Requirements analysis

In systems engineering and software engineering, requirements analysis focuses on the tasks that determine the needs or conditions to meet the new or altered product or project, taking account of the possibly conflicting requirements of the various stakeholders, analyzing, documenting, validating and managing software or system requirements.[2]

| Part of a series on |

| Software development |

|---|

Requirements analysis is critical to the success or failure of a systems or software project.[3] The requirements should be documented, actionable, measurable, testable,[4] traceable,[4] related to identified business needs or opportunities, and defined to a level of detail sufficient for system design.

Overview

Conceptually, requirements analysis includes three types of activities:

- Eliciting requirements: (e.g. the project charter or definition), business process documentation, and stakeholder interviews. This is sometimes also called requirements gathering or requirements discovery.

- Recording requirements: Requirements may be documented in various forms, usually including a summary list and may include natural-language documents, use cases, user stories, process specifications and a variety of models including data models.

- Analyzing requirements: determining whether the stated requirements are clear, complete, unduplicated, concise, valid, consistent and unambiguous, and resolving any apparent conflicts. Analyzing can also include sizing requirements.

Requirements analysis can be a long and tiring process during which many delicate psychological skills are involved. New systems change the environment and relationships between people, so it is important to identify all the stakeholders, take into account all their needs and ensure they understand the implications of the new systems. Analysts can employ several techniques to elicit the requirements from the customer. These may include the development of scenarios (represented as user stories in agile methods), the identification of use cases, the use of workplace observation or ethnography, holding interviews, or focus groups (more aptly named in this context as requirements workshops, or requirements review sessions) and creating requirements lists. Prototyping may be used to develop an example system that can be demonstrated to stakeholders. Where necessary, the analyst will employ a combination of these methods to establish the exact requirements of the stakeholders, so that a system that meets the business needs is produced. Requirements quality can be improved through these and other methods

- Visualization. Using tools that promote better understanding of the desired end-product such as visualization and simulation.

- Consistent use of templates. Producing a consistent set of models and templates to document the requirements.

- Documenting dependencies. Documenting dependencies and interrelationships among requirements, as well as any assumptions and congregations.

Requirements analysis topics

Stakeholder identification

See Stakeholder analysis for a discussion of people or organizations (legal entities such as companies, standards bodies) that have a valid interest in the system. They may be affected by it either directly or indirectly. A major new emphasis in the 1990s was a focus on the identification of stakeholders. It is increasingly recognized that stakeholders are not limited to the organization employing the analyst. Other stakeholders will include:

- anyone who operates the system (normal and maintenance operators)

- anyone who benefits from the system (functional, political, financial and social beneficiaries)

- anyone involved in purchasing or procuring the system. In a mass-market product organization, product management, marketing and sometimes sales act as surrogate consumers (mass-market customers) to guide development of the product.

- organizations which regulate aspects of the system (financial, safety, and other regulators)

- people or organizations opposed to the system (negative stakeholders; see also Misuse case)

- organizations responsible for systems which interface with the system under design.

- those organizations who integrate horizontally with the organization for whom the analyst is designing the system.

Joint Requirements Development (JRD) Sessions

Requirements often have cross-functional implications that are unknown to individual stakeholders and often missed or incompletely defined during stakeholder interviews. These cross-functional implications can be elicited by conducting JRD sessions in a controlled environment, facilitated by a trained facilitator (Business Analyst), wherein stakeholders participate in discussions to elicit requirements, analyze their details and uncover cross-functional implications. A dedicated scribe should be present to document the discussion, freeing up the Business Analyst to lead the discussion in a direction that generates appropriate requirements which meet the session objective.

JRD Sessions are analogous to Joint Application Design Sessions. In the former, the sessions elicit requirements that guide design, whereas the latter elicit the specific design features to be implemented in satisfaction of elicited requirements.

Contract-style requirement lists

One traditional way of documenting requirements has been contract style requirement lists. In a complex system such requirements lists can run to hundreds of pages long.

