Battle of St. Michaels

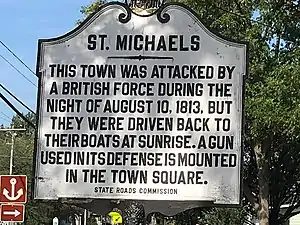

The Battle of St. Michaels was an engagement contested on August 10, 1813, during the War of 1812. British soldiers attacked the American militia at St. Michaels, Maryland, which is located on Maryland's Eastern Shore with access to Chesapeake Bay. At the time, this small town was on the main shipping route to important cities such as Baltimore and Washington, D.C.

| Battle of St. Michaels | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the War of 1812 | |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| George Cockburn | Perry Benson | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

Royal Navy * 1st Bn Royal Marines * 2nd Bn Royal Marines British Army * 102nd Regiment of Foot |

12th Maryland Brigade * Parrott Point Gun Battery * Dawson's Wharf Battery * Easton Vol. Artillerists | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Land: 300 Sea: unknown | Land: 500 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 29 | 0 | ||||||

Although St. Michaels had little importance compared to Washington and Baltimore, it was a target for the British because of its ship building and its connection with the town of Easton, which was the largest community in the Maryland Eastern Shore region. St. Michaels is located on the St. Michaels (later named Miles) River, which could be used with smaller boats to get within three miles (4.8 km) of Easton.

St. Michaels was attacked early in the morning before sunrise, when British forces arrived on the shore near the town. They quickly disabled an artillery battery, and returned to their boats. As they maneuvered their flotilla closer to the town, two other batteries manned by local militia opened fire. A boom placed across the mouth of the town's harbor successfully prevented the British from getting closer. Although the British returned fire, they eventually retreated to their base at Maryland's Kent Island. The locals suffered no casualties, while the British had casualties and damage to at least one barge. According to local legend, the citizens of St. Michaels hung lanterns in trees to fool the British artillerists, causing them to overshoot most of the town's buildings.

Background

On June 17, 1812, the United States Senate approved a resolution passed by the United States House of Representatives that declared war against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. President James Madison signed the resolution into law on June 18.[1][2] The country was not united in its feelings toward Great Britain. Many members of the Federalist political party, a coalition of bankers and businessmen, were against the war.[3][4] Contrary to the Federalists, members of the Democratic-Republican Party, who had a numerical superiority, believed a war was justified.[5]

After the declaration of war, the British government declared the ports of the United States to be in a state of blockade.[6] They began stricter enforcement of the blockade in 1813, when ships were sent to close the port of New York and others further south, including those on the Chesapeake Bay. Early in February 1813, British ships under the command of Rear Admiral George Cockburn took possession of Hampton Roads at the mouth of Chesapeake Bay, which stopped traffic in and out of the bay. This effectively closed major ports such as Norfolk in Virginia and the Port of Baltimore in Maryland.[6]

Beginning in spring, Cockburn conducted raids on towns along the Chesapeake. The raids involved the destruction or removal of property including crops and livestock.[7] On May 3, Cockburn burned most of Havre de Grace, Maryland.[8][Note 1] Additional Maryland coastal towns, Georgetown and Fredericktown, were burned on May 6.[11] First Lady Dolley Madison called Cockburn's raids "savage", and Cockburn threatened to capture and parade her through London.[7] Cockburn established a policy that if a town kept no guns or militia, he would leave them unharmed.[12][Note 2]

Vice Admiral Sir John Borlase Warren was Cockburn's immediate superior, and he was headquartered in Bermuda.[13] Warren believed he did not have enough ships to blockade the American coast. During May, he received two battalions of marines and additional ships. He issued a May 26 proclamation that New York and the Mississippi River were in a state of formal blockade. The same proclamation also listed as blockaded the South Carolina ports at Charleston, Port Royal, and Savannah.[12] Royal Marines were sent to the Chesapeake Bay because of its naval stores, ships, dockyards, and foundries. Norfolk, Baltimore, and Washington, D.C. were among the immediate targets.[12]

Opposing forces

United Kingdom

Admiral Sir John Borlase Warren was the commander of North America and the West Indies during the summer of 1812, and in January 1813 Rear Admiral George Cockburn reported to Warren in HMS Marlborough.[13] For the raid on St. Michaels, Cockburn had eight ships and 45 barges, including two battalions of Royal Marines and an army regiment.[14] The forces that came ashore were under the command of Lieutenant James Polkinghorne of the Royal Navy. After the battle, he filed a report with Commander Henry Loraine Baker of the Royal Navy.[15] Baker commanded HMS Conflict, a sloop with 10 to 12 guns (a.k.a. cannons or artillery pieces).[14] The men used barges, which were propelled by oars and small sails, to reach the shore.[16] The barges had a small gun, or "carronade".[15]

