Pjetër Bogdani

Pjetër Bogdani (Italian: Pietro Bogdano; 1627[4] – 6 December 1689) was the most original writer of early literature in Albania. He was author of the Cuneus Prophetarum (The Band of the Prophets), 1685, the first prose work of substance written originally in (Gheg) Albanian (i.e. not a translation). He organized a resistance against the Ottomans and a pro-Austrian movement in Kosovo in 1689 that included Muslim and Christian Albanians.[5]

Pjetër Bogdani | |

|---|---|

Pjetër Bogdani on a 1989 Albania stamp | |

| Born | circa 1627 |

| Died | 6 December 1689 (aged 58) |

| Nationality | Albanian |

| Other names | Pietro Bogdano |

| Occupation(s) | Catholic priest, writer, poet |

| Known for | author of the first prose work of substance originally written in Albanian |

Life and work

He was born in the village of Gur in the area of Has, near Prizren in 1627.[6] Its exact location is unknown,[7] but Robert Elsie has proposed two modern day villages of Gjonaj and Breg Drini in Prizren area.[8] Bogdani was educated in the traditions of the Catholic church.[9] His uncle Andrea Bogdani (c. 1600–1683) was Archbishop of Skopje and author of a Latin-Albanian grammar, now lost. Bogdani is said to have received his initial schooling from the Franciscans at Chiprovtsi in modern northwestern Bulgaria and then studied at the Illyrian College of Loreto near Ancona, as had his predecessors Pjetër Budi and Frang Bardhi. From 1651 to 1654 he served as a parish priest in Pult and from 1654 to 1656 studied at the College of the Propaganda Fide in Rome where he graduated as a doctor of philosophy and theology. In 1656, he was named Bishop of Shkodra, a post he held for twenty-one years, and was also appointed Administrator of the Archdiocese of Antivari (Bar) until 1671.

During the most troubled years of the Ottoman - Austrian war, 1664–1669, he took refuge in the villages of Barbullush and Rjoll near Shkodra. A cave near Rjoll, in which he took refuge, still bears his name. Eventually, he was captured by the Ottomans and imprisoned in the fort of Shkodër. The bishop of Durrës, Shtjëfen Gaspëri later reported to the Propaganda Fide that he was rescued by the brothers Pepë and Nikollë Kastori. In 1677, he succeeded his uncle as Archbishop of Skopje and Administrator of Roman Catholic parishes in the Kingdom of Serbia.[10] The Gashi and Krasniqja tribes were in frequent conflicts with one another until 1680, when Pjetër Bogdani managed to reconcile 24 blood feuds between the two tribes.[11] His religious zeal and patriotic fervour kept him at odds with Ottoman forces, and in the atmosphere of war and confusion which reigned, he was obliged to flee to Ragusa, from where he continued on to Venice and Padua, taking his manuscripts with him. In Padua he was cordially received by Cardinal Gregorio Barbarigo, Bishop of Padua at that time, whom he had served in Rome. Cardinal Barbarigo was responsible for the church affairs in the East and as such he had a keen interest in the cultures of the Levant, including Albania. The cardinal had also founded a printing press in Padua, the Tipografia del Seminario, which served the needs of oriental languages and had fonts for Hebrew, Arabic and Armenian. Barbarigo was thus well disposed, willing and able to assist Bogdani in the latter's historic undertaking.

After arranging for the publication of the Cuneus Prophetarum, Bogdani returned to the Balkans in March 1686 and spent the next years promoting resistance to the armies of the Ottoman Empire, in particular in Kosovo. He and his vicar Toma Raspasani played a leading role in the pro-Austrian movement in Kosovo during the Great Turkish War.[12] He contributed a force of 6,000 Albanian soldiers to the Austrian army which had arrived in Pristina and accompanied it to capture Prizren. There, however, he and much of his army were met by another equally formidable adversary, the plague. Bogdani returned to Pristina but succumbed to the disease there in 6 December 1689.[13] His nephew, Gjergj Bogdani, reported in 1698 that his uncle's remains were later exhumed by Turkish and Tatar soldiers and fed to the dogs in the middle of the square in Pristina. So ended one of the great figures of early Albanian culture, the writer often referred to as the father of Albanian prose.

