Radioanalytical chemistry

Radioanalytical chemistry focuses on the analysis of sample for their radionuclide content. Various methods are employed to purify and identify the radioelement of interest through chemical methods and sample measurement techniques.

History

The field of radioanalytical chemistry was originally developed by Marie Curie with contributions by Ernest Rutherford and Frederick Soddy. They developed chemical separation and radiation measurement techniques on terrestrial radioactive substances. During the twenty years that followed 1897 the concepts of radionuclides was born.[1] Since Curie's time, applications of radioanalytical chemistry have proliferated. Modern advances in nuclear and radiochemistry research have allowed practitioners to apply chemistry and nuclear procedures to elucidate nuclear properties and reactions, used radioactive substances as tracers, and measure radionuclides in many different types of samples.[2]

The importance of radioanalytical chemistry spans many fields including chemistry, physics, medicine, pharmacology, biology, ecology, hydrology, geology, forensics, atmospheric sciences, health protection, archeology, and engineering. Applications include: forming and characterizing new elements, determining the age of materials, and creating radioactive reagents for specific tracer use in tissues and organs. The ongoing goal of radioanalytical researchers is to develop more radionuclides and lower concentrations in people and the environment.

Radiation decay modes

Alpha-particle decay

Alpha decay is characterized by the emission of an alpha particle, a 4He nucleus. The mode of this decay causes the parent nucleus to decrease by two protons and two neutrons. This type of decay follows the relation:

Beta-particle decay

Beta decay is characterized by the emission of a neutrino and a negatron which is equivalent to an electron. This process occurs when a nucleus has an excess of neutrons with respect to protons, as compared to the stable isobar. This type of transition converts a neutron into a proton; similarly, a positron is released when a proton is converted into a neutron. These decays follows the relation:

Radiation detection principles

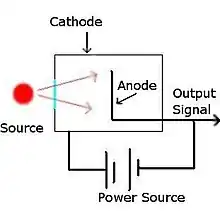

Gas ionization detectors

Gaseous ionization detectors collect and record the electrons freed from gaseous atoms and molecules by the interaction of radiation released by the source. A voltage potential is applied between two electrodes within a sealed system. Since the gaseous atoms are ionized after they interact with radiation they are attracted to the anode which produces a signal. It is important to vary the applied voltage such that the response falls within a critical proportional range.

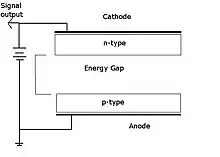

Solid-state detectors

The operating principle of Semiconductor detectors is similar to gas ionization detectors: except that instead of ionization of gas atoms, free electrons and holes are produced which create a signal at the electrodes. The advantage of solid state detectors is the greater resolution of the resultant energy spectrum. Usually NaI(Tl) detectors are used; for more precise applications Ge(Li) and Si(Li) detectors have been developed. For extra sensitive measurements high-pure germanium detectors are used under a liquid nitrogen environment.[6]

Scintillation detectors

Scintillation detectors uses a photo luminescent source (such as ZnS) which interacts with radiation. When a radioactive particle decays and strikes the photo luminescent material a photon is released. This photon is multiplied in a photomultiplier tube which converts light into an electrical signal. This signal is then processed and converted into a channel. By comparing the number of counts to the energy level (typically in keV or MeV) the type of decay can be determined.

Chemical separation techniques

Due to radioactive nucleotides have similar properties to their stable, inactive, counterparts similar analytical chemistry separation techniques can be used. These separation methods include precipitation, Ion Exchange, Liquid Liquid extraction, Solid Phase extraction, Distillation, and Electrodeposition.

Radioanalytical chemistry principles

Sample loss by radiocolloidal behaviour

Samples with very low concentrations are difficult to measure accurately due to the radioactive atoms unexpectedly depositing on surfaces. Sample loss at trace levels may be due to adhesion to container walls and filter surface sites by ionic or electrostatic adsorption, as well as metal foils and glass slides. Sample loss is an ever present concern, especially at the beginning of the analysis path where sequential steps may compound these losses.

