Robert Boyd (university principal)

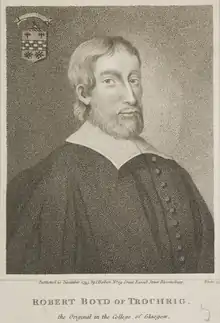

Robert Boyd of Trochrig (1578–1627) was a Scottish theological writer, teacher and poet. He studied at the University of Edinburgh and after attending lectures by Robert Rollock, prosecuted his studies in France, and became a minister in the French Church. All accounts represent him as a most accomplished scholar. A friend said of him, with perhaps some exaggeration, that he was more eloquent in French than in his native tongue; and Livingstone tells us that he spoke Latin with perfect fluency, but that he had heard him say, if he had his choice, he would rather express himself in Greek than in any other language. The Church of Boyd's adoption, which had given Andrew Melville a chair in one university, and Sharp a chair in another, was not slow to do honour to their brilliant countryman. He was made a professor in the protestant Academy of Saumur; and there for some years he taught theology. He was persuaded, however, in 1614 to come home and accept the Principalship of the Glasgow University. Though he was far from extreme in his Presbyterianism, he was found to be less tractable than the king and his advisers expected, and was obliged to resign his office. But he was long enough in Glasgow to leave the impress of himself on some of the young men destined to distinction in the Church in after years.[1]

Robert Boyd | |

|---|---|

Robert Boyd, Principal of the University of Glasgow, 1615-1621 and Principal of the University of Edinburgh, 1622-1623 | |

| Church | Church of Scotland |

| Orders | |

| Ordination | 1604 |

| Personal details | |

| Born | ca 1578 |

| Died | 15 January 1627 (aged 48–49) Edinburgh, Scotland |

| Alma mater | University of Edinburgh |

He was Principal of the University of Glasgow from 1615 to 1621 and the University of Edinburgh from 1622 to 1623. He was expelled from these positions due to his opposition to the 1618 Five Articles of Perth and died in Edinburgh on 15 January 1627.

Personal life

Robert Boyd was the eldest son of Margaret Chalmers and James Boyd of Trochrig, Archbishop of Glasgow and Chancellor of the University of Glasgow from 1572-1581.[2] He was a great-grandson of Robert Boyd, 1st Lord Boyd and connected to the Cassilis family, later the Marquesses of Ailsa.

When Robert was three, his father died and Margaret took him and his brother Thomas to live on an estate in Ayrshire, variously spelled Trochrig, Trochridge, and Trochorege. The two sons, Robert and Thomas, received their early education at Ayr Grammar School. From there Robert proceeded to Edinburgh University and graduated M.A. in 1595.[3][4] During his time in Edinburgh his elder brother Thomas died, leaving him heir to the family estate.[3]

In 1591 Margaret and her family were kidnapped by Hew Kennedy of Girvanmains and imprisoned for a while in Dalquharran Castle.[5] Robert studied theology at the University of Edinburgh, where he was taught by the Presbyterian Robert Rollock and graduated in 1594.[6]

He went to France and taught at Tours. He later became Professor of Philosophy (Arts) at Montauban, 1599-1604 and subsequently minister at Verteuil, 1604-6. He was translated to Saumur in 1606 becoming Professor of Divinity there in 1608.

He married at Saumur, May 1611, Anna, daughter of Sir Patrick Maliverne of Viniola, knight and they had children — Robert; John of Trochrig; Anne; Margaret and Janet.[7] Only 2 children survived, John and Lucretia; after his death in 1627, she married George Sibbald, a long-time friend.[8] She died sometime before 14 December 1654.[7]

King James VI saw to it that he was appointed Principal of Glasgow University and he took up the post in January 1615. He was elected to Greyfriars' Parish, Edinburgh, 18 October 1622, with the Principalship of Edinburgh University in conjunction. He was demitted in 1623. He moved to Paisley and was admitted on 1 January 1626. He demitted in August that year, having been assaulted.[7]

He retired to Trochrig, and died in Edinburgh (where he had gone for medical advice) of a malignant growth in the throat, 5 January 1627.[7]

