Patrick Henry Cronin

Philip Patrick Henry Cronin (August 7, 1846 – May 4, 1889) was an Irish immigrant to the United States, a physician, and a member of Clan na Gael in Chicago. In 1889, Cronin was murdered by affiliates of Clan na Gael. Following an extensive investigation into his death, the murder trial was, at the time, the longest-running trial in U.S. history.[2] Cronin's murder caused a public backlash against secret societies, including protests and written condemnations by the leadership of the Catholic Church.

Patrick Henry Cronin | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Cronin, drawn from a photograph taken shortly before his murder | |

| Born | Philip Patrick Henry Cronin[1] August 7, 1846 |

| Disappeared | May 4, 1889 (aged 42) |

| Died | Chicago, Illinois |

| Cause of death | Murder |

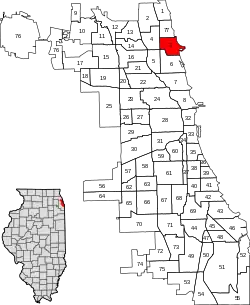

| Body discovered | Lakeview, Chicago |

| Resting place | Calvary Cemetery, Evanston, Illinois |

| Nationality | Irish |

| Citizenship | American |

| Education | Missouri Medical College, Saint Louis University (Masters, PhD.) |

| Occupation | Physician |

Cronin grew up in the U.S. and Canada, and moved to the Midwestern United States after the American Civil War. He became a physician and a prominent member of high society, and represented St. Louis at the Exposition Universelle (1878). While in St. Louis, Cronin joined multiple clubs, among them, the Irish nationalist organization, Clan na Gael. When he moved to Chicago, Cronin continued his involvement with Clan na Gael. After criticizing the leadership of the Chicago camp of Clan na Gael, he was expelled from the group and accused of being a British spy. In May 1889, Cronin disappeared. Later that month, public works employees discovered his body in a sewer in a northern suburb of Chicago. The press coverage of the investigation and trial caught international attention.[3] Cronin's funeral drew the largest crowds for a funeral since the arrival of Abraham Lincoln's body in Chicago. Patrick O'Sullivan, Daniel Coughlin, Martin Burke, and John Kunzel were found guilty of the murder of Patrick Cronin.

Early life

Born on August 7, 1846, in Buttevant, County Cork, Ireland,[4] Cronin was an infant when his family relocated to New York City. Thereafter, they moved to Baltimore, and later to Ontario. At the age of 10, he was enrolled at the Academy of St. Catherine's, graduating with honors in 1863. For the next few years, he worked in Pennsylvania as a school teacher. In 1867, he moved west to Missouri, eventually settling in St. Louis.[5]

Career

Cronin was known for his tenor singing voice. He sang at Irish events, at his local Catholic church, and at the Second Baptist Church in St. Louis, which was unusual because Cronin was Catholic. His singing gained the attention of affluent businessmen in St. Louis. After working for the St. Louis and Southeastern Railroad as a city ticket agent, Cronin secured sponsorship from the Bagnal Timber Company to study at Missouri Medical College. He graduated in the late 1870s and continued his education at Saint Louis University, where he earned a Master's degree and a Doctor of Philosophy. Cronin was involved with the revival of the St. Louis College of Physicians and Surgeons, and he served as its professor of eye and ear diseases by the early 1880s. Cronin was also well known in St. Louis society and attended the Exposition Universelle (1878) in Paris as one of Missouri's state commissioners.[6]

Through his involvement with Clan na Gael, Cronin secured a position with Cook County Hospital. Cronin did not remain with Cook County Hospital, instead opting to open a private medical practice. He had two offices, one downtown and the other at his residence on North Clark Street, where he lived with Theo and Cordelia Conklin. In Chicago, Cronin sang at Holy Name Cathedral and at Irish events in the city.[6]

Involvement with Clan na Gael

Cronin was a member of secret societies Royal Arcanum and Chosen Friends,[7] as well as multiple Irish societies, including the Ancient Order of Hibernians and, starting in late 1876, Clan na Gael.[6] Clan na Gael was an oath bound secret society of Fenians devoted to Irish independence from the British Empire. The organization engaged in large amounts of fundraising, but under the leadership of Alexander Sullivan, the Clan took a more paramilitary role in the fight for Irish independence.[4] By the early 1880s, Cronin had determined that in order to gain a more prominent position within Clan na Gael, he needed to be near Sullivan and to move to Chicago.[6] In Chicago, Cronin was also a member of The Foresters and The Royal League.[8]

