Battle of Fort Oswego (1814)

The Battle of Fort Ontario was a partially successful British raid on Fort Ontario and the village of Oswego, New York on May 6, 1814 during the War of 1812.

| Battle of Fort Ontario | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the War of 1812 | |||||||

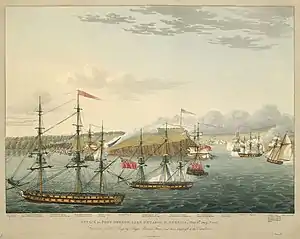

The attack on Fort Ontario, 1814. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

James Lucas Yeo Karl Viktor Fischer William Mulcaster | George Mitchell | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

550 soldiers 400 marines[1] 200 sailors 8 warships |

242 regulars 25 U.S. Navy 200 militia[2] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

17-18 killed 63-69 wounded Total: 80-87[3][4] |

6-21 killed 38 wounded 25-60 captured Total: 69-119[5][6][7] | ||||||

Background

During the early months of 1814, while Lake Ontario was frozen, the British and American naval squadrons had been building two frigates each, with which to contest command of the lake during the coming campaigning season. The British under Commodore Sir James Lucas Yeo were first to complete their frigates on 14 April, but when the Americans under Commodore Isaac Chauncey had completed their own, more powerful, frigates, Yeo's squadron would be outclassed.

Lieutenant General Sir Gordon Drummond, the Lieutenant Governor of Upper Canada, suggested using the interval during which Yeo's squadron was stronger than Chauncey's to attack the main American harbour and base at Sackett's Harbor, New York. Most of its garrison had marched off to the Niagara River, leaving only 1,000 regular troops as its garrison. Nevertheless, Drummond would require reinforcements to mount a successful attack on the strongly fortified town, and the Governor General of Canada, Lieutenant General Sir George Prevost, refused to provide these.[8]

Instead, Drummond and Yeo decided to attack the smaller post at Fort Ontario. This fort, with the nearby village of Oswego, New York, was a vital staging point on the American supply route from New York. Ordnance, food and other supplies were carried up the Mohawk River and across Lake Oneida, to Oswego, before making the final leg of the journey across the southeast corner of Lake Ontario to Sackett's Harbor.

Drummond and Yeo had reliable information that the garrison of the fort numbered only 290 regulars, and believed that thirty or more heavy guns intended for Chauncey's ships under construction at Sackett's Harbor were waiting there. They planned, by capturing Oswego, to capture these guns and thereby retain Yeo's advantage over Chauncey.[9]

Attack

Yeo's squadron embarked the landing force and set out from Kingston late on 3 May. They arrived off Oswego early in the morning, on 5 May. The troops prepared to land shortly after midday, but a southerly breeze sprang up, which made it impossible for Yeo's ships to get close enough to the shore to provide support from their guns.[10] That evening, a storm blew up, forcing the British squadron to withdraw for the night.

The British squadron returned to Oswego at eleven o'clock the next morning, and the landing proceeded. The landing force consisted of the 2nd Battalion, Royal Marines under Lieutenant Colonel James Malcolm, a company of the Glengarry Light Infantry under Captain Alexander MacMillan, a company of the Regiment de Watteville and a detachment of 200 sailors armed with boarding pikes under Captain William Mulcaster.[12] Four more companies of the Regiment de Watteville were in reserve. Lieutenant Colonel Victor Fischer, the commanding officer of the Regiment de Watteville, was in charge of the landing.[12]

Opposed to them was an American force of 242 officers and enlisted men of the 3rd U.S. Regiment of Artillery, 25 sailors of the U.S. Navy, and about 200 of the New York Militia,[2] under the command of Major George Mitchell of the 3rd Artillery. Mitchell attempted a ruse by pitching large numbers of tents near the village to exaggerate his numbers.[13][14][15] The fort was in a state of disrepair, but the delay imposed on the landing had allowed the defenders to shift extra guns to face the lake,[10] with a total of five guns in a battery in the fort: one 9-pounder and four 4 or 6-pounders.[2]

