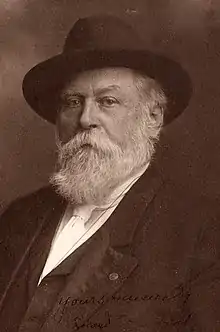

Ricard O'Sullivan Burke

Ricard O'Sullivan Burke (24 January 1838 – 11 May 1922) was an Irish nationalist, Fenian activist, Union American Civil War soldier, U.S. Republican Party campaigner, and a public-works engineer. Travelling extensively, he performed various jobs. He was involved in two prison escape attempts, in Manchester, where a policeman was shot dead, and in London, where twelve passers-by were blown up.

Ricard O'Sullivan Burke | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 24 January 1838 |

| Died | 11 May 1922 (aged 84) Chicago, Illinois |

| Resting place | Mount Olivet Cemetery, Chicago |

| Nationality | Irish |

| Citizenship | American |

| Occupation | public works engineer |

Early life

Burke was born on 24 January 1838 at Cloonareague, Kinneigh (Irish: Cluain Aimhréidh, Cinn Eich), in County Cork, Ireland. He was the youngest of twelve children born to Margaret (née O'Sullivan) and Denis Burke. The family was evicted from their farm by Lord Bandon possibly after Denis Burke supported the Chartist former member of parliament Feargus O'Connor. John Devoy wrote that Denis Burke was a civil engineer. The family moved to Dunmanway where Burke attended the National School and Model School. At age 15, he enrolled in the Cork Militia and remained there for three years. One account reports him as a militia "sergeant"[1] and another as "corporal".[2] Some accounts say he deserted the army, either because an officer struck him[2] or because he was disillusioned.[1] He joined family members in London; after failing to find work, he left England for the US, possibly to avoid court-martial. Devoy said that Burke was actually ashamed to go home as the Militia had dissolved in 1856 - it had effectively been a recruiting ground for the Crimean War (now ended, hence the dissolution) and was full of "corner-boys, tinkers and wastrels".[3] He did odd jobs in New York, apparently including painting a portrait from a photo in Harlem. The client, a sea captain, gave him work as a deckhand or supercargo on his trading vessel. This fuelled tales of his romantic exploits: he allegedly gained "a mastery of seamanship" and "a fluency in the Spanish language"; he stopped for a year in Paris for linguistics and art studies; he prospected for gold in California, leading a band of sailors north and debarking at Cabo San Lucas, Baja California. Later, he continued overland to South America, surviving poison-laced wine and eventually joining a mostly-Irish militia or cavalry in Chile fighting native Americans. In 1861, he returned to New York.[2][4][5]

Career

Accounts differ, but Burke enlisted with 15th Regiment of the New York State Volunteers (N.Y.S.V.) on the 17 June 1861, and is in the roster titled 'Fifteenth engineers' among those published in 1893 and 1905.[6][7] The 15th N.Y.S.V. received instruction in army engineering (they were known as "sappers") at Alexandria, Virginia and were associated with works like trenches, barriers, bridges etc. around various engagements including Yorktown, Gettysburg and Petersburg.[8] He was never hurt: only 5 of the regiment died in action; 124 perished from disease etc. Devoy reported that he demustered in Virginia on 13 June 1865, having been granted the rank of brevet colonel. John Joseph Corydon, a witness for the prosecution in his trial in London in 1868, said he knew Burke as a sergeant in the Federal army in 1862 and that Burke became a lieutenant, then a captain. This is confirmed in army records: one document held in public records in Chicago records him as a 2nd lieutenant (also held there is his citizenship document, dated 1865); the New York State Military Museum record indicates his sequence of ranks in different companies until - on 13 June - mustering out as captain at Fort Berry, Virginia.[3][9][7]

After mustering out, he offered his services to John O'Mahony (head of the Fenian Brotherhood in New York), biding his time working as a bookkeeper before being sent to Ireland some months later. Once there, Thomas Kelly (who ousted James Stephens as head of the Irish Republican Brotherhood) sent him to England to purchase arms, but funding was hampered by Fenian divisions in the U.S. He returned to New York in 1866, and was back in Ireland at the start of 1867 for the Fenian rising (in charge of Waterford), which was a failure.[3] On 13 April, the Jacmel under Captain Cavanagh put to sea from New York loaded with thousands of guns and forty Fenians. Rebadged as Erin's Hope mid-Atlantic, it anchored off the County Sligo coast. Signals to shore from the vessel were ignored. It is not clear if Burke boarded the ship or Cavanagh went ashore, but Burke told Cavanagh the rising was a flop. Thirty men who went ashore in Waterford were arrested. The ship avoided capture and returned to the US, its cargo of weapons intact.[10][11]

