SMS Hela

SMS Hela was an aviso built for the German Kaiserliche Marine (Imperial Navy) in the mid-1890s, the last vessel of that type to be built by the German Empire. As the culmination of the type in German service, she represented significant improvements over earlier vessels, particularly the Wacht and Meteor classes, which had been disappointments in service. She was intended to serve as a fleet scout and as a flotilla leader for torpedo boats. Hela marked a step toward the development of the light cruiser. Armed with a battery of four 8.8 cm (3.5 in) guns and three 45 cm (17.7 in) torpedo tubes, the ship proved to be too weakly-armed for front-line combat.

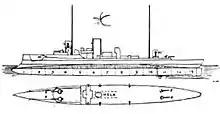

Lithograph of Hela in 1902 | |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Operators | |

| Preceded by | Meteor class |

| Succeeded by | Gazelle class |

| Completed | 1 |

| Lost | 1 |

| History | |

| Name | Hela |

| Builder | AG Weser, Bremen |

| Laid down | December 1893 |

| Launched | 28 March 1895 |

| Commissioned | 3 May 1896 |

| Fate | Sunk, 13 September 1914 |

| General characteristics (as built) | |

| Type | Aviso |

| Displacement | |

| Length | 105 m (344 ft 6 in) overall |

| Beam | 11 m (36 ft 1 in) |

| Draft | 4.64 m (15 ft 3 in) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed | 20 knots (37 km/h; 23 mph) |

| Range | 3,000 nmi (5,600 km; 3,500 mi) at 12 knots (22 km/h; 14 mph) |

| Complement |

|

| Armament |

|

| Armor |

|

Hela had a relatively short active career; engine damage during sea trials shortly after her completion in 1896 delayed the start of her service with the fleet until 1898. She served as a scout for I Squadron from then until 1900, when she was deployed as part of an expeditionary force to help suppress the Boxer Uprising in Qing China. Hela saw little action during the deployment, instead frequently patrolling the coast of China and the Yangtze river. After returning to Germany in mid-1901, she served with I Scouting Group and the main fleet until late 1902, when she was reduced to a gunnery training ship, though boiler problems forced a more thorough reconstruction that lasted from 1903 to 1910.

The ship was used as a tender for the fleet from October 1910 through mid-1914, with few events of note for Hela during this period. Following the outbreak of World War I in July 1914, Hela was deployed to the patrol line guarding the German Bight. She was present at, but was not engaged in, the Battle of Helgoland Bight in August. The next month, while conducting training off Helgoland, she was torpedoed and sunk by the British submarine HMS E9. Despite the fact that Hela sank in less than half an hour, all of her crew, save two men, were rescued by a German U-boat and patrol boat.

Design

Hela, named for the schooner Hela of 1852-vintage, was the culmination in the development of the aviso type in the German fleet. The avisos were developed from earlier torpedo boats and were intended for use in home waters with the fleet, both as flotilla leaders to direct groups of torpedo boats and as scouts for the fleet's capital ships. The first aviso, Zieten, was purchased from a British shipbuilder in 1875; seven more ships were built in German yards by the early 1890s. Of these, the last four vessels, comprising the Wacht and Meteor classes, had proved to be significant disappointments in service, owing to their poor seaworthiness and insufficient speed. In 1893, the naval construction staff prepared a design for a new vessel, provisionally designated "H", which remedied the problems of the earlier vessels, in part through a significant increase in size. This ship became Hela.[1][2]

The aviso type culminated in what would later be referred to as the light cruiser. German designers incorporated the best aspects of Hela's design—primarily a high top speed and an armor deck—with those of their contemporary unprotected cruisers of the Bussard class—namely, a heavy armament and long cruising radius. This combination resulted in the Gazelle-class cruisers, which were the first true light cruisers built in Germany.[3]

General characteristics and machinery

Hela was 104.6 meters (343 ft 2 in) long at the waterline and 105 m (344 ft 6 in) overall. She had a beam of 11 m (36 ft 1 in) and a draft of 4.46 m (14 ft 8 in) forward and 4.64 m (15 ft 3 in) aft. She was designed to displace 2,027 t (1,995 long tons), and at full load the displacement increased to 2,082 t (2,049 long tons). Her hull was constructed with transverse and longitudinal steel frames, which contained twenty-two watertight compartments above the armored deck and ten below. A double bottom ran for thirty-five percent of the length of the hull, which had a pronounced ram bow. The ship had a minimal superstructure, with a small conning tower. A raised forecastle deck extended from the stem to the funnel. She was fitted with a pair of light pole masts fitted with spotting tops.[4]