While the two British frigates (HMS Prince Regent and Princess Charlotte) engaged the fort, the guns of six sloops and brigs swept the woods and landing beaches.[16] The British landed at about two o'clock. Almost all the troops landed in deep water and their ammunition was soaked and made useless. Nevertheless, they fixed their bayonets and advanced under heavy fire. While the company of the Glengarry Light Infantry cleared woods to the left of the main attack and the sailors advanced on the village, the main body of the troops made a frontal attack against the fort. American foot soldiers drawn up on the glacis fell back into the fort.[10] As the attackers reached the top of the glacis, the defenders abandoned the fort and fled.

Casualties

The official British Army casualty return, signed by Lieutenant Colonel John Harvey, the Deputy Adjutant-General, gave 7 killed and 33 wounded for the 2nd Battalion, Royal Marines, 8 killed and 17 wounded for the Regiment de Watteville and 9 wounded for the Glengarry Light Infantry.[3] The separate Royal Navy casualty return for the engagement, signed by Yeo, gave 3 killed and 10 wounded for the Navy and 6 killed and 27 wounded for the Royal Marines.[4] This would give a grand total of either 18 killed and 69 wounded or 17 killed and 63 wounded, depending upon whether the Army or Navy casualty list is correct for the Royal Marines' losses. Captain Mulcaster was seriously wounded by grapeshot, losing a leg.[17]

The American losses are hard to determine. Mitchell's casualty return, which apparently included the U.S. regular troops only, stated the loss as 6 killed, 38 wounded and 25 missing.[5] Captain Rufus McIntire of the 3rd U.S. Artillery reported to an associate, "Our loss is five killed, 28 wounded, 3 since dead, about 24 prisoners and 11 missing. Lt. [Daniel] Blaney killed and only one other officer slightly wounded."[18] General Drummond's report of the engagement to Sir George Prevost stated that the British captured "about 60 men, half of them severely wounded".[6] Another British report, however, said that only 25 American soldiers and 1 "civilian" (possibly a militiaman) were captured.[7] Still another British account said that 1 officer and 20 enlisted men of the Americans were found dead on the battlefield.[7]

Result

The British gathered 2,400 barrels of useful supplies of all description; flour, pork, salt, bread and ordnance stores. They also captured a few small schooners, including USS Growler, which had previously been captured by the British the year before but then recaptured by the Americans. Growler contained seven of the invaluable cannon destined for Chauncey. Although the Americans had hastily scuttled the schooner to prevent it being captured, the British were able to raise it.[19] Lieutenant Phillpotts of the Corps of Royal Engineers set fire to and destroyed the fort, barracks and stores which could not be moved.[20] The British withdrew at about four o'clock in the morning on 7 May.

The British had missed twenty-one more guns which had still been en route to Oswego, and were 12 miles (19 km) away at Oswego Falls. Rather than launch an expedition up the Oswego River, Yeo mounted a blockade of Sackett's Harbor to prevent them reaching Chauncey. The Americans tried to move them to Sackett's Harbor in launches and small boats but were intercepted. British marines and sailors then mounted a "cutting-out" attack against them but failed, with 200 marines and sailors ambushed and captured at the Battle of Big Sandy Creek.

Once Chauncey had received the guns and fitted out his squadron, he commanded the lake from the end of July 1814 until late in the year.

See also

Notes

- Letter from General Drummond to Sir George Prevost dated 3 May 1814, citing a land forces strength of 24 Artillerymen, 20 Sappers, 450 De Wattevilles, 50 Glengarry Light Infantry, along with 9 Marine rocketeers and 350 men of the 2nd (Royal Marines) Battalion, in addition to the Sailors and Marines of the Lake Ontario squadron

- Johnston, p.139

- Wood, p.59

- Wood, pp.64-65

- Quimby, p.509

- Cruikshank, p.336

- Johnston, p.142

- Hitsman, p.208

- Hitsman, p.209

- "Contemporary British account of the battle". napoleonic-series.org. Retrieved 8 October 2022.