United States

The United States had few federal troops near St. Michaels in 1813. Fighting was usually conducted by the state militia. Maryland's militia was organized into three divisions with a total of 12 brigades and 11 cavalry districts.[17] Much of the Talbot County militia was formed in 1807 after the attack on the American USS Chesapeake by the British HMS Leopard.[18] Brigadier General Perry Benson, who was a veteran of the American Revolutionary War, commanded the militia of Talbot, Caroline, and Dorchester counties. His force at the battle consisted of two regiments, several companies of cavalry, and three artillery batteries.[19]

- 12th Maryland Brigade was commanded by Brigadier General Benson.[20]

- 4th Maryland Regiment was commanded by Lieutenant Colonel William B. Smyth. It consisted of men mostly from Easton, and had an artillery company.[20]

- 26th Maryland Regiment was commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Hugh Auld, and had companies from the St. Michaels area.[21]

- 9th Cavalry District was commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Edward Lloyd, and included companies from Easton, St. Michaels, and Trappe.[21]

- two batteries (a third battery was the company that was part of the 4th Maryland Regiment)[21]

Benson's brigade was large, but its training was inadequate. It also had a shortage of weaponry. Muskets were used by companies near threatened positions, and then transferred to the next threat when the original threat passed.[18] Although Benson had a large force at St. Michaels, the fighting was conducted by the artillerists.[22]

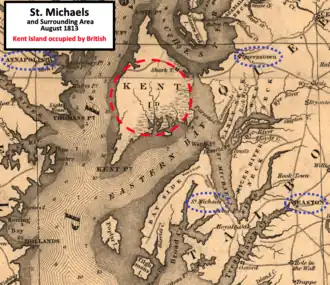

Prelude

The British captured Maryland's Kent Island during early August 1813. The island is located north of St. Michaels and across the bay from the Maryland state capital Annapolis. The British landed about 3,000 men on the island, but faced no resistance because most of the inhabitants fled when they learned of the invasion.[23][Note 3] The island had food and fresh water, and would provide a base for operations against Maryland's Eastern Shore, Annapolis, Baltimore, and Washington.[25]

During this time, the British had ships in Eastern Bay between Kent Island and St. Michaels, causing alarm throughout Talbot County.[26] St. Michaels was a target because of its shipbuilding, and it had at least six vessels in the process of being built.[Note 4] It was also an outport for the town of Easton, which was largest town on Maryland's Eastern Shore.[26] Easton had the only armory on Maryland's Eastern Shore, a bank, and plenty of goods for the British to plunder.[Note 5] Boats and small vessels could be used on the St. Michaels River to get within three miles (4.8 km) of Easton.[24][Note 6] A second water route to Easton, Tredhaven Creek, was protected by a six-gun battery called Fort Stokes.[19][Note 7]

Preparing for the British

"Americans had acquired new allies while the British were upon Kent Island...mosquitos, whose bloodthirsty numbers it was thought would soon drive the enemy to take refuge on board his ships."

Washington National Intelligencer[24]

Militia from throughout Talbot County were sent to St. Michaels to stand with the local infantry company, Saint Michaels Patriotic Blues, commanded by Captain Joseph Kemp with the artillery men commanded by Lieutenant William Dodson.[26][Note 8] Kemp's company and at least three of the Easton companies wore uniforms.[32] The militia troops totaled to about 500 men, and they were led by Brigadier General Benson, Colonel Auld, and Colonel Thomas Jones.[Note 9] The men were quartered in the town's two churches.[34]

Benson placed three artillery batteries around the town. East of town, Dodson commanded a group of 30 men with a battery of four guns behind a small fortification. The location was Parrott's Point (also known as Parrott Point), and it was at the mouth of the town's harbor on the south side.[35] A boom was placed across the mouth of the harbor to prevent vessels from entering. Within the town at Dawson's wharf (at the end of Mulberry Street), a two-gun battery on wheels was commanded by John Graham with John Thompson and Wrightson Jones manning the 6-pounder guns.[36] Two more guns were placed outside of town in case the British landed behind the town and marched toward it. This battery of two guns was commanded by Lieutenant Clement Vickers and manned by men from Easton in the company Talbot Volunteer Artillerists.[35]

