War of the League of the Indies

The War of the League of the Indies (December 1570–1575) was a military conflict in which a pan-Asian alliance formed primarily by the Sultanate of Bijapur, the Sultanate of Ahmadnagar, the Kingdom of Calicut, and the Sultanate of Aceh, referred to by the Portuguese historian António Pinto Pereira as the "league of kings of India",[2] "the confederated kings", or simply "the league", attempted to decisively overturn Portuguese presence in the Indian Ocean through a combined assault on some of the main possessions of the Portuguese State of India: Malacca, Chaul, Chale fort, and the capital of the maritime empire in Asia, Goa.

| War of the League of the Indies | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

16th century Portuguese carracks (naus) and galleys | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

Co-belligerents: | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

Kingdom of Garsopa

| |||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Many Dead And wounded Plus With victims involved | Over 25,000 | ||||||

In what was one of the most critical moments of Portuguese presence in Asia, the Portuguese successfully resisted all sieges against the "league", with the exception of a small fort in the outskirts of Calicut that fell to the Zamorin, the ruler of Calicut. It would be the first time the Portuguese formally capitulated in India.[3]

Although the concept is anachronistic, it was a total war, as the Portuguese were forced to mobilize every available means to resist the assault.[4]

Background

In 1565, the Deccan sultanates joined forces to strike a decisive blow against the Vijayanagara Empire at the Battle of Talikota. The Hindu Vijayanagara Empire had been engaged in an incessant, irregular war against each of the Muslim sultanates of the Deccan Plateau individually, well before the Portuguese arrived in the Indian Ocean. The rulers of Vijayanagara, (whom the Portuguese referred to as simply the Rei Grande—"Great King") and especially Rama Raya, were powerful partners of the Portuguese, but with the Empire now thrown into chaos and plundered, the Adil Shah of Bijapur once more sought to recover the city of Goa, which had been lost over half a century ago to the Portuguese, and altogether expel them from the western coast of India.

Realizing that Portuguese naval power was key to their resilience, allowing each of their strongholds to reinforce each other by sea, the Adil Shah attempted to deny this advantage by convincing as many rulers to attack the Portuguese simultaneously, particularly the Sultan of Ahmadnagar, and the Zamorin of Calicut, who commanded considerable naval forces.[5] Religious animosity between the Portuguese and several Muslim dynasties of Asia would provide an easy point of accord towards this endeavour. Thus, envoys were dispatched to the Sultanate of Aceh in Sumatra, the Ottoman Empire, the Kingdom of Sitawaka in Ceylon, the Sultanate of Gujarat, and the Sultanate of Johor among others urging them to join the alliance and defeat the Portuguese once and for all.

The Sultanate of Gujarat

The Sultanate of Gujarat in northwestern India had long been one of the staunchest opponents of the Portuguese in India. Ever since the drowning of Sultan Bahadur during negotiations with the Portuguese in 1537 however, Gujarat had fallen to infighting. Thus the Sultanate of Gujarat was unavailable to move an attack against any of the immediate Portuguese strongholds, such as Diu, Bassein, and Daman. Such instability would open the way for the eventual conquest of Gujarat by the Mughals, in 1573.

The Ottoman Empire

The Sunni Sultan of Ahmadnagar had dispatched ambassadors to the Ottoman Empire with rich presents and a large tribute to gain the cooperation of the Ottoman navy, in wresting the control of the seas from the Portuguese, as early as 1564.[6] The Ottomans had access to the Red Sea following the annexation of Egypt in 1517, and Sultan Selim II agreed to join the effort. In about 1571, 25 galleys and 3 galleons set out from Suez, but they were held back by revolts in Jeddah and Yemen. These and the forthcoming Ottoman campaigns in the eastern Mediterranean, such as the Fourth Ottoman-Venetian War (which would culminate in the Battle of Lepanto), ensured that the Ottoman Empire would not participate in the conflict.[7]

Portuguese preparations

Reports and rumours of the preparations of the Adil Shah and the Nizam began reaching Goa through Portuguese merchants and allies by 1569. Although skeptical at first, believing the distrust between Indian rulers to be insurmountable for such a plan to be possible, the Portuguese Viceroy, Dom Luís de Ataíde eventually decided to dispatch a fleet of five galleons, one galley, and seven half-galleys with 800 men commanded by Dom Luís de Melo da Silva on August 24, 1570, to Malacca, to reinforce the city against a possible attack from the Sultanate of Aceh. Another fleet of three galleys and seventeen half-galleys with 500 men, under the command of Dom Diogo de Meneses was sent to patrol the Malabar coast and keep the vital trade routes with southern India, where the Portuguese city of Cochin was located, open and free of raiding from pirates.[8]

Dom Luís de Ataíde, a veteran from wars in India and the campaign of Emperor Charles V against the Lutherans in Europe, then gathered a council with some of the most important figures in Goa, including noblemen, clergymen, and members of the town hall of Goa.[9] The council advised him to abandon Chaul and concentrate his forces around Goa. Nevertheless, in October he decided to dispatch a further fleet of four galleys with 600 men commanded by Dom Francisco de Mascarenhas to defend that city.[10]

Defence of Goa

Conquered by Afonso de Albuquerque in 1510, Goa stood on an island surrounded by crocodile infested rivers that could, however, be waded across in some areas during the dry season. The closest and most important fording point to the city of Goa was the Passo Seco ("Dry Pass"), defended by the fortress of Benastarim.