Arrests and escape attempts

On 27 November 1867, Burke was arrested by police related to an incident involving Joseph Theobald Casey in St Pancras, London. He gave the name 'George Berry'. After some inquiries, it was established who he was. In February 1868, he was indicted at Warwick Spring Assizes with Casey and a Harry Mullady, who had been on remand for a year under the alias 'Henry Shaw'. Burke and Casey were accused - correctly in Burke's case - of organising the escape of Thomas Kelly and Timothy Deasy, as they were being transferred to Belle Vue Gaol, Manchester. One of the armed Fenian group who attacked the prison carriage, Peter Rice, fired through the lock. The police sergeant inside, Charles Brett, took the bullet in the eye and was killed.[3] Burke had bought or ordered hundreds of guns and huge quantities of percussion caps in Birmingham in 1865. Witnesses said he joined Fenian meetings in Liverpool, Manchester and other cities, during which plans were made to raid the armoury at Chester Castle on 11 February 1867 (about 2000 rifles purchased by him had been stored in Liverpool[3]). While he was on remand at Clerkenwell Prison, London, on 13 December 1867, Fenians used gunpowder to blow up the wall of the exercise yard for Burke's escape; this was their second attempt. The plan was executed by Jeremiah O'Sullivan, who was part of a London-based I.R.B. group set up by Burke, and who had managed to exchange notes with him in gaol; the signal for the imminent detonation was a white rubber ball thrown over the wall. At the first signal, Burke was seen to move away from the wall and inspect his shoe. The bomb's fuse failed; a prison warder picked up the ball for his children. Information from Ireland that had already been received by the police of an attempted rescue for Burke was passed on, so police patrols were increased and the prison governor confined prisoners to cells.[12] A second attempt the following day worked, but with an empty exercise yard. The huge blast destroyed an eighteen-metre section of the wall. Twelve local people were killed, up to one hundred and twenty injured and homes and shops on Corporation Row were devastated. Working-class sympathy in England for the Fenian cause was dealt a significant blow: London resident, Karl Marx, and political activist, Charles Bradlaugh, were scornful, with Marx writing that the atrocity was a gift to the British rulers against Irish emancipation. Of six people charged at the Old Bailey on 20 April 1868, only Michael Barrett was found guilty (on 27 April): he was a Fenian transported from Scotland whose name had been provided under interrogation by one of the accused and whose identity was confirmed by a young boy. On 26 May, he became the last person publicly executed in England, having eloquently protested his innocence.[13][14][3][5][15][16][17][18][19][20]

Burke, Casey, and Mullady were charged with treason-felony at the Old Bailey because of the escape of Kelly and testimony from arms merchants and informers about weapons purchases and reports of their involvement at Fenian meetings. Burke was sentenced to fifteen years in prison and Mullady seven years; Casey was acquitted.[16] Prison conditions were typically poor. While in prison, Burke was spoken of in the House of Commons as effectively being on a slow-starvation diet which had driven him mad. In a self-diagnosis, Burke said he was being poisoned with a compound of mercury administered by the prison doctor, Dr. Steele. He was removed from Chatham prison to Woking Prison (for invalided male convicts) and thence to the new Broadmoor Criminal Lunatic Asylum, from where he was released in 1871 due to illness. [Devoy, who was in Chatham prison with Burke, claimed that the attempt at poisoning was true, saying a sample of Burke's stomach contents had been surreptitiously smuggled out for chemical analysis but that Burke had feigned insanity.] A weakened Burke went to his brother's home in County Cork to recuperate.[17][21][3][22]

Later life

In 1874, Burke returned to the U.S.[3] Public records in Chicago describe Burke as a 'public official' during the 1880s and 1890s. From the mid 1870s, he was a clerk at the War Department in Washington D.C. He lectured on Irish nationalism when he could,[23] and he campaigned for the Republicans, including at Fort Wayne, Indiana, where he stayed for some time in rooms. He was charged with associating with a prostitute in October 1880. The highly supportive Fort Wayne Daily Gazette described the charge as "preposterous" and engineered by Democrats. He was acquitted.[24] [25] He decided to settle in Fort Wayne, having met Nora Sheehy (a Democrat), a local woman and his wife-to-be. [26] After campaigning, he returned to his job in Washington D.C.[27][9]