Poetry

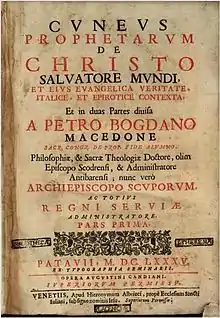

It was in Padua in 1685 that the Cuneus Prophetarum, his vast treatise on theology, was published in Albanian and Italian with the assistance of Cardinal Barbarigo. Bogdani had finished the Albanian version ten years earlier but was refused permission to publish it by the Propaganda Fide which ordered that the manuscript be translated first, no doubt to facilitate the work of the censor. The full title of the published version is:

"Cvnevs prophetarvm de Christo salvatore mvndi et eivs evangelica veritate, italice et epirotice contexta, et in duas partes diuisa a Petro Bogdano Macedone, Sacr. Congr. de Prop. Fide alvmno, Philosophiae & Sacrae Theologiae Doctore, olim Episcopo Scodrensi & Administratore Antibarensi, nunc vero Archiepiscopo Scvporvm ac totivs regni Serviae Administratore" (The Band of the Prophets Concerning Christ, Saviour of the World and his Gospel Truth, edited in Italian and Epirotic and divided into two parts by Pjetër Bogdani of Macedonia, student of the Holy Congregation of the Propaganda Fide, doctor of philosophy and holy theology, formerly Bishop of Shkodra and Administrator of Antivari and now Archbishop of Skopje and Administrator of all the Kingdom of Serbia.)

The Cuneus Prophetarum was printed in the Latin alphabet as used in Italian, with the addition of the same Cyrillic characters employed by Pjetër Budi and Frang Bardhi. Bogdani seems therefore to have had access to their works. During his studies at the College of the Propaganda Fide, he is known to have requested Albanian books from the college printer: "five copies of the Christian Doctrine and five Albanian dictionaries," most certainly the works of Budi and Bardhi. In a report to the Propaganda Fide in 1665, he also mentions a certain Euangelii in Albanese (Gospels in Albanian) of which he had heard, a possible reference to Buzuku's missal of 1555.

The Cuneus Prophetarum was published in two parallel columns, one in Albanian and one in Italian, and is divided into two volumes, each with four sections (scala). The first volume, which is preceded by dedications and eulogies in Latin, Albanian, Serbian and Italian, and includes two eight-line poems in Albanian, one by his cousin Luca Bogdani and one by Luca Summa, deals primarily with themes from the Old Testament: i) How God created man, ii) The prophets and their metaphors concerning the coming of the Messiah, iii) The lives of the prophets and their prophecies, iv) The songs of the ten Sibyls. The second volume, entitled De vita Jesu Christi salvatoris mundi (On the life of Jesus Christ, saviour of the world), is devoted mostly to the New Testament: i) The life of Jesus Christ, ii) The miracles of Jesus Christ, iii) The suffering and death of Jesus Christ, iv) The resurrection and second coming of Christ. This section includes a translation from the Book of Daniel, 9. 24–26, in eight languages: Latin, Greek, Armenian, Syriac, Hebrew, Arabic, Italian and Albanian, and is followed by a chapter on the life of the Antichrist, by indices in Italian and Albanian and by a three-page appendix on the Antichità della Casa Bogdana (Antiquity of the House of the Bogdanis).

The work was reprinted twice under the title L'infallibile verità della cattolica fede, Venice 1691 and 1702 (The infallible truth of the Catholic faith).

The Cuneus Prophetarum is considered to be the masterpiece of early Albanian literature and is the first work in Albanian of full artistic and literary quality. In scope, it covers philosophy, theology and science (with digressions on geography, astronomy, physics and history). With its poetry and literary prose, it touches on questions of aesthetic and literary theory. It is a humanist work of the Baroque Age steeped in the philosophical traditions of Plato, Aristotle, St Augustine, and St Thomas Aquinas. Bogdani's fundamental philosophical aim is a knowledge of God, an unravelling of the problem of existence, for which he strives with reason and intellect.