Various solutions are known to circumvent these losses which include adding an inactive carrier or adding a tracer. Research has also shown that pretreatment of glassware and plastic surfaces can reduce radionuclide sorption by saturating the sites.[7]

Carrier or tracer addition

Since small amounts of radionuclides are typically being analyzed, the mechanics of manipulating tiny quantities is challenging. This problem is classically addressed by the use of carrier ions. Thus, carrier addition involves the addition of a known mass of stable ion to radionuclide-containing sample solution. The carrier is of the identical element but is non-radioactive. The carrier and the radionuclide of interest have identical chemical properties. Typically the amount of carrier added is conventionally selected for the ease of weighing such that the accuracy of the resultant weight is within 1%. For alpha particles, special techniques must be applied to obtain the required thin sample sources. The use of carries was heavily used by Marie Curie and was employed in the first demonstration of nuclear fission.[8]

Isotope dilution is the reverse of tracer addition. It involves the addition of a known (small) amount of radionuclide to the sample that contains a known stable element. This additive is the "tracer." It is added at the start of the analysis procedure. After the final measurements are recorded, sample loss can be determined quantitatively. This procedure avoids the need for any quantitative recovery, greatly simplifying the analytical process.

Typical radionuclides of interest

| Element | Mass | Half-life (years) | Typical source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Helium | 3 | - stable - | Air, water, and biota samples for bioassays |

| Carbon | 14 | 5,730 | Radiocarbon dating of organic matter, water |

| Iron | 55 | 2.7 | Produced in iron and steel casings, vessels, or supports for nuclear weapons and reactors |

| Strontium | 90 | 28.8 | Common fission product |

| Technetium | 99 | 214,000 | Common fission product |

| Iodine | 129 | 15.7 million | Groundwater tracer |

| Cesium | 137 | 30.2 | Nuclear weapons and nuclear reactors (accidents) |

| Promethium | 147 | 2.62 | Naturally occurring fission product |

| Radon | 226 | 1,600 | Rain and groundwater, atmosphere |

| Uranium | 232, 233, 234, 235, 236, 238 | Varies | Terrestrial element |

| Plutonium | 238, 239, 240, 241, 242 | Varies | Nuclear weapons and reactors |

| Americium | 241 | 433 | Result of neutron interactions with uranium and plutonium |

Quality assurance

As this is an analytical chemistry technique quality control is an important factor to maintain. A laboratory must produce trustworthy results. This can be accomplished by a laboratories continual effort to maintain instrument calibration, measurement reproducibility, and applicability of analytical methods.[9] In all laboratories there must be a quality assurance plan. This plan describes the quality system and procedures in place to obtain consistent results. Such results must be authentic, appropriately documented, and technically defensible."[10] Such elements of quality assurance include organization, personnel training, laboratory operating procedures, procurement documents, chain of custody records, standard certificates, analytical records, standard procedures, QC sample analysis program and results, instrument testing and maintenance records, results of performance demonstration projects, results of data assessment, audit reports, and record retention policies.

The cost of quality assurance is continually on the rise but the benefits far outweigh this cost. The average quality assurance workload was risen from 10% to a modern load of 20-30%. This heightened focus on quality assurance ensures that quality measurements that are reliable are achieved. The cost of failure far outweighs the cost of prevention and appraisal. Finally, results must be scientifically defensible by adhering to stringent regulations in the event of a lawsuit.

References

- Ehmann, W.D., Vance, D. E. Radiochemistry and Nuclear Methods of Analysis, 1991, 1-20

- Krane, K.S. Introductory Nuclear Physics, 1988, John Wiley & Sons, 3-4.

- "Decay equations". Archived from the original on 2009-08-06. Retrieved 2009-07-11.

- "ChemTeam: Writing Alpha and Beta Equations". chemteam.info.

- Loveland, W., Morrissey, D. J., Seaborg, G. T., Modern Nuclear Chemistry, 2006, John Wiley & Sons, 221.

- Ehmann, W.D., Vance, D. E. Radiochemistry and Nuclear Methods of Analysis, 1991, 220-236.

- Theirs, R. E., Separation, Concentration, and Contamination in Trace Analysis, 1957, John Wiley, 637-666.

- O. Hahn & F. Strassmann (1939). "Über den Nachweis und das Verhalten der bei der Bestrahlung des Urans mittels Neutronen entstehenden Erdalkalimetalle ("On the detection and characteristics of the alkaline earth metals formed by irradiation of uranium with neutrons")". Naturwissenschaften. 27 (1): 11–15. Bibcode:1939NW.....27...11H. doi:10.1007/BF01488241. S2CID 5920336..

- Khan, B. Radioanalytical Chemistry, 2007, Springer, 220-243.

- EPA. US Environmental Protection Agency Report 402-R-97-016, 2000, QA/G-4

Further reading

- Chemical Analysis by Nuclear Methods, by Z.B. Alfassi

- Radioanalytical chemistry by J. Tölgyessy, & M. Kyrš.

- Nuclear analytical chemistry by J. Tölgyessy, Š. Varga and V. Kriváň. English translation: P. Tkáč.