S5 (classification)

S5, SB4, SM5 are disability swimming classifications used for categorizing swimmers based on their level of disability. The class includes people with a moderate level of disability, and includes people with full use of their arms and hands, but limited to no use of their trunk and legs. It also includes people with coordination problems. A variety of disabilities are represented by this class including people with cerebral palsy. The class competes at the Paralympic Games.

Definition

This classification is for swimming.[1] In the classification title, S represents Freestyle, Backstroke and Butterfly strokes. SB means breaststroke. SM means individual medley.[1] Swimming classifications are on a gradient, with one being the most severely physically impaired to ten having the least amount of physical disability.[2][3] Jane Buckley, writing for the Sporting Wheelies, describes the swimmers in this classification as having: "full use of their arms and hands but no trunk or leg muscles; Swimmers with coordination problems."[1]

Disability groups

This class includes people with several disability types include cerebral palsy, short stature and amputations.[4][5][6]

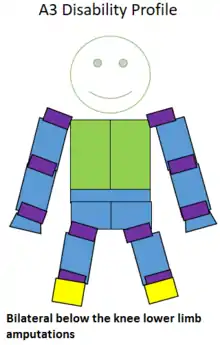

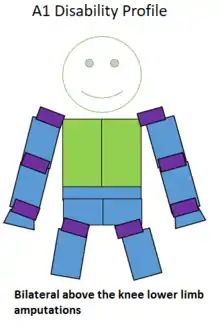

Amputee

ISOD amputee A1, A3 and A9 swimmers may be found in this class.[6] Prior to the 1990s, the A1, A3 and A9 classes were often grouped with other amputee classes in swimming competitions, including the Paralympic Games.[7]

Lower body amputations

A1 and A3 swimmers in this class have a similar stroke length and stroke rate to able bodied swimmers.[8] A study comparing the performance of swimming competitors at the 1984 Summer Paralympics found there was no significant difference in performance in times between men and women in A2 and A3 in the 50 meter breaststroke, men and women in A2 and A3 in the 50 meter freestyle, men and women in A2, A3 and A4 in the 25 meter butterfly, and men in A2 and A3 in the 50 meter backstroke.[7]

The nature of an A3 swimmer's amputations in this class can affect their physiology and sports performance.[9][10][11] Because of the potential for balance issues related to having an amputation, during weight training, amputees are encouraged to use a spotter when lifting more than 15 pounds (6.8 kg).[9] Lower limb amputations affect a person's energy cost for being mobile. To keep their oxygen consumption rate similar to people without lower limb amputations, they need to walk slower.[11] A3 swimmers use around 41% more oxygen to walk or run the same distance as someone without a lower limb amputation.[11] A1 swimmers use around 120% more oxygen to walk or run the same distance as someone without a lower limb amputation.[11]

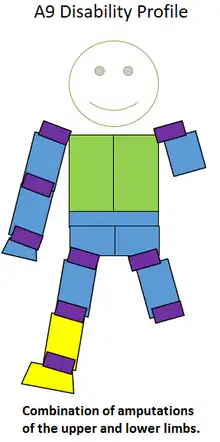

Upper and lower limb amputations

ISOD amputee A9 swimmers may be found in several classes. These include S2, S3, S4, S5 and S8.[12][13] Prior to the 1990s, the A9 class was often grouped with other amputee classes in swimming competitions, including the Paralympic Games.[7] Swimmers in this class have a similar stroke length and stroke rate to able bodied swimmers.[8]

The nature of a person's amputations in this class can affect their physiology and sports performance.[9][11] Because of the potential for balance issues related to having an amputation, during weight training, amputees are encouraged to use a spotter when lifting more than 15 pounds (6.8 kg).[9] Lower limb amputations affect a person's energy cost for being mobile. To keep their oxygen consumption rate similar to people without lower limb amputations, they need to walk slower.[11] Because they are missing a limb, amputees are more prone to overuse injuries in their remaining limbs. Common problems with intact upper limbs for people in this class include rotator cuffs tearing, shoulder impingement, epicondylitis and peripheral nerve entrapment.[11]

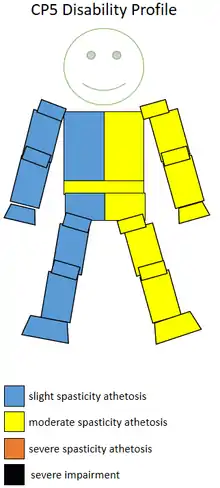

Cerebral palsy

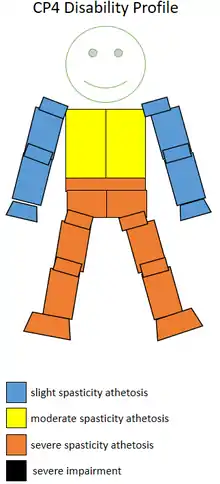

One of the disability groups in this classification is swimmers with cerebral palsy, including CP4 and CP5 classified swimmers.[14]

