Qarinvand dynasty

The Qarinvand dynasty (also spelled Karenvand and Qarenvand), or simply the Karenids, was an Iranian dynasty that ruled in parts of Tabaristan (Mazandaran) in what is now northern Iran from the 550s until the 11th-century. They considered themselves as the inheritors of the Dabuyid dynasty, and were known by their titles of Gilgilan and Ispahbadh. They were descended from Sukhra, a Parthian nobleman from the House of Karen, who was the de facto ruler of the Sasanian Empire from 484 to 493. The Qarinvand dynasty is also considered to be the one of the last Zoroastrian dynasties before the rise of the Islamic Iranian dynasties

Qarinvand dynasty | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 550s–11th-century | |||||||

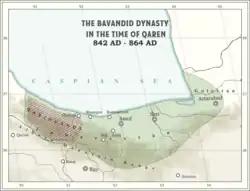

Map shows Qarinvands region during the Qarin I of Bavands. | |||||||

| Capital | Lafur | ||||||

| Common languages | Persian Caspian languages | ||||||

| Religion | Zoroastrianism Islam | ||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||

| Ispahbadh | |||||||

• mid 6th-century | Karin | ||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | ||||||

• Established | 550s | ||||||

• Disestablished | 11th-century | ||||||

| |||||||

| History of Iran |

|---|

|

|

Timeline |

History

The dynasty was founded by Karen, who in return for aiding the Sasanian king Khosrow I (r. 531–579) against the Turks, received land to the south of Amol in Tabaristan. During the 7th century, an unnamed ruler from the Qarinvand dynasty was granted parts of Tabaristan by the Dabuyids who ruled in the area. In 760, the Dabuyid ruler Khurshid was defeated, his dynasty abolished and Tabaristan annexed by the Abbasids, but the Qarinvand and other minor local dynasties continued in existence. At this time, a certain Vindadhhurmuzd is mentioned as the Qarinvand ruler, while his younger brother Vindaspagan ruled as a subordinate ruler over the western Qarinvand regions, which reached as far as Dailam,[1] a region controlled by the Dailamites, who like the Qarinvands and other rulers of Tabaristan were Zoroastrians.

Vindadhhurmuzd, along with the Bavandid ruler Sharwin I, led the native resistance to Muslim rule and the efforts at Islamization and settlement begun by the Abbasid governor, Khalid ibn Barmak (768–772). Following his departure, the native princes destroyed the towns he had built in the highlands, and although in 781 they affirmed loyalty to the Caliphate, in 782 they launched a general anti-Muslim revolt that was not suppressed until 785, when Sa'id al-Harashi led 40,000 troops into the region.[2] Relations with the caliphal governors in the lowlands improved thereafter, but the Qarinvand and Bavandid princes remained united in their opposition to Muslim penetration of the highlands, to the extent that they prohibited even the burial of Muslims there. Isolated acts of defiance like the murder of a tax collector occurred, but when the two princes were summoned before Harun al-Rashid in 805 they promised loyalty and the payment of a tax, and were forced to leave their sons behind as hostages for four years.[3]

Vindadhhurmuzd later died in 815, and was succeeded by his son Qarin ibn Vindadhhurmuzd, who along with Sharwin's successor Shahriyar I was requested by the Abbasid caliph al-Ma'mun to aid in the Arab–Byzantine wars. Shahriyar declined the request, while Qarin accepted, and became successful in his campaign against the Byzantines.[4] Qarin was then bestowed with many honors by Al-Ma'mun. Shahriyar, jealous of Qarin's fame, began annexing some of the latter's territory. In 817, during the reign of Qarin's son Mazyar, Shahriyar, with the aid of Mazyar's uncle Vinda-Umid, expelled the latter from Tabaristan, and seized all his territories.[4]

Mazyar fled to the court of al-Ma'mun, became a Muslim and in 822/23 returned with the support of the Abbasid governor to exact revenge: Shahriyar's son and successor, Shapur, was defeated and killed, and Mazyar united the highlands under his own rule. His growing power brought him into conflict with the Muslim settlers at Amul, but he was able to take the city and receive acknowledgement of his rule over all of Tabaristan from the caliphal court. Eventually, however, he quarreled with Abdallah ibn Tahir, and in 839, he was captured by the Tahirids, who now took over control of Tabaristan.[5] The Bavandids exploited the opportunity to regain their ancestral lands: Shapur's brother, Qarin I, assisted the Tahirids against Mazyar, and was rewarded with his brother's lands and royal title.

