Print culture

Print culture embodies all forms of printed text and other printed forms of visual communication. One prominent scholar of print culture in Europe is Elizabeth Eisenstein, who contrasted the print culture of Europe in the centuries after the advent of the Western printing-press to European scribal culture. The invention of woodblock printing in China almost a thousand years prior and then the consequent Chinese invention of moveable type in 1040 had very different consequences for the formation of print culture in Asia. The development of printing, like the development of writing itself, had profound effects on human societies and knowledge. "Print culture" refers to the cultural products of the printing transformation.

In terms of image-based communication, a similar transformation came in Europe from the fifteenth century on with the introduction of the old master print and, slightly later, popular prints, both of which were actually much quicker in reaching the mass of the population than printed text.

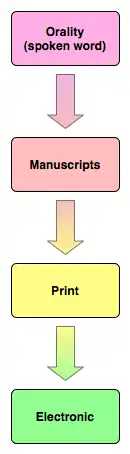

Print culture is the conglomeration of effects on human society that is created by making printed forms of communication. Print culture encompasses many stages as it has evolved in response to technological advances. Print culture can first be studied from the period of time involving the gradual movement from oration to script as it is the basis for print culture. As the printing became commonplace, script became insufficient and printed documents were mass-produced. The era of physical print has had a lasting effect on human culture, but with the advent of digital text, some scholars believe the printed word may become obsolete.

The electronic media, including the World Wide Web, can be seen as an outgrowth of print culture.

The development of print culture

Prior to print

Prior to print, knowledge was transmitted through oral traditions, including formulaic story telling supported by mnemonic techniques,[1][2] as well as architectural and material artifacts.[3] the invention of writing brought with it the emergence of scribal culture. Scholars disagree over when scribal culture developed. Walter Ong argues that scribal culture cannot exist until an alphabet is created, and a form of writing standardized. On the other hand, D. F. McKenzie argues that even communicative notches on a stick, or structure, represent “text”, and therefore scribal culture.

Ong suggests scribal culture is defined by an alphabet. McKenzie says that the key to scribal culture is non-verbal communication, which can be accomplished in more ways than using an alphabet. These two views give rise to the importance of print culture. In scribal culture, procuring documents was a difficult task, and documentation would then be limited to the rich only. Ideas are difficult to spread amongst large groups of people over large distances of land, not allowing for effective dissemination of knowledge.

Scribal culture also deals with large levels of inconsistency. In the process of copying documents, many times the meaning became changed, and the words different. Reliance on the written text of the time was never exceedingly strong. Over time, a greater need for reliable, quickly reproduced, and a relatively inexpensive means of distributing written text arose. Scribal culture, transforming into print culture, was only replicated in manners of written text.

Jack Goody, however, documents that the introduction of written language was transformative for finances, religion, law, and governance. Written language facilitated higher levels of organization, coherence and consistency of messages, extending reach of control, ownership and belief, creating rule of law, critical comparison of statements, among other effects.[4] Extensive scribal cultures with corresponding social consequences emerged in the ancient Middle East,[5] the Ancient Hebrew world, Classic Greece and Rome,[6] India,[7] China,[8][9] Mesoamerica,[10] and the Islamic world.[11] The complexity of cultural change in the ancient Middle East is documented in the Oxford Handbook of Cuneiform Culture.[12]

Development of print

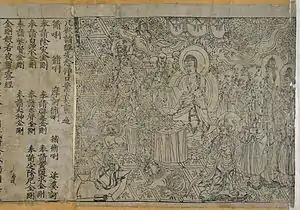

The Chinese invention of paper and woodblock printing, at some point before the first dated book in 868 (the Diamond Sutra) produced the world's first print culture.[13] Hundreds of thousands of books, on subjects ranging from Confucian Classics to science and mathematics, were printed using woodblock printing.[14] Printing was regulated by the state and largely served the interests of the educated bureaucracy.[8][15] Only during the Ming and Qing dynasties did the publication of vernacular texts become common.

Paper and woodblock printing were introduced into Europe in the 15th century, and the first printed books began appearing in Europe. Chinese movable type was spread to Korea during the Goryeo dynasty. Around 1230, Koreans invented a metal type movable printing which was described by the French scholar Henri-Jean Martin as "extremely similar to Gutenberg's".[16] East metal movable type was spread to Europe between the late 14th century and early 15th century.[17][18][19][20] The invention of Johannes Gutenberg's printing press (c. 1450) greatly reduced the amount of labor required to produce a book leading to an increase in the number of books produced. Early printers tried to keep their printed copies of a text as faithful as possible to the original manuscript. Even so, the earliest publications were still often different from the original, for a short time, in some ways manuscripts still remaining more accurate than printed books.

