Cork (material)

Cork is an impermeable buoyant material. It is the phellem layer of bark tissue which is harvested for commercial use primarily from Quercus suber (the cork oak), which is native to southwest Europe and northwest Africa. Cork is composed of suberin, a hydrophobic substance. Because of its impermeable, buoyant, elastic, and fire retardant properties, it is used in a variety of products, the most common of which is wine stoppers.

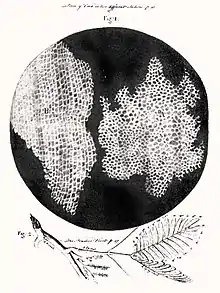

The montado landscape of Portugal produces approximately half of the cork harvested annually worldwide, with Corticeira Amorim being the leading company in the industry.[1] Cork was examined microscopically by Robert Hooke, which led to his discovery and naming of the cell.[2]

Cork composition varies depending on geographic origin, climate and soil conditions, genetic origin, tree dimensions, age (virgin or reproduction), and growth conditions. However, in general, cork is made up of suberin (average of about 40%), lignin (22%), polysaccharides (cellulose and hemicellulose) (18%), extractables (15%) and others.[3]

History

Cork is a natural material used by humanity for over 5,000 years. It is a material whose applications have been known since antiquity, especially in floating devices and as stopper for beverages, mainly wine, whose market, from the early twentieth century, had a massive expansion, particularly due to the development of several cork based agglomerates.[4]

In China, Egypt, Babylon, and Persia from about 3000 BC, cork was already used for sealing containers, fishing equipment, and domestic applications. In ancient Greece (1600 to 1100 years BC) cork was used in footwear, to manufacture a type of sandals attached to the foot by straps, generally leather and with a sole in cork or leather.[5][6]

In the second century AD, a Greek physician, Dioscorides, noted several medical applications of cork, mainly for hair loss treatment.[5] Nowadays, the majority of people know cork for its use as stoppers in wine bottles. Cork stoppers were adopted in 1729 by Ruinart and in 1973 by Moët et Chandon.[3]

Structure

Cork presents a characteristic cellular structure in which the cells have usually a pentagonal or hexagonal shape. The cellular wall consists of a thin, lignin rich middle lamella (internal primary wall), a thick secondary wall made up from alternating suberin and wax lamella, and a thin tertiary wall of polysaccharides. Some studies suggest that the secondary wall is lignified, and therefore, may not consist exclusively of suberin and waxes. The cells of cork are filled with a gas mixture similar to the air, making them behave as authentic "pads," which contributes to the capability of cork to recover after compressed.[3]

Sources

There are about 2,200,000 hectares of cork oak (Quercus suber) forest in the Mediterranean basin, the native area of the species. The most extensively managed habitats are in Portugal (34%) and in Spain (27%). Annual production is about 300,000 tons; 49.6% from Portugal, 30.5% from Spain, 5.8% from Morocco, 4.9% from Algeria, 3.5% from Tunisia, 3.1% from Italy, and 2.6% from France.[7] Once the trees are about 25 years old the cork is traditionally stripped from the trunks every nine years, with the first two harvests generally producing lower quality cork (male cork or virgin cork). The trees live for about 300 years.

The cork industry is generally regarded as environmentally friendly.[8] Cork production is generally considered sustainable because the cork tree is not cut down to obtain cork; only the bark is stripped to harvest the cork.[9] The tree continues to live and grow. The sustainability of production and the easy recycling of cork products and by-products are two of its most distinctive aspects. Cork oak forests also prevent desertification and are a particular habitat in the Iberian Peninsula and the refuge of various endangered species.[10]

Carbon footprint studies conducted by Corticeira Amorim, Oeneo Bouchage of France and the Cork Supply Group of Portugal concluded that cork is the most environmentally friendly wine stopper in comparison to other alternatives. The Corticeira Amorim's study, in particular ("Analysis of the life cycle of Cork, Aluminum and Plastic Wine Closures"), was developed by PricewaterhouseCoopers, according to ISO 14040.[11][12] Results concluded that, concerning the emission of greenhouse gases, each plastic stopper released 10 times more CO2, whilst an aluminium screw cap releases 26 times more CO2 than does a cork stopper. For example, to produce 1,000 cork stoppers 1.5 kg CO2 are emitted, but to produce the same amount of plastic stoppers 14 kg of CO2 are emitted and for the same amount of aluminium screw caps 37 kg CO2 are emitted.[4]

The so called "cork trees" (Phellodendron) are unrelated to the cork oak, they have corky bark but not thick enough for cork production.