Hela's crew consisted of 7 officers and 171 enlisted men as completed and later increased to 8 officers and 187 enlisted men. She carried a number of small boats, including one barge, one yawl, and three dinghies. Later in her career, the barge was exchanged for a picket boat. Hela was very seaworthy, but she rolled badly (having a metacentric height of 0.775 m (2 ft 6.5 in)) and tended to ship a significant amount of water in a head sea, owing to the fact that she was slightly bow-heavy. Steering was controlled by a single rudder; she had average maneuverability.[4]

The ship was powered by two 3-cylinder triple-expansion steam engines; each drove a screw propeller that was 3.25 m (10 ft 8 in) in diameter. Each engine had its own separate engine room. The engines were supplied with steam by six locomotive boilers split into two boiler rooms, which were ducted into a single funnel amidships. The engines were rated at 6,000 metric horsepower (5,900 ihp) and a top speed of 20 knots (37 km/h; 23 mph), though on trials they reached a half knot better. Coal storage amounted to 340 long tons (350 t); range figures for the ship in her original configuration have not survived. Hela was equipped with three electrical generators that produced 36 kilowatts at 67 volts.[4]

Armament and armor

Hela was armed with a main battery of four 8.8 cm (3.5 in) SK L/30[Note 1] quick-firing guns in individual mountings. They were carried in MPL C/89 mounts with an elevation range of −10 to 20 degrees; at maximum elevation, the guns could reach targets at 7,300 m (24,000 ft). The guns fired 7 kg (15 lb) projectiles at a muzzle velocity of 590 m/s (1,900 ft/s). These guns were provided with a total of 800 rounds, for 200 per gun.[4][5] Rate of fire was theoretically fourteen shots per minute, but in practice it was limited to ten rounds per minute.[6]

She was also equipped with six 5 cm (2 in) SK L/40 quick-firing guns, each mounted in individual Torpedobootslafette (Torpedo Boat Mount) C/92. These guns fired 1.7 kg (3.8 lb) shells at a muzzle velocity of 2,152 ft/s (656 m/s). Maximum elevation for the guns was twenty degrees, which provided a range of 6,180 m (6,760 yd). Shell storage amounted to 1,500 rounds, or 300 per gun.[4][7] Her armament was completed with three 45 cm (17.7 in) torpedo tubes. Two were placed on the deck on the broadside and the third was submerged in the bow of the ship. These were supplied with a total of eight torpedoes,[4] which carried a 87.5 kg (193 lb) warhead. Their maximum range at 32 knots was 500 m (1,600 ft); when set to 26 kn (48 km/h; 30 mph), their range increased to 800 m (2,600 ft).[8]

Hela was lightly armored. She was protected by an armor deck that was 20 mm (0.79 in) thick and composed of steel. The deck sloped on the sides, and was slightly increased in thickness to 25 mm (0.98 in) to provide a measure of protection against direct fire. An armored coaming that was 40 mm (1.6 in) thick protected the uptakes from the boilers. Her conning tower was armored with 30 mm (1.2 in) thick steel on the sides. She was equipped with cork cofferdams to reduce the ingress of water in the event of hull damage.[4]

Modifications

Hela was modernized in 1903–1910 at the Kaiserliche Werft (Imperial Shipyard) in Danzig. The vessel's internal subdivision was improved with eight additional watertight compartments above the waterline and an extension of the double bottom to cover thirty-nine percent of the hull. As part of the modifications to her hull, both of the broadside torpedo tubes were moved to torpedo rooms below the waterline. She also received eight Marine-type water-tube boilers in place of her old models, and a second funnel was added. The new boilers produced 5,982 metric horsepower (5,900 ihp) on trials, propelling the ship to the same top speed. Coal storage was increased to 412 long tons (419 t), which permitted a cruising radius of 3,000 nautical miles (5,600 km; 3,500 mi) at a speed of 12 knots (22 km/h; 14 mph). Both of her stern 8.8 cm guns were removed and their ammunition allotment was reduced to 156 shells per gun. Her aft superstructure was enlarged to provide additional accommodation space. The ship also received a larger bridge.[4][9]