Videttes were stationed at various points to watch the British at Kent Island, and they reported to either Colonel Auld in St. Michaels or Brigadier General Benson in Easton.[26] A British brig was seen making reconnaissance north of the town near Deep Water Point on the St. Michaels River. A deserter crossed the Eastern Bay and landed at Bayside. He said the British planned to attack St. Michaels within the week, but were worried about what they thought was a 10-gun battery.[37]

Battle

Early in the morning on August 10, a total of 300 British soldiers and marines in nine to eighteen barges moved up the St. Michaels River.[37][Note 10] The river was over one mile (1.6 km) wide, and they traveled in fog and darkness along the shore opposite St. Michaels. Videttes on the St. Michaels side of the river did not observe the British force as it moved up the river and passed the harbor.[37] The force crossed the river and arrived at about 4:00 am near Parrott's Point in foggy darkness. They disembarked in water near the flank of the Dodson's guns and breastworks, and were discovered by African American John Stevens.[38]

Dodson's surprised men panicked, and most of them dropped their weapons and fled through a cornfield back to town. The British fired a volley from their muskets at the fleeing men, but damaged only the corn.[39] The only men that remained with the guns were Dodson, Stevens, and a third man. The three men were able to re-position one gun, loaded with ball and canister, where it could fire effectively on the British. Having seen Dodson's men run, the British expected to capture the battery without resistance, but instead received the contents of a nine-pounder cannon. Despite their casualties, they continued to the guns while Dodson and his two men fled. The guns were captured and disabled.[40]

Concluding an important part of their mission, the British returned to the barges with their dead and wounded. The barges moved to less than half a mile (0.8 km) from town, but were unable to cross the boom that had been placed earlier. They fired at the town from two guns, then assumed a position further out in the river, where they continued firing "with much vigor".[41] A St. Michaels legend is that the town hung lamps in trees away from the houses, confusing the British and causing them to overshoot their targets.[42] Graham's battery at Dawson's wharf returned fire, and eventually fired a total of 10 shots.[43] Hearing the cannon fire, the Easton artillerists moved their battery from the Bayside road to Mill Point in town, and fired a total of five shots as the British began to retreat.[41][43][Note 11]

By 9:00 am the artillery duel was over, and the British returned to their base.[45] Benson, his infantry, and his cavalry were waiting at the town square. They outnumbered the British force, but did not need to engage.[46] The town had been successfully defended, and did not suffer the same fate as Havre de Grace.[47]

Casualties

Lieutenant Polkinghorne's report said his British ground force had losses of "only two wounded".[15] Discussing American casualties, Benson's report mentioned that "some of the houses were perforated", but no "injury to any human being".[43] He also implied that the British had casualties, mentioning "much blood on the grass at the water" where the British barges were located.[43] A deserter from the Royal Navy claimed their casualties were one captain, one lieutenant of the marines, and twenty-seven privates.[48] He also thought one of the barges had significant damage. A second deserter believed that one of the British dead was an officer.[48][Note 12]

Aftermath

The British threatened St. Michaels again on August 26.[42] This time, they sent 2,100 men in 60 barges. They landed about six miles (9.7 km) north of town, and 1,800 men met 500 Talbot County militia that included infantry, cavalry, and artillery. The largest Maryland Eastern Shore battle of the war lasted only a few volleys because the British withdrew.[42]

Warren reported that he had problems with desertions in the army and poor discipline in the marines.[49] His men began preparing to sail away from Kent Island on August 22 after determining that attacks on Annapolis and Baltimore would be ill-advised because those American cities had received substantial reinforcements.[25] He also wished to sail to Halifax, Canada, before the start of hurricane season.[49] By September, Warren departed to Halifax, and Cockburn had departed for Bermuda. A small "skeleton force" was stationed at the Virginia Capes for blockade purposes.[50]

Performance and legend

Lieutenant Polkinghorne of the British Royal Navy reported that he "deemed the object of the enterprize fulfilled".[15] He did not see any vessels, and one of the reasons the British attacked St. Michaels was to destroy ships being built there. He captured a battery, split the carriages, and destroyed all ammunition.[15] Contrary to Polkinghorne's report, a deserter claimed the expedition was considered a failure, with the reason given was that the expedition leader expected to meet unreliable militia, but instead had too small of a force to cope with regulars.[51] Shots from the British six-pounder guns were generally high, and hit the roofs or higher bables of some houses.[46] Warren's August 23 report to First Secretary of the Admiralty John W. Croker mentioned an attack upon Queenstown, but did not mention St. Michaels.[25]