In 1881, he left his Washington job to work on railways in Mexico. He was joined by the new Mrs. Burke in November that year and they settled in Monterrey.[28] [29]

The Fort Wayne Weekly Sentinel, referred to Burke over a few years as someone who "styles himself Colonel" and an "alleged Colonel", usually printing the rank in inverted commas (29 September 1880, 13 October 1880, 20 October 1880 and 3 November 1880). On 14 February 1883, in addition to a few compliments, Burke's life is described as a "racket" with the rank "colonel" gained from a Fenian attack on Canada and even the title "general" taken from his alleged activities in Chile. It described his hurried escape back to Fort Wayne from creditors in Mexico, having frittered local funding on a lavish new hotel in Monterrey, where he entertained Americans and Europeans with frequent parties and enjoyed an extravagant lifestyle.[30] The Gazette, however, continued its praise, calling him a "brilliant Irishman" about to be interviewed by the Chicago Tribune. [31]

Burke continued his support for the Fenian cause, even with the schisms on both sides of the Atlantic. In January 1888, Burke's friend, Dr. Patrick Cronin, disappeared and he suspected foul play at the hands of 'the triangle', a presumptuous cabal of Clan na Gael (the successor to the Fenian Brotherhood) in Chicago made up of Alexander Sullivan supported by Michael Boland and Denis Feely. Cronin - whose faction in Clan na Gael Burke supported, and who had accused Sullivan's triangle of stealing hardship money for Fenian activists - was found murdered in a sewer in May 1889. In the public outrage, Clan na Gael was permanently damaged.[32] [33][34] As late as 1911, he was still involved in purchasing large quantities of weaponry for distribution amongst Fenians in the U.S. In 1912, aged 74, he was recorded as an 'assistant engineer' in the rivers and harbour section of the Department of Public Works for Chicago.[9][35] In September 1913, he suffered a stroke with a poor prognosis. At the same time, his son, Ricard Jr., had tuberculosis (to which he succumbed).[36][37] A further stroke paralysed him and he was bedridden for five-and-a-half years.[3] On 12 July 1919, the future Irish president, Éamon de Valera, visited Burke briefly during his glad-handing tour of Chicago.[38]

Death

He died on 11 May 1922. He is buried in Mount Olivet Cemetery, Chicago.[3]

Accounts

Presentations of Burke's life are often contradictory with embroidered or untrue elements: in his lifetime, he was accused of authoring much of the embellishment.[1][30] His friend and fellow Fenian, John Devoy, said the story of his life "reads more like a romance than a record of actual facts" and related his ability to charm his hosts. For example, various accounts refer to him reaching the rank of brevet colonel for the Union, and he used the title, even though he was demustered as a captain.[7][3] It has been said he helped John Philip Holland build a submarine: Fenians provided funds but - after an internal financial dispute - stole the craft, which they were incapable of operating thereafter.[2][39] He has also been described as a "burly six-footer" when his height is evident in a 1906 photograph in which he is well short of six-feet-four Robert R. McCormick.[2][40][41]

References

- Rutherford, John (1877). The Secret History of the Fenian Conspiracy: Its Origin, Objects, & Ramifications. Vol. 1. C. K. Paul & Company. p. 152.

- "Soldier, Fenian, and patriot: Recounting the life Cork's Ricard O'Sullivan Burke". www.irishexaminer.com. 27 April 2018. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

- Devoy, John (1929). Recollections of an Irish Rebel (PDF) (1 ed.). Dublin: Irish Academic Press. Retrieved 30 August 2019.

- "The West Cork soldier who survived being 'poisoned' by a prison doctor". www.southernstar.ie. Retrieved 30 August 2019.

- "Remembering the Past: Remarkable Fenian". www.anphoblacht.com. Retrieved 30 August 2019.

- "FIELD AND STAFF, 15th REGIMENT, N.Y.S.V." (PDF). dmna.ny.gov. Retrieved 30 August 2019.

- "FIFTEENTH ENGINEERS" (PDF). dmna.ny.gov. Retrieved 30 August 2019.

- "Fifteenth New York Infantry". civilwarindex.com. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

- "Richard O'Sullivan Burke Papers". explore.chicagocollections.org. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

- Devoy, John (1929). Recollections of an Irish Rebel (PDF) (1 ed.). Dublin: Irish Academic Press. p. 235. Retrieved 30 August 2019.