An appropriate metaphor would be an extremely long shopping list. Such lists are very much out of favour in modern analysis; as they have proved spectacularly unsuccessful at achieving their aims; but they are still seen to this day.

Strengths

- Provides a checklist of requirements.

- Provide a contract between the project sponsor(s) and developers.

- For a large system can provide a high level description from which lower-level requirements can be derived.

Weaknesses

- Such lists can run to hundreds of pages. They are not intended to serve as a reader-friendly description of the desired application.

- Such requirements lists abstract all the requirements and so there is little context. The Business Analyst may include context for requirements in accompanying design documentation.

- This abstraction is not intended to describe how the requirements fit or work together.

- The list may not reflect relationships and dependencies between requirements. While a list does make it easy to prioritize each individual item, removing one item out of context can render an entire use case or business requirement useless.

- The list does not supplant the need to review requirements carefully with stakeholders in order to gain a better shared understanding of the implications for the design of the desired system / application.

- Simply creating a list does not guarantee its completeness. The Business Analyst must make a good faith effort to discover and collect a substantially comprehensive list, and rely on stakeholders to point out missing requirements.

- These lists can create a false sense of mutual understanding between the stakeholders and developers; Business Analysts are critical to the translation process.

- It is almost impossible to uncover all the functional requirements before the process of development and testing begins. If these lists are treated as an immutable contract, then requirements that emerge in the Development process may generate a controversial change request.

Alternative to requirement lists

As an alternative to requirement lists, Agile Software Development uses User stories to suggest requirements in everyday language.

Measurable goals

Best practices take the composed list of requirements merely as clues and repeatedly ask "why?" until the actual business purposes are discovered. Stakeholders and developers can then devise tests to measure what level of each goal has been achieved thus far. Such goals change more slowly than the long list of specific but unmeasured requirements. Once a small set of critical, measured goals has been established, rapid prototyping and short iterative development phases may proceed to deliver actual stakeholder value long before the project is half over.

Prototypes

A prototype is a computer program that exhibits a part of the properties of another computer program, allowing users to visualize an application that has not yet been constructed. A popular form of prototype is a mockup, which helps future users and other stakeholders to get an idea of what the system will look like. Prototypes make it easier to make design decisions, because aspects of the application can be seen and shared before the application is built. Major improvements in communication between users and developers were often seen with the introduction of prototypes. Early views of applications led to fewer changes later and hence reduced overall costs considerably.

Prototypes can be flat diagrams (often referred to as wireframes) or working applications using synthesized functionality. Wireframes are made in a variety of graphic design documents, and often remove all color from the design (i.e. use a greyscale color palette) in instances where the final software is expected to have graphic design applied to it. This helps to prevent confusion as to whether the prototype represents the final visual look and feel of the application.

Use cases

A use case is a structure for documenting the functional requirements for a system, usually involving software, whether that is new or being changed. Each use case provides a set of scenarios that convey how the system should interact with a human user or another system, to achieve a specific business goal. Use cases typically avoid technical jargon, preferring instead the language of the end-user or domain expert. Use cases are often co-authored by requirements engineers and stakeholders.

Use cases are deceptively simple tools for describing the behavior of software or systems. A use case contains a textual description of the ways in which users are intended to work with the software or system. Use cases should not describe internal workings of the system, nor should they explain how that system will be implemented. Instead, they show the steps needed to perform a task without sequential assumptions.

Requirements specification

Requirements specification is the synthesis of discovery findings regarding current state business needs and the assessment of these needs to determine, and specify, what is required to meet the needs within the solution scope in focus. Discovery, analysis and specification move the understanding from a current as-is state to a future to-be state. Requirements specification can cover the full breadth and depth of the future state to be realized, or it could target specific gaps to fill, such as priority software system bugs to fix and enhancements to make. Given that any large business process almost always employs software and data systems and technology, requirements specification is often associated with software system builds, purchases, cloud computing strategies, embedded software in products or devices, or other technologies. The broader definition of requirements specification includes or focuses on any solution strategy or component, such as training, documentation guides, personnel, marketing strategies, equipment, supplies, etc.