Service history

Hela was laid down in December 1893 at the AG Weser shipyard in Bremen. She was launched on 28 March 1895 and at the ceremony, Vizeadmiral (Vice Admiral) Victor Valois, the chief of the Marinestation der Nordsee (North Sea Naval Station) christened the ship. She was moved to the {{lang|de|Kaiserliche Werft}} (Imperial Shipyard) in Wilhelmshaven for final fitting out in January 1896. The ship was commissioned for sea trials on 3 May, initially under the command of Korvettenkapitän (KK—Corvette Captain) Johannes Stein, though he was replaced by Kapitänleutnant (KL—Captain Lieutenant) Carl Schönfelder in August. Her initial testing was interrupted by damage to her engines, which necessitated her decommissioning on 19 September for repairs. She spent the next year and a half out of service.[2]

Hela was recommissioned on 10 March 1898, under the command of KK Fritz Sommerwerck, and was assigned to I Squadron to serve as its aviso. These duties were interrupted beginning on 14 June when Hela was chosen to escort Kaiser Wilhelm II aboard his yacht Hohenzollern for sailing regattas in Germany and then a cruise to Norwegian waters in July that included a stop in Hardangerfjord. On 31 July, Hela returned to I Squadron before being detached again on 17 September following the conclusion of the annual fleet maneuvers. She again escorted Hohenzollern with Wilhelm II and his wife Augusta Victoria aboard, along with the protected cruiser Hertha, for a voyage to the eastern Mediterranean Sea. She returned to her unit on 8 December, after which KK Paul Rampold relieved Sommerwerck.[2]

In early 1899, Hela and the rest of I Squadron embarked on a training cruise into the Atlantic. While passing through the English Channel, the ships stopped in Dover, Great Britain, to represent Germany at a celebration for Queen Victoria's 80th birthday on 1 May. In June and July, Hela again escorted Hohenzollern for his summer cruise to Norway; during the fleet maneuvers in August, she operated with the fleet's scouting unit. During the exercises in the Baltic Sea on 28 August, Hela struck the mole outside Neufahrwassar and damaged her starboard propeller. She steamed to Kiel for repairs that were completed by 4 September, allowing her to return to the unit for the rest of the maneuvers. In mid-September, she accompanied Hohenzollern for a cruise to Sweden, and she and the pre-dreadnought battleship Kaiser Friedrich III escorted the Kaiser's yacht on a visit to Britain that lasted from 17 to 30 November. Hela concluded the year with a training cruise with I Squadron in the Skagerrak in December.[10]

Boxer Uprising

Hela spent the first half of 1900 as she had previous years, conducting training exercises with the fleet. Her routine was interrupted by events in Qing China, where on 20 June, during the Boxer Uprising, the German ambassador, Clemens von Ketteler, was murdered by Chinese nationalists. The widespread violence against Westerners in China led to a creation of an alliance between Germany and seven other Great Powers, the so-called Eight-Nation Alliance: the United Kingdom, Italy, Russia, Austria-Hungary, the United States, France, and Japan. Those soldiers who were in China at the time were too few in number to defeat the Boxers; in Beijing there was a force of slightly more than 400 officers and infantry from the armies of the eight European powers. At the time, the primary German military force in China was the East Asia Squadron, which consisted of the protected cruisers Kaiserin Augusta, Hansa, Hertha, and Irene, the unprotected cruiser Gefion, and the gunboats Jaguar and Iltis. There was also a German 500-man detachment in Taku; combined with the other nations' units the force numbered some 2,100 men. These men, led by the British Admiral Edward Seymour, attempted to reach Beijing but were stopped in the Battle of Tientsin.[11][12][13]

As a result, the Kaiser determined an expeditionary force would be sent to China to reinforce the East Asia Squadron. Hela was assigned to the naval expedition on 4 July, which included the four Brandenburg-class battleships, sent to China to reinforce the German squadron there. The ships departed Kiel five days later and arrived off the coast of China in late August. Hela entered the mouth of the Yangtze and then patrolled the Yellow Sea through the end of September. She contributed a landing party consisting of four officers and seventy-four men to participate in the assault on Chinese fortifications at the Shanhai Pass. The aviso spent November anchored in the Wusong roadstead, remaining there until mid-December when she returned to the Yangtze. At the end of the month, she was sent to Shanghai. Hela then returned to the Yangtze in January 1901, stopping in Zhenjiang, before returning to Shanghai in February and remaining there into March. At that time, KK Maximilian von Spee arrived to take command of the vessel from Rampold. She later visited the German concession at Qingdao before returning to Shanghai at the end of May. While there, she received orders to return to Germany, and KK Joachim von Bredow took command of the vessel for the voyage home. On 1 June she and the rest of the expeditionary force departed to return home, arriving in Wilhelmshaven on 11 August.[2]