Harvesting

Cork is extracted only from early May to late August, when the cork can be separated from the tree without causing permanent damage. When the tree reaches 25–30 years of age and about 24 in (60 cm) in circumference, the cork can be removed for the first time. However, this first harvest almost always produces poor quality or "virgin" cork (Portuguese cortiça virgem; Spanish corcho bornizo or corcho virgen[13]).

The workers who specialize in removing the cork are known as extractors. An extractor uses a very sharp axe to make two types of cuts on the tree: one horizontal cut around the plant, called a crown or necklace, at a height of about 2–3 times the circumference of the tree, and several vertical cuts called rulers or openings. This is the most delicate phase of the work because, even though cutting the cork requires significant force, the extractor must not damage the underlying phellogen or the tree will be harmed.

To free the cork from the tree, the extractor pushes the handle of the axe into the rulers. A good extractor needs to use a firm but precise touch in order to free a large amount of cork without damaging the product or tree.

These freed portions of the cork are called planks. The planks are usually carried off by hand since cork forests are rarely accessible to vehicles. The cork is stacked in piles in the forest or in yards at a factory and traditionally left to dry, after which it can be loaded onto a truck and shipped to a processor.

Bark from initial harvests can be used to make flooring, shoes, insulation and other industrial products. Subsequent extractions usually occur at intervals of 9 years, though it can take up to 13 for the cork to reach an acceptable size. If the product is of high quality it is known as "gentle" cork (Portuguese cortiça amadia,[14] but also cortiça secundeira only if it is the second time; Spanish corcho segundero, also restricted to the "second time"[13]), and, ideally, is used to make stoppers for wine and champagne bottles.[15]

Properties and uses

Cork's elasticity combined with its near-impermeability makes it suitable as a material for bottle stoppers, especially for wine bottles. Cork stoppers represent about 60% of all cork based production. Cork has an almost zero Poisson's ratio, which means the radius of a cork does not change significantly when squeezed or pulled.[16]

Cork is an excellent gasket material. Some carburetor float bowl gaskets are made of cork, for example.

Cork is also an essential element in the production of badminton shuttlecocks.

Cork's bubble-form structure and natural fire retardant make it suitable for acoustic and thermal insulation in house walls, floors, ceilings, and facades. The by-product of more lucrative stopper production, corkboard, is gaining popularity as a non-allergenic, easy-to-handle and safe alternative to petrochemical-based insulation products.

Sheets of cork, also often the by-product of stopper production, are used to make bulletin boards as well as floor and wall tiles.

Cork's low density makes it a suitable material for fishing floats and buoys, as well as handles for fishing rods (as an alternative to neoprene).

Granules of cork can also be mixed into concrete. The composites made by mixing cork granules and cement have lower thermal conductivity, lower density, and good energy absorption. Some of the property ranges of the composites are density (400–1500 kg/m3), compressive strength (1–26 MPa), and flexural strength (0.5–4.0 MPa).[17]

Use in wine bottling

As late as the mid-17th century, French vintners did not use cork stoppers, using instead oil-soaked rags stuffed into the necks of bottles.[18]

Wine corks can be made of either a single piece of cork, or composed of particles, as in champagne corks; corks made of granular particles are called "agglomerated corks".[19]

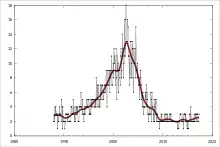

Natural cork closures are used for about 80% of the 20 billion bottles of wine produced each year. After a decline in use as wine-stoppers due to the increase in the use of synthetic alternatives, cork wine-stoppers are making a comeback and currently represent approximately 60% of wine-stoppers in 2016.[20]

Because of the cellular structure of cork, it is easily compressed upon insertion into a bottle and will expand to form a tight seal. The interior diameter of the neck of glass bottles tends to be inconsistent, making this ability to seal through variable contraction and expansion an important attribute. However, unavoidable natural flaws, channels, and cracks in the bark make the cork itself highly inconsistent. In a 2005 closure study, 45% of corks showed gas leakage during pressure testing both from the sides of the cork as well as through the cork body itself.[21]

Since the mid-1990s, a number of wine brands have switched to alternative wine closures such as plastic stoppers, screw caps, or other closures. During 1972 more than half of the Australian bottled wine went bad due to corking. A great deal of anger and suspicion was directed at Portuguese and Spanish cork suppliers who were suspected of deliberately supplying bad cork to non-EEC wine makers to help prevent cheap imports. Cheaper wine makers developed the aluminium "Stelvin" cap with a polypropylene stopper wad. More expensive wines and carbonated varieties continued to use cork, although much closer attention was paid to the quality. Even so, some high premium makers prefer the Stelvin as it is a guarantee that the wine will be good even after many decades of ageing. Some consumers may have conceptions about screw caps being representative of lower quality wines, due to their cheaper price; however, in Australia, for example, much of the non-sparkling wine production now uses these Stelvin caps as a cork alternative, although some have recently switched back to cork citing issues using screw caps.[22]