Rivalry with Alexander Sullivan

.jpg.webp)

Cronin sought to rise through the ranks of the Chicago camp of Clan na Gael, which brought him in contact with the Triangle.[9] Clan na Gael was administered by chapters called "camps," and Camp 20 (in Chicago) was Clan na Gael's headquarters.[8] By 1884, the Clan was controlled by Alexander Sullivan, with support from Michael Boland and Denis Feely. This triumvirate was referred to as "the Triangle," and the symbol was used to indicate them in memoranda and circulars.[10] Sullivan and his followers favored guerrilla warfare on British soil. This policy became referred to as the "dynamite policy". The "dynamite policy" or "Dynamite War" consisted largely of terrorist attacks on public spaces in Great Britain,[8] including the 1885 bombing of the Tower of London and House of Commons.[11] Due to Henri le Caron, a British Intelligence mole inside Clan na Gael, the dynamite campaign was unsuccessful, resulting in the deaths and arrests of the men attempting to bomb British targets. Meanwhile, Cronin emerged as the leader of the opposition, making him Sullivan's rival. Cronin accused Sullivan of embezzlement, and demanded that Sullivan account for the missing funds. In retaliation, Sullivan accused Cronin of "treason," and ordered an internal trial with a panel of five men to try Cronin. Among the panel members were Detective Daniel Coughlin of the Chicago Police Department, and Henri le Caron. In 1885, the panel found Cronin guilty and expelled him from Clan na Gael. Instead, the decision to expel Cronin split Clan na Gael, with many Chicago members supporting Cronin.[9] Thousands of members quit Clan na Gael and formed Pro-Cronin camps.[7]

This personal feud culminated in 1888,[4] when Cronin publicly accused Sullivan of embezzling $100,000 from Clan na Gael's pension fund for the families of deceased and incarcerated "dynamiters."[9] Hoping to settle the feud and bring Clan members back together, leaders of both factions agreed to an internal investigation.[8] Clan na Gael members organized an internal trial, held in New York City, to investigate the charges against Sullivan. The trial continued for five months and Sullivan was cleared but Cronin refused to acknowledge the outcome, maintaining that Sullivan was crooked.[4]

The "dynamite policy" failed in large part because of the British spy Henri le Caron, who posed as a French-Irish member of Clan na Gael. Cronin, who correctly suspected le Caron of being a spy, rallied his followers with the fact that Sullivan was close to le Caron. In response, Sullivan shared alleged British Intelligence reports that le Caron had provided and which named other spies, Cronin among them. The accusation that Cronin was a British spy put his life in danger, and Cronin was aware of his tenuous position in the spring of 1889.[4]

Disappearance

Cronin reportedly told friends that his life was in danger in the spring of 1889. Nonetheless, he agreed to act as company physician of the employees of Patrick O'Sullivan. In return for a stipend, Cronin was hired to attend to any injured employee of O'Sullivan's ice business.[9] On March 20, 1889, Martin Burke, going by the name Frank Williams,[12] rented a cottage in suburban Lake View, now the Uptown neighborhood of Chicago, one block from the offices of O'Sullivan Ice Company. Burke told his landlord that his brother and invalid sister would be moving in with him and furniture, including a large trunk, was delivered to the cottage. On May 4, Chicago Police detective Daniel Coughlin came to a Chicago stable, and told the liveryman that later, a friend of his would need a horse and buggy. Coughlin instructed the liveryman to "say nothing to anyone about it." Later that day, Coughlin's friend came to fetch a two-seat buggy and a white horse.[13]

On the night of May 4, 1889, a man called on Cronin at his home, seeking medical care for an injured worker at O'Sullivan's ice house in Lake View. Cronin was observed leaving in a buggy with a white horse. He never returned home.[7][8] Cronin's friends worried about his absence.[8] His landlords and friends reported his disappearance to the police, who assigned Daniel Coughlin to the case. Coughlin and the other officers reported searching "high and low" but found no trace of Cronin or a crime.[9] Henry M. Hunt reported that Theo Conklin did some investigating, and drove to Lake View to question O'Sullivan about the accident call. O'Sullivan was confused by the inquiry, and replied that all of his employees were in good health, and none of them called for the doctor.[14] The Conklins also found that Cronin did not take his revolver with him, as he would have for a long trip, and that he only carried a small amount of money.[14]

