Rheometer

A rheometer is a laboratory device used to measure the way in which a viscous fluid (a liquid, suspension or slurry) flows in response to applied forces. It is used for those fluids which cannot be defined by a single value of viscosity and therefore require more parameters to be set and measured than is the case for a viscometer. It measures the rheology of the fluid.

| Part of a series on |

| Continuum mechanics |

|---|

There are two distinctively different types of rheometers. Rheometers that control the applied shear stress or shear strain are called rotational or shear rheometers, whereas rheometers that apply extensional stress or extensional strain are extensional rheometers. Rotational or shear type rheometers are usually designed as either a native strain-controlled instrument (control and apply a user-defined shear strain which can then measure the resulting shear stress) or a native stress-controlled instrument (control and apply a user-defined shear stress and measure the resulting shear strain).

Meanings and origin

The word rheometer comes from the Greek, and means a device for measuring main flow.[1] In the 19th century it was commonly used for devices to measure electric current, until the word was supplanted by galvanometer and ammeter. It was also used for the measurement of the flow of liquids, in medical practice (flow of blood) and in civil engineering (flow of water). This latter use persisted to the second half of the 20th century in some areas. Following the coining of the term rheology the word came to be applied to instruments for measuring the character rather than quantity of flow, and the other meanings are obsolete. (Principal Source: Oxford English Dictionary) The principle and working of rheometers is described in several texts.[2][3]

Types of shear rheometer

Shearing geometries

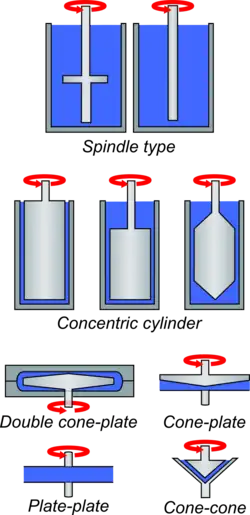

Four basic shearing planes can be defined according to their geometry,

- Couette drag plate flow

- Cylindrical flow

- Poiseuille flow in a tube and

- Plate-plate flow

The various types of shear rheometers then use one or a combination of these geometries.

Linear shear

One example of a linear shear rheometer is the Goodyear linear skin rheometer, which is used to test cosmetic cream formulations, and for medical research purposes to quantify the elastic properties of tissue. The device works by attaching a linear probe to the surface of the tissue under test, a controlled cyclical force is applied, and the resultant shear force measured using a load cell. Displacement is measured using an LVDT. Thus the basic stress–strain parameters are captured and analysed to derive the dynamic spring rate of the tissue under tests.

Pipe or capillary

Liquid is forced through a tube of constant cross-section and precisely known dimensions under conditions of laminar flow. Either the flow-rate or the pressure drop are fixed and the other measured. Knowing the dimensions, the flow-rate can be converted into a value for the shear rate and the pressure drop into a value for the shear stress. Varying the pressure or flow allows a flow curve to be determined. When a relatively small amount of fluid is available for rheometric characterization, a microfluidic rheometer with embedded pressure sensors can be used to measure pressure drop for a controlled flow rate.[4][5]

Capillary rheometers are especially advantageous for characterization of therapeutic protein solutions since it determines the ability to be syringed.[6] Additionally, there is an inverse relationship between the rheometry and solution stability, as well as thermodynamic interactions.

Dynamic shear rheometer

A dynamic shear rheometer, commonly known as DSR is used for research and development as well as for quality control in the manufacturing of a wide range of materials. Dynamic shear rheometers have been used since 1993 when Superpave was used for characterising and understanding high temperature rheological properties of asphalt binders in both the molten and solid state and is fundamental in order to formulate the chemistry and predict the end-use performance of these materials.

Rotational cylinder

The liquid is placed within the annulus of one cylinder inside another. One of the cylinders is rotated at a set speed. This determines the shear rate inside the annulus. The liquid tends to drag the other cylinder round, and the force it exerts on that cylinder (torque) is measured, which can be converted to a shear stress. One version of this is the Fann V-G Viscometer, which runs at two speeds, (300 and 600 rpm) and therefore only gives two points on the flow curve. This is sufficient to define a Bingham plastic model which was once widely used in the oil industry for determining the flow character of drilling fluids. In recent years rheometers that spin at 600, 300, 200, 100, 6 & 3 RPM have become more commonplace. This allows for more complex fluids models such as Herschel–Bulkley to be used. Some models allow the speed to be continuously increased and decreased in a programmed fashion, which allows the measurement of time-dependent properties.

Cone and plate

The liquid is placed on horizontal plate and a shallow cone placed into it. The angle between the surface of the cone and the plate is around 1–2 degrees but can vary depending on the types of tests being run. Typically the plate is rotated and the torque on the cone measured. A well-known version of this instrument is the Weissenberg rheogoniometer, in which the movement of the cone is resisted by a thin piece of metal which twists—known as a torsion bar. The known response of the torsion bar and the degree of twist give the shear stress, while the rotational speed and cone dimensions give the shear rate. In principle the Weissenberg rheogoniometer is an absolute method of measurement providing it is accurately set up. Other instruments operating on this principle may be easier to use but require calibration with a known fluid. Cone and plate rheometers can also be operated in an oscillating mode to measure elastic properties, or in combined rotational and oscillating modes.