The alternatives to cork have both advantages and disadvantages. For example, screwtops are generally considered to offer a trichloroanisole (TCA) free seal, but they also reduce the oxygen transfer rate between the bottle and the atmosphere to almost zero, which can lead to a reduction in the quality of the wine. TCA is the main documented cause of cork taint in wine. However, some in the wine industry say natural cork stoppers are important because they allow oxygen to interact with wine for proper aging, and are best suited for wines purchased with the intent to age.[23]

Stoppers which resemble natural cork very closely can be made by isolating the suberin component of the cork from the undesirable lignin, mixing it with the same substance used for contact lenses and an adhesive, and molding it into a standardized product, free of TCA or other undesirable substances.[24] Composite corks with real cork veneers are used in cheaper wines.[25] Celebrated Australian wine writer and critic James Halliday has written that since a cork placed inside the neck of a wine bottle is 350-year-old technology, it is logical to explore other more modern and precise methods of keeping wine safe.[26]

The study "Analysis of the life cycle of Cork, Aluminum and Plastic Wine Closures," conducted by PricewaterhouseCoopers and commissioned by a major cork manufacturer, Amorim, concluded that cork is the most environmentally responsible stopper, in a one-year life cycle analysis comparison with plastic stoppers and aluminum screw caps.[27][28]

Other uses

- On 28 November 2007, the Portuguese national postal service CTT issued the world's first postage stamp made of cork.[29][30]

- In musical instruments, particularly woodwind instruments, where it is used to fasten together segments of the instrument, making the seams airtight. Low quality conducting baton handles are also often made out of cork.

- In shoes, especially those using welt construction to improve climate control and comfort.

- Because it is impermeable and moisture-resistant, cork is often used as an alternative to leather in handbags, wallets, and other fashion items.

- To make bricks for the outer walls of houses, as in Portugal's pavilion at Expo 2000.

- As the core of both baseballs and cricket balls. A corked bat is made by replacing the interior of a baseball bat with cork – a practice known as "corking". It was historically a method of cheating at baseball; the efficacy of the practice is now discredited.

- In various forms, in spacecraft heat shields[31] and fairings.

- In the paper pick-up mechanisms in inkjet and laser printers.

- To make later-model pith helmets.[32]

- Hung from hats to keep insects away. (See cork hat)

- As a core material in sandwich composite construction.

- As the friction lining material of an automatic transmission clutch, as designed in certain mopeds.

- Alternative of wood or aluminium in automotive interiors.[33]

- Cork slabs are sometimes used by orchid growers as a natural mounting material.

- Cork paddles are used by glass blowers to manipulate and shape hot molten glass.

- Many racing bicycles have their handlebars wrapped in cork-based tape manufactured in a variety of colors.

- To make architectural models.

Notes

- Calheiros, J. L.; Meneses, E. "The cork industry in Portugal". Junta Nacional da Cortiça, Portugal. Archived from the original on 12 January 2012.

- "Robert Hooke (1635-1703)". UC Museum of Paleontology @ UC Berkeley. Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- Duarte, Ana Paula; Bordado, João Carlos (2015). "Cork – A Renewable Raw Material: Forecast of Industrial Potential and Development Priorities". Frontiers in Materials. 2: 2. Bibcode:2015FrMat...2....2D. doi:10.3389/fmats.2015.00002. ISSN 2296-8016.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. - Gil, Luís (11 April 2014). "Cork: a strategic material". Frontiers in Chemistry. 2: 16. Bibcode:2014FrCh....2...16G. doi:10.3389/fchem.2014.00016. ISSN 2296-2646. PMC 3990040. PMID 24790984.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. - "Cork: culture, nature, future". Santa Maria de Lamas: Press Release. APCOR Cork Information Bureau (Facebook: CorkInWorld). 2010. Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- Duarte, Ana Paula; Bordado, João Carlos (2 February 2015). "Cork – a renewable raw material: forecast of industrial potential and development priorities". Frontiers in Materials. 2: 2. Bibcode:2015FrMat...2....2D. doi:10.3389/fmats.2015.00002.

- "Cork Oak Forest (formerly titled: Cork Production – Area of cork oak forest)". apcor.pt. APCOR. Archived from the original on 18 March 2015. Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- Skidmore, Sarah (26 August 2007). "Stopper pulled on cork debate". USA Today (AP).