As no more than 650 soldiers were left to defend Goa, every able-bodied man from among the casados (married settlers and Indo-Portuguese descendants) and 1500 Christian lascarins were mobilized. 1000 slaves were armed and divided into four squadrons; even further, 300 clergymen and 200 retired soldiers volunteered to participate in the defence of the city.[11]

Dom Luís de Ataíde decided to distribute his forces in 19 critical points along the eastern river banks, where artillery batteries were established, garrisoned with 20 to 80 men and a contingent of lascarins, to keep the colossal army of Bijapur from crossing. Every battery was to have visual contact with the next and their garrisons were not to leave their posts unless ordered to.[12] The deeper waters of the Mandovi and Zuari rivers, to the north and south respectively, were patrolled by four galleys, a half-galley, and twenty small galleys called foists. On the opposite shore northwest of Goa, the Portuguese fortress of Reis Magos was supported by an anchored galleon.

As the Viceroy had information that the Turks might join the "league", he armed a further 125 crafts of many different sizes to secure the control of the waters around Goa, although by then there weren't enough men to crew all the ships and defend the city simultaneously.[13]

The Siege of Goa

By December 28, 1570, general Nuri Khan arrived with the vanguard of the army from Bijapur, the Adil Shah[14] himself arriving eight days later with the bulk of his forces. According to the Portuguese it numbered 100,000 men strong, of which 30,000 were foot, 3,000 arquebusiers, and 35,000 horse, including 2,000 elephants, while the remaining were forced labourers. Besides over 350 bombards of which 30 were of colossal size, the army was also accompanied by several thousand dancing women.[15] He established a camp around his red tent to the east of the island of Goa, the infantry distributed ahead of Benastarim and the artillery placed into position to counter-fire the Portuguese batteries. The artillery of Bijapur began battering the fort, which was constantly repaired during the night. Throughout the Portuguese lines by the river banks, the Viceroy ordered torches and bonfires be lit on isolated positions by night, to give the impression of readiness and encourage the enemy to waste ammunition firing on them.[16]

Unable to ferry his troops across since the Portuguese controlled the river waters, the Adil Shah ordered that the Passo Seco along with the part of the river closest to the city be filled up with dirt to allow the army to cross over, forcing the labourers to dig under Portuguese fire:

[the Adil Shah] determined to cross over a causeway that he ordered be made (to the Island of João Lopes, from where the entry [into Goa] would be very easy) by the great amount of labourers that he had. And for all that were killed there, never would he give up the digging, for the Moors care so little for these people that they barely have them as a loss and for as many that they lost there, never are they short of more.[17]

By February 1571, the attack had ground down to a standstill, as the army of Bijapur was unable to overcome Portuguese defenses. Portuguese naval forces on the other hand, set to work devastating the shores and riversides of Bijapur, intercepting tradeships with provisions and capturing large quantities of livestock that was brought back to Goa.[18] Because of its large population, foodstuffs had to be rationed to feed the troops, but the city suffered no starvation, as the Portuguese kept the naval supply routes open.[18]

In early March, Dom Luís de Melo returned from Malacca, having successfully defended that city from an Acehnese attack, and brought reinforcements from Cochin, totalizing 1500 men.[19] On the 13th, the Adil Shah ordered a decisive assault across the river, under the command of a Turk, Suleimão Agá. 9,000 men waded across the river either by foot or on small crafts and many reached the opposite banks, but came under heavy fire from Portuguese ships, artillery batteries, and arquebuses, until they were finally shattered by a Portuguese counter-attack of 300 men under the command of Luís de Melo and Dom Fernando de Monroy, who landed on the opposite shore, killing about 3,000 enemies. By the late afternoon, a strong storm spelled the end of the assault.