Hand-copied illustrations were replaced by first woodcuts, later engravings that could be duplicated precisely, revolutionizing technical literature.[21]

Print culture, the Renaissance, the Reformation, and Early Modern Science

Eisenstein has described how the high costs of copying scribal works often led to their abandonment and eventual destruction. Furthermore, the cost and time of copying led to the slow propagation of ideas. In contrast, the printing press allowed rapid propagation of ideas, resulting in knowledge and cultural movements that were far harder to destroy. Eisenstein points to prior renaissances (rebirths) of classical learning prior to the printing press that failed. In contrast, the Renaissance was a permanent revival of classical learning because the printing of classical works put them into a permanent and widely read form. Similarly, Eisenstein points to a large number of prior attempts in Western Europe to assert doctrines contrary to the ruling Catholic Church. In contrast, the Protestant Reformation spread rapidly and permanently due to the printing of non-conformist works such as the 95 Theses. Eisenstein equally examined the impact of print on the development of science with the rapid and extensive dissemination of observations and data, the exact reproductions of charts and figures that allowed for comparison, and the impulse towards aggregation taxonomy.[22]

Because of the transformative consequences of the printing press, printing houses such as that of Christophe Moretus in Antwerp (now the Plantin-Moretus Museum) became for a time the center of print culture as authors considered themselves as belonging to a Republic of Letters. To build confidence in the knowledge arising from their presses, publishers fostered communities of trust.[23]

Renaissance

Johannes Gutenberg invention of the moveable type printing press provided a less expensive (though still costly) and more rapid way of filling the demand for books. Despite these advantages, printing had many critics, who were afraid that books could spread lies and subversion or corrupt unsuspecting readers [citation needed]. Also, they [who] were afraid that the printed texts would spread heresy and sow religious discord. The Gutenberg Bible was the first book produced with moveable type in Europe. Martin Luther's Bible, which was published in German in 1522, started the Protestant Reformation. Latin's importance as a language started languishing with the rise of texts written in national languages. The shift from scholarly Latin to everyday languages marked an important turning point in print culture. The vernacular Bibles were important to other nations, as well. The King James Authorized Version was published in 1611, for example. Along with the religious tracts, the scientific revolution was largely due to the printing press and the new print culture. Scholarly books were more accessible, and the printing press provided more accurate diagrams and symbols. Along with scientific texts, like the works of Copernicus, Galileo, and Tycho Brahe, atlases and cartography started taking off within the new print culture, mostly due to the exploration of different nations around the world.[24]

Enlightenment

With the rise of literacy, books and other texts became more entrenched in the culture of the West. Along with literacy and more printed words also came censorship, especially from governments. In France, Voltaire and Rousseau were both imprisoned for their works. Other authors, like Montesquieu and Diderot, had to publish outside France. Censored books became a valuable commodity within this environment, and an underground network of book smugglers started operating within France. Diderot and Jean d'Alembert created the Encyclopedie, which was published in 1751 in seventeen folio volumes with eleven volumes of engravings. This work embodied the essence of the Age of Enlightenment.[25]

Print culture and the American Revolution

A profound impact

Numerous eras throughout history have been defined through the use of print culture. The American Revolution was a major historical conflict fought after print culture brought the rise of literacy. Furthermore, print culture's ability to shape and guide society was a critical component before, during, and after the Revolution.

Pre-Revolution

Many different printed documents influenced the beginning of the revolution. Magna Carta was originally a scribal document of 1215, recording an oral transaction restricting the power of English kings and defining rights of subjects. It was revitalized by being printed in the 16th century and widely read by the increasingly literate English and colonial population thereafter. Magna Carta was used as a basis for the development of English liberties by Sir Edward Coke and became a basis for writing the Declaration of Independence.

