Group for the operation: Markgraf, Grosser Kurfürst, and the newly commissioned Bayern. The High Seas Fleet, including Nassau,[14] would trail behind and provide cover.[41] At 06:00 on 19 August, Westfalen was torpedoed by the British submarine HMS E23 55 nautical miles (102 km; 63 mi) north of Terschelling; the ship remained afloat and was detached to return to port.[17] The British were aware of the German plans and sortied the Grand Fleet to meet them. By 14:35, Admiral Scheer had been warned of the Grand Fleet's approach and, unwilling to engage the whole of the Grand Fleet just 11 weeks after the close call at Jutland, turned his forces around and retreated to German ports.[42]

Another sortie into the North Sea followed on 19–20 October. On 21 December, Nassau ran aground in the mouth of the Elbe. She was able to free herself, and repairs were effected in Hamburg at the Reihersteig Dockyard until 1 February 1917.[14] The ship was part of the force that steamed to Norway to intercept a heavily escorted British convoy on 23–25 April, though the operation was canceled when the battlecruiser Moltke suffered mechanical damage and had to be towed back to port.[43] Nassau, Ostfriesland, and Thüringen were formed into a special unit for Operation Schlußstein, a planned occupation of Saint Petersburg. On 8 August, Nassau took on 250 soldiers in Wilhelmshaven and then departed for the Baltic. The three ships reached the Baltic on 10 August, but the operation was postponed and eventually canceled. The special unit was dissolved on 21 August, and the battleships were back in Wilhelmshaven on the 23rd.[44]

Nassau and her three sisters were to have taken part in a final fleet action at the end of October 1918, days before the Armistice was to take effect. The bulk of the High Seas Fleet was to have sortied from their base in Wilhelmshaven to engage the British Grand Fleet; Scheer—by now the Grand Admiral (Großadmiral) of the fleet—intended to inflict as much damage as possible on the British navy, to improve Germany's bargaining position, despite the expected casualties. Many of the war-weary sailors felt that the operation would disrupt the peace process and prolong the war. On the morning of 29 October 1918, the order was given to sail from Wilhelmshaven the following day. Starting on the night of 29 October, sailors on Thüringen and then on several other battleships mutinied. The unrest ultimately forced Hipper and Scheer to cancel the operation.[45]

Fate

Following the German collapse in November 1918, a significant portion of the High Seas Fleet was interned in Scapa Flow. Nassau and her three sisters were not among the ships listed for internment, so they remained at German ports.[2] During this period, from November to December, Hermann Bauer served as the ship's commander.[46] On 21 June 1919, Rear Admiral Ludwig von Reuter, under the mistaken impression that the Armistice would expire at noon that day, ordered his ships be scuttled to prevent their seizure by the British.[47] As a result, the four Nassau-class ships were ceded to the various Allied powers as replacements for the ships that had been sunk.[2] Nassau was awarded to Japan on 7 April 1920, though the Japanese had no need for the ship. They, therefore, sold her in June 1920 to British shipbreakers, who scrapped the ship in Dordrecht.[4]

Notes

Footnotes

- "SMS" stands for "Seiner Majestät Schiff", or "His Majesty's Ship" in German.

- In Imperial German Navy gun nomenclature, "SK" (Schnelladekanone) denotes that the gun quick firing, while "L/45" provides the length of the gun regarding the diameter of the barrel. In this case, the L/45 gun is 45 caliber, which means that the gun is 45 times as long as its diameter.[7]

Citations

- Staff, p. 23.

- Hore, p. 67.

- Dodson, pp. 72–75.

- Gröner, p. 23.

- Herwig, pp. 59–60.

- Staff, pp. 23, 35.

- Grießmer, p. 177.

- Campbell & Sieche, p. 140.

- Staff, p. 22.

- Hough, p. 26.

- Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, p. 135.

- Campbell & Sieche, p. 21.

- Staff, pp. 23–24.

- Staff, p. 24.

- Staff, p. 11.

- Heyman, p. xix.

- Staff, p. 26.

- Tarrant, p. 31.

- Tarrant, pp. 31–33.

- Halpern, pp. 196–197.

- Halpern, p. 197.

- Halpern, pp. 197–198.

- Halpern, p. 198.

- Tarrant, p. 286.

- Tarrant, p. 203.

- Campbell, p. 54.

- Campbell, p. 99.

- Campbell, p. 154.

- Campbell, p. 257.

- Campbell, pp. 257–258.

- Campbell, p. 258.

- Tarrant, p. 220.

- Campbell, p. 287.

- Tarrant, p. 225.

- Campbell, p. 300.

- Tarrant, p. 263.

- Tarrant, p. 296.

- Tarrant, p. 298.

- Tarrant, p. 292.

- Campbell, p. 336.

- Massie, p. 682.

- Massie, p. 683.

- Massie, p. 748.

- Staff, pp. 24, 43–44, 46.

- Tarrant, pp. 280–282.

- Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, p. 133.

- Herwig, p. 256.

References

- Campbell, John (1998). Jutland: An Analysis of the Fighting. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 978-1-55821-759-1.

- Campbell, N. J. M. & Sieche, Erwin (1986). "Germany". In Gardiner, Robert & Gray, Randal (eds.). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1906–1921. London: Conway Maritime Press. pp. 134–189. ISBN 978-0-85177-245-5.

- Dodson, Aidan (2016). The Kaiser's Battlefleet: German Capital Ships 1871–1918. Barnsley: Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84832-229-5.

- Grießmer, Axel (1999). Die Linienschiffe der Kaiserlichen Marine: 1906–1918; Konstruktionen zwischen Rüstungskonkurrenz und Flottengesetz [The Battleships of the Imperial Navy: 1906–1918; Constructions between Arms Competition and Fleet Laws] (in German). Bonn: Bernard & Graefe Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7637-5985-9.

- Gröner, Erich (1990). German Warships: 1815–1945. Vol. I: Major Surface Vessels. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-790-6.

- Halpern, Paul G. (1995). A Naval History of World War I. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-352-7.

- Herwig, Holger (1998) [1980]. "Luxury" Fleet: The Imperial German Navy 1888–1918. Amherst: Humanity Books. ISBN 978-1-57392-286-9.

- Heyman, Neil M. (1997). World War I. Westport: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-29880-6.

- Hildebrand, Hans H.; Röhr, Albert & Steinmetz, Hans-Otto (1993). Die Deutschen Kriegsschiffe (Band 6) [The German Warships (Volume 6)] (in German). Ratingen: Mundus Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7822-0237-4.

- Hore, Peter (2006). Battleships of World War I. London: Southwater Books. ISBN 978-1-84476-377-1.

- Hough, Richard (2003). Dreadnought: A History of the Modern Battleship. Penzance: Periscope Publishing. ISBN 978-1-904381-11-2.

- Massie, Robert K. (2003). Castles of Steel: Britain, Germany, and the Winning of the Great War at Sea. New York City: Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0-345-40878-5.

- Staff, Gary (2010). German Battleships: 1914–1918. Vol. 1: Deutschland, Nassau and Helgoland Classes. Oxford: Osprey Books. ISBN 978-1-84603-467-1.

- Tarrant, V. E. (2001) [1995]. Jutland: The German Perspective. London: Cassell Military Paperbacks. ISBN 978-0-304-35848-9.

Further reading

- Dodson, Aidan; Cant, Serena (2020). Spoils of War: The Fate of Enemy Fleets after the Two World Wars. Barnsley: Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-5267-4198-1.