Puget Sound mosquito fleet

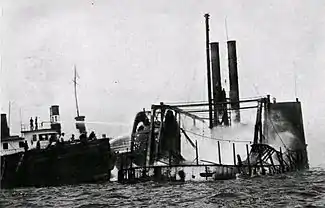

The Puget Sound mosquito fleet was a multitude of private transportation companies running smaller passenger and freight boats on Puget Sound and nearby waterways and rivers. This large group of steamers and sternwheelers plied the waters of Puget Sound, stopping at every waterfront dock. The historical period defining the beginning and end of the mosquito fleet is ambiguous, but the peak of activity occurred between the First and Second World Wars.[1]

Beginnings

Puget Sound and the many adjacent waterways, inlets, and bays form a natural transportation route for much of the western part of Washington. For navigation purposes, Puget Sound was sometimes divided into the "upper Sound" referring to the waters south of the Tacoma Narrows, and the lower sound, referring to the waters from the Tacoma Narrows north to Admiralty Inlet.

The first steamboat to operate on Puget Sound was the Beaver, starting in the late 1830s. Beaver was a sidewheeler built in London, which reached the Northwest under sail, with her paddle wheels dismantled. In 1853, Hudson’s Bay Company brought a new steam-powered vessel into the area, the Otter, a propeller-driven bark.[2]: 6–9

The Native Americans traversed Puget Sound in well-built cedar canoes, as they had for thousands of years, and for some time so did the American settlers, who only began to arrive in very small numbers in 1846. In 1851, Olympia became the only formal American town on Puget Sound. In November 1851, the schooner Exact disembarked passengers at Alki Point, which was the beginning of the city of Seattle. In February 1852, three of the settlers, Arthur A. Denny, C.D. Boren, and William N. Bell, took soundings on the east side of Elliott Bay, found the water to be deep enough near the shore to form a port, and staked land claims along the water.[3]: 1–2

The first American steamboat on Puget Sound was the sidewheeler Fairy built in San Francisco in 1852. Captain Warren Gove, born in Edgecomb, Maine, in 1816[4] (one of three Gove brothers involved in early maritime affairs) brought Fairy to Puget Sound on the deck of the bark Sarah Warren and lowered her into the sound on October 31, 1853. Fairy was the first steamboat on Puget Sound to have a formal schedule, published for the first time on November 12, 1853, in the Columbian newspaper of Olympia. The "splendid steamer" Fairy, as she was advertised, was supposed to make two trips a week between Olympia and Steilacoom, and one trip a week from Olympia to Seattle. Fares were high, $5 for Olympia-Steilacoom, and $10 for Olympia-Seattle. Fairy, however, proved unseaworthy in the rougher winter weather in the lower sound, and after a few runs from Olympia to the then small village of Seattle was eventually replaced by a sailing schooner, which ran irregularly and, more predictably, by mail and passenger canoes. These were owned and crewed by the First Nations. In those days, at least two days and often three were needed to make the trip from Seattle to Olympia, and travellers camped on the beach at night.[3]: 4–5 (Following her failure on the upper sound, Fairy was placed on the much shorter Olympia-Fort Steilacoom run, until 1857, when her boiler exploded. No one was killed, but that was the end of her.[2]: 10–11 )

The next steamboat on the Sound was the Major Tompkins, which arrived on September 16, 1854. Tompkins (151 tons and 97 ft or 29.57 m long) was an iron-hulled steamer with a propeller, built at Philadelphia in 1847, and somehow brought around South America to California, where she had collected gold from gold seekers during the great California gold rush. Paid off by her California competitors in a typical monopolistic deal of the era, Major Tomkins was sitting idle at the dock in San Francisco in 1854 when she was bought by Capt. James M. Hunt and John M. Scranton, who brought her north to Puget Sound. Once she arrived, the Pumpkins, as the locals called her, made her very slow way (about 5 miles per hour) among Olympia, Seattle, Victoria, and other places, carrying mail, freight, and passengers. Pumpkins was lost at Victoria, blown ashore in a squall following a mistake in navigation; all aboard reached safety in a narrow escape.[2]: 11–12 [3]: 6–11