The American artillerists were said to be more effective than their British counterparts.[46] In addition to the blood found at the site where the British landed their barges, one newspaper reported that three barges were struck by shots fired by the town's artillery.[52] Benson's report said the "militia generally behaved well", and did not mention that some fled without firing a shot.[53] For years afterward, two of the Easton companies feuded with each other over their performance at the battle.[52]

The local story about the August 10 battle is that the town's citizens hung lanterns high in trees, fooling the British into firing over the town.[42] Some even say that the only house hit by the British was the house of shipbuilder William Merchant.[54][Note 13] However, Benson's report said "Some of the houses were perforated....", and did not mention any deception.[22] More doubt can be placed on the legend since it was probably already daylight by the time the British fired at the town.[42]

Preservation

The St. Michaels Historic District has over 300 structures.[56] William Merchant's home, now known as the Cannonball House, in addition to being part of the historic district, has been part of the National Register of Historic Places since 1983.[56][55] The battle, also commemorated by the Star-Spangled Banner National Historic Trail, is discussed by two local museums: the St. Michaels Museum at St. Mary's Square, and the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum.[57][58][59]

Notes

Footnotes

- Cockburn said his original intention at Havre de Grace was to destroy the iron works, but he burned the town because four men were killed and one wounded when he landed with a flag of truce.[9] Another source says that from Cockburn's point of view, the burning of Havre de Grace was justified because the town had an artillery battery and because the town practiced dishonorable warfare by shooting from behind trees and houses.[10]

- In mid-August 1814, Cockburn was involved in the Burning of Washington—a highlight of his career.[7]

- Another source says the British occupying force on Kent Island consisted of 2,000 troops and 25 to 30 ships.[24]

- Vessels were either being repaired or built at the shipyards of Thomas L. Haddaway, Impey Dawson, Joseph Kemp, John Wrightson and John Davis. Outside of town, the yards of Colonel Perry Spencer and Richard Spencer were also building vessels.[26]

- As a precaution, Easton's bank sent its specie to Lancaster, Pennsylvania.[27]

- The St. Michaels River, also called Michaels River, is now called Miles River.[28] It is believed that the name change came from the local Quakers refusing to use the term "Saint", and therefore calling the river the "Michaels River". Over time, "Michaels" became "Miles".[29]

- Tredhaven Creek, also known as Third Haven Creek, is now called Tred Avon River.[30]

- Dodson is often called "Captain Dodson" because he was a packet boat captain.[31]

- Marine describes Benson's force as "about five hundred volunteers".[33] Another source says "reports vary in their estimates from three hundred to six hundred."[26]

- Although Benson's report said the British were in eleven barges, other sources have said from nine to eighteen.[22]

- The Easton artillery was moved to the harbor at Mill Point, where Green Street ends near Church cove.[44]

- Additional sources tend to agree with the higher count for British casualties. Marine lists the British casualties as two officers and twenty-seven men killed and wounded, with several barges destroyed.[43] Sheads says two officers and twenty-six marines killed or wounded.[45]

- A cannonball was said to have grazed the chimney of the William Merchant (now "Cannonball House") house, ricocheted, and flew through a southwest dormer window. This left burn marks on the stairway.[55] Merchant's wife and daughter were in the house but not injured.[54]

Citations

- "Declaration of War with Great Britain, 1812". United States Senate. Archived from the original on 2021-11-09. Retrieved 2021-11-09.

- Tilghman & Harrison 1915, pp. 143–144

- "Ohio History Central - Federalist Party". Ohio History Connection. Retrieved 2022-02-23.

- "Federalists oppose Madison's War". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved 2022-02-23.

- Tilghman & Harrison 1915, p. 144

- Tilghman & Harrison 1915, p. 148

- "The first step was plunder without distinction". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Archived from the original on 2021-10-20. Retrieved 2021-10-20.

- "War of 1812 Timeline". American Battlefield Trust. Archived from the original on 2021-10-20. Retrieved 2021-10-20.

- Marine 1913, p. 54

- Morriss 1997, p. 92

- "Kitty Knight". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Archived from the original on 2021-10-20. Retrieved 2021-10-20.

- Morriss 1997, p. 93

- Morriss 1997, p. 87

- Sheads & Turner 2014, p. 25

- Dudley 1992, p. 381

- Dudley 1992, pp. 374–375

- Sheads & Turner 2014, p. 17

- Tilghman & Harrison 1915, p. 146

- Sheads & Turner 2014, p. 44

- Sheads & Turner 2014, p. 21

- Sheads & Turner 2014, p. 22

- Tilghman & Harrison 1915, p. 169

- Marine 1913, p. 53

- Tilghman & Harrison 1915, p. 161

- Dudley 1992, p. 382

- Tilghman & Harrison 1915, p. 162

- Tilghman & Harrison 1915, p. 150

- "Miles River". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved December 20, 2021.