Because of their balance issues, CP4 and CP5 swimmers in this class can find the starting block problematic and often have slower times entering the water than other competitors in their class.[15] Because the disability of swimmers in the CP4 and CP5 classes that involve in a loss of function in specific parts of their body, they are more prone to injury than their able-bodied counterparts as a result of overcompensation in other parts of their body.[4] When fatigued, asymmetry in their stroke becomes a problem for swimmers for CP4 and CP5 swimmers.[4] The integrated classification system used for swimming, where swimmers with CP compete against those with other disabilities, is subject to criticisms has been that the nature of CP is that greater exertion leads to decreased dexterity and fine motor movements. This puts competitors with CP at a disadvantage when competing against people with amputations who do not lose coordination as a result of exertion.[16]

On a daily basis, CP4 sportspeople in this class are likely to use a wheelchair. Some may be ambulant with the use of assistive devices.[17] They have minimal control problems in upper limbs and torso, and good upper body strength.[17][18][19] Head movement and trunk function differentiate this class from CP3. Lack of symmetry in arm movement are another major difference between the two classes, with CP3 competitors having less symmetry.[20]

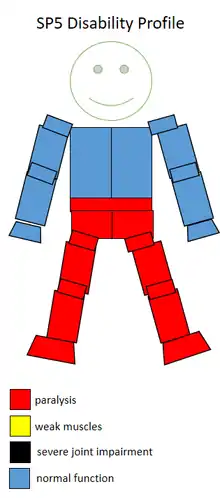

CP5 sportspeople in this class have greater functional control of their upper body. They may require the use of an assistive device when walking but they do not require use of a wheelchair.[17][19][21] They often have problems with their dynamic equilibrium but not their static equilibrium.[22][23] Quick movements can upset their balance.[22][23]

CP4 swimmers tend to have a passive normalized drag in the range of 0.7 to 0.9. This puts them into the passive drag band of PDB6.[24] CP5 swimmers tend to have a passive normalized drag in the range of 0.6 to 1.0. This puts them into the passive drag band of PDB5, PDB6, PDB7, PDB8, and PDB9.[25]

Short stature

SS2 swimmers may be found S1 and S5.[26] Men in this class are 130 centimetres (51 in) tall or less, with an arm length equal to or less than 59 centimetres (23 in). When their standing height and arm length are added together, the distance is equal to or less than 180 centimetres (71 in). For women in this class, the same measurements are 125 centimetres (49 in), 57 centimetres (22 in) and 173 centimetres (68 in).[17][27]

S5 swimmers with short stature have a height less than 130 cm for women and 137 cm for men. They have an additional disability that creates problem with their propulsion. Because they have intact hands, they can catch water correctly for propulsion. They have full trunk control and usually have symmetrical kicks with their feet but their trunk movements can reduce their propulsion. As they get up to speed, this movement causes turbulence which slows them down and they need additional strokes to compensate. They generally start from the diving platform, though a few swimmers require assistance. They also tend to use a standard kick turn.[28]

There are generally two types of syndromes that cause short stature. One is disproportionate limb size on a normal size torso. The second is proportionate, where they are generally small for their average age. There are a variety of causes including skeletal dysplasia, chondrodystrophy, and growth hormone deficiencies. Short stature can cause a number of other disabilities including eye problems, joint defects, joint dislocation or limited range of movement.[29]

Spinal cord injuries

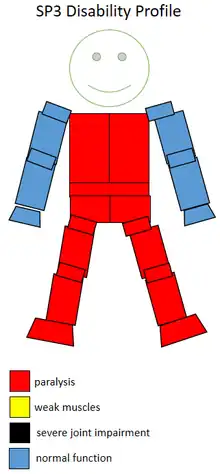

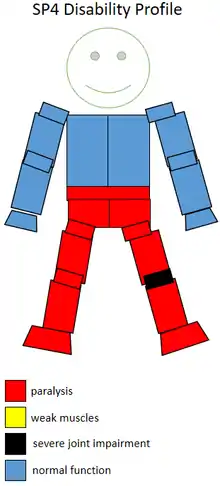

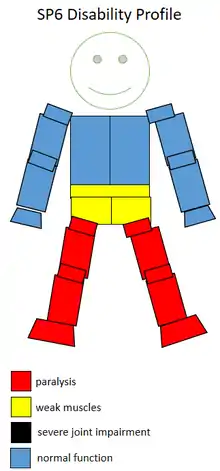

People with spinal cord injuries compete in this class, including F3, F4, F5, F6 and F7 sportspeople.[30][31][32]