Effect of Fraser River Gold Rush

Other boats were brought in during these early times, including Traveler, Constitution, the diminutive Water Lily, Daniel Webster, Sea Bird, and the steeple-engined Wilson G. Hunt, none of them succeeding particularly well until the Fraser River Gold Rush in 1858. Puget Sound then became a shipping point for supplies and goldseekers, and the steamboats profited well.[2]: 12–16 Bellingham Bay was one jumping-off point for the rush, which was handicapped by the almost complete lack of roads or paths into the mainland of British Columbia at the time, and boats were also brought in to carry miners from Victoria to the mainland, and thereafter up the Fraser River.[5]: 38–52

Rise of steam navigation

In the 1860s and the 1870s, many new steamboats, most built of wood, were brought into the area or built. One of the earliest, and most famous, boats was the sidewheeler Eliza Anderson. Her owners equipped Eliza Anderson with a steam calliope which blasted out a variety of tunes, including (to the irritation of Canadians when she operated north of the border) "Yankee Doodle" and "Star Spangled Banner".[2]: 22–52 Other boats began to appear, and by 1864, J.B. Libby, Mary Woodruff, Pioneer, Alexandra, and Jenny Jones had all appeared on the sound. Steamboat operations were still irregular and unsatisfactory to the general public, as shown by a newspaper commentary of the day:

It has been generally supposed by everybody that steamboating on this Sound was an unprofitable business, and that without mail subsidies and such like emoluments it was scarcely possible for even a single steamer to make weekly trips and pay expenses. ... We do know, however, that several steamers, large and small, are constantly plying the Sound, and even with their annoying irregularity and the competition among them, they manage to keep afloat, continue in trade, and the owners of some evince a degree of disrespect for popular favor very indicative of plenty of business and fat purses. ... The arrivals and departures of steamers at both ends of the route, as well as way ports, seem especially arranged to discomfort, rather than accommodate the public. Steamers come and go like a thief in the night, and no man knows the day or the hour. After spending a whole week of sleepless nights, waiting and watching for boats, passengers frequently have to make two-forty time, in their stockings and nightcaps, to reach the landings before the steamer shoves out. Though they take a whole week to make a twenty-four-hour voyage, they hurry in and out of a way port as if the devil or a sheriff was after them, and the people generally are beginning to indulge the hope that one or the other of those persons may speedily catch and keep them.[6][5]: 16–17

In April 1866, the sidewheeler Cyrus Walker arrived in the sound under Capt. A.B. Gove. Seattle residents, predominantly male and apparently hard-drinking, mistook her for the promised ship full of brides that Asa Mercer was supposed to be bringing from the east coast. Supposedly a tug, Cyrus Walker also carried freight and passengers; in those days on the sound, no firm distinction was necessarily drawn between steam tugs and other steam-driven craft. Eliza Anderson was still dominating the main route on the sound at the time, which was the Olympia to Victoria run. Slow but cheap to operate, the Eliza bested all competitors, including Josie McNear, New World, and the oddly designed (as a result of her steeple engine) Wilson G. Hunt[5]: 21–23

Boom time

The Eliza's monopoly on the main route was broken in 1869, when first she was taken off the main route. Her owners led by Captain Finch, replaced her with the newer Olympia. To make matters worse, the mail contract which had sustained Eliza was awarded to a firm of upstart competitors, led first by Captain Nash, and then by his financiers the Starrs, who had found the cash to buy the Varuna and build the sidewheeler Alida and the propeller Tacoma in the water. A fare war broke out, and on June 23, 1871, the Starrs brought into Puget Sound the then-new sidewheeler North Pacific to run against the Olympia. When North Pacific proved faster than Eliza, the fare war was ended with the customary anticompetitive agreement, whereby the Starrs would pay Finch for keeping the Eliza and Olympia at the dock. Captain Geo. E. Starr died in 1876, but his company survived him, and built in 1879 the sidewheeler George E. Starr named in his honor.[3]: 28–33 [5]: 54–75

