Petra

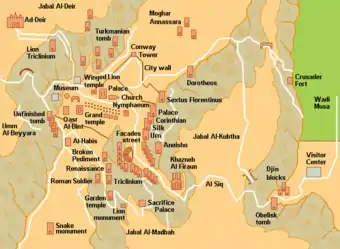

Petra (Arabic: ٱلْبَتْراء, romanized: Al-Batraʾ; Greek: Πέτρα, "Rock"), originally known to its inhabitants as Raqmu or Raqēmō[3][4] (Nabataean: 𐢛𐢚𐢒 or 𐢛𐢚𐢓𐢈, *Raqēmō), is a historic and archaeological city in southern Jordan. Famous for its rock-cut architecture and water conduit system, Petra is also called the "Rose City" because of the colour of the stone from which it is carved;[5] it was famously called "a rose-red city half as old as time" in a poem of 1845 by John Burgon. It is adjacent to the mountain of Jabal Al-Madbah, in a basin surrounded by mountains forming the eastern flank of the Arabah valley running from the Dead Sea to the Gulf of Aqaba.[6] Access to the city is through a famously picturesque 1.2-kilometre-long (3⁄4 mi) gorge called the Siq, which leads directly to the Khazneh.

| Petra (𐢛𐢚𐢓𐢈) | |

|---|---|

From top, left to right: the Urn Tombs, en-Nejr theatre, Al-Khazneh (Treasury), Qasr al-Bint temple and view of Ad Deir (Monastery) trail | |

| Location | Ma'an Governorate, Jordan |

| Coordinates | 30°19′43″N 35°26′31″E |

| Area | 264 km2 (102 sq mi)[1] |

| Elevation | 810 m (2,657 ft) |

| Built | Possibly as early as the 5th century BC[2] |

| Visitors | 1,135,300 (in 2019) |

| Governing body | Petra Region Authority |

| Website | www |

Location of Petra (𐢛𐢚𐢓𐢈) in Jordan | |

| Criteria | Cultural: i, iii, iv |

| Reference | 326 |

| Inscription | 1985 (9th Session) |

The area around Petra has been inhabited from as early as 7000 BC,[7] and the Nabataeans might have settled in what would become the capital city of their kingdom as early as the 4th century BC.[8] Archaeological work has only discovered evidence of Nabataean presence dating back to the second century BC,[9] by which time Petra had become their capital.[7] The Nabataeans were nomadic Arabs who invested in Petra's proximity to the incense trade routes by establishing it as a major regional trading hub.[7][10]

The trading business gained the Nabataeans considerable revenue and Petra became the focus of their wealth. Unlike their enemies, the Nabataeans were accustomed to living in the barren deserts and were able to repel attacks by taking advantage of the area's mountainous terrain. They were particularly skillful in harvesting rainwater, agriculture, and stone carving. Petra flourished in the 1st century AD, when its Al-Khazneh structure, possibly the mausoleum of Nabataean king Aretas IV, was constructed, and its population peaked at an estimated 20,000 inhabitants.[11] Most of the famous rock-cut buildings, which are mainly tombs, date from this and the following period. Much less remains of the free-standing buildings of the city.

Although the Nabataean kingdom became a client state of the Roman Empire in the first century BC, it was only in 106 AD that it lost its independence. Petra fell to the Romans, who annexed Nabataea and renamed it as Arabia Petraea.[12] Petra's importance declined as sea trade routes emerged, and after an earthquake in 363 destroyed many structures. In the Byzantine era, several Christian churches were built, but the city continued to decline and, by the early Islamic era, it was abandoned except for a handful of nomads. It remained unknown to the western world until 1812, when Swiss traveller Johann Ludwig Burckhardt rediscovered it.[13]

It has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1985. UNESCO has described Petra as "one of the most precious cultural properties of man's cultural heritage".[14] In 2007, Petra was voted one of the New 7 Wonders of the World.[15] Petra is a symbol of Jordan, as well as Jordan's most-visited tourist attraction. Tourist numbers peaked at 1.1 million in 2019, marking the first time that the figure rose above the 1 million mark.[16] Tourism in the historical city was hit hard by the COVID-19 pandemic, but soon after started to pick up again, reaching 905,000 visitors in 2022.[17]

History

Neolithic

By 7000 BC, some of the earliest recorded farmers had settled in Beidha, a Pre-Pottery Neolithic settlement just north of Petra.[7]

Bronze Age

Petra is listed in Egyptian campaign accounts and the Amarna letters as Pel, Sela, or Seir.[18]

Iron Age Edom

The Iron Age lasted between 1200 and 600 BC; in that time, the Petra area was occupied by the Edomites. This came when the Edomites rebelled after the death of King Solomon in 928 BC when Israel split into two kingdoms for Israel to be in the north and Judah in the south. The Edomites were known as descendents of Esau and this was referenced in the Old Testament of the Bible.[19] The configuration of mountains in Petra allowed for a reservoir of water for the Edomites. This made Petra a stopping ground for merchants, making it an outstanding area for trade. Things that were traded here included wines, olive oil, and wood.