The Viceroy also managed to sow dissent in the enemy's ranks: by April many had grown tired of the conflict, and Dom Luís de Ataíde plotted with general Nuri Khan, who had openly opposed the conflict from the beginning, to rebel or even assassinate the Adil Shah, which brought the Sultan wide-range suspicion towards his own command. According to the 16th century Indian historian Zinadim, this the main reason behind the failure of the siege:

Besides that, some of his [Adil Shah's] ministers colluded with the franks to arrest him, and place on the throne a close kin, who was in Goa amongst the franks; informed as he was of this plot, Adil Shah was afraid and fled the troops; and when he was in safe place he had the plotters arrested and threw them in prison, inflicting on them great sentences and relieving them of his benefaction. In these circumstances Adil Shah was forced to make peace.[20]

As the weather worsened with the coming of the monsoon rains, the Adil Shah kept his army camped in front of Goa, while torrential storms forced operations down to a minimum and the Portuguese conducted occasional raids under the rain. By August the 15th,[21] with his army profoundly demoralised, afflicted by the monsoon weather and suffering from shortage of supplies, the Adil Shah ordered the steady withdrawal of his forces, having lost over 8,000 men, 4,000 horses, 300 elephants, and over 6,000 oxen in the campaign.[22] He abandoned 150 pieces of artillery in the river.[23] By December 13, 1571, the Shah formally requested peace with the Portuguese.

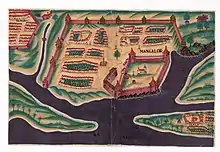

Siege of Mangalore, April 1571

As the Vijayanagara Empire collapsed, the Portuguese took possession of the port city of Mangalore in 1568, where they constructed a small fort to prevent the city from falling to Muslim control. In 1571 however, the nearby Queen of Ullal contracted a Malabarese privateer, whom the Portuguese identified as Catiproca Marcá (Kutti Pokkar Marakkar), to capture the fort that was by then defended solely by 15 Portuguese soldiers, plus the casados and about a hundred Christian lascarins. Catiproca had 8 half-galleys, and in April 1571 his forces attempted to scale the fort's walls in the middle of the night. He was detected, and the small garrison managed to repel the attack.[24] Having failed the attack, Catiproca reembarked his forces but two days later he encountered the fleet of Dom Diogo de Meneses, who had been sent to the Malabar coast specifically to ensure the safety of allied shipping from pirates, and his fleet destroyed.[25]

Siege of Honavar July 1571

In 1569, the Viceroy Dom Luís de Ataíde oversaw the takeover of the coastal town of Honavar, where a small fort was built. In the middle of July 1571, during the monsoon, it was attacked by 5000 men and 400 horse of the neighbouring Queen of Garsopa, instigated by the Adil Shah of Bijapur, who provided 2,000 of those men.[26] The Viceroy dispatched 200 men to reinforce the fort by sea aboard a galley and eight foists. The small fleet managed to reach the fort despite the monsoon weather and immediately conducted a successful attack on the enemy army and the fort held on.[27]

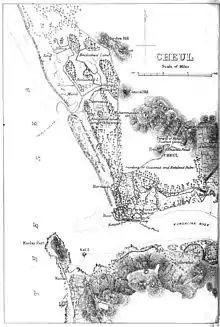

The Siege of Chaul

Although protected by a small fort built near the shoreline in 1521, the city of Chaul was not fortified. Just as the threat of a siege became evident, the captain of the city, Dom Luís Freire de Andrade ordered the evacuation of women, children, and elderly to Goa and barricades be set up in the main streets with artillery. In October, Dom Francisco de Mascarenhas arrived from Goa with 600 men and immediately ordered the digging of an extensive network of ditches, trenches, earthen walls, and defensive works around the outer perimeter of the city, fortifying outer houses and monasteries into blockhouses and demolishing others to clear the line of fire for the artillery.[28]

The warships were distributed in the river to the east, so as to deny the enemy a venue of approach to the city along the river banks with their artillery.[29] This way, it would only be possible to approach the city through a swampy, narrow section to the north, forcing the enemy to bottleneck their forces.[30]

On December 15, the vanguard of the army of Ahmadnagar, arrived under the command of an Ethiopian general, Faratecão (formerly at the service of the Sultan of Gujarat), and clashed with the Portuguese, who repelled the attack.[31] The Nizam arrived with the rest of his army on December 21.[31] Through a spy, the Portuguese determined that the forces of the Nizam Ul-Mulk Shah of Ahmadnagar (Nizamaluco in Portuguese) might have risen up to 120,000 men, including many Turkic, Abyssian, Persian, Afghan, and Mughal mercenaries, 38,000 horsemen, and 370 war elephants, supported by 38 heavy bombards. Not all were fighting men; according to António Pinto Pereira:

The infantry passed one-hundred and twenty thousand, but they do not rest on them their strength, nor do they care but of the cavalry and artillery for matters of war; the footmen are brought along for the march and for service in the camp and as labourers, rather than any confidence they might have of them. In said camp came 12,000 konkanis, very good people in war, mustered by the tanadares of Konkan, which lays between the edge of the Ghats and the sea, as bomb throwers, bowmen and a few arquebusiers and 4,000 field craftsmen, blacksmiths, stonemasons and carpenters.[32]