By the 1880s and 1890s, the population of the Puget Sound region had risen greatly, and steamboat technology had also improved. Many new and fast vessels were launched, such as the sternwheelers Greyhound and Bailey Gatzert and the famous propeller steamer Flyer. Roads were still poor, and of course as yet no automobiles. The water route was the preferred way to travel between the cities on the sound. In 1890, for example, regular daily service began between Tacoma and Seattle with the Greyhound. In the early 1900s, larger and more durable steel-hulled boats were either built at Puget Sound shipyards, like the Tacoma (launched 1913) or brought in from other areas, like Indianapolis, Chippewa. The Tacoma could make the run from Seattle to Tacoma in 77 minutes dock to dock.[2]: 174

Navigation

Over 40 different steamboat routes were on Puget Sound.[7]: 13 While steamboats were shifted from route to route, also a strong tendency existed for vessels to be run on the same route for a long period of time, and in fact many vessels were purpose-built for a particular route. Some of the reasons for this were economic, as high-passenger routes, such as the Seattle-Port Orchard or the Seattle-Tacoma routes might justify one or even several high-speed passenger-only vessels, like Tacoma, Flyer, or Athlon. Others, like the East Pass route of the Virginia V, warranted a mixed-use passenger/freight/mail boat.

One important consideration which will not necessarily be obvious in modern times of radar, GPS, and depth-sounders, is the degree to which navigational skill and experience on a particular route played in making sure each run was completed safely and profitably: the steamboats could not stop running at night or in bad weather. Heavy fog was particularly hazardous, and could come any time of year. Once a steamboat was in a fog bank, a captain would have to reckon very carefully from his experience on the run just where his boat was. With no radar, captains proved remarkably adept at determining their position with echoes from the steamboat's whistle. Sound travels at about 1,080 feet per second in a fog bank, and rounding off to 1,000 feet for safety, that meant that if an echo was heard one second after the whistle blast, the steamboat was 500 feet from shore.[7]: 31–33 The maritime historian Jim Faber well-summarized the degree of detail that an experienced crew could deduce by echo location:

Experienced navigators not only could estimate how far they were from shore, but also could determine their position by the sound of the echo. This, despite the fact that a low shoreline, a high bank, or a gravel beach all return a different sound. Another determinant was the length of the echo. A short echo denoted a narrow island or headland, for most of the whistle continued by on both sides. With only a few seconds' leeway, the navigators also had to decide whether the echo was bouncing from floating logs, buoys – or even a solid fog bank.[8]: 135–36

An experienced captain needed years of navigation on a particular route to be able to safety pilot his boat through a fog bank or a dark, rainy night using this method. This, of course, made it difficult simply to put a new boat on a particular route without a crew with strong local experience.

Selected routes and landings

Olympia

Olympia's main steamboat landing was Percival Dock. In 1910, boats operating from this dock included the then-new gasoline-engined tug Sandman, the Foss launch Lark, and the mail boat Mizpah. The sternwheeler Multnomah also came to Percival Dock on her Seattle-Tacoma-Olympia route.[8]: 84–85

Shelton

The little sternwheeler Willie (67 feet long) was built at Seattle in 1883 for the Samish River service. In 1886, Capt. Ed Gustafson bought her and put her on the Olympia-Shelton route. In 1895, Captain Gustafson replaced her with the City of Shelton, and Willie went north of the border to serve on the Fraser River.

