Rafael Cancel Miranda

Rafael Cancel Miranda (July 18, 1930 – March 2, 2020) was a poet, political activist, member of the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party and an advocate of Puerto Rican independence. On March 1, 1954, Cancel Miranda and three other Nationalists (Lolita Lebrón, Andrés Figueroa Cordero, and Irvin Flores Rodríguez) attacked the House of Representatives while it was in session at the United States Capitol building, firing 30 shots and injuring five Congressmen. The four were arrested, convicted, and sentenced to long prison terms. In 1979, Cancel Miranda's sentence was commuted by United States President Jimmy Carter.[1]

Rafael Cancel Miranda | |

|---|---|

| Born | July 18, 1930 |

| Died | March 2, 2020 (aged 89) |

| Political party | Puerto Rican Nationalist Party |

| Movement | Puerto Rican Independence |

| Spouse | Carmen Jiménez Teruel |

| Notes | |

Rafael Cancel Miranda was the only Nationalist jailed in Alcatraz. | |

| Part of a series on the |

| Puerto Rican Nationalist Party |

|---|

|

Early years

Cancel Miranda was born in the town of Mayagüez, located on the western coast of Puerto Rico. His father, Rafael Cancel Rodríguez, was president of the Mayagüez chapter of the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party and his mother was a member of the Daughters of Freedom, an organization which was the women's branch of the Nationalist Party. His father, a businessman and owner of a furniture store, had been imprisoned because of his political beliefs.[2]

Ponce massacre

| External audio | |

|---|---|

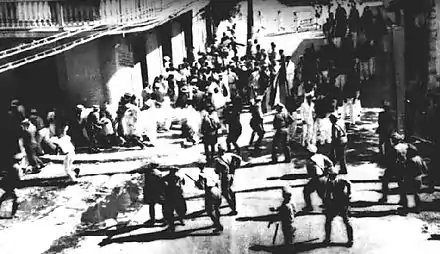

In March 1937, when Cancel Miranda was seven years old, his mother and father traveled to the city of Ponce to participate in a march organized by the Nationalist Party. He and his sisters couldn't go because they were sick with measles. The march, which was scheduled for March 30 (Palm Sunday), was organized to commemorate the ending of slavery in Puerto Rico by the governing Spanish National Assembly in 1873, and to protest the incarceration by the U.S. Government of Nationalist leader Pedro Albizu Campos on sedition charges.[3]

Upon learning of the planned protest, however, the colonial Governor of Puerto Rico at the time, General Blanton Winship, who had been appointed by US President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, demanded the immediate withdrawal of the permits. They were withdrawn a short time before the march was scheduled to begin. As "La Borinqueña", Puerto Rico's national anthem, was being played, the demonstrators began to march.[3] They were then fired upon for over 15 minutes by the police from four different positions. About 235 people were wounded and nineteen were killed.[4] Among the dead were 17 unarmed civilians and two police officers at the hands of the Insular Police.[5]

Ultimately, responsibility for the massacre fell on Governor Winship, and he is considered to have, in effect, ordered the massacre.[6] Many were chased by the police and shot or clubbed at the entrance of their houses as they tried to escape. Others were taken from their hiding places and killed. Leopold Tormes, a member of the Puerto Rico legislature, told reporters how a policeman murdered a nationalist with his bare hands. Dr. José N. Gándara, one of the physicians who assisted the wounded, testified that wounded people running away were shot, and that many were again wounded by the clubs and bare fists of the police. No arms were found in the hands of the civilians wounded, nor on the dead ones. About 150 of the demonstrators were arrested immediately afterward; they were later released on bail. The incident is known as the Ponce massacre.[7]

The white nurse's uniform of Cancel Miranda's mother was soaked with blood as she crawled over bodies in search of her husband. Miraculously, they both managed to return home unharmed. After the family returned home, Cancel Miranda committed his first political act in his first grade class in school when he refused to salute the American flag which at the time was mandatory.[2]