- Lossing, Benson (1868). The Pictorial Field-Book of the War of 1812. Harper & Brothers, Publishers. p. 796.

- "THE WAR OF 1812: European Traces in a British-American Conflict" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 December 2021.

- Crawford, pp.474-476

- Hannings, pp. 212-211

- Lossing, pp.704-798

- Roosevelt, p.198

- Hitsman, p.210

- McIntire, p. 314.

- Roosevelt, p.199

- Porter, Maj Gen Whitworth (1889). History of the Corps of Royal Engineers Vol I. Chatham: The Institution of Royal Engineers. p. 258.

References

- Crawford, Michael J. (2003). The Naval War of 1812, A Documentary History, V. 3: 1814-1815, Chesapeake Bay, Northern Lakes, and Pacific Ocean. Bolton Landing, NY: Dept. of the Navy; 1st edition. ISBN 0-16-051224-7.

- Cruikshank, Ernest A. (1971) [1908]. The Documentary History of the Campaign upon the Niagara Frontier in 1812-14. Volume IX: December, 1813 to May, 1814 (Reprint ed.). by Arno Press. ISBN 0-405-02838-5.

- Chester, Gregory Battle of Big Sandy: War Of 1812 Publisher: George "Greg" Gregory Chester, 2007 http://hasjny.tripod.com/id11.html ISBN 978-0-9791135-0-5 contains the names of the casualties at Oswego

- Hannings, Bud (2012). The War of 1812: A Complete Chronology with Biographies of 63 General Officers. Jefferson, NC: McFarland; 1st edition. ASIN B00BP5MZZC – via Google Books.

- Hitsman, J. Mackay, The incredible War of 1812, Robin Brass Studio, Toronto, ISBN 1-896941-13-3

- James, William (1818). A Full and Correct Account of the Military Occurrences of the Late War Between Great Britain and the United States of America, Volume II. London: Published for the Author. ISBN 0-665-35743-5.

- Johnson, Crisfield. ... History of Oswego County, New York. Philadelphia: L.H. Everts &, 1877.

- Johnston, Winston (1998). The Glengarry Light Infantry, 1812-1816. Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island: Benson Publishing. ISBN 0-9730501-0-1.

- K. G. S. "The Raid on Oswego in 1814: A Documentary History" (self-published), 2020.

- Lossing, Benson J. (2014). The pictorial field-book of the war of 1812; or, Illustrations, by pen and pencil, of the history, biography, scenery, relics, and traditions of the last war for American independence. Pearl Street, NY: Harper & brothers. ASIN B00IQ84RM0 – via Google Books.

- McIntire, Rufus, correspondence, New York State Library, Manuscripts & Special Collections, SC4150, transcribed in Fredriksen, John C., ed., “The War of 1812 in Northern New York: The Observations of Captain Rufus McIntire,” New York History, Vol. 68 (July, 1987), 297-324.

- NICOLAS, Paul Harris (1845) [2010]. Historical Record of the Royal Marine Forces, Volume 2, 1805-1842. BiblioBazaar, LLC. pp. 257–259. ISBN 1-142-42683-1.

- Quimby, Robert S. (1997). The U.S. Army in the War of 1812: An Operational and Command Study. East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University Press. ISBN 0-87013-441-8.

- Roosevelt, Theodore, The Naval War of 1812, Modern Library, New York, ISBN 0-375-75419-9

- Wood, William (1968). Select British Documents of the Canadian War of 1812. Volume III, Part 1. New York: Greenwood Press.

External links

Media related to Battle of Fort Oswego (1814) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Battle of Fort Oswego (1814) at Wikimedia Commons- "Contemporary British account of the battle". napoleon-series.org. Retrieved 8 October 2022.