Hood Canal

In 1899, service to Hood Canal from Seattle's Pier 3 (now Pier 54) was effected by the propeller steamer Dode. A typical wooden boat of the mosquito fleet, the 99-foot Dode left Seattle every Tuesday on the run to Kingston, Port Gamble, Seabeck, Brinnon, Holly, Dewatto, Lilliwaup Falls, Hoodsport, and at the end of what must have been a long day, Union City. The next morning, she returned to Seattle on the same route.[8]: 106–07

Safety and shipwrecks

Crew safety

Safety was a constant issue for steamboats. Some vessels, particularly the later steel-hulled ones, had perfect safety records. This was not always true, and the lives of both passengers and crew were often endangered. Many instances of crewmen falling off vessels and drowning occurred. Crew did not wear life preservers, as is now required on all riverine vessels. For example, in the case of the Mizpah, the engineer went on deck, apparently slipped, fell overboard, and was drowned. Another case was that of Captain O.A. Anderson, a Port Townsend pilot who fell from a ladder in rough seas in late December, 1912, when trying to board the steamship Setos from the pilot launch.[9]: 215–16

Fire

A great danger to all wooden boats was fire. One of the worst disasters in all shipping history was the fire in New York harbor of the General Slocum on June 15, 1904, in which more than 1,000 people died. While the General Slocum was a large vessel, similar sized wooden boats were on Puget Sound and the Columbia River (for example, Alaskan, Olympian, and in particular Yosemite, which routinely boarded more than 1,000 passengers), where on a busy day or a crowded excursion such a death toll could have occurred. Hunter, one of the premier historians of steamboats on the Mississippi-Ohio-Missouri river systems, well summarized the causes of fire in wooden steam craft:

Thin floors and partitions, light framing and siding, soft and resinous woods, the whole dried out by sun and wind and impregnated with oil and turpentine from paint, made the superstructure of the steamboat little more than an orderly pile of kindling wood.[10]

The cause of fire can be readily seen when one considers that in the midst of this pile of oil-soaked wood was placed the biggest furnace that could be afforded by the owner, capped with an enormous smokestack to generate the maximum amount of draft for the fire. Added to this was the risk, in the days before electric light, associated with oil and kerosene lanterns and other sources of ignition. Many vessels were destroyed by fire, two examples being Mizpah and Urania.

Collisions

Collisions were also too common, when steamboats continued to operate in fog or night, without radar or other modern navigation aids, and often caused greater loss of life than fire. Unlike fire, which often could be fought until the vessel reached a beach where passengers and crew could evacuate,[11] collisions came suddenly. Where a substantial difference existed between the size or construction of the vessels, such as steel against wooden hull, destruction could be quick. Thus, on the night of November 18, 1906, the small, lightly built passenger steamer Dix (130 tons), designed specifically for the very short run across Elliott Bay from Seattle to Alki Point, collided with the much larger steam schooner Jeanie. The night was clear, and the collision seems to have been caused by an error of the Dix's unlicensed mate, who had the wheel while the captain, consistent with the practice of the day, collected the fares. Though the collision speed was small, Dix was lightly built and top-heavy; she quickly heeled over, filled with water, and sank in 103 fathoms, taking 45 people down with her, including her mate. The wreck was so deep that no bodies could be recovered.[9]: 124 [2]: 142–144 Similarly, but less tragically, the wooden sternwheeler Multnomah was rammed (also in Elliott Bay, the scene of much marine traffic) by the much larger, steel-hulled, express passenger Iroquois on October 28, 1911, sinking Multnomah in 240 feet of water, but with no one killed.[9]: 197

Loss of the Clallam

By 1904, the causes of shipping losses were well-known and safety measures had been established by law, and enforced by the U. S. Steamboat Inspection Service. Each vessel's certificate stated how many lifeboats, fire axes, and similar items were supposed to be carried. Yet, that year had the tragic loss of life on the Clallam, which left Seattle bound for Victoria on January 8, 1904, under the command of Capt. George Roberts. A storm came up as she neared Victoria, and she started taking on water. When her pumps failed (apparently they brought water into the vessel rather than evacuating it), her boiler fire was extinguished by the rising water, and she lost all power, save for an emergency sail. The captain ordered three lifeboats launched, and put into them the women and children, yet no ship’s officers went on board to command the boats in the rough seas. All three boats were lost with all the passengers on them. Clallam stayed afloat long enough to be found by rescuers, but even so, 54 people died. Serious ship handling and mechanical defects seemed to have caused the loss of the Clallam, and the license of her master, George Roberts, a 29-year veteran steamboat man, was suspended, and that of her chief engineer was revoked.[9]: 100 [7]: 68–71 The supply of signalling rockets also seemed to be insufficient.[2]: 144