F3

This is wheelchair sport classification that corresponds to the neurological level C8.[33][34] In the past, this class was known as 1C Complete, and 1B Incomplete.[33][34] Disabled Sports USA defined the anatomical definition of this class in 2003 as, "Have full power at elbow and wrist joints. Have full or almost full power of finger flexion and extension. Have functional but not normal intrinsic muscles of the hand (demonstrable wasting)."[34] People with a lesion at C8 have an impairment that affects the use of their hands and lower arm.[35] Disabled Sports USA defined the functional definition of this class in 2003 as, "Have nearly normal grip with non-throwing arm."[34] They have full functional control or close to full functional control over the muscles in their fingers, but may have issues with control in their wrist and hand.[34][36] People in this class have a total respiratory capacity of 79% compared to people without a disability.[37]

Swimming classification is done based on a total points system, with a variety of functional and medical tests being used as part of a formula to assign a class. Part of this test involves the Adapted Medical Research Council (MRC) scale. For upper trunk extension, C8 complete are given 0 points.[38]

S5 swimmers with spinal cord injuries tend to be complete paraplegics with lesions below T1 to T8, or incomplete tetraplegics below C8 who have decent trunk control. These swimmers have full use of their arms and are able to use their arms, hands and fingers to gain propulsion in the catch phase of swimming. Because they have minimal trunk control, their hips tend to be a bit lower in the water and they have leg drag. They either start in the water or start from a sitting dive position. They use their hands to make turns.[39]

For swimming with the most severe disabilities at the 1984 Summer Paralympics, floating devices and a swimming coach in the water swimming next to the Paralympic competitor were allowed.[40] A study comparing the performance of athletics competitors at the 1984 Summer Paralympics found there was little significant difference in performance times between women in 1A (SP1, SP2), 1B (SP3), and 1C (SP3, SP4) in the 25m breaststroke. It found there was little significant difference in performance times between women in 1A, 1B, and 1C in the 25m backstroke. It found there was little significant difference in performance times between women in 1A, 1B, and 1C in the 25m freestyle. It found there was little significant difference in performance times between men in 1A, 1B, and 1C in the 25m backstroke. It found there was little significant difference in performance times between men in 1A, 1B, and 1C in the 25m freestyle. It found there was little significant difference in performance times between men in 1A, and 1B in the 25m breaststroke.[7]

F4

This is wheelchair sport classification that corresponds to the neurological level T1- T7.[34][41] In the past, this class was known as 1C Incomplete, 2 Complete, or Upper 3 Complete.[34][41] F4 sportspeople may have good sitting balance and some impairment in their dominant hand.[42] Disabled Sports USA defined the functional definition of this class in 2003 as, "Have no sitting balance. [...] Usually hold onto part of the chair while throwing. Complete Class 2 and upper Class 3 Athletes have normal upper limbs. They can hold the throwing implement normally. They have no functional trunk movements.Incomplete 1C Athletes who have trunk movements, with hand function like F3."[34] People in this class have a total respiratory capacity of 85% compared to people without a disability.[37]

S5 swimmers with spinal cord injuries tend to be complete paraplegics with lesions below T1 to T8, or incomplete tetraplegics below C8 who have decent trunk control. These swimmers have full use of their arms and are able to use their arms, hands and fingers to gain propulsion in the catch phase of swimming. Because they have minimal trunk control, their hips tend to be a bit lower in the water and they have leg drag. They either start in the water or start from a sitting dive position. They use their hands to make turns.[43]

A study comparing the performance of athletics competitors at the 1984 Summer Paralympics found there was little significant difference in performance times between women in 1A (SP1, SP2), 1B (SP3), and 1C (SP3, SP4) in the 25m breaststroke. It found there was little significant difference in performance times between women in 1A, and 1C in the 25m backstroke. It found there was little significant difference in performance times between women in 1A, 1B, and 1C in the 25m freestyle. It found there was little significant difference in performance times between men in 1A, 1B, and 1C in the 25m backstroke. It found there was little significant difference in performance times between men in 1A, 1B, and 1C in the 25m freestyle. It found there was little significant difference in performance times between women in 2 and 3 in the 50m breaststroke. It found there was little significant difference in performance times between men in 2 (SP4) and 3 (SP4, SP5) in the 50m breaststroke. It found there was little significant difference in performance times between women in 2 (SP4) and 3 (SP4, SP5) in the 50m freestyle. It found there was little significant difference in performance times between men in 2 and 3 in the 50m freestyle. It found there was little significant difference in performance times between men in 2 (SP4) and 3 (SP4, SP5) in the 50m backstroke. It found there was little significant difference in performance times between women in 2, 3 and 4 in the 25 m butterfly. It found there was little significant difference in performance times between men in 2, 3 and 4 in the 25 m butterfly.[7]