Political activist

Cancel Miranda joined the Cadets of the Republic (Cadetes de la República), the youth organization of the Nationalist Party, and organized nationalist youth committees in different towns. His group had a radio program and a small newspaper.[2] As a cadet, Cancel Miranda went to welcome Albizu Campos in December 1947, when the Nationalist Party leader returned from the United States after serving out a ten-year prison sentence – first in the U.S. penitentiary in Atlanta, then in New York – on charges of conspiracy to overthrow the U.S. government and "inciting rebellion" against it. Following World War II, there was widespread resistance to Washington's attempt to impose English as the main language of instruction in Puerto Rico's schools. Cancel Miranda was among those who participated in a school strike to this respect, two months before his graduation and was expelled from school. He then went to San Juan to finish high school.[2][8]

Puerto Ricans became U.S. citizens as a result of the 1917 Jones-Shafroth Act and those who were eligible, with the exception of women, were expected to serve in the military, either voluntarily or as a result of the military draft (conscription).[9] In 1948, Cancel Miranda, then eighteen and in high school, refused to be drafted into the military. One day, he was walking to school in San Juan with other students, and there was a car with four FBI agents at the corner of his house. He handed his books to the other students to take them to the place where he was living. The men arrested him and charged him with refusing the U.S. draft. The U.S. Federal Court in Puerto Rico sentenced him to two years and one day and he was sent to a prison in Tallahassee, Florida, where he remained from 1949 to 1951. During his stay in prison he confronted a prison guard because of the racist segregation inside prison walls. Under Jim Crow legislation at the time, the prison dormitories and lunch areas were segregated with areas for black prisoners and areas for white prisoners. Puerto Ricans were sent to either black or white areas, depending on their skin tone. Cancel was placed in the white area but said he "dined with the black prisoners" when he wanted to.[2][8]

Self exile in Cuba

In the 1950s, the United States entered the Korean War. Believing that he was to be drafted by the US Military and that he would once again face a prison term for refusing, Cancel Miranda followed the advice of his wife and his sister Zoraida and went into a self exile in Cuba. Cancel Miranda arrived in the city of Miranda using a different identity, Robert Rodríguez. Cuba at that time was governed by Carlos Prío Socarrás. He moved to Havana where, with the help of Albizu Campos' son, Pedro Albizu Meneses, he found a job with the Public Works Department. After a while, he went to work for the Raymond Concrete Pipe Co. which was building the Línea Street Tunnel, which connects the two banks of the Almendares River.[10]

On October 30, 1950, a Nationalist Party uprising occurred in Puerto Rico. The uprising was a call for independence against the United States Government's rule of Puerto Rico. It was also a protest against the approval of the creation of the political status the "Free Associated State of Puerto Rico" or how it is legally known, the "Commonwealth of Puerto Rico" ("Estado Libre Asociado") for Puerto Rico which was considered a colonial farce.[11] Numerous Nationalists were arrested, among them Cancel Miranda's father. In 1951, he published an article in a Havana paper to commemorate the first anniversary of that uprising. The United States embassy learned about it and demanded that the Prío Socarrás government turn him over along with another Puerto Rican, Reynaldo Trilla, but the Cuban authorities ignored them.[10]

Aracelio Azcuy, a politician of the Civil Damages Office and supporter of Prío Socarrás, used to ask Cancel Miranda to campaign for him, to write his speeches. On March 10, 1952, Fulgencio Batista led a military coup overthrowing Prío Socarrás' government. After the coup, Batista's police arrested Cancel Miranda and Trilla. They were sent to the Tiscornia prison until August 1952, when they both were expelled from Cuba.[10]

Assault on the House of Representatives

Cancel Miranda migrated to Brooklyn, New York City, where he joined his wife. He found work in a shoe factory as a press operator. In New York, he met fellow Nationalists Lolita Lebrón, a sewing machine operator, Irvin Flores Rodríguez, a furniture factory employee and Andrés Figueroa Cordero, who worked in a butcher shop.