1901–1913

.jpg.webp)

After returning from China, Hela immediately participated in the annual fleet maneuvers, serving for the duration with I Scouting Group from 26 August to 19 September. She joined the unit again for a voyage to Oslo, Norway in mid-December, arriving back in Wilhelmshaven on the 16th. Hela returned to service with the main fleet in 1902, and while on a cruise in the Atlantic in May, she was detached to escort the light cruiser Amazone, which had been damaged off the Sevenstones Lightship. By this time, the German naval command had decided that Hela was too weakly-armed to be useful as a fleet scout, and so she was sent to the Kaiserliche Werft in Kiel on 16 October to be modernized for use as a training ship for light guns. While in the shipyard, Hela passed from Bredow's command to KK Karl Zimmerman's. The work was completed on 21 December and she was recommissioned for this duty on 31 January 1903, but the poor condition of the ship's boilers required further modifications, which were carried out at the Kaiserliche Werft in Danzig beginning on 25 April. The aviso Blitz replaced Hela in her intended role.[14]

Some ship location reports in the German archives in the Bundesarchiv-Militärarchiv (German Federal Military Archive) indicate that Hela was in service with I Scouting Group from June to September 1903, but the naval historians Hans Hildebrand, Albert Röhr, and Hans-Otto Steinmetz have been unable to locate any official records of her commissioning or decommissioning during this period, nor of who commanded the vessel during this time. No logbook exists in the archives either. According to the location reports, the vessel was to have ended this period in Wilhelmshaven, but no records follow for the transfer to Danzig, where it is definitively known that the ship was reconstructed. Hildebrand, Röhr, and Steinmetz have nevertheless been unable to determine how the mistake continued for several months, or what ship is actually represented in the reports.[9]

Hela remained in the shipyard in Danzig until 1910, where she underwent a significant reconstruction. She was recommissioned on 1 October and conducted a brief set of sea trials from 14 to 18 October. The ship was thereafter employed as a fleet tender. While on maneuvers on the night of 29–30 March 1911, the torpedo boat S121 inadvertently crossed too closely in front of Hela, which struck the torpedo boat with her bow. Neither vessel was seriously damaged in the collision. In April, KK Theodor Püllen became the ship's captain, serving until October. After that year's fleet maneuvers in August and September, the navy conducted a fleet review for the visit of the Austro-Hungarian Marinekommandant (Naval Commander), Admiral Rudolf Montecuccoli. Hela then carried Montecuccoli to visit Wilhelmshaven and the island of Helgoland. The next two years passed uneventfully; she was transferred to Kiel on 1 April 1912. In September, KK Carl-Wilhelm Weniger took command of the ship. In mid-1913, the Italian Vice Admiral Prince Luigi Amedeo, Duke of the Abruzzi visited Germany, and on 31 May, she carried him for a visit to Helgoland, where the fleet was anchored. In September, KK Paul Wolfram relieved Weniger; Wolfram was to be the vessel's last commander.[15]

World War I

Following the start of World War I in July 1914, Hela was brought back to active duty and assigned to IV Scouting Group. The unit was tasked with supporting the German torpedo boats that formed the outer ring of coastal scouting patrols in the German Bight. She was modified slightly between 13 and 16 August, having a third 8.8 cm gun installed. Hela was stationed to the northeast of Helgoland, along with the cruiser Stettin.[9][16]

On 28 August, British cruisers and destroyers from the Harwich Force surprised and attacked the German patrol line, resulting in the Battle of Helgoland Bight. Hela's commander received reports of the fighting and turned east to reinforce the vessels engaged in the action. While en route, the ship received a contradictory report that stated that the British vessels were retreating, leading now Fregattenkapitän (Frigate Captain) Wolfram to reverse course and return to his assigned location. As a result, she was not engaged in the action. Later that night, she regrouped with the cruisers Kolberg and München to provide cover for the remaining torpedo boats and reestablish the Bight patrol line.[17][18]