The Portuguese for their part numbered 900 soldiers, but each fully equipped with plate armour and matchlocks, compared to only 300 arquebusiers on the enemy side.[33] But because cavalry and elephants were rendered useless in a siege by the marshlands and trenches, the infantry would have to bear the brunt of the assault.[30]

The Nizam assembled the rest of his forces around the north and northeast of the city. On the 21st day of December he breached the fortified perimeter around the monastery of São Francisco on the outskirts of Chaul, but the heavy fire of the Portuguese arquebuses and a swift counter-attack forced them to retreat. In the meantime, the Nizam set his powerful artillery to the east of the city under the supervision of a Turkish general, Rumi Khan, near a village the Portuguese dubbed Chaul de Cima (Upper Chaul).

At the same time, about 2,000 horsemen of the Nizam proceeded to devastate the lands owned by Portuguese around Bassein and Daman, but were repelled trying to assault a small Portuguese fort at Caranjá near Bombay, defended by 40 Portuguese soldiers.

On January 10, the batteries of the Nizam began bombarding the outer blockhouses of Chaul, reducing them to rubble after a few days. One such piece earned from the Portuguese the nickname "Orlando Furioso".[34]

In February, a small fleet of 5 half-galleys and 25 smaller craft with 2,000 men from Calicut, commanded by Catiproca Marcá, arrived in Chaul to meet up with the forces of the Nizam, under cover from the night. The Portuguese had five galleys and eleven foists in the harbour, but the Malabarese avoided clashing with the Portuguese galleys.[35]

Fighting around Chaul broke down to trench warfare, as the army of Ahmadnagar dug trenches towards Portuguese lines to cover from their gunfire, amidst frequent Portuguese raids. The Portuguese dug counter-mines to neutralize them.

At this point, a Portuguese captain Agostinho Nunes introduced for the first time an innovation that the Portuguese historian António Pinto Pereira considered to have been critical in withstanding the enemy bombardment: he ordered his soldiers to dig a special trench with a firing parapet, protected by sloped earth—a "fire trench".[30]

In late February the Nizam ordered a general assault on the city, but was repelled with heavy losses, just as the Portuguese received important reinforcements by sea from Goa and Bassein. Fighting continued over the possession of the outer strongholds throughout the months of March and April, as the army of the Nizam suffered heavy casualties. Following a sortie of the Portuguese on April 11, the Nizam ordered the city to be subjected to a general bombardment, which demolished several strongholds and sunk the Viceroy's galley anchored in the harbour.[36]

Yet the disparity in numbers was still immense, and despite frequent sorties, little by little, the Portuguese were forced to give ground to the great mass of enemies, retreating from several defensive lines until by May they were finally cornered in their last line of defence.[37] For the following thirty days, the Portuguese desperately defended their lines against several waves of attackers, discharging volleys of matchlock fire and hurling gunpowder grenades at day and night. Portuguese casualties now amounted to over 400, besides their Hindu auxiliaries and civilians.[37]

The forces of the Nizam however, failed to overcome the Portuguese in time—they had successfully held out through the monsoon season, and now that it had passed the weather finally allowed vessels to flow freely into the city, bearing fresh reinforcements nearly every day; when on June 29 the Nizam ordered a general assault on the city, the Portuguese repelled the attack and pushed his army back to their camp in a complete rout, capturing cannon, weapons, and destroying the saps and siegeworks along the way, having slain over 3,000 of the besiegers at the end of six hours fighting. After this setback, on July 24 Murtaza Nizam Shah requested peace, and withdrew his army.[37]

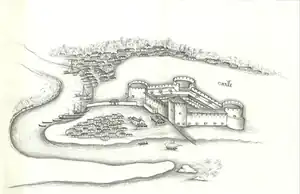

The Siege of Chale, July–November 1571

The Sultans of Bijapur and Ahmednagar considered the naval forces of Calicut vital in contesting the sea lanes from the Portuguese.[5] The Zamorin nevertheless waited until the monsoon started to besiege the Portuguese fortress by the coastal town of Chale (Chaliyam), hoping that the weather would prevent the Portuguese from shipping over reinforcements. Although formally at peace, in July the Zamorin initiated the attack, bombarding the fortress with 40 cannon. Despite the weather, the Portuguese managed to send reinforcements and a few supplies through to the fortress as soon as news of the attack reached Goa. The Zamorin placed an artillery battery on the mouth of the river that effectively blockaded Portuguese shallow draft vessels from passing through. The captain of the fortress, 80-year-old Dom Jorge de Castro, influenced by the King of Tanur a local ally of the Portuguese, decided to surrender the fortress on November 4, 1571, in what became the first formal capitulation of territory by the Portuguese, ever since arriving in India. The Zamorin immediately demolished the fort and sent Dom Jorge back to Goa.[39]

At Goa, Dom Jorge was arrested,court-martialed and executed. The court concluded that he had had the means to resist a prolonged siege.