Attack preparations

Albizu Campos had been corresponding with 34-year-old Lolita Lebrón from prison and chose a group of nationalists who included Cancel Miranda, Irvin Flores Rodríguez and Andrés Figueroa Cordero to attack locations in Washington, D.C. Upon receiving the order she communicated it to the leadership of the Nationalist party in New York and, although two members unexpectedly disagreed, the plan continued.[12] Lebrón decided to lead the group, even though Albizu Campos did not order her to directly take part in the assault.[12] She studied the plan, determining the possible weaknesses, concluding that a single attack on the House of Representatives would be more effective. The attack was planned for March 1, 1954, as the anniversary of inauguration of the Conferencia Interamericana (Interamerican Conference) in Caracas.[12] Lebrón intended to call attention to Puerto Rico's independence cause, particularly among the Latin American countries participating in the conference.

Trial and imprisonment

Cancel Miranda and his group were charged with attempted murder and other crimes. The trial began on June 4, 1954, with judge Alexander Holtzoff presiding over the case, under strict security measures. A jury composed of seven men and five women was assembled, their identities were kept secret by the media. The prosecution was led by Leo A. Rover, as part of this process 33 witnesses testified.[13] Ruth Mary Reynolds, the "American/Puerto Rican Nationalist" and the organization which she founded "American League for Puerto Rico's Independence" came to the defense of Cancel Miranda and the three other Nationalists.[14] Cancel Miranda and the other members of the group were the only defense witnesses, as part of Lebrón's testimony she reaffirmed that they "came to die for the liberty of her homeland".[15][16] On June 16, 1954, the jury declared the four guilty. Holtzoff imposed the maximum imprisonment penalties.[17] On July 13, 1954, the four nationalists were taken to New York, where they declared themselves not guilty on the charges of "trying to overthrow the government of the United States".[18] Among the prosecution's witnesses was Gonzalo Lebrón Jr., who testified against his sister. On October 26, 1954, judge Lawrence E. Walsh found all of the accused guilty of conspiracy, sentencing them to six additional years in prison.[19]

The four Nationalists were incarcerated at different prisons. Figueroa Cordero was sent to the federal penitentiary in Atlanta; Lebrón to the women's prison in Alderson, West Virginia; and Flores Rodríguez to Leavenworth, Kansas, where Oscar Collazo, who in 1950 attacked the Blair House in a failed attempt to assassinate US President Harry S. Truman, was incarcerated. Cancel Miranda, considered to be the primary shooter, received a prison sentence of 85 years and was sent to Alcatraz in the San Francisco Bay.[8]

Imprisonment

Alcatraz

In July 1954, Cancel Miranda, inmate number 1163, was sent to Alcatraz where he served six years of his sentence. Alcatraz Island operated as a Federal Bureau of Prisons federal prison from August 1934 to 1963. While incarcerated, Cancel Miranda worked in the brush factory and served as an altar boy at Catholic services. His closest friends were fellow Puerto Ricans Emérito Vázquez and Hiram Crespo-Crespo. On the recreation yard, he played chess with Harlem gangster Ellsworth "Bumpy" Johnson.[20] He also befriended Morton Sobell, an American convicted of espionage; they remained friends until Sobell's death in December 2018.[20]

During visitation, Cancel Miranda was not allowed to see his children. His wife was allowed to see him in the visiting room, where there was a glass partition, and they could talk using a phone, but were not allowed to speak in Spanish.[8] Due to Cancel Miranda's good behavior in prison, he was transferred to USP Leavenworth in 1960.[20]