F5

This is wheelchair sport classification that corresponds to the neurological level T8 - L1.[34][44] In the past, this class was known as Lower 3, or Upper 4.[34][44] Disabled Sports USA defined the anatomical definition of this class in 2003 as, "Normal upper limb function. Have abdominal muscles and spinal extensors (upper or more commonly upper and lower). May have non-functional hip flexors (grade 1). Have no abductor function."[34]

People in this class have good sitting balance.[45][46] People with lesions located between T9 and T12 have some loss of abdominal muscle control.[46] Disabled Sports USA defined the functional definition of this class in 2003 as, "Three trunk movements may be seen in this class: 1) Off the back of a chair (in an upwards direction). 2) Movement in the backwards and forwards plane. 3) Some trunk rotation. They have fair to good sitting balance. They cannot have functional hip flexors, i.e. ability to lift the thigh upwards in the sitting position. They may have stiffness of the spine that improves balance but reduces the ability to rotate the spine."[34]

Swimming classification is done based on a total points system, with a variety of functional and medical tests being used as part of a formula to assign a class. Part of this test involves the Adapted Medical Research Council (MRC) scale. For upper trunk extension, T6 - T10 are given 3 - 5 points.[47]

S5 swimmers with spinal cord injuries tend to be complete paraplegics with lesions below T1 to T8, or incomplete tetraplegics below C8 who have decent trunk control. These swimmers have full use of their arms and are able to use their arms, hands and fingers to gain propulsion in the catch phase of swimming. Because they have minimal trunk control, their hips tend to be a bit lower in the water and they have leg drag. They either start in the water or start from a sitting dive position. They use their hands to make turns.[48] People in SB5 tend to be complete paraplegics below T11 to L1 who cannot use their legs for swimming, or complete paraplegics at L2 to L3 with surgical rods put in their spinal column from T4 to T6 which affects their balance.[48]

A study was done comparing the performance of athletics competitors at the 1984 Summer Paralympics. It found there was little significant difference in performance times between women in 2 (SP4) and 3 (SP4, SP5) in the 50m breaststroke. It found there was little significant difference in performance times between men in 2 (SP4) and 3 (SP4, SP5) in the 50m breaststroke. It found there was little significant difference in performance times between women in 2 (SP4) and 3 (SP4, SP5) in the 50m freestyle. It found there was little significant difference in performance times between men in 2 (SP4) and 3 (SP4, SP5) in the 50m freestyle. It found there was little significant difference in performance times between men in 2 (SP4) and 3 (SP4, SP5) in the 50m backstroke. It found there was little significant difference in performance times between women in 4 (SP5, SP6), 5 (SP6, SP7) and 6 (SP7) in the 100m breaststroke. It found there was little significant difference in performance times between women in 4 (SP5, SP6), 5 (SP6, SP7) and 6 (SP7) in the 100m backstroke. It found there was little significant difference in performance times between women in 4 (SP5, SP6), 5 (SP6, SP7) and 6 (SP7) in the 100m freestyle. It found there was little significant difference in performance times between women in 4 (SP5, SP6), 5 (SP6, SP7) and 6 (SP7) in the 14 x 50 m individual medley. It found there was little significant difference in performance times between men in 4 (SP5, SP6), 5 (SP6, SP7) and 6 (SP7) in the 100m backstroke. It found there was little significant difference in performance times between men in 4 (SP5, SP6), 5 (SP6, SP7) and 6 (SP7) in the 100m breaststroke. It found there was little significant difference in performance times between women in 2 (SP4), 3 (SP4, SP5) and 4 (SP5, SP6) in the 25 m butterfly. It found there was little significant difference in performance times between men in 2 (SP4), 3 (SP4, SP5) and 4 (SP5, SP6) in the 25 m butterfly.[7]

F6

This is wheelchair sport classification that corresponds to the neurological level L2 - L5.[34][49] Historically, this class has been known as Lower 4, Upper 5.[34][49] People with lesions at L4 have issues with their lower back muscles, hip flexors and their quadriceps.[31] People with lesions at the L4 to S2 who are complete paraplegics may have motor function issues in their gluts and hamstrings. Their quadriceps are likely to be unaffected. They may be absent sensation below the knees and in the groin area.[50]

People in this class have good sitting balance.[51] People with lesions at L4 have trunk stability, can lift a leg and can flex their hips. They can walk independently with the use of longer leg braces. They may use a wheelchair for the sake of convenience. Recommended sports include many standing related sports.[31] People in this class have a total respiratory capacity of 88% compared to people without a disability.[37]