With the withdrawal of the forces of Adil Khan from Goa, the Portuguese then passed on the offensive against the Zamorin, blockading Calicut and devastating the kingdom, until he was also forced to sue for peace.[3]

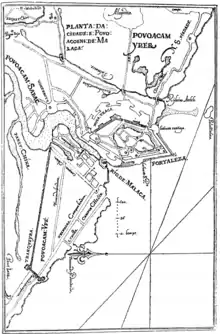

Sieges of Malacca

The reinforcements sent from Goa in August 1570, under the command of Dom Luís de Melo da Silva, proved critical in preventing Malacca from being besieged at the same time as Goa and Chaul: in November 1570, the Portuguese destroyed an Aceh fleet of 100 ships by the mouth of River Formoso to the south of Malacca, killing the prince-heir of Aceh, and thus forcing the Sultan to postpone the attack to a later date. Dom Luís de Melo then returned to India with his forces the following January, to assist in the defence of Goa.[40]

Siege of Malacca October–November 1573

Nevertheless, by October 1573 Malacca was scarcely defended as most soldiers were embarked in commercial missions, and the Sultan of Aceh had gathered 7,000 men and a fleet of 25 galleys, 34 half-galleys, and 30 craft and requested assistance from the Queen of Kalinyamat (Japará in Portuguese) to besiege it.[41]

Aceh had material support from the Qutb Ul-Mulk Shah of Golkonda (Cotamaluco in Portuguese) who, lacking a Portuguese settlement or fortress to attack by his borders, limited himself to providing cannon and supplies to the Acehnese.[42]

On October 13, without waiting for its ally, the Aceh force landed south of Malacca and dealt severe casualties to the Portuguese who attempted a sortie. Thereafter they began attacking the fortress with incendiary projectiles, causing several fires but a sudden storm put out the fires and scattered the fleet, and the assault was called off. The Aceh commander then decided to establish a naval base by the Muar River and force the city to surrender through a naval blockade instead, capturing any passing tradeships that carried supplies to the city. An attempt to board a galleon and two carracks anchored by the Island of Naus (modern-day Pulau Melaka) was met with heavy resistance and suffered severe casualties from Portuguese gunfire.[41]

On November 2, a carrack commanded by Tristão Vaz da Veiga arrived with the newly appointed captain of Malacca, Dom Francisco Rodrigues, along with important reinforcements. The captain immediately summoned a council to assess the situation. The Aceh fleet was causing severe shortages in Malacca, and it was decided that it was urgent to organize a force to repel it as soon as possible. Thus, a carrack, a galleon, and eight half-galleys were munitioned and set out on November 16 to the mouth of the River Formoso, where the enemy fleet had shifted to. With the river in sight, the Aceh fleet set out while the wind was in their favour to meet the Portuguese. Despite being outnumbered the Portuguese oar ships positioned themselves ahead of the carrack and the galleon to board the Acehnese galleys in the vanguard. The crews of the oar ships fired volleys of shrapnel and matchlock fire and threw gunpowder grenades, while the carrack and the galleon fired their heavy caliber artillery, sinking many Acehnese oar ships. Despite having Turkish gunners and cannon, the Acehnese artillery was not overly effective.[43] Once their flagship, a very large galley with over 200 fighting men, was boarded and its flag taken down by the Portuguese, the remainder of the Aceh fleet scattered, having lost four galleys and five half-galleys, with several more sunk or beached due to the bad weather. The Portuguese suffered ten dead.[43]

Siege of Malacca, October–December 1574

Despite the Aceh defeat, the Queen of Kalinyamat organized an armada with which to attack Malacca, composed of over 70 to 80 junks and over 200 craft carrying 15,000 men under the command of Kyai Demang—transliterated as Queahidamão, Quilidamão or Quaidamand by the Portuguese[44][45]—although with very little artillery and firearms.[46] Malacca was defended by about 300 Portuguese.[47]

By October 5, 1574, the armada anchored within the nearby River of Malaios and began landing troops, but the besiegers suffered Portuguese raids that caused great damage to the army when assembling stockades around the city.[46]