Additionally, during the 18th century, the production of printed newspapers in the colonies greatly increased. In 1775, more copies of newspapers were issued in Worcester, Massachusetts than were printed in all of New England in 1754, showing that the existence of the conflict developed a need for print culture. This onslaught of printed text was brought about by the anonymous writings of men such as Benjamin Franklin, who was noted for his many contributions to the newspapers, including the Pennsylvania Gazette. This increase was primarily due to the easing of the government's tight control of the press, and without the existence of a relatively free press, the American Revolution may have never taken place. The production of so many newspapers can mostly be attributed to the fact that newspapers had a huge demand; printing presses were writing the newspapers to complain about the policies of the British government, and how the British government was taking advantage of the colonists.

In 1775, Thomas Paine wrote the pamphlet Common Sense, a pamphlet that introduced many ideas of freedom to the Colonial citizens. Allegedly, half a million copies were produced during the pre-revolution era. This number of pamphlets produced is significant as there were only a few million freed men in the colonies. Common Sense was not the only manuscript that influenced people and the tide of the revolution. Among the most influential were James Otis' "Rights of the British Colonies" and John Dickinson's 1767-68 Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania. Both of these played a key role in persuading the people and igniting the revolution.

During the Revolution

Newspapers were printed during the revolution covering battle reports and propaganda. These reports were usually falsified by Washington in order to keep morale up among American citizens and troops. Washington was not the only one to falsify these reports, as other generals (on both sides) used this technique as well. The newspapers also covered some of the battles in great detail, especially the ones that the American forces won, in order to gain support from other countries in hopes that they would join the American forces in the fight against the British.

Before the Revolution, the British placed multiple acts upon the colonies, such as the stamp act. Many newspaper companies worried that the British would punish them for printing papers without a British seal, so they were forced to temporarily discontinue their work or simply change the title of their paper. However, some patriotic publishers, particularly those in Boston, continued their papers without any alteration of their title.

The Declaration of Independence is a very important written document that was drafted by the Committee of Five and other Founding Fathers representing the original Thirteen Colonies, as a form of print culture that would declare their independence from the Kingdom of Great Britain and explained the justifications for doing so. While it was explicitly documented on July 4, 1776, it was not recognized by Great Britain until September 3, 1783, by the Treaty of Paris.

Post-Revolution

After the signing of the Treaty of Paris, a cluster of free states in need of a government was created. The basis for this government was known as the Articles of Confederation, which were put to effect in 1778 and formed the first governing document of the United States of America. This document, however, was found to be unsuitable to outline the structure of the government, and thus showed an ineffectual use of print culture, and since printed texts were the most respected documents of the time, this called for an alteration in the document used to govern the confederation.

It was the job of the Constitutional Convention to reform the document, but they soon discovered that an entirely new text was needed in its place. The result was the United States Constitution. In the form of written word, the new document was used to grant more power to the central government, by expanding into branches. After it was ratified by all of the states in the union, the Constitution served as a redefinition of the modern government.

Thomas Jefferson was noted as saying, "The basis of our governments being the opinion of the people, the very first object should be to keep that right; and were it left to me to decide whether we should have a government without newspapers, or newspapers without a government, I should not hesitate a moment to prefer the latter."[26] This serves as an excellent example of how newspapers were highly regarded by the colonial people. In fact, much like other forms of 18th century print culture, newspapers played a very important role in the government following the Revolutionary War. Not only were they one of the few methods in the 18th century to voice the opinion of the people, they also allowed for the ideas to be disseminated to a wide audience, a primary goal of printed text. A famous example of the newspaper being used as a medium to convey ideas were The Federalist Papers. These were first published in New York City newspapers in 1788 and pushed for people to accept the idea of the United States Constitution by enumerating 85 different articles that justified its presence, adding to a series of texts designed to reinforce each other, and ultimately serving as a redefinition of the 18th century.

The state of print today

Today, print has matured to a state where the majority of modern society has come to have certain expectations regarding the printed book:

- The knowledge contained by printed books is believed to be accurate.

- The cited author of a printed book does indeed exist and is actually the person who wrote it.

- Every copy of a printed book is identical (at least in the important aspects) to every other copy, no matter how far apart the locations are in which they are sold.

Copyright laws help to protect these standards. However, a few regions do exist in the world where literary piracy has become a standard commercial practice. In such regions, the preceding expectations are not the norm.[27]

Currently, there are still approximately 2.3 billion books still sold each year worldwide. However, this number is steadily decreasing due to the ever-growing popularity of the Internet and other forms of digital media.