Crackdown by steamboat inspectors

Following the Clallam disaster, a crackdown on violations of the steamboat safety regulations began, which seems to have been widely ignored. At Port Townsend, following a surprise inspection of the steamer Garland on February 6, 1904, these defects were found:

- No relieving tackle on the tiller (this was necessary to steer the vessel in case of wheel failure or loss of the main steering ropes through fire)

- No ladders or stairways to the hurricane deck where the fire buckets and lifeboats were kept

- Fewer fire buckets than required by the vessel’s certificate, and no water in many of what fire buckets were on board

- Fewer fire axes than required by her certificate

- Life raft had no designation on it of the number of persons it was supposed to carry in an emergency

- Lifeboats and launching gear are generally in poor condition

Similar conditions were found on the same day on the Prosper, and to a lesser degree on the Alice Gertude and the Whatcom, although they were referred for special boiler inspections.[12] The inspections and fines assessed on these four vessels were just part of a campaign by the inspectors to enforce the regulations on all steam craft operating in Puget Sound. By February 17, 1904, 16 more vessels, including some well-known ones, had been inspected, found deficient, and fined for similar reasons, and in addition failure to maintain adequate fog horns and not providing sufficient written instructions to passengers as to the location of life preservers. Vessels found deficient included the well-known George E. Starr, Rosalie, and Athlon.[13]

All of the many defects found by the steamboat inspectors on Puget Sound were typical of the lax standards of the day, which contributed to the horrible death toll in the loss by fire of the General Slocum. This loss, which occurred while the General Slocum was packed with a crowd for an excursion, produced swift results on Puget Sound, as inspectors strictly counted the total numbers of persons boarded on each vessel, and gave notice that remissions of fines for equipment defects would be no more. (By custom, heavy fines imposed on steamboats would be remitted upon a showing of compliance by the vessel's owners.)[14]

Conversion to ferries and decline

As automobile ownership rose and highways and roads improved, passenger travel fell off. Many boats were converted to automobile ferries, the first being the Bailey Gatzert. Others were eventually just abandoned on beaches or never repaired after a wreck or a mechanical breakdown. Some, like the Magnolia, were converted into towboats.[2]: 188 Others had different fates. Arcadia, the last passenger vessel (capacity 275 passengers, 100 tons freight) operating between Tacoma and upper Puget Sound landings under the command of Capt. Bernt Bertson, was sold to the federal government for use as a tender for the federal prison on McNeil Island, where she was renamed J.E. Overlade. This was not the end of Arcadia, however, as in 1959, she was bought back from the federal government by Puget Sound Excursion Lines, renamed Virginia VI, and placed in the excursion business with the Virginia V then under the same ownership.[9]: 509 and 639

Nicknames and popular verse

Steamboats attracted a lot of nicknames, not all of them complimentary. As mentioned, the Tomkins was called the Pumpkins. The Greyhound was called the Hound, the Pup and the Dog.[2]: 3 Wealleale was known to all as Weary Willie.[5]: 156 The Robert Duinsmere, originally as a sidewheel steamer in Canada for the Vancouver-Nanaimo route, was later rebuilt as propeller collier, thereby suffering the misfortune of becoming known as the Dirty Bob.[9]: 111 The City of Shelton, lacking a spray guard over her paddlewheel, was called Old Wet-Butt by crew of the propeller Marian, her competitor on the Olympia-Shelton route.[2]: 153 And in the 1920s, Barely-Gets-There was the appellation for the once-sleek Bailey Gatzert sponsoned-out as she was to carry as many autos as could be loaded on her, and made more ugly yet with the addition of a loading elevator on her foredeck.