Basic concepts of shear rheometer[7]

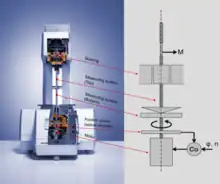

In the past, devices with controlled strain or strain rate (CR rheometers) were distinguished from rheometers with controlled stress (CS rheometers) depending on the measuring principle.

In a controlled strain (CR) rheometer, the sample is subjected to displacement or speed (strain or strain rate) using a DC motor, and the resulting torque (stress) is measured separately using an additional force-torque sensor (torque compensation transducer). The electric current used to generate the displacement or speed of the motor is not used as a measure of the torque acting in the sample. This mode of operation is also referred to as separate motor transducer mode (SMT).

- Deflection angle/strain and shear rate are set by the motor based on the position control of the optical encoder in the lower part.

- Sample reaction (the stress acting within the sample) is measured by an additional force-torque transducer (torque re-balance transducer)

- The separation of drive and torque measurement has advantages in strain-controlled tests, since the motor's moment of inertia has no influence on the measured torque.

- Limitations of the SMT mode can be found in stress-controlled measurements (e.g. creep tests)

In a controlled-stress (CS) rheometer, the torque acting in the sample is determined directly from the electrical torque generated in the motor. With such a design, no separate torque sensor is required. Usually, this mode of operation is described as combined motor-transducer mode (CMT).

- The stress acting in the sample is determined directly from the torque generated in the motor, which is required to deform the sample.

- Deflection angle/strain and shear rate are determined by the use of an optical encoder.

- Single-motor rheometers allow characterization of samples in either strain/shear rate or shear stress-controlled tests

- Since only one actor (motor) is required, the single-motor rheometer can be easily combined with additional application-specific accessories that enable the study of material properties in a variety of different applications.

- Limitations may occur from less precise data evaluation in the transient regime of start-up shear tests.

Nowadays, there are device concepts that allow both working modes, the combined motor transducer mode and the separate motor transducer mode, by using two motors in one device. The use of only one motor enables measurements to be made in the combined motor transducer mode. Using both motors allows working in the separate motor transducer mode, where one motor is used to deform the sample while the other motor is used to record the torque acting in the sample. Furthermore, this concept allows for additional modes of operation, such as counter-rotating mode, where both motors can rotate or oscillate in opposite directions. This mode of operation is used, for example, to increase the maximum achievable shear rate range or for advanced rheooptical characterization of samples.

Types of extensional rheometer

The development of extensional rheometers has proceeded more slowly than shear rheometers, due to the challenges associated with generating a homogeneous extensional flow. Firstly, interactions of the test fluid or melt with solid interfaces will result in a component of shear flow, which will compromise the results. Secondly, the strain history of all the material elements must be controlled and known. Thirdly, the strain rates and strain levels must be high enough to stretch the polymeric chains beyond their normal radius of gyration, requiring instrumentation with a large range of deformation rates and a large travel distance.[8][9]

Commercially available extensional rheometers have been segregated according to their applicability to viscosity ranges. Materials with a viscosity range from approximately 0.01 to 1 Pa.s. (most polymer solutions) are best characterized with capillary breakup rheometers, opposed jet devices, or contraction flow systems. Materials with a viscosity range from approximately 1 to 1000 Pa.s. are used in filament stretching rheometers. Materials with a high viscosity >1000 Pa.s., such as polymer melts, are best characterized by constant-length devices.[10]

Extensional rheometry is commonly performed on materials that are subjected to a tensile deformation. This type of deformation can occur during processing, such as injection molding, fiber spinning, extrusion, blow-molding, and coating flows. It can also occur during use, such as decohesion of adhesives, pumping of hand soaps, and handling of liquid food products.

A list of currently and previously marketed commercially available extensional rheometers is shown in the table below.

Commercially available extensional rheometers

| Instrument name | Viscosity Range [Pa.s] | Flow Type | Manufacturer | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Currently marketed | Rheotens | >100 | Fiber spinning | Goettfert |

| CaBER | 0.01-10 | Capillary breakup | Thermo Scientific | |

| Sentmanat extensional rheometer | >10000 | Constant length | Xpansion Instruments | |

| FiSER | 1–1000 | Filament stretching | Cambridge Polymer Group | |

| VADER | >100 | Controlled Filament stretching | Rheo Filament | |

| Previously marketed | RFX | 0.01-1 | Opposed Jet | Rheometric Scientific |

| RME | >10000 | Constant length | Rheometric Scientific | |

| MXR2 | >10000 | Constant length | Magna Projects |

Rheotens

Rheotens is a fiber spinning rheometer, suitable for polymeric melts. The material is pumped from an upstream tube, and a set of wheels elongates the strand. A force transducer mounted on one of the wheels measures the resultant extensional force. Because of the pre-shear induced as the fluid is transported through the upstream tube, a true extensional viscosity is difficult to obtain. However, the Rheotens is useful to compare the extensional flow properties of a homologous set of materials.