Leavenworth

Cancel Miranda spent 10 years in Leavenworth. In 1970, he, Andrés Figueroa Cordero (he was transferred from the federal penitentiary in Atlanta), Irvin Flores Rodríguez and Oscar Collazo organized a prisoners' strike to protest their treatment by the guards. Cancel Miranda was charged with organizing the strike and sentenced to solitary confinement for five months. His wife, who had traveled to visit him during that time, was allowed to see him for one hour. During his imprisonment, in Leavenworth, a photo from a local newspaper reminded him of one of his Cuban experiences, which allowed him to recognize that a genuine revolution was taking place in that country.[10]

Marion

Cancel Miranda was transferred to the Marion Penitentiary, a Federal Bureau of Prisons facility located in Southern Precinct, unincorporated Williamson County, Illinois. By the late 1960s, there were increasing numbers of prisoners engaged in political activity, and Cancel Miranda joined them.

In prison, he read books on sociology and learned to play the guitar. He also became involved in the defense of Corky Gonzales and the "Crusade for Justice". Every September 16, Cancel Miranda would join the Mexican and Chicano prisoners in marking Mexico's independence day with a work stoppage. He was also involved in the African-American struggle.[8] Together they produced newspapers like the Chicano prisoners' paper Aztlán and the Militant. In 1972, he was placed in the Control Unit, where he was held for eighteen months, after a big strike in Marion.[2] In the early years there was no campaign for the release of the Nationalist prisoners. An Afro-American prisoner named Ed Johnson wrote to Michael Deutsch, a lawyer, and invited him to visit the Control Unit. The campaign for the release of the Nationalists began with Michael Deutsch and Mara Siegel from the People's Law Office.

When Cancel Miranda's father died in 1977, his supporters campaigned to allow him to attend the funeral. He was eventually granted a seven-hour furlough in Puerto Rico to attend the funeral.[8][20]

Pardon and later years

In 1979, President Jimmy Carter commuted the sentence of Cancel Miranda, Lolita Lebrón and Irving Flores Rodríguez after they had served 25 years in prison.[21] Andrés Figueroa Cordero was released from prison earlier because of ill health. Governor of Puerto Rico Carlos Romero Barceló publicly opposed the commutations, arguing that it would encourage terrorism and undermine public safety. Cancel Miranda and the other Nationalists received a hero's welcome upon their return to Puerto Rico.[22]

President Carter also commuted the sentence of fellow nationalist Oscar Collazo, to time served on September 6, 1979, after spending 29 years in jail. Collazo had been eligible for parole since April 1966, and Lebrón since July 1969. Both Cancel Miranda and Flores Rodríguez became eligible for parole in July 1979. However, none had applied for parole because of their political beliefs.[23]

| External audio | |

|---|---|

Cancel Miranda authored nine books and remained active in the struggle for Puerto Rican independence. He continued to carry the cause of independence to other countries and returned occasionally to the United States on speaking tours on behalf of Puerto Rican political prisoners. In 1979, at the International Conference in Support of Independence for Puerto Rico, held in Mexico City, Cancel Miranda. Irvin Flores Rodríguez, Lolita Lebrón, and Oscar Collazo were recognized as the embodiment of the directive of their teacher Albizu Campos to exercise valor and sacrifice before representatives of fifty-one countries.[2]

That same year Cancel Miranda was awarded the Order of Playa Girón.[24] The Order of Playa Girón is a national order conferred by the Council of State of Cuba on Cubans or foreigners. In 2006, he was awarded the Order of José Martí by the Cuban government for his work. It is the highest honor Cuba accords to non-Cubans.[20]

A musical production of his poetry, "Por Las Calles de Mi Patria", was well received in Puerto Rico and the rest of the United States. The poems are those he had sent to his father while in prison. He had thought them lost and was surprised to find them published by his father. The musical production is dedicated to those active in the struggle for independence.[2]

Oscar López Rivera founded the Rafael Cancel Miranda High School in Chicago in his honor. The school is now known as the Dr. Pedro Albizu Campos High School and the Juan Antonio Corretjer Puerto Rican Cultural Center.[25]

He died in San Juan, Puerto Rico on March 2, 2020.