The sidewheeler George E. Starr lasted from 1879 to 1911, and slowed down to the point where a song was composed about her:

Paddle, paddle, George E. Starr, How we wonder where you are. Leaves Seattle at half past ten. Gets to Bellingham, God knows when![8]: 96

William J. Fitzgerald, who later became Seattle's fire chief, at age 8 was said to have composed a little tribute to two Seattle pioneers and two famous steamboats as:

Ezra Meeker, just before he died

Said there's just one steamboat I'd like to ride; Joshua Green said what will it be ...

The George E. Starr or the Rosalie?[7]: 42

Final years

A single "last voyage" of the mosquito fleet never occurred, in contrast to the famous last runs of the Georgie Burton in 1947 on the Columbia or the Moyie on Kootenay Lake in 1957. Races were staged up through the 1950s, and a few revivals on a few runs, even as late as the Second World War. By the late 1920s, though, automobiles and highways had filled the transportation needs that steamboats had once supplied, and in 1930, the Tacoma made her last run on the Seattle-Tacoma route, under the command of Captain Everett D. Coffin, the only skipper she had ever had. This marked the real end of commercial passenger activity for the steamboats. Newell and Williamson documented the occasion:

The Tacoma and the Indianapolis passed a little south of Three Tree Point. ... Capt. Coffin pulled down a window and leaned out in the driving rain. The Indianapolis floated by, a dozen squares of light topped by a star. She spoke; three long, lingering blasts. ... Capt. Coffin reached for his own whistle cord. Three long blasts. And he let the last blast die away slowly, until it was only a moan in the throat of the whistle. “That's the last time we pass each other,” he said.[15]

When Tacoma arrived at her dock in Tacoma harbor that last night, every ship in the port blew three blasts on their whistles as a salute. Andrew Foss, the owner of the great Foss tug concern, sent Foss No. 17 to help Tacoma make her landing, though two years had passed since Tacoma could afford the help of a tug. As she left that last time on her return to Seattle, Tacoma passed the hull of the Greyhound, once the fastest boat on the sound and now, minus her upper works, engines, and sternwheel, in her last service as a mudscow.[15]

Legacy

The Washington State Ferries system now runs on many of the routes of the mosquito fleet, of which the fine steamer Virginia V, newly restored, is one of the last remaining vessels. The oldest remaining vessel is the motor vessel Carlisle II, built in Bellingham in 1917 and still in regular revenue service between Bremerton and Port Orchard for Kitsap Transit. Of the other little ships, Gordon Newell, one of their greatest historians, wrote:

The little ships had much of humanity in them. Few had great adventures, for they had their humble, daily tasks to do in their own small world ... from Flattery to Olympia. They worked hard and well, making many friends. They seldom hurt anyone. They managed to keep their particular sort of jaunty, wind-swept beauty until the end.[2]: 191

As a modern reminder of the little ships, in 2001, Kitsap County inventoried all the many landings and docks of the mosquito fleet on Bainbridge Island and the Kitsap Peninsula, and developed the Kitsap County Mosquito Fleet Trail for bicycles and foot traffic.[16] Presently, Kitsap Transit operates a passenger-only ferry between Port Orchard and Bremerton. The Carlisle II has been designated as a floating museum. It is one of few mosquito fleet-era ferries operating on Puget Sound today. It runs every half-hour beginning on the hour and half-hour on the Port Orchard side and 15 and 45 minutes after the hour on the Bremerton side. One-way fare is $2.00.[17]

Return of the mosquito fleet

Occasionally, talk of restoring the mosquito fleet revives, which in modern parlance has become known as the "passenger-only ferry", although apparently not much has come of these ideas, as they seem to be dependent on public funding or subsidies. (Although not necessarily a subsidy, since they were getting paid the going rate for the work, the first mosquito fleet was heavily supported by mail carriage contracts.)[18]

Some movement towards this may be happening. In August 2007, the city of Kingston received a $3.5 million grant from the federal government to cover at least some of the costs of building a terminal and a passenger-only ferry between Kingston and Seattle.[19]

In April 2007, the countywide The King County Ferry District was formed to expand transportation options for county residents through passenger ferry services. The district board is composed of all nine members of the Metropolitan King County Council.[20] On July 1, 2008, the KCFD took over the operations of two existing passenger-ferry services and considered up to five new routes.[21] In 2015 the district was absorbed into the county Department of Transportation.