Bogdani's talents are certainly most evident in his prose. In his work we encounter for the first time what may be considered an Albanian literary language. As such, he may justly bear the title of father of Albanian prose. His modest religious poetry is, nonetheless, not devoid of interest. The corpus of his verse are the Songs of the Ten Sibyls (the Cumaean, Libyan, Delphic, Persian, Erythraean, Samian, Cumanian, Hellespontic, Phrygian, and Tiburtine), which are imbued with the Baroque penchant for religious themes and Biblical allusions.[14]

Legacy

Pjetër Bogdani is depicted on the obverse of the Albanian 1000 lekë banknote issued since 1996.[15]

References

- Historical Dictionary of Albania, Robert Elsie, Rowman & Littlefield, 2010, p. 54., ISBN 0810861887

- The parishes of Gur, Shegjec, Zym, and Zogaj in Has near Prizren were strictly Catholic and Albanian. Studies on Kosova, Arshi Pipa, Sami Repishti, East European Monographs, 1984, ISBN 0880330473, p. 30.

- Kosovo: A Short History, Author Noel Malcolm, Publisher Macmillan, 1998, p. 125., ISBN 0333666127

- Bardhyl Demiraj (2016). Grimca biografike mbi autorët tanë të vjetër (III): Rinia dhe formimi teologjik-intelktual i Pjetër Bogdanit, in: "Hylli i Dritës" 2, p. 21-23, Shkodër. “Pietro Bugdano Albanese entrò in Collegio a di 13 di 1642 è di età d’anni 15 in circa.”

- Rebels, Believers, Survivors - Noel Malcolm 2020

- Born in Gur i Hasit near Prizren about 1630, Bogdani was educated in the traditions of the Catholic Church, to which he devoted all his energy. Historical Dictionary of Kosovo, Robert Elsie, Scarecrow Press, 2010, p. 46., ISBN 0810874830

- He further notes the villages Gur, Shegjeç and Zogaj, whose exact location is not known, but which most probably lie in the vicinity of Gjakova and Prizren in the Has region. Conflicting Loyalties in the Balkans: The Great Powers, the Ottoman Empire and Nation-Building, Hannes Grandits, Nathalie Clayer, Robert Pichler, I.B.Tauris, 2011, p. 312., ISBN 1848854773

- The Tribes of Albania: History, Society and Culture, Library of Balkan Studies, Robert Elsie, I.B.Tauris, 2015, ISBN 1784534013, p. 279.

- Bartl, Peter (2007). Bardhyl Demiraj (ed.). Pjetër Bogdani und die Anfänge des alb. Buchdrucks. Nach Vier hundert fünfzig Jahren (in German). Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 273. ISBN 9783447054683. Retrieved 26 September 2012.

- Elsie, Robert. The Tribes of Albania: History, Society and Culture. London, I.B. Tauris & Co. Ltd, 2015. s. 279.

- Palnikaj, Mark (2020). Klerikë atdhetarë. Tiranë. p. 32.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Iseni, Bashkim (2008). La question nationale en Europe du Sud-Est: genèse, émergence et développement de l'indentité nationale albanaise au Kosovo et en Macédoine. Peter Lang. p. 114. ISBN 978-3-03911-320-0. Retrieved 21 June 2011.

- Prifti, Peter R.; Prifti, Professor Peter (2005). Unfinished Portrait of a Country. East European Monographs. ISBN 978-0-88033-558-4.

- "Pjetër Bogdani and Europe, at a Symposium in Tirana". Oculus News.

- Bank of Albania. Currency: Banknotes in circulation Archived 2009-02-26 at the Wayback Machine. – Retrieved on 23 March 2009.

External links

- Bogdani at the site Albanian Literature, including the first version of this biography and translated Bogdani's poetry in English.

- Çeta e profetëve by Pjetër Bogdani (1685); link split into two parts (In Old Albanian)

- DE VITA IESU CHRISTI, SALVATORIS MUNDI, ET EIUS EVANGELICA VERITATE, ITALICE ET EPIROTICE CONTEXTA, ... PETRO BOGDANO MACEDONE, SACR. CONGR. DE PROP. FIDE ALUMNO ... ARCHIEPISCOPO SCUPORUM AC TOTIUS REGNI SERVIAE, ... Edition PATAVII, 1685 . In Latin and Albanian.