CaBER

The CaBER is a capillary breakup rheometer. A small quantity of material is placed between plates, which are rapidly stretched to a fixed level of strain. The midpoint diameter is monitored as a function of time as the fluid filament necks and breaks up under the combined forces of surface tension, gravity, and viscoelasticity. The extensional viscosity can be extracted from the data as a function of strain and strain rate. This system is useful for low viscosity fluids, inks, paints, adhesives, and biological fluids.

FiSER

The FiSER (filament stretching extensional rheometer) is based on the works by Sridhar et al. and Anna et al.[11] In this instrument, a set of linear motors drive a fluid filament apart at an exponentially increasing velocity while measuring force and diameter as a function of time and position. By deforming at an exponentially increasing rate, a constant strain rate can be achieved in the samples (barring endplate flow limitations). This system can monitor the strain-dependent extensional viscosity, as well as stress decay following flow cessation. A detailed presentation on the various uses of filament stretching rheometry can be found on the MIT web site.[12]

Sentmanat

The Sentmanat extensional rheometer (SER) is actually a fixture that can be field installed on shear rheometers. A film of polymer is wound on two rotating drums, which apply constant or variable strain rate extensional deformation on the polymer film. The stress is determined from the torque exerted by the drums.

Acoustic rheometer

Acoustic rheometers employ a piezo-electric crystal that can easily launch a successive wave of extensions and contractions into the fluid. This non-contact method applies an oscillating extensional stress. Acoustic rheometers measure the sound speed and attenuation of ultrasound for a set of frequencies in the megahertz range. Sound speed is a measure of system elasticity. It can be converted into fluid compressibility. Attenuation is a measure of viscous properties. It can be converted into viscous longitudinal modulus. In the case of a Newtonian liquid, attenuation yields information on the volume viscosity. This type of rheometer works at much higher frequencies than others. It is suitable for studying effects with much shorter relaxation times than any other rheometer.

Falling plate

A simpler version of the filament stretching rheometer, the falling plate rheometer sandwiches liquid between two solid surfaces. The top plate is fixed, and bottom plate falls under the influence of gravity, drawing out a string of the liquid.

Capillary/contraction flow

Other systems involve liquid going through an orifice, expanding from a capillary, or sucked up from a surface into a column by a vacuum. A pressurized capillary rheometer can be used to design thermal treatments of fluid food. This instrumentation could help prevent over and under-processing of fluid food because extrapolation to high temperatures would not be necessary.[13]

See also

References

- Mezger, Thomas (2014). Applied Rheology (6th ed.). Austria: Anton Paar. p. 192. ISBN 9783950401608.

- Macosko, Christopher W. (1994). Rheology: Principles, Measurements, and Applications. Wiley-VCH. ISBN 0-471-18575-2.

- Ferry, JD (1980). Viscoelastic Properties of Polymers. Wiley. ISBN 0-471-04894-1.

- Pipe, CJ; Majmudar, TS; McKinley, GH (2008). "High Shear-Rate Viscometry". Rheologica Acta. 47 (5–6): 621–642. doi:10.1007/s00397-008-0268-1. S2CID 16953617.

- Chevalier, J; Ayela, F. (2008). "Microfluidic on chip viscometers". Rev. Sci. Instrum. 79 (7): 076102. Bibcode:2008RScI...79g6102C. doi:10.1063/1.2940219. PMID 18681739.

- Hudson, Steven (10 October 2014). "A Microliter Capillary Rheometer for the Characterization of Protein Solutions". Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 104 (2): 678–685. doi:10.1002/jps.24201. PMID 25308758.

- Mezger, Thomas G. (2020). The Rheology Handbook (5th Revised ed.). Hanover: Vincentz Network GmbH & Co. KG, Hanover. pp. 400–403. ISBN 978-3-86630-532-8.

- Macosko, Christopher W. (1994). Rheology : principles, measurements, and applications. New York: VCH. ISBN 1-56081-579-5.

- Barnes, Howard A. (2000). A handbook of elementary rheology. Aberystwyth: Univ. of Wales, Institute of Non-Newtonian Fluid Mechanics. ISBN 0-9538032-0-1.

- Springer Handbook of Experimental Fluid Mechanics, Tropea, Foss, Yarin (eds), Chapter 9.1(2007)

- Sridhar, J. Non-Newtonian Fluid Mech., vol 40, 271–280 (1991); Anna, J. Non-Newtonian Fluid Mech., vol 87, 307–335 (1999)

- McKinley, G. "A decade of filament stretching rheometry". web.mit.edu.

- Ros-Polski, Valquíria (5 March 2014). "Rheological Analysis of Sucrose Solution at High Temperatures Using a Microwave-HeatedPressurized Capillary Rheometer". Food Science. 79 (4): E540–E545. doi:10.1111/1750-3841.12398. PMID 24597707.

- K. Walters (1975) Rheometry (Chapman & Hall) ISBN 0-412-12090-9

- A.S.Dukhin and P.J.Goetz "Ultrasound for characterizing colloids", Elsevier, (2002)