Kitsap County voted in 2016 to subsidize three passenger ferries to Seattle. One, a low wake catamaran started service in July 2017 with six round trips daily, three in the morning and three in the afternoon. Service from Kingston to downtown Seattle began November 26, 2018 with three round trips each in the morning and afternoon. Previously riders from Kingston arrived in Edmonds and must take ground transportation from Edmonds to Seattle. One more route from Southworth to downtown Seattle began in 2020.[22] These join two other mosquito routes, Bremerton to Port Orchard and Bremerton to Annapolis.

See also

- Boston Harbor, Washington

- List of Puget Sound steamboats

- Seattle tugboats

References

- Jensen, Erv, ed. (1988). Manette Pioneering. Bremerton, Washington: Manette History Club. p. 5.

- Newell, Gordon (1960). Ships of the Inland Sea (2nd ed.). Portland, OR: Binford and Mort.

- Carey, Roland (1962). The Steamboat Landing on Elliott Bay. Seattle, WA: Alderbrook Publishing.

- Gove, William Henry (1922). The Gove Book History and Genealogy of the American Family of Gove. Salem MA.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Carey, Roland (1965). The Sound of Steamers. Seattle, WA: Alderbrook Publishing.

- The Seattle Gazette, August 20, 1864

- Kline, M. S.; Bayless, G. A. (1983). Ferryboats – A Legend on Puget Sound. Seattle, WA: Bayless Books. ISBN 0-914515-00-4.

- Faber, Jim (1985). Steamer's Wake. Seattle, WA: Enetai Press. ISBN 0-9615811-0-7.

- Newell, Gordon R., ed. (1966). H. W. McCurdy Marine History of the Pacific Northwest. Seattle, WA: Superior Publishing.

- Hunter, Louis C. (1949). Steamboats on the Western Rivers. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications. p. 278. ISBN 0-486-27863-8.

- In the General Slocum fire, where more than 1,000 people died, the captain was criticized sharply for continuing on course instead of running his ship ashore

- "Garland and Prosper Assessed Heavy Fines". Port Townsend Morning Leader. February 9, 1904. p. 1.

- "Sixteen Vessels Receive Fines". Port Townsend Morning Leader. February 17, 1904. p. 4.

- "Steamers Being Held to Strict Letter of Law". Port Townsend Morning Leader. June 29, 1904. p. 4.

- Newell, Gordon; Williamson, Joe (1958). Pacific Steamboats. Seattle, WA: Superior Publishing. pp. 130–31.

- "Mosquito Fleet Trail Plan" (PDF). Kitsap County Public Works. Retrieved 2008-05-31.

- "Welcome Aboard Kitsap Transit!". Destination Bremerton Waterfront. Archived from the original on September 9, 2014.

- St. Clair, Tim (July 10, 2007). "Passenger Ferry Fleet Eyed for Puget Sound". West Seattle Herald. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016.

- "Editorial: Renewed Needs for the Mosquito Fleet". Kitsap Sun. November 15, 2007. Retrieved 2008-01-28.

- Constantine, Dow; Hague, Jane (November 29, 2007). "Passenger Ferries: A mobility solution". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on August 23, 2017. Retrieved 2008-05-31.

- "King County Ferry District". Metropolitan King County Council. Archived from the original on March 5, 2008.

- "Fast Ferry". Kitsap Transit. Retrieved 2020-01-27.

Further reading

- Findlay, Jean Cammon and Paterson, Robin, Mosquito Fleet of Southern Puget Sound, (2008) Arcadia Publishing ISBN 0-7385-5607-6

- Gibbs, Jim, and Williamson, Joe, Maritime Memories of Puget Sound, Schiffer Publishing, West Chester, PA 1987, ISBN 0-88740-044-2

- Newell, Gordon, and Williamson, Joe, Pacific Steamboats, Bonanza Books, New York, NY (1963)