As the captain of Malacca (on account of the sudden death of his predecessor), Tristão Vaz da Veiga decided to arm a small fleet of a galley and four half-galleys and about 100 soldiers and head out to the River of Malaios, in the middle of the night. Once there, the Portuguese fleet entered the river undetected by the Javanese crews, and resorting to hand-thrown fire bombs set fire to about thirty junks and other crafts, catching the enemy fleet entirely by surprise, and capturing ample supplies amidst the panicking Javanese. Kyai Demang afterwards decided to fortify the river mouth, constructing stockades across the river, armed with a few small cannon, but it too was twice destroyed by the Portuguese. Afterwards, Tristão Vaz da Veiga ordered Fernão Peres de Andrade to blockade the river mouth with a small carrack and a few oarships, trapping the enemy army within it and forcing the Javanese commander to come to terms with the Portuguese. Not coming to any agreement, in December Tristão Vaz finally ordered his forces to withdraw from the river mouth. The Javanese hastily embarked in the few ships they had left, overloading them, and sailed out of the river, only to be then preyed upon by Portuguese ships, who chased them down with their artillery. The Javanese lost almost all of their junks and suffered about 7,000 dead at the end of the three-month campaign.[48]

Final siege of Malacca, February 1575

Although every attempt to conquer Malacca's had so far failed, the Acehnese still maintained hopes that the Portuguese might be caught debilitated after fighting two consecutive sieges. Indeed, the previous attacks had left the Portuguese garrison decimated, crops destroyed, and foodstuffs and gunpowder in the city nearly exhausted.

Thus in the final day of January 1575, a new Acehnese armada composed of 113 vessels, which included 40 galleys, once more laid siege to Malacca.[49] The captain of Malacca Tristão Vaz da Veiga had gotten reports of the imminent threat, and so had dispatched the merchants away from Malacca on their vessels (to prevent their collusion with the Acehnese[50]), merchant ships to fetch supplies in Bengal and Pegu, and urgent messages to the Viceroy in Goa requesting reinforcements, knowing full well these would not be forthcoming at least until May because of the monsoon season, if they came at all.[51]

To keep the naval supply lines of the city open, he stationed 120 Portuguese soldiers on a galley, a caravel, and a carrack.[52] Yet the disparity between forces was now too great, and the small flotilla was overwhelmed by the entire Acehnese fleet.[53]

Within Malacca there were now only 150 Portuguese soldiers to defend it [54] plus the corps of native soldiers; Tristão Vaz realized to hole them up in the walls could be disadvantageous, as it might hint the enemy of their dwindling numbers. In spite of this, he had his last remaining men perform short sorties to fool the Acehnese of their numbers.[55]

Ultimately, the third siege of Malacca was brief: only seventeen days after landing, the Acehnese lifted the siege and sailed back to Sumatra.[56] The Portuguese claimed the Acehnese commander hesitated in ordering a general assault, though it's just as possible the Acehnese retreated due to internal problems.[57] In June, Dom Miguel de Castro arrived from Goa with a fleet of a galleass, three galleys, and eight half-galleys to relieve Tristão Vaz as captain of Malacca, along with 500 soldiers in reinforcements.[57]

Aftermath

By the passion of Our Lord, fear not for your fortresses built in our fashion in these parts, with moats, towers and artillery, well supplied and garrisoned, though you might be told there that they are under siege; if there is no betrayal, God willing, there is no reason to fear that the moors may contest your fortresses and anything you ought to lay hands upon; it should come as no surprise that kings and lords would besiege those you take from them, once and twice and ten times; but they won't take any fortress from the Portuguese wearing their helmets among the battlements.[58]

— Letter of Afonso de Albuquerque to King Manuel I, 1512

Besides proving the difficulty of coordinating an attack on such scale, the combined assault of some of the most powerful kingdoms in Asia on Portuguese possessions failed to achieve any significant objectives, let alone decisively overturn Portuguese influence in the Indian Ocean. On the contrary, the rulers of Bijapur, Ahmadnagar, and the Zamorin were forced to come to terms that were favourable to the Portuguese: among other terms, they would charge no fees from Christian merchants, harbour no enemy fleets of the Portuguese, and resume paying tribute to Goa, in exchange for Portuguese assistance in clearing the western Indian coast of piracy and authorization to trade in Portuguese ports (provided every ship carried an appropriate trading license, or cartaz), essentially recognizing Portuguese dominion of the sea.[59][60]

The fort of Chale had little strategic interest, and its loss did not represent a serious setback for the Portuguese.[61] The fall of Vijayanagara however, had indirectly greater strategic implications for the Portuguese State of India, whose finances suffered a severe blow with the loss of the extremely lucrative horse trade with the Empire.[62] It would take the assistance of other European powers to challenge the hegemony of the Portuguese, who would suffer their first serious setback with the fall of Hormuz, at the hands of combined Anglo-Persian force, about forty years later in 1622.

Dom Luís de Ataíde was succeeded in office by Dom António de Noronha in September 1571. On his arrival in Portugal in July 1572, Ataíde was solemnly received by King Sebastian, and awarded several honours including the command of the planned expedition to Morocco—which he turned down, for disagreeing with the nature of the undertaking. In 1578, he was reappointed Viceroy of India, and would in fact be the last Viceroy nominated by the Portuguese Crown before the Iberian Union. He died in office in 1581.