Career

The Reformation in Scotland created a national Church of Scotland or kirk that was Calvinist in doctrine and Presbyterian in structure. Many Scots studied or taught in French Huguenot universities and in May 1597, Boyd did the same; he spent most of the next three years in Bordeaux and Thouars, until he was offered the position of Professor of Philosophy at the university of Montauban in 1600.[9]

He still wanted to preach and in 1604 became minister for the Reformed Church in Verteuil-sur-Charente; however, his scholastic reputation was such he was persuaded in 1605 to accept a position as Professor of Philosophy at the Academy of Saumur, then Professor of Divinity in 1608.[2] Saumur was the centre of Amyraldism, a distinctive form of Calvinism taught by Moses Amyraut but inspired by John Cameron (1580–1625), a Scot from Glasgow.

This was a period of intense conflict over religion; the 1562-1598 French Wars of Religion caused around three million deaths from war and disease, surpassed only by those of the 1618-1648 Thirty Years' War, one of the most destructive conflicts in recorded history, with an estimated eight million, mostly inhabitants of the Holy Roman Empire.[10] In Britain, similar arguments over religious practices would ultimately lead to the 1638-1652 Wars of the Three Kingdoms.

James VI, the son of Mary Queen of Scots was brought up in Stirling under the tutelage of George Buchanan. Like most Scots, James was a Calvinist but he favoured rule by bishops or Episcopalian governance as a means of control; when he also became King of England in 1603, creating a unified Church of Scotland and England was the first step towards a centralised, Unionist state.[11] However, the Church of England was very different from the kirk in both governance and doctrine and even Scottish bishops viewed many English practices as essentially Catholic.[12]

Despite his father being an archbishop, Boyd was opposed to any form of Episcopalianism; in 1610, he visited Scotland and in a letter dated 12 July to a colleague in France, wrote that James' decision to establish the Episcopall hierarchy throu all his countreys (sic) would ...force in Popery, Atheisime, ignorance and impiety.[13] Although friends and relatives urged him to return to Scotland, Boyd decided to remain in France but in 1614, James asked him to become Principal at the University of Glasgow and he felt obliged to accept.[6]

Shortly after his arrival in Glasgow, religious tensions were raised by the public execution on 10 March 1615 of the Jesuit convert, John Ogilvie. Ogilvie, who was ostensibly tried for treachery, was of particular concern since he came from an upper class, Calvinist Scots family and studied at the Protestant University of Helmstedt before his conversion.[14]

His execution fed into the debate over James' proposed reforms or the Five Articles of Perth, which reflected long-standing divisions over the Scottish Reformation. The article which caused the greatest objection was kneeling during the Eucharist, which some viewed as idolatry. Even those who did not argued Olgivie's case showed the danger of conversion to Catholicism, even for the educated devout.

In 1618, the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland reluctantly approved the Articles but Boyd was one of those who opposed them and they were widely resented.[15] In March 1620, John Fergushill and 48 other ministers were summoned to appear before the Scottish High Commission, an ecclesiastical court of bishops and sympathetic ministers established to enforce the Articles. The accused were found guilty but all denied the authority of the Court to discipline them; Fergushill was a long-standing family connection whom Boyd had mentored since 1604 and he wrote a letter to the Court on his behalf, urging clemency.[16]

This made Boyd an obvious target and in 1621, he was forced to resign from Glasgow University; in October 1622, he was offered the position of Principal at Edinburgh University and Minister at Greyfriars Kirk.[17][4] Both appointments were blocked by James; Edinburgh was the most important outlet in Scotland for public information and the kirk there was under huge pressure to appoint only ministers willing to conform.[18]

At the time of the previous minister's resignation, the Earl of Abercorn was absent from Paisley, and for some time Mr. Boyd, though strongly urged thereto by Lord Ross of Hawkhead and others, hesitated to allow himself to be appointed minister of the town.[19] He was related to the Abercorns, and some years previously had been a frequent visitor at the Place of Paisley, but was far from sure as to how his acceptance of the appointment would be taken by the Earl and his mother, Marion Boyd, the Dowager Countess, who had recently become a Catholic.[20] Her son Claud Hamilton, with some others, broke into Boyd's house, throwing his books and household contents into the street.[6] Later, when Boyd was leaving, "the rascally women of the town not only upbraided Mr. Robert with opprobrious speeches, and shouted and hoyed him, but likewise cast stones and dirt at him." The Privy Council had these outrages before them, but nothing was done except to exact a pledge from the Abercorn family to offer no further hindrance to the minister.[21][22] There were calls to summon several of the women before Presbytery but nothing came of it.[23] Shaken by this and suffering from ill-health, Boyd retired once more to Trochrig; he died in January 1627 while visiting Edinburgh.