Transition to the digital era

As David J. Gunkel states in his article "What's the Matter with Books?", society is currently in the late age of the text; the moment of transition from print to electronic culture where it is too late for printed books and yet too early for electronic texts. Jay David Bolter, author of Writing Space, also discusses our culture in what he calls "the late age of print." The current debate going on in the literary world is whether or not the computer will replace the printed book as the repository and definition of human knowledge. There is still a very large audience committed to printed texts, who are not interested in moving to a digital representation of the repository for human knowledge. Bolter, in his own scholarship and also along with Richard Grusin in Remediation, explains that despite current fears about the end of print, the format will never be erased but only remediated. New forms of technology (new media) will be created which utilize features of old media, thus preventing old media's (aka print's) erasure. At the same time, there are also concerns over whether obsolescence and deterioration make digital media unsuitable for long-term archival purposes. Much of the early paper used for print is highly acidic, and will ultimately destroy itself.

The way that information is transferred has also changed with this new age of digital text and the shift towards electronic media. Gunkel states that information now takes the form of immaterial bits of digital data that are circulated at the speed of light. Consequently, what the printed book states about the exciting new culture and economy of bits is abraded by the fact that this information has been delivered in the slow and outdated form of physical paper.

In the article, "The First Amendment, Print Culture, and the Electronic Environment", the author notes that expectations will change as information becomes less tied to specific locations, and as machines become networked and linked to other machines.[28] This means that in the future certain goods will not be associated with their origins.

The article "The First Amendment, Print Culture, and the Electronic Environment" also mentions how the new electronic age will make print better.[29] Placing information into electronic form not only liberates the information from its pages but removes the need for specialized spaces to hold particular kinds of information. People have become increasingly accustomed to acquiring information from our homes that used to be only accessible from an office or library. Once computers are all networked, all information should, at least in theory, be accessible from all places. Print itself contained a set of invisible and inherent censors, which electronic media is helping to remove from the creation of text. Points of control that are present in print space are no longer present as distribution channels multiply, as copying becomes faster and cheaper, as more information is produced, as economic incentives for working with information increase, and as barriers and boundaries that inhibited working with information are crossed.

Changes in technology and its effect on print culture

There are more online publications, journals, newspapers, magazines, and businesses than ever before. While this brings society closer, and makes publications more convenient and accessible, ordering a product online reduces contact with others. Many online articles are anonymous, making the 'death of the author' even more apparent. Anyone can post articles and journals online anonymously. In effect, the individual becomes separated from the rest of society.

The advances of technology in print culture can be separated into three shifts:

- spoken language to the written word,

- the written word to Printing press,

- the printing press to the computer/internet.

The written word has made history recordable and accurate. The printing press, some may argue, is not a part of print culture, but had a substantial impact upon the development of print culture through the times. The printing press brought uniform copies and efficiency in print. It allowed a person to make a living from writing. Most importantly, it spread print throughout society.

The advances made by technology in print also impact anyone using cell phones, laptops, and personal digital organizers. From novels being delivered via a cell phone, the ability to text message and send letters via e-mail clients, to having entire libraries stored on PDAs, print is being influenced by devices.

Non-textual forms of print culture

Symbols, logos and printed images are forms of printed media that do not rely on text. They are ubiquitous in modern urban life. Analyzing these cultural products is an important part of the field of cultural studies. Print has given rise to a wider distribution of pictures in society in conjunction with the printed word. Incorporation of printed pictures in magazines, newspapers, and books gave printed material a wider mass appeal through the ease of visual communication.

Text and print

There is a common miscommunication that occurs when discussing that which is print and that which is text. In the literary world, notable scholars such as Walter Ong and D. F. McKenzie have disagreed on the meaning of text. The point of the discussion at hand is to have a word that encompasses all forms of communication - that which is printed, that which is online media, even a building or notches on a stick. According to Walter Ong text did not come about until the development of the first alphabet, well after humanity existed. According to Mckenzie primitive humans did have a form of text they used to communicate with their cave drawings. This is discussed in literary theory. Print, however, is a representation of that which is printed, and does not encompass all forms of communication (e.g. a riot at a football game).

See also

Notes

- Albert B. Lord, The singer of tales (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1960).

- Rubin, D. C. (1995). Memory in oral traditions. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

- Renfrew, C., & Scarre, C. (Eds.). (1999). Cognition and material culture: The archaeology of symbolic storage. Cambridge, England: McDonald Institute.

- Goody, J. (1986). The Logic of Writing and the Organization of Society. Cambridge University Press.