People in SB5 tend to be complete paraplegics below T11 to L1 who cannot use their legs for swimming, or complete paraplegics at L2 to L3 with surgical rods put in their spinal column from T4 to T6 which affects their balance.[52]

A study was done comparing the performance of athletics competitors at the 1984 Summer Paralympics. It found there was little significant difference in performance times between women in 4 (SP5, SP6), 5 (SP6, SP7) and 6 (SP7) in the 100m breaststroke. It found there was little significant difference in performance times between women in 4 (SP5, SP6), 5 (SP6, SP7) and 6 (SP7) in the 100m backstroke. It found there was little significant difference in performance times between women in 4 (SP5, SP6), 5 (SP6, SP7) and 6 (SP7) in the 100m freestyle. It found there was little significant difference in performance times between women in 4 (SP5, SP6), 5 (SP6, SP7) and 6 (SP7) in the 14 x 50 m individual medley. It found there was little significant difference in performance times between men in 4 (SP5, SP6), 5 (SP6, SP7) and 6 (SP7) in the 100m backstroke. It found there was little significant difference in performance times between men in 4 (SP5, SP6), 5 (SP6, SP7) and 6 (SP7) in the 100m breaststroke. It found there was little significant difference in performance times between women in 2 (SP4), 3 (SP4, SP5) and 4 (SP5, SP6) in the 25 m butterfly. It found there was little significant difference in performance times between men in 2 (SP4), 3 (SP4, SP5) and 4 (SP5, SP6) in the 25 m butterfly. It found there was little significant difference in performance times between women in 5 (SP6, SP7) and 6 (SP7) in the 50 m butterfly. It found there was little significant difference in performance times between men in 5 (SP6, SP7) and 6 (SP7) in the 4 x 50 m individual medley. It found there was little significant difference in performance times between men in 5 (SP6, SP7) and 6 (SP7) in the 100 m freestyle.[7]

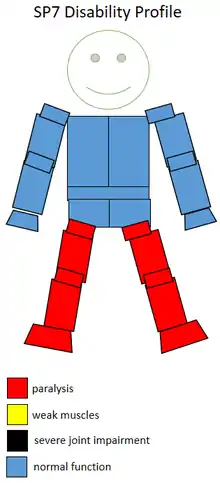

F7

F7 is wheelchair sport classification, that corresponds to the neurological level S1- S2.[34][53] Historically, this class has been called Lower 5.[34][53] In 2002, USA Track & Field defined this class as, " These athletes also have the ability to move side to side, so they can throw across their body. They usually can bend one hip backward to push the thigh into the chair, and can bend one ankle downward to push down with the foot. Neurological level: S1-S2."[54]

People with a lesion at S1 have their hamstring and peroneal muscles affected. Functionally, they can bend their knees and lift their feet. They can walk on their own, though they may require ankle braces or orthopedic shoes. They can generally change in any physical activity.[31] People with lesions at the L4 to S2 who are complete paraplegics may have motor function issues in their gluts and hamstrings. Their quadriceps are likely to be unaffected. They may be absent sensation below the knees and in the groin area.[50]

Disabled Sports USA defined the functional definition of this class in 2003 as, "Have very good sitting balance and movements in the backwards and forwards plane. Usually have very good balance and movements towards one side (side to side movements) due to presence of one functional hip abductor, on the side that movement is towards. Usually can bend one hip backwards; i.e. push the thigh into the chair. Usually can bend one ankle downwards; ie. push the foot onto the foot plate. The side that is strong is important when considering how much it will help functional performance."[34]

F7 swimmers competing as S10 tend to have lesions at S1 or S2 that has minimal effect on their lower limbs. This is often caused by polio or cauda-equina syndrome. Swimmers in this class lack full propulsion in their kicks because of a slight loss of function in one limb. They do a standing start and kick turns, but get less power than they might otherwise because of the leg impairment.[55]

History

The classification was created by the International Paralympic Committee and has roots in a 2003 attempt to address "the overall objective to support and co-ordinate the ongoing development of accurate, reliable, consistent and credible sport focused classification systems and their implementation."[56]

In 1997, New Zealand S5 competitors tended to be complete paraplegics.[3]

Events

Events open to people in this class include the 50m and 100m Freestyle, 200m Freestyle, 50m Backstroke, 50m Butterfly, 100m Breaststroke and 200m Individual Medley events.[57]

At the Paralympic Games

For this classification, organisers of the Paralympic Games have the option of including the following events on the Paralympic programme: 50m and 100m Freestyle, 200m Freestyle, 50m Backstroke, 50m Butterfly, 100m Breaststroke and 200m Individual Medley events.[57]

For the 2016 Summer Paralympics in Rio, the International Paralympic Committee had a zero classification at the Games policy. This policy was put into place in 2014, with the goal of avoiding last minute changes in classes that would negatively impact athlete training preparations. All competitors needed to be internationally classified with their classification status confirmed prior to the Games, with exceptions to this policy being dealt with on a case-by-case basis.[58]