Works

Boyd's major work was an elaborate 'Commentary on the Epistle to the Ephesians', not published until 1652 and described as a theological thesaurus. His Latin poem Hecatombe ad Christum Salvatorem was included by Sir John Scot of Scotstarvet in his Delicias Poetarum Scotorum, reprinted at Edinburgh by Robert Sibbald, nephew of Dr. George Sibbald, who later married his widow Ann.

Walker says that Boyd's great work is his Commentary on the Epistle to the Ephesians. He says that as a work it is of stupendous size and stupendous learning. There is more in it than in the four quarto tomes of Turretin. Its apparatus criticus is something enormous. The Greek and Latin Fathers; the writers of the dark ages; the Protestant and Romish theologians of his own time; Justin and Irenaeus; Tertullian and Cyprian; Clement and Origen; Augustine and Jerome; Gregory Nyssen and Gregory Nazianzen; Anselm, and Bonaventure, and Bernard; Calvin and Rollock; Bellarmine and Pighius, — are all at hand to render aid or to receive replies. In one sense, Boyd on the Ephesians is a commentary, that is to say, the author discusses the meaning of every verse and clause, and does so well. But much more properly it might be called a theological thesaurus. You have a separate discussion of almost every important theological topic. The Trinity, the Incarnation, Original Sin, Baptism, Arianism, Ubiquitarianism, the Nature and Extent of Redemption, are all fully handled. There is a treatise on Predestination which alone would make a considerable volume. One can only regret that a selection of these separate essays or discussions was not published, rather than the huge indiscriminate mass, which has led to the calamitous result of a great divine being buried under his own erudition.[24]

Reid's Works of Robert Boyd of Trochrigg:

- I. Roberti Bodii a Trochoregia Scoti, SS. Theologiae in Academiis Salmuriana, Glascuana, et Edinburgena Professoris eximii, in Epistolam Pauli Apostoli ad Ephesios Praelectiones supra CC. . . . Opus Posthumum. . . . Londini : impensis Societatis Stationariorum 1652. [Dedication by Boyd's son to the Reformed Pastors and Professors of France and Scotland : Life by A. Rivet : Letter to the reader, by Robert Baillie. 1245 pp folio],

- 2. Roberti Bodii a Trochoregia Hecatombe Christiana. [In Johnston's Delitiae Poetarum Scotorum, 12mo. 2 vols. 1637, vol. ii. 209-219. A hundred Latin verses in praise of Christ our Saviour.]

- 3. Monita de filii sui primogeniti institutione, ex Authoris M.S. autographis per R(obertum) S(ibbaldum), M.D., edita, Edin., 8vo. 1701. [A short paper on the education of his eldest son, edited by Dr. Sibbald.] Reprinted in Wodrow (Life of Boyd, App. xvii. Maitland Club). Wodrow gives a list of unprinted MSS. (Life of Boyd, p. 256, 257.) These include the Philotheca a fragment of autobiography in Latin verse.

- Hecatombe ad Christum Servatorem (Edinburgh, 1627., 1825) ;

- A Spirituall Hymne, or the Sacrifice of a Sinner, to be offered upon the Altar of a Humbled Heart to Christ our Redeemer, Inverted in English Sapphicks, from the Latin of that Revered, Religious, and Learned Divine, Mr Robert Boyd [by Sir William Mure, younger of Rowallan] (Edinburgh, 1628) ;

- In Epistolam Pauli Apostoli ad Ephesios Praelectiones (London, 1652 ; Geneva, 1661) ; Monita de filii sui primogenita institutione (Edinburgh, 1701);

- Ode, "D. Georgio Sibbaldo, M.D." (Del.Poetar. Scot., A., 209);

- "Verses to King James " (Muse's Welcome) ;

- Extracts from Obituary (Bannatyne Miscell., i).