- "Union Rebels: The Erin's Hope– Fenian Gunrunning by Civil War Veterans". irishamericancivilwar.com. 30 January 2016. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- "FENIANISM—THE ATTACK ON CLERKENWELL PRISON.—QUESTION". api.parliament.uk. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

- "The Fenians, the Metropolitan Police, and the Clerkenwell Explosion". victoriandetectives.com. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

- Jenkins, Brian (2008). The Fenian Problem: Insurgency and Terrorism in a Liberal State, 1858-1874. McGill-Queen's University Press. pp. 148–149.

- "THE FENIAN PRISONERS, BURKE, CASEY AND SHAW". The Brecon County Times, Neath Gazette and General Advertiser for the Counties of Brecon, Carmarthen, Radnor, Monmouth, Glamorgan, Cardigan, Montgomery, Hereford. 27 February 1868. Retrieved 29 August 2019.

- "The Fenian Conspiracy". The Illustrated London News & Sketch Limited. Vol. 52. London. 4 January 1868. p. 18. Retrieved 29 August 2019.

- "GEORGE BERRY, JOSEPH THEOBALD CASEY, HENRY SHAW". www.oldbaileyonline.org. Retrieved 29 August 2019.

- "Ricard O'Sullivan Burke (1838 - 1922)". feniangraves.net. Retrieved 28 August 2019.

- O'Brien, Gillian (2015). Blood Runs Green: The Murder That Transfixed Gilded Age Chicago. University of Chicago Press. p. 21.

- "Irish Terrorism in the Atlantic Community, 1865-1922 (The Palgrave Macmillan Transnational History Series)". epdf.pub. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

- "American citizens prisoners in Great Britain : extract from proceedings of the Ninth General Convention of the Fenian Brotherhood, held August 30th to September 5th, 1870, inclusive, in the city of New York". cuislandora.wrlc.org. pp. 11–13. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- "GEORGE BERRY, JOSEPH THEOBALD CASEY, HENRY SHAW". www.oldbaileyonline.org. Retrieved 29 August 2019.

- "Colonel Ricard O'Sullivan Burke". The San Antonio Light. San Antonio. 7 April 1883. p. 2.

- "THE COLONEL AND THE COOK". Fort Wayne Daily Gazette. Fort Wayne. 19 October 1880. p. 4. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

- "ACQUITTED". Fort Wayne Daily Gazette. Fort Wayne. 20 October 1880. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

- "PERSONAL". Fort Wayne Daily Gazette. Fort Wayne. 27 October 1880. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

- "RESUME OF THE WEEK". Fort Wayne Daily Gazette. Fort Wayne. 7 November 1880. p. 5. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

- "CITY NEWS". Fort Wayne Daily Gazette. Fort Wayne. 27 August 1881. p. 5. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

- "PERSONAL". Fort Wayne Daily Gazette. Fort Wayne. 22 November 1880. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

- "R. O'Sullivan Burke". Fort Wayne Weekly Sentinel. Fort Wayne. 14 February 1883. p. 7. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

- "CITY PERSONALS". Fort Wayne Weekly Gazette. 15 August 1883. p. 7. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

- Kenna, Shane (2013). War in the Shadows: The Irish-American Fenians who bombed Victorian Britain. Dublin: Merrion Press.

- "The Wahpeton times. [volume] (Wahpeton, Richland County, Dakota [N.D.]) 1879-1919, July 11, 1889, Image 4". 11 July 1889.

- "NEWS IN BRIEF". The Wahpeton times. 11 July 1889. p. 4. Retrieved 10 September 2019.

- "Annual Report of the Department of Public Works for the Year Ending December 31, 1912 to the City Council of the City of Chicago". City Council of the City of Chicago. 1912. p. 263. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

- "Letter from Ricard O'Sullivan Burke to James Reidy regarding arms needed for Cleveland, Kansas City and Western points including Chicago". catalogue.nli.ie. Retrieved 10 September 2019.

- "Letter from John T. Keating to John Devoy saying that Ricard O'Sullivan Burke is ill and prognosis for recovery is not good". catalogue.nli.ie. Retrieved 10 September 2019.

- Hannigan, Dave (2012). De Valera in America: The Rebel President's 1919 Campaign. Dublin: The O'Brien Press. ISBN 9781847175090. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

- "John Philip Holland: The Father of the Modern Submarine". interestingengineering.com. 19 August 2017. Retrieved 4 September 2019.

- "River inspection trip, Richard O'Sullivan Burke, ex-mayor Edward F. Dunne, Col. Robt. R. McCormick, and Jos. M. Patterson and an unidentified man standing on a boat on the Chicago River". explore.chicagocollections.org. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

- "Debates Swirled About McCormick". archive.nytimes.com. Retrieved 9 September 2019.