Records

In both the S5 50 m and 100 m Freestyle Long Courses, the men's world record is held by Brazil's Daniel Dias and the women's world record is held by Spain's Teresa Perales.[59][60]

Getting classified

Swimming classification generally has three components. The first is a bench press. The second is water test. The third is in competition observation.[61] As part of the water test, swimmers are often required to demonstrate their swimming technique for all four strokes. They usually swim a distance of 25 meters for each stroke. They are also generally required to demonstrate how they enter the water and how they turn in the pool.[62]

Classification generally has four phase. The first stage of classification is a health examination. For amputees in this class, this is often done on site at a sports training facility or competition. The second stage is observation in practice, the third stage is observation in competition and the last stage is assigning the sportsperson to a relevant class.[63] Sometimes the health examination may not be done on site for amputees in this class because the nature of the amputation could cause not physically visible alterations to the body.[15]

In Australia, to be classified in this category, athletes contact the Australian Paralympic Committee or their state swimming governing body.[64] In the United States, classification is handled by the United States Paralympic Committee on a national level. The classification test has three components: "a bench test, a water test, observation during competition."[65] American swimmers are assessed by four people: a medical classified, two general classified and a technical classifier.[65]

Competitors

Swimmers who have competed in this classification include Olena Akopyan,[66] Dmytro Kryzhanovskyy[66] and Inbal Pezaro[66] who all won medals in their class at the 2008 Paralympics.[66] American swimmers who have been classified by the United States Paralympic Committee as being in this class include Matthew Papenheim, Ty Payne and Roy Perkins.[67]

References

- Buckley, Jane (2011). "Understanding Classification: A Guide to the Classification Systems used in Paralympic Sports". Archived from the original on 11 April 2011. Retrieved 12 November 2011.

- Shackell, James (2012-07-24). "Paralympic dreams: Croydon Hills teen a hotshot in pool". Maroondah Weekly. Archived from the original on 2012-12-04. Retrieved 2012-08-01.

- Gray, Alison (1997). Against the odds : New Zealand Paralympians. Auckland, N.Z.: Hodder Moa Beckett. p. 18. ISBN 1869585666. OCLC 154294284.

- Scott, Riewald; Scott, Rodeo (2015-06-01). Science of Swimming Faster. Human Kinetics. ISBN 9780736095716.

- Tim-Taek, Oh; Osborough, Conor; Burkett, Brendan; Payton, Carl (2015). "Consideration of Passive Drag in IPC Swimming Classification System" (PDF). VISTA Conference. International Paralympic Committee. Retrieved July 24, 2016.

- Tim-Taek, Oh; Osborough, Conor; Burkett, Brendan; Payton, Carl (2015). "Consideration of Passive Drag in IPC Swimming Classification System" (PDF). VISTA Conference. International Paralympic Committee. Retrieved July 24, 2016.

- van Eijsden-Besseling, M. D. F. (1985). "The (Non)sense of the Present-Day Classification System of Sports for the Disabled, Regarding Paralysed and Amputee Athletes". Paraplegia. International Medical Society of Paraplegia. 23. Retrieved July 25, 2016.

- Vanlandewijck, Yves C.; Thompson, Walter R. (2011-07-13). Handbook of Sports Medicine and Science, The Paralympic Athlete. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781444348286.

- "Classification 101". Blaze Sports. Blaze Sports. June 2012. Retrieved July 24, 2016.

- DeLisa, Joel A.; Gans, Bruce M.; Walsh, Nicholas E. (2005-01-01). Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation: Principles and Practice. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 9780781741309.

- Miller, Mark D.; Thompson, Stephen R. (2014-04-04). DeLee & Drez's Orthopaedic Sports Medicine. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 9781455742219.

- Tim-Taek, Oh; Osborough, Conor; Burkett, Brendan; Payton, Carl (2015). "Consideration of Passive Drag in IPC Swimming Classification System" (PDF). VISTA Conference. International Paralympic Committee. Retrieved July 24, 2016.

- "ritgerd". www.ifsport.is. Archived from the original on 2016-05-05. Retrieved 2016-07-25.

- Tim-Taek, Oh; Osborough, Conor; Burkett, Brendan; Payton, Carl (2015). "Consideration of Passive Drag in IPC Swimming Classification System" (PDF). VISTA Conference. International Paralympic Committee. Retrieved July 24, 2016.

- Gilbert, Keith; Schantz, Otto J.; Schantz, Otto (2008-01-01). The Paralympic Games: Empowerment Or Side Show?. Meyer & Meyer Verlag. ISBN 9781841262659.