Two weeks later, on the morning of 13 September, Hela was attacked 6 nautical miles (11 km; 6.9 mi) southwest of Helgoland by the British submarine HMS E9 under command of the future Admiral Max Horton.[19] Hela was conducting a training exercise at the time; the area around Helgoland was presumed safe from British submarines.[20] After surfacing, E9 spotted the German cruiser and immediately re-submerged to fire two of her torpedoes, one of which struck Hela's stern. After 15 minutes, E9 rose to periscope depth to inspect the scene. The British submarine found Hela sinking. Within another 15 minutes, Hela had slipped beneath the waves.[9][21] Despite the speed with which the ship sank, her entire crew, with the exception of two sailors, were rescued from the sea by the U-boat U-18 and one of the coastal patrol vessels.[4][9]

Hela was the first German ship sunk by a British submarine in the war.[22] As a result of her loss, all German ships conducting training exercises were moved to the Baltic Sea to prevent further such sinkings.[20] One of her 8.8 cm guns was retrieved from the wreck and is now preserved at Fort Kugelbake in Cuxhaven.[23]

Footnotes

Notes

- In Imperial German Navy gun nomenclature, "SK" (Schnellladekanone) denotes that the gun is quick firing, while the L/30 denotes the length of the gun. In this case, the L/30 gun is 30 calibers, meaning that the gun barrel is 30 times as long as it is in diameter.

Citations

- Lyon, pp. 249, 256–258.

- Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, pp. 108–109.

- Nottelmann 2020, pp. 102–104.

- Gröner, p. 99.

- Friedman, p. 146.

- Nottelmann 2002, p. 137.

- Friedman, p. 147.

- Friedman, p. 336.

- Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, p. 110.

- Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, p. 109.

- Bodin, pp. 1, 5–6, 11–12.

- Holborn, p. 311.

- Harrington, p. 29.

- Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, pp. 108–110.

- Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, pp. 108, 110.

- Osborne, p. 56.

- Osborne, pp. 60, 76–77, 102.

- Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, p. 108.

- Halpern, p. 33.

- Gunton, p. 28.

- The Independent, p. 9.

- Thomas, p. 130.

- Mehl, p. 79.

References

- Bodin, Lynn E. (1979). The Boxer Rebellion. London: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-0-85045-335-5.

- Friedman, Norman (2011). Naval Weapons of World War One: Guns, Torpedoes, Mines and ASW Weapons of All Nations; An Illustrated Directory. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-84832-100-7.

- Gröner, Erich (1990). German Warships: 1815–1945. Vol. I: Major Surface Vessels. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-790-6.

- Gunton, Michael (2005). Submarines at War: A History of Undersea Warfare from the American Revolution to the Cold War. New York City: Carroll & Graf Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7867-1455-1.

- Halpern, Paul G. (1995). A Naval History of World War I. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-352-4.

- Harrington, Peter (2001). Peking 1900: The Boxer Rebellion. London: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-84176-181-7.

- Hildebrand, Hans H.; Röhr, Albert & Steinmetz, Hans-Otto (1993). Die Deutschen Kriegsschiffe: Biographien: ein Spiegel der Marinegeschichte von 1815 bis zur Gegenwart (Band 4) [The German Warships: Biographies: A Reflection of Naval History from 1815 to the Present (Vol. 4)] (in German). Ratingen: Mundus Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7822-0382-1.

- Holborn, Hajo (1982). A History of Modern Germany: 1840–1945. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-00797-7.

- Lyon, Hugh (1979). "Germany". In Gardiner, Robert; Chesneau, Roger; Kolesnik, Eugene M. (eds.). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1860–1905. Greenwich: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 978-0-85177-133-5.

- Mehl, Hans (2002). Naval Guns: 500 Years of Ship and Coastal Artillery. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-557-8.

- Nottelmann, Dirk (2002). Die Brandenburg-Klasse: Höhepunkt des deutschen Panzerschiffbaus [The Brandenburg Class: High Point of German Armored Ship Construction] (in German). Hamburg: Mittler. ISBN 3813207404.

- Nottelmann, Dirk (2020). "The Development of the Small Cruiser in the Imperial German Navy". In Jordan, John (ed.). Warship 2020. Oxford: Osprey. pp. 102–118. ISBN 978-1-4728-4071-4.

- Osborne, Eric W. (2006). The Battle of Heligoland Bight. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-34742-8.

- Thomas, Lowell (2002). Raiders of the Deep. Garden City: Periscope Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-1-904381-03-7.

- "The Story of the Week". The Independent. New York: Independent Publications. 90: 7–11. 1914.