Initially, the Edomites were accompanied by Nomads who eventually left, but the Edomites stayed and made their mark on Petra before the emergence of the Nabataens. They were then engaged in battle with King Amaziah of Judah and chased back into their own lands. It is said that 10,000 men were thrown off of the mountain Umm el-Biyara, but this story has been debated by scholars.[20]

The Edomite site excavated at the top of the Umm el-Biyara mountain at Petra was established no earlier than the seventh century BC (Iron II).[21]

Emergence of Petra

The Nabataeans were one among several nomadic Bedouin tribes that roamed the Arabian Desert and moved with their herds to wherever they could find pasture and water.[8] Although the Nabataeans were initially embedded in Aramaic culture, theories about them having Aramean roots are rejected by many modern scholars. Instead, archaeological, religious and linguistic evidence confirm that they are a northern Arabian tribe.[22] Current evidence suggests that the Nabataean name for Petra was Raqēmō, variously spelled in inscriptions as rqmw or rqm.[4]

The Jewish historian Josephus (ca. 37–100 AD) writes that the region was inhabited by the Midianites during the time of Moses, and that they were ruled by five kings, one of whom was Rekem. Josephus mentions that the city, called Petra by the Greeks, "ranks highest in the land of the Arabs" and was still called Rekeme by all the Arabs of his time, after its royal founder (Antiquities iv. 7, 1; 4, 7).[23] The Onomasticon of Eusebius also identified Rekem as Petra.[24] Arabic raqama means "to mark, to decorate", so Rekeme could be a Nabataean word referring to the famous carved rock façades. In 1964, workmen clearing rubble away from the cliff at the entrance to the gorge found several funerary inscriptions in Nabatean script. One of them was to a certain Petraios who was born in Raqmu (Rekem) and buried in Garshu (Jerash).[25][26]

An old theory held that Petra might be identified with a place called sela in the Hebrew Bible. Encyclopædia Britannica (1911) states that the Semitic name of the city, if not Sela, would remain unknown. It nevertheless cautioned that sela simply means "rock" in Hebrew, and thence might not be identified with a city where it occurs in the biblical text in the book of Obadiah. It is possible that the city was part of the nation of Edom. [6]

The passage in Diodorus Siculus (xix. 94–97) which describes the expeditions which Antigonus sent against the Nabataeans in 312 BC, was understood by some researchers to throw some light upon the history of Petra, but the "petra" (Greek for rock) referred to as a natural fortress and place of refuge cannot be a proper name, and the description implies that there was no town in existence there at the time.[6][27]

Roman period

In AD 106, when Cornelius Palma was governor of Syria, the part of Arabia under the rule of Petra was absorbed into the Roman Empire as part of Arabia Petraea, and Petra became its capital.[28] The native dynasty came to an end but the city continued to flourish under Roman rule. It was around this time that the Petra Roman Road was built. A century later, in the time of Alexander Severus, when the city was at the height of its splendor, the issue of coinage came to an end. There was no more building of sumptuous tombs, owing apparently to some sudden catastrophe, such as an invasion by the neo-Persian power under the Sassanid Empire.[6]

Meanwhile, as Palmyra (fl. 130–270) grew in importance and attracted the Arabian trade away from Petra, the latter declined. It appears, however, to have lingered on as a religious center. Another Roman road was constructed at the site. Epiphanius of Salamis (c.315–403) writes that in his time a feast was held there on December 25 in honor of the virgin Khaabou (Chaabou) and her offspring Dushara.[6] Dushara and al-Uzza were two of the main deities of the city, which otherwise included many idols from other Nabataean deities such as Allat and Manat.[29]