- McClellan, Keith. "Apples, Corks, and Age". Blanco County News. Archived from the original on 27 December 2014. Retrieved 22 May 2014.

- Henley, Paul (18 September 2008). "Urging vintners to put a cork in it". BBC News.

- "Analysis of the life cycle of Cork, Aluminium and Plastic Wine Closures" (PDF). Corticeira Amorim (by PwC/ECOBILAN). October 2008. p. 126. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 September 2009.

- "Analysis of the life cycle of Cork, Aluminium and Plastic Wine Closures (summary)" (PDF). Porto Protocol Foundation. Corticeira Amorim (by PwC/ECOBILAN). November 2008. p. 27. Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- "DRAE". Lema.rae.es. Archived from the original on 4 November 2015. Retrieved 3 July 2014.

- Amadio comes from and is synonym of amavio, "beberage or spell to seduce" (Dicionário Houaiss da Língua Portuguesa), from amar, "to love".

- "Harvesting Cork Is as Natural as Shearing Sheep". Newsusa.com. 100percentcork.org. 12 June 2014. Archived from the original on 13 June 2014. Retrieved 16 July 2014.

- Stavroulakis, G.E. (2005). "Auxetic behaviour: Appearance and engineering applications". Physica Status Solidi B. 242 (3): 710–720. Bibcode:2005PSSBR.242..710S. doi:10.1002/pssb.200460388. S2CID 122613228.

- Karade SR. 2003. An Investigation of Cork Cement Composites. PhD Thesis. BCUC. Brunel University, UK.

- Prlewe, J. Wine From Grape to Glass. New York: Abbeville Press, 1999, p. 110.

- "Guide for using wine corks". Archived from the original on 13 January 2014.

- "International Organisation of Vine and Wine".

- Gibson, Richard (24 June 2005). "variability in permeability of corks and closures" (PDF). American Society for Enology and Viticulture. Scorpex Wine Services. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 May 2013.

- "Rusden Wines abandons screwcap for cork". Harpers.co.uk. Harpers Wine & Spirit. 26 July 2012. Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- "Cork or screw cap – which is best for your wine?". Corklink.com. CorkLink. 8 June 2014. Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- "Diam Corks". Archived from the original on 16 December 2014., The Wine Society

- Konohovs, Artjoms (16 June 2014). "The True Cost of a Bottle of Cheap Wine (2012-03-14)". KALW. Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- Halliday, James. "Wine bottle closures". WineCompanion.com.au. Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- "Evaluation of the environmental impacts of Cork Stoppers versus Aluminium and Plastic Closures: Analysis of the life cycle of Cork, Aluminium and Plastic Wine Closures" (PDF). PwC/ECOBILAN). Corticeira Amorim (Amorim Cork Research). October 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 November 2016. Retrieved 3 April 2016.

- Easton, Sally (8 December 2008). "Cork is the most sustainable form of closure, study finds". Decanter. Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- "CTT lançam primeiro selo de cortiça do mundo (CTT launches the world's first cork stamp "practically sold out")" (in Portuguese). Publico.pt. Archived from the original on 1 October 2011.

- "Corks – They're Not Just For Wine Bottles Anymor: cork stamp debuts in Portugal". Archived from the original on 4 December 2014. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- "Genesis: Search for Origins Spacecraft Subsystems – Sample Return Capsule". Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

cork-based material called SLA-561V that was developed by Lockheed Martin for use on the Viking missions to Mars, and have been used on several missions including Genesis, Pathfinder, Stardust and the Mars Exploration Rover missions.

- Suciu, Peter (17 September 2012). "Pith vs. Cork – Not One and the Same". Militarysunhelmets.com. Military Sun Helmets. Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- Markus, Frank (7 January 2012). "Getting Corked: Faurecia Takes to the Automotive Interior Fashion Runway". Motor Trend. Archived from the original on 27 January 2013. Retrieved 24 January 2013.

References

- Margarida Pi i Contallé. 2006. Laboratory head in Manuel Serra Hongos y micotoxinas en tapones de corcho. Propuesta de límites micológicos aceptables

- Cork production corkfacts.com

- Instituto de Promoción del Corcho, Extremadura iprocor.org (in Spanish)

- Analysis of the life cycle of Cork, Aluminium and Plastic Wine Closures

- Henley, Paul, BBC.com (18 September 2008). "Urging vintners to put a cork in it".

- PricewaterhouseCoopers/ECOBILAN (October 2008). Analysis of the life cycle of Cork, Aluminium and Plastic Wine Closures

- Cork - Forest in a Bottle. 2008.

External links

- Cork Quality Council

- Book review: To cork or not to cork

- Material Properties Data: Cork

- Cork Recycling Initiative. 2017.