- Richter, Kenneth J.; Adams-Mushett, Carol; Ferrara, Michael S.; McCann, B. Cairbre (1992). "llntegrated Swimming Classification : A Faulted System" (PDF). Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly. 9: 5–13. doi:10.1123/apaq.9.1.5.

- "CLASSIFICATION SYSTEM FOR STUDENTS WITH A DISABILITY". Queensland Sport. Queensland Sport. Archived from the original on April 4, 2015. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- "Clasificaciones de Ciclismo" (PDF). Comisión Nacional de Cultura Física y Deporte (in Mexican Spanish). Mexico: Comisión Nacional de Cultura Física y Deporte. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- "Kategorie postižení handicapovaných sportovců". Tyden (in Czech). September 12, 2008. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- "CLASSIFICATION AND SPORTS RULE MANUAL" (PDF). CPISRA. CPISRA. January 2005. Retrieved July 22, 2016.

- "Classification Made Easy" (PDF). Sportability British Columbia. Sportability British Columbia. July 2011. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- "Clasificaciones de Ciclismo" (PDF). Comisión Nacional de Cultura Física y Deporte (in Mexican Spanish). Mexico: Comisión Nacional de Cultura Física y Deporte. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- Cashman, Richmard; Darcy, Simon (2008-01-01). Benchmark Games. Benchmark Games. ISBN 9781876718053.

- Tim-Taek, Oh; Osborough, Conor; Burkett, Brendan; Payton, Carl (2015). "Consideration of Passive Drag in IPC Swimming Classification System" (PDF). VISTA Conference. International Paralympic Committee. Retrieved July 24, 2016.

- Tim-Taek, Oh; Osborough, Conor; Burkett, Brendan; Payton, Carl (2015). "Consideration of Passive Drag in IPC Swimming Classification System" (PDF). VISTA Conference. International Paralympic Committee. Retrieved July 24, 2016.

- Tim-Taek, Oh; Osborough, Conor; Burkett, Brendan; Payton, Carl (2015). "Consideration of Passive Drag in IPC Swimming Classification System" (PDF). VISTA Conference. International Paralympic Committee. Retrieved July 24, 2016.

- MD, Michael A. Alexander; MD, Dennis J. Matthews (2009-09-18). Pediatric Rehabilitation: Principles & Practices, Fourth Edition. Demos Medical Publishing. ISBN 9781935281658.

- International Paralympic Committee (February 2005). "SWIMMING CLASSIFICATION CLASSIFICATION MANUAL" (PDF). International Paralympic Committee Classification Manual. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-11-04.

- McKeag, Douglas; Moeller, James L. (2007-01-01). ACSM's Primary Care Sports Medicine. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 9780781770286.

- International Paralympic Committee (February 2005). "SWIMMING CLASSIFICATION CLASSIFICATION MANUAL" (PDF). International Paralympic Committee Classification Manual. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-11-04.

- Winnick, Joseph P. (2011-01-01). Adapted Physical Education and Sport. Human Kinetics. ISBN 9780736089180.

- Tim-Taek, Oh; Osborough, Conor; Burkett, Brendan; Payton, Carl (2015). "Consideration of Passive Drag in IPC Swimming Classification System" (PDF). VISTA Conference. International Paralympic Committee. Retrieved July 24, 2016.

- Consejo Superior de Deportes (2011). Deportistas sin Adjectivos (PDF) (in European Spanish). Spain: Consejo Superior de Deportes. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-11-04. Retrieved 2016-08-03.

- National Governing Body for Athletics of Wheelchair Sports, USA. Chapter 2: Competition Rules for Athletics. United States: Wheelchair Sports, USA. 2003.

- Arenberg, Debbie Hoefler, ed. (February 2015). Guide to Adaptive Rowing (PDF). US Rowing.

- International Paralympic Committee (February 2005). "SWIMMING CLASSIFICATION CLASSIFICATION MANUAL" (PDF). International Paralympic Committee Classification Manual. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-11-04.

- Woude, Luc H. V.; Hoekstra, F.; Groot, S. De; Bijker, K. E.; Dekker, R. (2010-01-01). Rehabilitation: Mobility, Exercise, and Sports : 4th International State-of-the-Art Congress. IOS Press. ISBN 9781607500803.

- International Paralympic Committee (February 2005). "SWIMMING CLASSIFICATION CLASSIFICATION MANUAL" (PDF). International Paralympic Committee Classification Manual. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-11-04.

- International Paralympic Committee (February 2005). "SWIMMING CLASSIFICATION CLASSIFICATION MANUAL" (PDF). International Paralympic Committee Classification Manual. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-11-04.