- Tilghman & Harrison 1915, p. 316

- "Tred Avon River". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved November 15, 2021.

- Hall 1912, p. 660

- Tilghman & Harrison 1915, p. 158

- Marine 1913, p. 55

- Tilghman & Harrison 1915, pp. 162–163

- Tilghman & Harrison 1915, p. 163

- Tilghman & Harrison 1915, pp. 163–164

- Tilghman & Harrison 1915, p. 165

- Tilghman & Harrison 1915, pp. 165–166

- Tilghman & Harrison 1915, p. 166

- Tilghman & Harrison 1915, pp. 166–167

- Tilghman & Harrison 1915, p. 167

- "The Town that Fooled the British?". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Archived from the original on 2021-10-21. Retrieved 2021-10-21.

- Marine 1913, p. 56

- Tilghman & Harrison 1915, p. 164

- Sheads & Turner 2014, p. 45

- Tilghman & Harrison 1915, p. 168

- Tilghman & Harrison 1915, pp. 170–171

- Tilghman & Harrison 1915, p. 171

- Dudley 1992, p. 383

- Dudley 1992, p. 384

- Tilghman & Harrison 1915, p. 172

- Tilghman & Harrison 1915, p. 170

- Tilghman & Harrison 1915, pp. 168–169

- Pekow, Charles (June 25, 1993). "The Storied St. Michaels". Washington Post. Archived from the original on December 17, 2021. Retrieved November 17, 2021.

- "National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form - Cannonball House" (PDF). Maryland Historical Trust, U.S. Department of the Interior. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-10-23. Retrieved 2021-10-23.

- "National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form - St. Michaels Historic District" (PDF). Maryland Historical Trust, U.S. Department of the Interior. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-10-24. Retrieved 2021-10-24.

- "Star-Spangled Banner National Historic Trail - Interpretive Plan" (PDF). National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. p. 16. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-11-23. Retrieved 2021-11-23.

- "St. Michaels Museum at St. Mary's Square". St. Michaels Museum. Archived from the original on November 28, 2021. Retrieved November 17, 2021.

- "Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum". Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum. Archived from the original on November 17, 2021. Retrieved November 17, 2021.

References

- Dudley, William S., ed. (1992). Naval War of 1812; A Documentary History - Volume II. Washington, District of Columbia: Naval Historical Center, Department of Navy. ISBN 978-0-16002-042-1. OCLC 12834733. Archived from the original on December 17, 2021. Retrieved November 13, 2021.

- Hall, Clayton Colman, ed. (1912). Baltimore Its History and its People – Volume III—Biography. New York, New York: Lewis Historical Publishing Company. OCLC 1178422. Archived from the original on December 17, 2021. Retrieved October 26, 2021.

- Marine, William Matthew (1913). Dielman, Louis Henry (ed.). The British Invasion of Maryland, 1812-1815. Baltimore, Maryland: Society of the War of 1812 in Maryland. ISBN 978-0-80630-760-2. OCLC 3120839. Archived from the original on 2021-12-17.

- Morriss, Roger (1997). Cockburn and the British Navy in Transition: Admiral Sir George Cockburn, 1772-1853. Columbia, South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-57003-253-0. OCLC 1166924740.

- Sheads, Scott S.; Turner, Graham (2014). The Chesapeake Campaigns 1813-15: Middle Ground of the War of 1812. Oxford, Oxfordshire, England: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78096-852-0. OCLC 875624797.

- Tilghman, Oswald; Harrison, Samuel A. (1915). History of Talbot County, Maryland, 1661-1861, Volume II. Baltimore, Maryland: Williams and Wilkins Company. OCLC 1541072. Archived from the original on December 17, 2021. Retrieved October 3, 2021.

Further reading

- Neimeyer, Charles P.; Center of Military History United States Army (2014). The Chesapeake Campaign 1813-1814 (PDF). Washington, District of Columbia: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. ISBN 978-1-50564-644-3. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 13, 2021. Retrieved November 9, 2021.

External links

- The Town That Fooled the British, St Michaels MD - YouTube

- St. Michaels Harbor - YouTube (31 seconds)

- War of 1812 Chesapeake Campaign... - U.S. Army