Quhyar, a brother of Mazyar, who had betrayed the latter and chose to aid the Tahirids, who promised him the Qarinvand throne, shortly ascended the Qarivand throne, but was shortly killed by his own Dailamite soldiers because of his betrayal against his brother. Although many scholars considered the death of Quhyar as the fall of the Qarinvand dynasty, the dynasty continued to rule in parts of Tabaristan, and a certain Baduspan ibn Gurdzad is mentioned in 864 as the ruler of the Qarinvand dynasty, and is known to have supported the Alid Hasan ibn Zayd. However, his son and successor Shahriyar ibn Baduspan was hostile to Hasan ibn Zayd, but was along with the Bavandid ruler Rustam I forced to acknowledge his authority.[6] Shahriyar's son Muhammad ibn Shahriyar is later mentioned as the later of the Qarivand dynasty in 917, and was like his father hostile to the Alids.[7] Two centuries later, a certain Qarinvand ruler named Amir Mahdi is mentioned in 1106 as one of the vassals of the Bavandid ruler Shahriyar IV. After him, no other Qarinvand ruler is known, but they continued to rule until the 11th-century.[5]

Known Qarinvand rulers

- Karin (550s-?)

- Vindadhhurmuzd (765–815)

- Qarin ibn Vindadhhurmuzd (815–817)

- Mazyar (817–839)

- Quhyar (839)

- Baduspan ibn Gurdzad (mentioned in 864)

- Shahriyar ibn Baduspan (mentioned in 914)

- Muhammad ibn Shahriyar (mentioned in 917)

- Amir Mahdi (mentioned in 1106)

References

- Madelung 1975, p. 201.

- Madelung 1975, p. 202.

- Madelung 1975, pp. 202, 204.

- Ibn Isfandiyar 1905, pp. 145–156.

- Madelung 1975, pp. 204–205.

- Madelung 1975, p. 209.

- Madelung 1975, p. 210.

Sources

- Bosworth, C. E. (1968). "The Political and Dynastic History of the Iranian World (A.D. 1000–1217)". In Boyle, John Andrew (ed.). The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 5: The Saljuq and Mongol Periods. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–202. ISBN 0-521-06936-X.

- Frye, R. N. (1960). "Bāwand". In Gibb, H. A. R.; Kramers, J. H.; Lévi-Provençal, E.; Schacht, J.; Lewis, B. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam. Volume I: A–B (2nd ed.). Leiden: E. J. Brill. p. 1110. OCLC 495469456.

- Madelung, W. (1975). "The Minor Dynasties of Northern Iran". In Frye, Richard N. (ed.). The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 4: From the Arab Invasion to the Saljuqs. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 198–249. ISBN 0-521-20093-8.

- Madelung, W. (1984). "ĀL-E BĀVAND (BAVANDIDS)". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. I, Fasc. 7. London u.a.: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 747–753. ISBN 90-04-08114-3.

- Rekaya, M. (1978). "Ḳārinids". In van Donzel, E.; Lewis, B.; Pellat, Ch. & Bosworth, C. E. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam. Volume IV: Iran–Kha (2nd ed.). Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 644–647. OCLC 758278456.

- Mottahedeh, Roy (1975). "The ʿAbbāsid Caliphate in Iran". In Frye, Richard N. (ed.). The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 4: From the Arab Invasion to the Saljuqs. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 57–90. ISBN 0-521-20093-8.

- Ibn Isfandiyar, Muhammad ibn al-Hasan (1905). An Abridged Translation of the History of Tabaristan, Compiled About A.H. 613 (A.D. 1216). Translated by Edward G. Browne. Leyden: E.J. Brill.