- Vanstiphout, H. L. J. (1995). On the old Babylonian Eduba curriculum. In J. W. Drijvers & A. A. MacDonald (Eds.), Centres of learning: Learning and location in pre-modern Europe and the Near East (pp. 3–16). Leiden, Netherlands: Brill.

- Havelock, E. (1982). The literate revolution in Greece and its cultural consequences. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Mookerji, K. R. (1969). Ancient Indian education: Brahmanical and Buddhist. London: Macmillan.

- Connery, C. L. (1998). The empire of the text. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Lee, T. H. C. (2000). Education in traditional China: A history (Handbook of Oriental Studies, Vol. 13). Leiden, Netherlands: Brill.

- Berdan, F. (2005). The Aztecs of central Mexico: An imperial society. Belmont, CA: Thomson Wadsworth.

- Makdisi, G. (1981). The rise of colleges: Institutions of learning in Islam and the West. Edinburgh, Scotland: Edinburgh University Press.

- Radner, K. & Robson, E. (Eds.). (2011). The Oxford Handbook of Cuneiform Culture. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- A Hyatt Mayor, Prints and People, Metropolitan Museum of Art/Princeton, 1971, nos 1-4. ISBN 0-691-00326-2

- Luo, S. (1998). An illustrated history of printing in ancient China. Hong Kong: City University Press.

- Wang, H. (2014). Writing and the ancient state: Early China in comparative perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Briggs, Asa and Burke, Peter (2002) A Social History of the Media: from Gutenberg to the Internet, Polity, Cambridge, pp.15-23, 61-73.

- Polenz, Peter von. (1991). Deutsche Sprachgeschichte vom Spätmittelalter bis zur Gegenwart: I. Einführung, Grundbegriffe, Deutsch in der frühbürgerlichen Zeit (in German). New York/Berlin: Gruyter, Walter de GmbH.

- Thomas Christensen (2007). "Did East Asian Printing Traditions Influence the European Renaissance?". Arts of Asia Magazine (to appear). Retrieved 2006-10-18.

- Thomas Franklin Carter, The Invention of Printing in China and its Spread Westward, The Ronald Press, NY 2nd ed. 1955, pp. 176–178

- L. S. Stavrianos (1998) [1970]. A Global History: From Prehistory to the 21st Century (7th ed.). Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-923897-0.

- Eisenstein 155

- Eisenstein, E. L. (1979). The printing press as an agent of change. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- Johns, A. (1998). The nature of the book: Print and knowledge in the making. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Lyons, Martyn. Books: A Living History. Paul Getty Museum, 2011. Chapter 2.

- Lyons, Martyn. Books: A Living History. Paul Getty Museum, 2011. Chapter 3.

- "Amendment I (Speech and Press): Thomas Jefferson to Edward Carrington". press-pubs.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 2023-07-30.

- Johns 61

- "The First Amendment, Print Culture, and the Electronic Environment". www-unix.oit.umass.edu. Archived from the original on 2006-06-19.

- "The First Amendment, Print Culture, and the Electronic Environment". www-unix.oit.umass.edu. Archived from the original on 2006-06-19.

References

- Eisenstein, Elizabeth The Printing Revolution in Early Modern Europe

- Eisenstein, Elizabeth. “Defining the Initial Shift: Some features of print culture.” The Book History Reader. David Finkelstein and Alistair McCleery. London and New York: Routledge, 2002. 151-173.

- Finkelstein, David and Alistair McCleery An Introduction to Book History. Routledge, 2005.

- Gunkel, David J. (2003). "What's the Matter with Books?". Configurations. 11 (3): 277–303. doi:10.1353/CON.2004.0026. S2CID 143294278.

- Johns, Adrian. “The Book of Nature and the Nature of the Book.” The Book History Reader. David Finkelstein and Alistair McCleery. London and New York: Routledge, 2002. 59-76.

- Katsh, Ethan. "Digital Lawyers: Orienting the Legal Profession to Cyberspace." University of Pittsburgh Law Review. v. 55, No. 4 (Summer 1994).

- -- III. The First Amendment, Print Culture, and the Electronic Environment

- Ong, Walter J. Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the Word. London and New York: Routledge, 1982. 78-116.

- Ong, Walter J. Ramus, Method and the Decay of Dialogue.

- Bolter, Jay David. Writing Space: The Computer, Hypertext, and the History of Writing. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1990.

- Bolter, Jay David, and Richard Grusin. Remediation: Understanding New Media. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1999.