On May 9, Annie Murphy, an elocutionist who, like Cronin, was well known in Irish and Catholic circles, reported that she saw Cronin on a streetcar on Clark Street just after 9 p.m. on May 4. Her father, Thomas Murphy, was an officer at a local Clan na Gael camp. The conductor of the street car corroborated Annie Murphy's claim.[15] On May 10, Charles T. Long, the son of a prominent newspaper publisher in Toronto who belonged to a secret society with Cronin, sent dispatches to Chicago's morning papers that Cronin was alive and well in Canada. Long described Cronin as seeming to be "slightly deranged."[16] The accounts of Cronin in Canada were definitive enough evidence for Cronin's enemies that he was guilty of some crime and had fled Chicago to escape justice.[17] Some reports said Cronin admitted to being a British spy, and was making his way to England.[7] Other rumors circulated by the press were that Cronin was fleeing prosecution for performing an abortion, or he was avoiding the consequences of a romantic affair.[9]

Investigation

The trunk

Around 2 a.m. on May 5, two Lake View police officers witnessed a carpenter's wagon carrying a large trunk speeding north on Clark Street. At 3:30 a.m., the wagon returned, passing the intersection of Clark St. and Diversey Parkway, this time without the trunk. The officers stopped the wagon, but found nothing suspicious, and let the two men driving it continue on their way.[18] The following morning, police were called to a ditch on Evanston Avenue, where passersby found a large trunk, filled with blood spatter and blood soaked cotton. There was also a dark brown lock of hair found inside. Lake View Police Captain Villiers examined the trunk and concluded that an adult person had been murdered and stuffed inside. The trunk itself was unremarkable, and was likely purchased for the purpose of holding a body. Villiers determined that a murder took place sometime after midnight.[19]

The body

Police searched the brush, grass, and vacant houses for a mile surrounding where the trunk was found, but discovered no trace of any body.[20] The search continued. On May 22, employees of the Board of Public Works were called to investigate a jammed sewer near Broadway and Foster Avenue,[13] and found the corpse of a man, wedged into the catch basin of the sewer.[9][8] The body was stripped bare besides a bloody towel wrapped around its neck, and an Agnus dei medallion. The coroner found five scalp wounds from a sharp, narrow weapon, possibly an ice pick.[8] His neck was broken, and he had been struck with a blunt instrument on his cheek and temple.[13] A few hours after the body was found, the Conklins identified the deceased as Cronin at the morgue of the Lake View police station.[9] Cronin's clothes, which were cut from his body, were found in November in a manhole at Broadway and Buena Avenue.[13]

Further evidence

Two days later, police identified the scene of the crime. The cottage Martin Burke (alias Frank Williams) rented in March was left vacant in May. The owners entered the cottage to find blood stains and broken furniture.[9] The floor of the cottage was recently painted yellow, an attempt to hide the blood. The furniture and the trunk came from Revel's furniture store, rented by a J. B. Simmonds. Police suspected that Simmonds was an alias for Patrick "The Fox" Cooney, a familiar of O'Sullivan and Coughlin, and an enemy of Cronin.[7] Cooney fled Chicago and was not found, but in the cotton batting found with Cronin's body, investigators found a man's severed finger. Since none of the other suspects were missing a finger, they believed it was Cooney's.[12]

The police also identified the stable, the same one Daniel Coughlin had visited, as the source of the white horse and buggy that took Cronin from his home on May 4. The owner of the stable told Chief of Police George W. Hubbard, on the night Cronin disappeared, a man named "Smith," referred by Detective Coughlin, rented a white horse and buggy.[9] Police identified the man who drove the carriage as John Kunze, a friend of Coughlin's.[7] Police arrested Frank Woodruff when he attempted to sell the horse and buggy to a stable owner, who informed police of the suspicious sale. Woodruff confessed to being hired to transport a trunk around 2 a.m., but claimed that a nervous Cronin helped haul into Woodruff's buggy a trunk with a mutilated body of a woman inside.[21]

Funeral

_at_Calvary_Cemetery%252C_Evanston.jpg.webp)

Cronin's funeral was the most attended since Abraham Lincoln's body arrived in Chicago.[22] On Saturday, May 25, 1889, nearly 12,000 people visited Cavalry Armory on Michigan Avenue to see Cronin's coffin.[23] The body was too decomposed and damaged to permit an open casket. On Sunday morning, May 26, the funeral procession made its way through the streets of Chicago. Cronin's casket was placed in a hearse and joined a procession of 8,000 people.[23] The procession moved north on Michigan Avenue to Rush Street, to Chicago Avenue, to State Street, to Holy Name Cathedral for the funeral mass.[24] Thousands of people gathered in the streets during the mass, waiting for the ceremony to end. Cronin's casket travelled to the funeral by train to Calvary Cemetery. Five thousand people gathered at the cemetery for the entombment.[25] Cronin was celebrated as an Irish American hero and a martyr.[26]