Situation in the Moluccas, 1570–1575

In the Moluccas, the great distances made it extremely difficult, if not completely impossible, for the Portuguese Crown to direct a consistent policy in such a remote region, meaning it was often reduced to the initiative of individual captains assigned to the archipelago.

In late 1570, the captain of Ternate Diogo Lopes de Mesquita had Sultan Khairun of Ternate assassinated, as the latter had been persecuting native Christians for some time. This proved untimely, as it provoked a major rebellion led by the late Sultan's son Baabullah (Babu in Portuguese), who allied with the Sultan of Tidore with support of the Javanese against the Portuguese.[63] Although seemingly unrelated with the "league", the larger conflict in mainland Asia left the Portuguese incapable of sending sufficient reinforcements to the Moluccas in each sailing season, between the monsoons. In a prolonged conflict that extended to Portuguese positions in Gilolo, Ambon, and Banda, the critically isolated Portuguese could count on little aid to defend not just themselves, but also the nascent communities of local Christians.

Eventually, in 1575, with dwindling supplies and no hope of reinforcement, the less than 100 remaining defenders of the fortress of Ternate surrendered, at the end of a five-year long siege, to Sultan Babu. The Sultan then occupied the fort as his royal palace. Probably fearing retaliation from the Portuguese, he nonetheless allowed a few (about 18 married men) to remain on the island to maintain trade which, given the circumstances, the next Portuguese captain, Lionel de Brito, accepted upon arriving, just three days after the surrender, and was allowed to trade as usual.[64]

In March 1576, the Portuguese began construction of a new fortress on Ambon, that henceforth became the center of Portuguese activity in the Moluccas. In 1578, as per request of its Sultan, the Portuguese built a new fort on Tidore, to where those still in Ternate relocated.

In popular literature

- In Conquerors: How Portugal Forged the First Global Empire (2015), Roger Crowley references the conflict very briefly.[65]

References

- Pereira, António Pinto (1617). História da Índia, ao Tempo Que a Governou o Vice-Rei D. Luiz de Ataíde (1986 reprint ed.). Lisbon: Imprensa Nacional Casa da Moeda.

- Couto, Diogo do (1673). Da Ásia, Década Oitava (1786 ed.). Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal. ISBN 9789722705325.

- Couto, Diogo do (1673). Da Ásia, Década Nona (1786 ed.). Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal.

- Lemos, Jorge de (1585). História dos Cercos de Malaca. Lisbon: Biblioteca Nacional.

- Monteiro, Saturnino (2011). Portuguese Sea Battles, Volume III - From Brazil to Japan, 1539-1579. ISBN 9789899683631.

- Feio, Gonçalo (2013). O ensino e a aprendizagem militares em Portugal e no Império, de D. João III a D. Sebastião: a arte portuguesa da guerra (PDF) (Thesis). University of Lisbon.

- M. Zinadim Ben-Ali Ben-Ahmed (1898) [1583]. História dos Portugueses no Malabar. Translated by Lopes, David (2010 Portuguese ed.). Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 9781167636523.

- Goertz, R.O.W (1985). "Attack and Defense Techniques in the Siege of Chaul 1570-1571". In Luís de Albuquerque; Inácio Guerreiro (eds.). Actas do II Seminário Internacional de História Indo-Portuguesa. Lisbon: Instituto de Investigação Científica Tropical, Centro de Estudos de História e Cartografia Antiga.

Notes

- Monteiro 2011, p. 328.

- Liga dos Reis da Índia, in Pereira 1617, 1986 edition, pg 143

- Monteiro 2011, p. 362.

- Feio 2013, p. 135.

- Pereira 1617, p. 146.

- Nuno Vila-Santa, in Temas e Factos: Talikota, Batalha de. Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Humanas, Nova University of Lisbon.

- Monteiro 2011, pp. 334–340.

- Monteiro 2011, pp. 354–355.

- Pereira 1617, p. 324.

- Pereira 1617, p. 328.

- Pereira 1617, p. 349.

- Pereira 1617, p. 348.

- Pereira 1617, pp. 339–340.

- Hidalcão or Hidalxá in Portuguese sources

- Pereira 1617, p. 356.

- Cruz, Maria Augusta Lima (1992). Diogo do Couto e a década 8a da Asia (in Brazilian Portuguese). Comissão Nacional para as Comemorações dos Descobrimentos Portugueses. ISBN 978-972-27-0532-5.

- In Portuguese: [...]Determinara ordenar-lhe a passagem per terra, mãdando trabalhar (em hum entulho que determinara fazer no rio até a ilha de Ioam Lopes, donde a entrada lhe ficaria muito fácil) grãdissima soma de gastadores & officiais. E por muitos que se lhe matavã, nunca desitia do entulho: porque desta sorte de gente fazem os mouros tã pouca estima que quasi a não ham por perda, & por muita que percão della nunca lhe falece in Pereira, 1616, pg 411.