- Broekhoff, Jan (1986-06-01). The 1984 Olympic Scientific Congress proceedings: Eugene, Ore., 19-26 July 1984 : (also: OSC proceedings). Human Kinetics Publishers. ISBN 9780873220064.

- Consejo Superior de Deportes (2011). Deportistas sin Adjectivos (PDF) (in European Spanish). Spain: Consejo Superior de Deportes. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-11-04. Retrieved 2016-08-03.

- IWAS (20 March 2011). "IWF RULES FOR COMPETITION, BOOK 4 – CLASSIFICATION RULES" (PDF).

- International Paralympic Committee (February 2005). "SWIMMING CLASSIFICATION CLASSIFICATION MANUAL" (PDF). International Paralympic Committee Classification Manual. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-11-04.

- Consejo Superior de Deportes (2011). Deportistas sin Adjectivos (PDF) (in European Spanish). Spain: Consejo Superior de Deportes. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-11-04. Retrieved 2016-08-03.

- IWAS (20 March 2011). "IWF RULES FOR COMPETITION, BOOK 4 – CLASSIFICATION RULES" (PDF).

- Arenberg, Debbie Hoefler, ed. (February 2015). Guide to Adaptive Rowing (PDF). US Rowing.

- International Paralympic Committee (February 2005). "SWIMMING CLASSIFICATION CLASSIFICATION MANUAL" (PDF). International Paralympic Committee Classification Manual. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-11-04.

- International Paralympic Committee (February 2005). "SWIMMING CLASSIFICATION CLASSIFICATION MANUAL" (PDF). International Paralympic Committee Classification Manual. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-11-04.

- Consejo Superior de Deportes (2011). Deportistas sin Adjectivos (PDF) (in European Spanish). Spain: Consejo Superior de Deportes. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-11-04. Retrieved 2016-08-03.

- Goosey-Tolfrey, Vicky (2010-01-01). Wheelchair Sport: A Complete Guide for Athletes, Coaches, and Teachers. Human Kinetics. ISBN 9780736086769.

- IWAS (20 March 2011). "IWF RULES FOR COMPETITION, BOOK 4 – CLASSIFICATION RULES" (PDF).

- International Paralympic Committee (February 2005). "SWIMMING CLASSIFICATION CLASSIFICATION MANUAL" (PDF). International Paralympic Committee Classification Manual. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-11-04.

- Consejo Superior de Deportes (2011). Deportistas sin Adjectivos (PDF) (in European Spanish). Spain: Consejo Superior de Deportes. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-11-04. Retrieved 2016-08-03.

- "SPECIAL SECTION ADAPTATIONS TO USA TRACK & FIELD RULES OF COMPETITION FOR INDIVIDUALS WITH DISABILITIES" (PDF). USA Track & Field. USA Track & Field. 2002.

- International Paralympic Committee (February 2005). "SWIMMING CLASSIFICATION CLASSIFICATION MANUAL" (PDF). International Paralympic Committee Classification Manual. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-11-04.

- "Paralympic Classification Today". International Paralympic Committee. 22 April 2010. p. 3.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - "Swimming Classification". The Beijing Organizing Committee for the Games of the XXIX Olympiad. 2008. Archived from the original on 14 March 2012. Retrieved 18 November 2011.

- "Rio 2016 Classification Guide" (PDF). International Paralympic Committee. International Paralympic Committee. March 2016. Retrieved July 22, 2016.

- "IPC Swimming World Records Long Course". International Paralympic Committee. Archived from the original on 19 May 2012. Retrieved 18 November 2011.

- "IPC Swimming World Records Long Course". International Paralympic Committee. Archived from the original on 19 May 2012. Retrieved 18 November 2011.

- "CLASSIFICATION GUIDE" (PDF). Swimming Australia. Swimming Australia. Retrieved June 24, 2016.

- "Classification Profiles" (PDF). Cerebral Palsy International Sports and Recreation Association. Cerebral Palsy International Sports and Recreation Association. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 18, 2016. Retrieved July 22, 2016.

- Tweedy, Sean M.; Beckman, Emma M.; Connick, Mark J. (August 2014). "Paralympic Classification: Conceptual Basis, Current Methods, and Research Update". Paralympic Sports Medicine and Science. 6 (85). Retrieved July 25, 2016.

- "Classification Information Sheet" (PDF). Australian Paralympic Committee. 8 March 2011. p. 3. Retrieved 17 November 2011.

- "U.S. Paralympics National Classification Policies & Procedures SWIMMING". United States Paralympic Committee. 26 June 2011. Retrieved 18 November 2011.

- "Results". International Paralympic Committee. Retrieved 18 November 2011.

- "USA NATIONAL CLASSIFICATION DATABASE" (PDF). United States Paralympic Committee. 7 October 2011. Retrieved 18 November 2011.

.svg.png.webp)