Arrests

On May 25, the Chicago Times reported that Daniel Coughlin had hired the horse and buggy used to abduct Cronin. Coughlin was interrogated by a panel that included Police Chief Hubbard and Chicago Mayor DeWitt Clinton Cregier. After giving "evasive and vague" answers, Coughlin was arrested as an accomplice to the abduction and murder of Cronin.[27] On the morning of May 27, Patrick O'Sullivan, the ice man, was called to the Lake View Police Station and was arrested upon arrival.[28] After much questioning, O'Sullivan confessed that he had known Coughlin for years, he had contrived his introduction to Cronin as a physician, he was a member of Clan na Gael, and he had talked with "Frank Williams," who rented the cottage where Cronin was murdered. O'Sullivan and Coughlin were held at Cook County Jail.[29] In June, Martin Burke (Frank Williams), was found travelling under another alias in Winnipeg, on his way to Liverpool. On June 11, Chicago police arrested Alexander Sullivan, but only held him for one night on account of the lack of evidence of his involvement.[9] Frank Woodruff and John Beggs, members of Clan na Gael Camp 20, were also arrested in June for their involvement in Cronin's murder.[8]

Press

According to Henry M. Hunt, the murder of Cronin ranked in national importance with the assassinations of Abraham Lincoln and James A. Garfield, as the gruesome crime was an international sensation.[30] The press were involved in the case from the earliest days. The newspaper offices in Chicago were notified of Cronin's disappearance promptly on May 5, and "sleuth reporters" were investigating by sundown.[31] The Chicago Times reporting that Daniel Coughlin was involved led to long-awaited arrests.[27] From May to December 1889, thousands of newspaper stories and editorials documented and speculated about the Cronin case.[9] According to Gillian O'Brien, Chicago journalists used "combination reporting," collaborating and sharing information to produce more detailed reports on the Cronin case.[32] Journalists scrutinized the police, and shed light on irregular practices, holding the police accountable.[33]

Newspapers in Ireland paid much less attention to Cronin's murder, and reported that it was the actions of individuals, not a larger conspiracy.[34] American journalists, however, treated the case as a sensational murder mystery, sometimes embellishing reports to attract higher readership. The press was quick to condemn the alleged murders, Alexander Sullivan among them.[35]

Newspapers continued to run stories about Cronin's murder until the 1950s. In 1929, for the fortieth anniversary of Cronin's death, the Chicago Tribune ran a contest in which readers asked to "solve the mystery of the case" for a $500 prize.[36]

Trial

The public was so steeped in press coverage of the Cronin case, it was very difficult to find jurors who had not already formed an opinion of the case.[9] Jury selection began on August 26, 1889, and continued through October 22. 1,115 men were interviewed, making this (at the time) the largest and longest jury selection process in American history.[37] The trial began on October 23, 1889, and 5,000 people came to the courthouse (of which only 200 could fit in the courtroom).[9] Over the following seven weeks of the trial, the defense and prosecution called 190 witnesses.[38] At the time, it was the longest-running trial in American history.[3]

During the trial, the prosecution focused on the actions of Beggs, O'Sullivan, and Coughlin. Kunze was seen as a secondary player, not as guilty as the other men.[39] Many witnesses, as well as the defendants, admitted to their involvement with Clan na Gael.[40] Some witnesses called testified that Cronin believed his life was in danger, others testified that they had been asked to harm or kill Cronin.[41] There was an attempt to bribe the jury but the juror Charles C. Dix turned over the evidence to State's Attorney Joel Longnecker.[42]

Closing arguments took place from November 29 to December 12, 1889.[42] Then, jurors deliberated to determine whether or not each defendant was guilty, and what the sentence would be for those found guilty (with a minimum sentence of 14 years in prison).[43] The jurors deliberated for 70 hours before issuing verdicts.[7] Seven men were indicted for Cronin's murder, and four—Patrick O'Sullivan, Dan Coughlin, Martin Burke, and John Kunzel—were found guilty and sentenced to prison time. Kunze served three years in prison but claimed innocence throughout.[13] He was granted a new trial, and subsequently acquitted.[7] Coughlin was acquitted at a second trial,[13] likely because the jury was bribed. O'Sullivan and Burke died in prison in 1892.[9] John Beggs was found not guilty.[8] Patrick Cooney, who rented the cottage as J.B. Simmonds, fled the country, and was never found.[13]