Further reading

- "Puerto Rico: Independence Is a Necessity" by Rafael Cancel Miranda (Author); Publisher: Pathfinder Press (NY); Booklet edition (February 1, 2001); ISBN 978-0-87348-895-2

- "Commemorate El Grito de Lares with Rafael Cancel Miranda" by Puerto Rican Socialist Party (Author); ASIN: B0041V1C6U

- "Sembrando Patria...Y Verdades" by Rafael Cancel Miranda (Author); Publisher: Cuarto Idearo (January 1, 1998); ASIN: B001CK17D6

- "Testimonio: Los indómitos [Paperback]" by Antonio Gil de Lamadrid Navarro; Publisher: Editorial Edil,

- "War Against All Puerto Ricans: Revolution and Terror in America's Colony" by Nelson Antonio Denis; Publisher: Nation Books (April 7, 2015); ISBN 978-1568585017.

See also

References

- "Commutations Granted by President Jimmy Carter (1977 - 1981)". December 8, 2017. Archived from the original on January 8, 2021. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- "Rafael Cancel Miranda". www.peacehost.net. Archived from the original on April 19, 2017. Retrieved December 18, 2010.

- Latino Americans and political participation. ABC-CLIO. 2004. ISBN 1-85109-523-3. Archived from the original on January 29, 2022. Retrieved May 1, 2009.

- Insular Police Archived December 14, 2010, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved July 9, 2009.

- "LLMC Book Preservation - Ponce Massacre, Com. of Inquiry, 1937". llmc.com. December 14, 2010. Archived from the original on December 14, 2010. Retrieved July 9, 2009.

- Gov. Winship Responsible for the Massacre Archived December 17, 2010, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved July 9, 2009.

- Biggest Massacre in Puerto Rican History Archived December 17, 2010, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved July 9, 2009.

- "The Militant - 9/21/98 -- 'We Came Out Of Prison Standing, Not On Our Knees' -- Rafael Cancel Miranda on his political activity in jail and the campaign for his freedom". www.themilitant.com. Archived from the original on January 30, 2020. Retrieved March 4, 2020.

- Eustaquio Correa Archived July 13, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- "The Militant - August 14, 2006 -- Puerto Rican independentista Rafael Cancel Miranda on Cuban Revolution". www.themilitant.com. Archived from the original on January 31, 2020. Retrieved March 4, 2020.

- Puerto Rico By Kurt Pitzer, Tara Stevens, page 224, Published by Hunter Publishing, Inc, 2001, ISBN 1-58843-116-9, ISBN 978-1-58843-116-5

- Ribes Tovar et al., p.132

- Ribes Tovar et al., p.178

- "Centropr". www.centropr.org. Archived from the original on June 20, 2010.

- Ribes Tovar et al., p.186

- Ribes Tovar et al., p.188

- Ribes Tovar et al., p.193–194

- Ribes Tovar et al., p.197

- Ribes Tovar et al., p.209

- "Former Alcatraz inmate speaks about his time", Examiner San Francisco, by D. Morita; October 9, 2009

- "Commutations Granted by President Jimmy Carter (1977 - 1981)". U.S. Department of Justice. December 8, 2017. Archived from the original on January 8, 2021. Retrieved January 29, 2022.

- "We Have Nothing to Repent". Time. September 24, 1979. Archived from the original on October 16, 2007. Retrieved July 18, 2008.

- "Jimmy Carter: Puerto Rican Nationalists Announcement of the President's Commutation of Sentences". Archived from the original on May 22, 2011. Retrieved December 18, 2010.

- Arista-Salado, Maikel (2010). Trafford (ed.). Condecoraciones cubanas. Teoría e historia (in Spanish). Trafford. p. 360. ISBN 978-1-4269-4427-7.

- Rosales, Francisco. Dictionary of Latino Civil Rights History. Arte Publico Press, 2006. ISBN 1-55885-347-2. P.159