- He left in MSS., Sermons, 3 vols. ; Apodyterium ;

- Sermons in French, several vols. ;

- Philotheca.

Bibliography

Reid's Bibliography for the Life of Boyd

- 1. Wodrow's Lives II. Wodrow Society.

- 2. Dictionary of National Biog. sub voce.

- 3. Munimenta Almae Univ. Glasguensis.

- 4. Delitiae Poet. Scot, (for Boyd's poem Ad Christum Servatorem Hecatombe). (See also Wodrow, Life of Boyd, Appendix.)

- 5. Scott's Fasti, sub Paisley.

- 6. Records of University of Edinburgh.

- 7. A. Rivet's Life of Boyd, prefixed to Boyd on Ephesians.

- 8. M'Ure's Glasgow.

- 9. Row's History.

- 10. Wodrow's Lives of Blair and Livingstone.

- 11. Baillie's Letters and Journals.

- 12. Dr. Milroy (of Moneydie) — Lee Lecture, 1891.

- 13. Dempster, Hist. Eccl. Gentis Scotorum, Bannat. Club, 1829.

Scott's bibliography:

- Glasg. Reg. (Marr.) ;

- Glasg. Tests. ;

- Wodrow Biog., ii. ;

- Baillie's Lett., iii., 226;

- Inq. Ret. Ayr, 99, 345, Gen., 3973;

- Robertson's Ayr, iii., 307;

- P. C. Reg., i., 309, 421, 422;

- Rivet's Life of Boyd ;

- Dict. Nat. Biog. ;

- Reid's Divinity

References

- Walker 1888, p. 4.

- UofG 2008.

- Campbell 1956, p. 221.

- Pbarnaby 2017.

- Masson 1881, p. 669-670.

- Marshall 2008.

- Scott 1920, p. 163.

- Mullan 2000, p. 222-223.

- Wodrow 1834, p. 16.

- Wilson, Peter (2009). Europe's Tragedy: A New History of the Thirty Years War (2010 ed.). Penguin. p. 787. ISBN 978-0-14-100614-7.

- Stephen, Jeffrey (January 2010). "Scottish Nationalism and Stuart Unionism". Journal of British Studies. 49 (1, Scottish Special): 55–58. doi:10.1086/644534. S2CID 144730991.

- McDonald, Alan (1998). The Jacobean Kirk, 1567–1625: Sovereignty, Polity and Liturgy. Routledge. pp. 75–76. ISBN 185928373X.

- Wodrow 1834, p. 84.

- Smith 1885–1900.

- Mitchison, Rosalind (2002). A History of Scotland. Routledge. pp. 166–168. ISBN 0415278805.

- Houlbrooke, Ralph (ed), Stewart, Laura (author) (2006). Propaganda, Public Opinion and the Perth Articles Debate in James VI and I: Ideas, Authority, and Government. Routledge. pp. 151–152. ISBN 0754654109. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

{{cite book}}:|last1=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Scott 1915, p. 45.

- Houlbrooke, Ralph (ed), Stewart, Laura (author) (2006). Propaganda, Public Opinion and the Perth Articles Debate in James VI and I: Ideas, Authority, and Government. Routledge. p. 162. ISBN 0754654109. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

{{cite book}}:|last1=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Reid 1917, p. 164-166.

- Metcalfe 1909, p. 229.

- Reid 1917, p. 165.

- Masson 1899, p. 422.

- Metcalfe 1909, p. 231.

- Walker 1888, p. 5.

Sources

- Anderson, William (1877). "Boyd, Robert". The Scottish nation: or, The surnames, families, literature, honours, and biographical history of the people of Scotland. Vol. 1. A. Fullarton & co. pp. 366–367.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Blaikie, William Garden (1885–1900). . Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Blair, Robert; Row, William; M'Crie, Thomas (1848). The life of Mr. Robert Blair, minister of St. Andrews, containing his autobiography, from 1593-1636 : with supplement of his life and continuation of the history of the times, to 1680. Edinburgh: Wodrow Society. pp. 9–10. Retrieved 15 July 2019.