Backlash against secret societies

As Cronin was murdered after exposing corruption in Clan na Gael, the Clan became associated with murderous plot.[9] The Catholic Church mobilized against Clan na Gael. Archbishop Patrick A. Feehan faced significant pressure from the press, some Clan camps, and members of the church, to condemn the Clan and the parties involved in Cronin's death. Feehan produced a long report about "the criminal acts of Clan na Gael" for Cardinal Giovanni Simeoni. Pope Leo XIII subsequently granted Archbishop Feehan all means necessary to declare that Clan na Gael was in opposition to the Church.[44]

The public organized against secret societies as well. Thousands of Chicagoans attended protest meetings and concerts to push for the suppression of secret societies.[45] According to Gillian O'Brien, by the time "the Cronin murder case had concluded, there was little that remained secret about the secret society [Clan na Gael]."[46]

References

Citations

- Hunt, pp. 17.

- Gillian, O'Brien (March 9, 2015). Blood runs green : the murder that transfixed gilded age Chicago. Chicago. ISBN 9780226248950. OCLC 883304944.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - "The Irish Republican Murder that Shocked Chicago". Chicago Tonight | WTTW. Retrieved August 4, 2017.

- "How the English spy who sought to destroy Parnell tore Irish America apart". The Irish Times. Retrieved August 30, 2017.

- Hunt, Henry M. (1889). The crime of the century; or, The assassination of Dr. Patrick Henry Cronin. A complete and authentic history of the greatest of modern conspiracies. University of California Libraries. Chicago : H. L. & D. H. Kochersperger. pp. 23–24.

- O'Brien, pp. 18-19.

- "The mysterious 19th century murder of Dr Patrick Henry Cronin". IrishCentral.com. June 13, 2016. Retrieved August 22, 2017.

- "Clan-na-Gael and the Murder of Dr. Cronin". www.murderbygaslight.com. Retrieved August 22, 2017.

- "'A diabolical murder': Clan na Gael, Chicago and the murder of Dr Cronin - History Ireland". History Ireland. April 27, 2015. Retrieved August 29, 2017.

- O'Brien, pp. 35-36.

- Dumke, Mick. "A 19th-century Chicago murder case raises questions about the criminal justice system—then and now". Chicago Reader. Retrieved August 29, 2017.

- O'Brien, pp. 120-121.

- "A Bloody Step On The Road To Irish Freedom". tribunedigital-chicagotribune. Retrieved August 30, 2017.

- Hunt, pp. 28-29.

- Hunt, pp. 102-104.

- Hunt, pp. 108.

- Hunt, pp. 117-118.

- Hunt, pp. 31-33.

- Hunt, pp. 33-35.

- Hunt, pp. 36-37.

- Hunt, pp. 49-50.

- O'Brien, pp. 1.

- Hunt, pp. 224.

- Hunt, pp. 226.

- Hunt, pp. 233.

- Hunt, pp. 234.

- O'Brien, pp. 109-110.

- Hunt, pp. 217.

- Hunt, pp. 218.

- Hunt, pp. 15-16.

- Hunt, pp. 31.

- O'Brien, pp. 132-133.

- O'Brien, pp. 194.

- O'Brien, pp. 137.

- O'Brien, pp. 139.

- O'Brien, pp. 213.

- O'Brien, pp. 163.

- O'Brien, pp. 171.

- O'Brien, pp. 174.

- O'Brien, pp. 112.

- O'Brien, pp. 175.

- O'Brien, pp. 180.

- O'Brien, pp. 182.

- O'Brien, pp. 118.

- O'Brien, pp. 126.

- O'Brien, pp. 195.

Sources

- O'Brien, Gillian. Blood Runs Green: the Murder That Transfixed Gilded Age Chicago. The University of Chicago Press, 2016.

- Hunt, Henry M. The Crime of the Century; or, The Assassination of Dr. Patrick Henry Cronin. A complete and authentic history of the greatest of modern conspiracies. University of California Libraries. Chicago : H.L. & D. H. Kochersperger, 1889.

Further reading

- McEnnis, John T., The Clan-Na-Gael and the Murder of Dr. Cronin. San Francisco: G. P. Woodward, 1889.

External links

Media related to Patrick Henry Cronin at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Patrick Henry Cronin at Wikimedia Commons