Types of requirements

Requirements are categorized in several ways. The following are common categorizations of requirements that relate to technical management:[1]

Business requirements

Statements of business level goals, without reference to detailed functionality. These are usually high-level (software and/or hardware) capabilities that are needed to achieve a business outcome.

Customer requirements

Statements of fact and assumptions that define the expectations of the system in terms of mission objectives, environment, constraints, and measures of effectiveness and suitability (MOE/MOS). The customers are those that perform the eight primary functions of systems engineering, with special emphasis on the operator as the key customer. Operational requirements will define the basic need and, at a minimum, answer the questions posed in the following listing:[1]

- Operational distribution or deployment: Where will the system be used?

- Mission profile or scenario: How will the system accomplish its mission objective?

- Performance and related parameters: What are the critical system parameters to accomplish the mission?

- Utilization environments: How are the various system components to be used?

- Effectiveness requirements: How effective or efficient must the system be in performing its mission?

- Operational life cycle: How long will the system be in use by the user?

- Environment: What environments will the system be expected to operate in an effective manner?

Architectural requirements

Architectural requirements explain what has to be done by identifying the necessary systems architecture of a system.

Structural requirements

Structural requirements explain what has to be done by identifying the necessary structure of a system.

Behavioral requirements

Behavioral requirements explain what has to be done by identifying the necessary behavior of a system.

Functional requirements

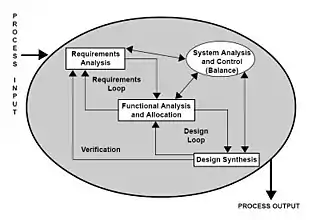

Functional requirements explain what has to be done by identifying the necessary task, action or activity that must be accomplished. Functional requirements analysis will be used as the toplevel functions for functional analysis.[1]

Non-functional requirements

Non-functional requirements are requirements that specify criteria that can be used to judge the operation of a system, rather than specific behaviors.

Performance requirements

The extent to which a mission or function must be executed; generally measured in terms of quantity, quality, coverage, timeliness or readiness. During requirements analysis, performance (how well does it have to be done) requirements will be interactively developed across all identified functions based on system life cycle factors; and characterized in terms of the degree of certainty in their estimate, the degree of criticality to system success, and their relationship to other requirements.[1]

Design requirements

The "build to", "code to", and "buy to" requirements for products and "how to execute" requirements for processes expressed in technical data packages and technical manuals.[1]

Derived requirements

Requirements that are implied or transformed from higher-level requirement. For example, a requirement for long range or high speed may result in a design requirement for low weight.[1]

Allocated requirements

A requirement that is established by dividing or otherwise allocating a high-level requirement into multiple lower-level requirements. Example: A 100-pound item that consists of two subsystems might result in weight requirements of 70 pounds and 30 pounds for the two lower-level items.[1]

Well-known requirements categorization models include FURPS and FURPS+, developed at Hewlett-Packard.

Requirements analysis issues

Stakeholder issues

Steve McConnell, in his book Rapid Development, details a number of ways users can inhibit requirements gathering:

- Users do not understand what they want or users do not have a clear idea of their requirements

- Users will not commit to a set of written requirements

- Users insist on new requirements after the cost and schedule have been fixed

- Communication with users is slow

- Users often do not participate in reviews or are incapable of doing so

- Users are technically unsophisticated

- Users do not understand the development process

- Users do not know about present technology

This may lead to the situation where user requirements keep changing even when system or product development has been started.

Engineer/developer issues

Possible problems caused by engineers and developers during requirements analysis are:

- A natural inclination towards writing code can lead to implementation beginning before the requirements analysis is complete, potentially resulting in code changes to meet actual requirements once they are known.

- Technical personnel and end-users may have different vocabularies. Consequently, they may wrongly believe they are in perfect agreement until the finished product is supplied.