- Pereira 1617, p. 572.

- Pereira 1617, p. 466.

- Além disso alguns dos seus ministros estavam conluiados com os frangues para o prenderem, e porem no trono um parente próximo, que estava em Goa com os frangues; Adilxá informado desta trama teve medo e fugiu das tropas; e quando esteve em lugar seguro mandou prender os conspiradores e meteu-os na prisão, inflingindo-lhes grandes penas e retirando-lhes as suas mercês. Nestas circunstâncias foi forçoso a Adilxá fazer a paz. in ZINADIM, História dos Portugueses no Malabar, Portuguese translation by David Lopes, 1898, 2010 edition, Kessinger Publishing.

- Pereira 1617, p. 624.

- Pereira 1617, p. 625.

- Pereira 1617, p. 623.

- Pereira 1617, p. 461.

- Pereira 1617, p. 464.

- Pereira 1617, p. 573.

- Pereira 1617, p. 574.

- Pereira 1617, p. 361-353.

- Goertz 1985, p. 274.

- Goertz 1985, p. 282.

- Pereira 1617, p. 368.

- In Portuguese: A gente de pé passava de cento & vinte mil, mas nesta não fundam elles o poder, nem fazem caso pera os effeitos de Guerra, senão da cavaleria, & artelharia: e porque a peonagem mais a trazem pera os abalos & serviço do arrayal & em lugar de gastadores, que por outra confiança que tenham della. Com quanto em este campo vinham doze mil piões Conquanis muito boa gente de Guerra, que os Tenadares tiraram da terra do Concão, na fralda da terra do Gate até ao mar, que sam bombeiros, frecheiros & alguns espingardeiros & quarto mil officiaes de campo, ferreiros, pedreiros, & carpinteiros in Pereira, 1617, pg.380

- Goertz 1985.

- Pereira 1617, p. 381.

- Monteiro 2011, pp. 344–346.

- (a cannonball from the largest cannon of the Nizam bounced off a fortified blockhouse, demolishing it, and then hit the galley).

- Goertz 1985, p. 280.

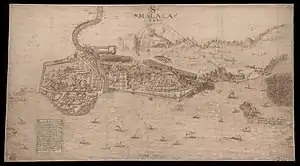

- 16th century depiction, by Gaspar Correia. Erected in 1531, about 10km from Calicut. By 1570, part of the garrison lived among the populace, as casados.

- Monteiro 2011, pp. 361–362.

- Monteiro 2011, pp. 327–330.

- Monteiro 2011, p. 386.

- Lemos 1585, p. 38.

- Monteiro 2011, p. 390.

- Hayati, Chusnul (2010). Ratu Kalinyamat: Ratu Jepara Yang Pemberani. Citra Leka dan Sabda. Page 23.

- Koek, E. (1886), "Portuguese History of Malacca", Journal of the Straits Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 17: 117–149. Page 145.

- Monteiro 2011, p. 394.

- Monteiro 2011, p. 396.

- Monteiro 2011, pp. 395–397.

- Lemos 1585, p. 118.

- Lemos 1585, p. 126.

- Lemos 1585, p. 119.

- Monteiro 2011, p. 406.

- Lemos 1585, p. 122.

- Lemos 1585, p. 47.

- Lemos 1585, p. 130.

- Lemos 1585, p. 131.

- Monteiro 2011, p. 408.

- In Portuguese: As vossas fortalezas feitas à nossa usança com cavas, torres e artilahria, bem providas e boa gente, com ajuda da paixão de Nosso Senhor não tenhais receio delas nestas partes, ainda que cos digam lá que estão cercadas; porque, mediante Deus, se aí não houver traição, não há aí que temer de os mouros contrariarem vossas fortalezas e cousas de que vos convém deitar mão; não é de estranhar cercarem-nas os reis e senhores a que as tomardes, se serem cercadas uma e duas e dez vezes; mas a portugueses cos capacetes nas cabeças entre as ameias não lhe tomam assim a fortaleza in António Baião (1957): Cartas para El-Rei D. Manuel I, Sá da Costa Editora, Lisbon, p.58

- Pereira 1617, p. 616-618.

- Diogo do Couto (1673), Da Ásia, Década Nona pp.17–19, 1786 edition, Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal

- Monteiro 2011, p. 339.

- Monteiro 2011, p. 371.

- Monteiro 2011, p. 337.

- Monteiro 2011, p. 414.

- Crowley, Roger (2015). Conquerors: How Portugal Forged the First Global Empire, pg. 362. "Even a massive pan-Indian assault on Goa and Chaul in the years of 1570-1 died at the walls. The Franks could not be dislodged"