- Brown, Robert (1886). The history of Paisley, from the Roman period down to 1884. Vol. 1. Paisley: J. & J. Cook. pp. 83–84. Retrieved 15 July 2019.

- Campbell, William M. (1956). Robert Boyd of Trochrigg. Scottish Church History Society. Retrieved 14 July 2019.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Chambers, Robert; Thomson, Thomas (1857). A biographical dictionary of eminent Scotsmen. New ed., rev. under the care of the publishers. With a supplementary volume, continuing the biographies to the present time. Vol. 1. Glasgow: Blackie. pp. 298–300. Retrieved 20 April 2019.

- Fairley, John A. (1922). Extracts for the Records of the Old Tolbooth. Vol. 11. Edinburgh: Old Edinburgh Club. p. 35. Retrieved 15 July 2019.

- Howie, John; Carslaw, W. H. (1870). "Robert Boyd". The Scots worthies. Edinburgh: Oliphant, Anderson, & Ferrier. pp. 139–142.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Macpherson, John; McCrie, C. G. (1903). Doctrine of the church in Scottish theology : the sixth series of the Chalmers Lectures. Edinburgh: Macniven & Wallace. pp. 24–31. Retrieved 13 July 2019.

- Marshall, Rosalind (2008). "Robert Boyd; 1578-1627". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/3112. Retrieved 18 September 2018. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Masson, David, ed. (1881). The register of the Privy Council of Scotland. Vol. 4. Edinburgh: H.M. General Register House. pp. 669–670. Retrieved 13 July 2019.

- Masson, David, ed. (1899). The register of the Privy Council of Scotland. 2. Vol. 1. Edinburgh: H.M. General Register House. pp. 309, 421–422. Retrieved 13 July 2019.

- M'Crie, Thomas (1850). Sketches of Scottish church history : embracing the period from the Reformation to the Revolution. Edinburgh: Johnstone & Hunter. pp. 183–184. Retrieved 15 July 2019.

- Metcalfe, William Musham (1909). A history of Paisley, 600-1908. Paisley: Alexander Gardner. pp. 428–432. Retrieved 15 July 2019.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Mullan, David George (2000). Scottish Puritanism, 1590-1638. OUP. pp. 222–223. ISBN 0198269978. Retrieved 15 July 2019.

- Murray, David (1919). "Ninian Campbell of Kilmacolm, Professor of Eloquence at Saumur, Minister of Kilmacolm and of Rosneath". The Scottish Historical Review. 17: 184–188. Retrieved 15 July 2019.

- Pannier, Jacques (1935). Scots in Saumur in the 17th century. Scottish Church History Society. pp. 141–142. Retrieved 15 July 2019.

- Pbarnaby (6 January 2017). "Robert Boyd (1578-1627)". Our History. University of Edinburgh. Retrieved 13 July 2019.

- Reid, Henry Martin Beckwith (1917). The divinity principals in the University of Glasgow. Glasgow: J. Maclehose. pp. 1–82. Retrieved 9 July 2019.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Scott, Hew (1915). Fasti ecclesiae scoticanae; the succession of ministers in the Church of Scotland from the reformation. Vol. 1. Edinburgh: Oliver and Boyd. p. 45. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Scott, Hew (1920). Fasti ecclesiae scoticanae; the succession of ministers in the Church of Scotland from the reformation. Vol. 3. Edinburgh: Oliver and Boyd. pp. 162–163, 410. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Smith, George Gregory (1885–1900). . Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- UofG (18 July 2008). "Robert Boyd of Trochrig". The University of Glasgow Story. University of Glasgow. Retrieved 13 July 2019.

- Walker, James (1888). The theology and theologians of Scotland : chiefly of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries (2nd ed.). Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark. pp. 4–6, 17, 37, 49, 53, 61. Retrieved 22 April 2017.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Walker, Norman Lockhart (1882). Scottish church history. Vol. 8. Edinburgh: T. & T. Clarke. Retrieved 15 July 2019.

- Wodrow, Robert (1834). Duncan, William J (ed.). Collections upon the lives of the reformers and most eminent ministers of the Church of Scotland. Vol. 2. Glasgow: Maitland Club. p. 16.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.