- Engineers and developers may try to make the requirements fit an existing system or model, rather than develop a system specific to the needs of the client.

Attempted solutions

One attempted solution to communications problems has been to employ specialists in business or system analysis.

Techniques introduced in the 1990s like prototyping, Unified Modeling Language (UML), use cases, and agile software development are also intended as solutions to problems encountered with previous methods.

Also, a new class of application simulation or application definition tools have entered the market. These tools are designed to bridge the communication gap between business users and the IT organization — and also to allow applications to be 'test marketed' before any code is produced. The best of these tools offer:

- electronic whiteboards to sketch application flows and test alternatives

- ability to capture business logic and data needs

- ability to generate high fidelity prototypes that closely imitate the final application

- interactivity

- capability to add contextual requirements and other comments

- ability for remote and distributed users to run and interact with the simulation

See also

- Business analysis

- Business process reengineering

- Creative brief

- Data modeling

- Design brief

- Functional requirements

- Information technology

- Model-driven engineering

- Model Transformation Language

- Needs assessment

- Non-functional requirements

- Process architecture

- Process modeling

- Product fit analysis

- Requirements elicitation

- Requirements Engineering Specialist Group

- Requirements management

- Requirements Traceability

- Search Based Software Engineering

- Software prototyping

- Software requirements

- Software Requirements Specification

- Systems analysis

- System requirements

- System requirements specification

- User-centered design

References

- Systems Engineering Fundamentals Archived 2011-07-22 at the Wayback Machine Defense Acquisition University Press, 2001

- Kotonya, Gerald; Sommerville, Ian (1998). Requirements Engineering: Processes and Techniques. Chichester, UK: John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 9780471972082.

- Alain Abran; James W. Moore; Pierre Bourque; Robert Dupuis, eds. (March 2005). "Chapter 2: Software Requirements". Guide to the software engineering body of knowledge (2004 ed.). Los Alamitos, CA: IEEE Computer Society Press. ISBN 0-7695-2330-7. Retrieved 2007-02-08.

It is widely acknowledged within the software industry that software engineering projects are critically vulnerable when these activities are performed poorly.

- Project Management Institute 2015, p. 158, §6.3.2.

Bibliography

- Brian Berenbach; Daniel Paulish; Juergen Katzmeier; Arnold Rudorfer (2009). Software & Systems Requirements Engineering: In Practice. New York: McGraw-Hill Professional. ISBN 978-0-07-160547-2.

- Hay, David C. (2003). Requirements Analysis: From Business Views to Architecture (1st ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-028228-6.

- Laplante, Phil (2009). Requirements Engineering for Software and Systems (1st ed.). Redmond, WA: CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4200-6467-4.

- Project Management Institute (2015-01-01). Business Analysis for Practitioners. Project Management Inst. ISBN 978-1-62825-069-5.

- McConnell, Steve (1996). Rapid Development: Taming Wild Software Schedules (1st ed.). Redmond, WA: Microsoft Press. ISBN 1-55615-900-5.

- Nuseibeh, B.; Easterbrook, S. (2000). Requirements engineering: a roadmap (PDF). ICSE'00. Proceedings of the conference on the future of Software engineering. pp. 35–46. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.131.3116. doi:10.1145/336512.336523. ISBN 1-58113-253-0.

- Andrew Stellman & Jennifer Greene (2005). Applied Software Project Management. Cambridge, MA: O'Reilly Media. ISBN 0-596-00948-8.

- Karl Wiegers & Joy Beatty (2013). Software Requirements (3rd ed.). Redmond, WA: Microsoft Press. ISBN 978-0-7356-7966-5.

External links

- Peer-reviewed Encyclopedia Entry on Requirements Engineering and Analysis

- Defense Acquisition University Stakeholder Requirements Definition Process---Stakeholder Requirements Definition Process at the Wayback Machine (archived December 23, 2015)

- MIL-HDBK 520 Systems Requirements Document Guidance