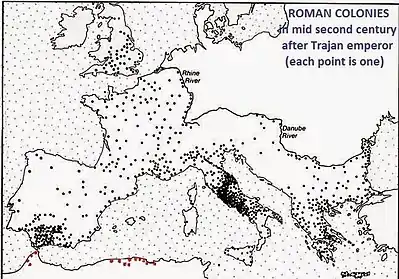

Between 111 and 114 Trajan built the Via Traiana Nova, running from the Syrian border to the Red Sea through Petra. This road followed the old routes of Nabataean caravans. In the shadow of the Pax Romana, this route revived trade between Arabia, Syria, and Mediterranean harbors. In 125 AD, one of Emperor Hadrian's administrators left marks in Petra, pointed out by documents found at the Dead Sea. In 130 AD, Hadrian visited the former Nabataean capital, giving it the name of Hadriānī Petra Metropolis, imprinted on his coins. His visit, however, did not lead to any boom in development and new buildings as it did in Jerash. The province's governor, Sextius Florentinus, erected a monumental mausoleum for his son near the end of the al-Hubta (King's Wall) tombs, which had been generally reserved during the Nabataean period for the royal family.

The interest that Roman emperors showed in the city in the 3rd century suggests that Petra and its environs remained highly esteemed for a long time. An inscription to Liber Pater, a god revered by Emperor Septimius Severus, was found in the temenos of the temple known as Qasr al-Bint, and Nabataean tombs contained silver coins with the emperor's portrait, as well as pottery from his reign. Emperor Elagabalus declared Petra to be a Roman colony, when he reorganized the Roman Empire towards the end of the 3rd century.[30] The area from Petra to Wadi Mujib, the Negev, and the Sinai Peninsula were annexed into the province of Palaestina Salutaris. Petra may be seen on the Madaba mosaic map from the reign of Emperor Justinian.

Byzantine period

.jpg.webp)

Petra declined rapidly under Roman rule, in large part from the revision of sea-based trade routes. In 363, an earthquake destroyed many buildings and crippled the vital water management system.[31] The old city of Petra was the capital of the Byzantine province of Palaestina III and many churches from the Byzantine period were excavated in and around Petra. In one of them, the Byzantine Church, 140 papyri were discovered, which contained mainly contracts dated from 530s to 590s, establishing that the city was still flourishing in the 6th century.[32] The Byzantine Church is a prime example of monumental architecture in Byzantine Petra.

The last reference to Byzantine Petra comes from the Spiritual Meadow of John Moschus, written in the first decades of the 7th century. He gives an anecdote about its bishop, Athenogenes. It ceased to be a metropolitan bishopric sometime before 687 when that function had been transferred to Areopolis. Petra is not mentioned in the narratives of the Muslim conquest of the Levant, nor does it appear in any early Islamic records.[33]

Crusaders and Mamluks

In the 12th century, the Crusaders built fortresses such as the Alwaeira Castle, but were forced to abandon Petra after a while. As a result, the location of Petra was lost until the 19th century.[34][35]

Two further Crusader-period castles are known in and around Petra: the first is al-Wu'ayra, situated just north of Wadi Musa. It can be viewed from the road to Little Petra. It is the castle that was seized by a band of Turks with the help of local Muslims and only recovered by the Crusaders after they began to destroy the olive trees of Wadi Musa. The potential loss of livelihood led the locals to negotiate a surrender. The second is on the summit of el-Habis, in the heart of Petra, and can be accessed from the West side of the Qasr al-Bint.

The ruins of Petra were an object of curiosity during the Middle Ages and were visited by Baibars, one of the first Mamluk sultans of Egypt, towards the end of the 13th century.[6]

19th and 20th centuries

The first European to describe them was the Swiss traveler Johann Ludwig Burckhardt during his travels in 1812.[6][36] At that time, the Greek Church of Jerusalem operated a diocese in Al Karak named Battra (باطره in Arabic, and Πέτρας in Greek) and it was the opinion among the clergy of Jerusalem that Kerak was the ancient city of Petra.[36]

Burckhardt already spoke Arabic fluently, and was on his way to explore the Niger River when he heard stories of a dead city that held the tomb of the Prophet Aaron, and became fascinated with finding the city. He then dressed himself up as a local, and only spoke in Arabic, bringing a goat with him with the intent of sacrificing it in honor of Aaron's Tomb. After one day of exploring, he was convinced that he had found the lost city of Petra.[37]

Léon de Laborde and Louis-Maurice-Adolphe Linant de Bellefonds made the first accurate drawings of Petra in 1828.[38] The Scottish painter David Roberts visited Petra in 1839 and returned to Britain with sketches and stories of the encounter with local tribes, published in The Holy Land, Syria, Idumea, Arabia, Egypt, and Nubia. Frederic Edwin Church, the leading American landscape painter of the 19th century, visited Petra in 1868, and the resulting painting El Khasné, Petra is among his most important and well-documented.[38] Missionary Archibald Forder published photographs of Petra in the December 1909 issue of National Geographic.

.jpg.webp)

Because the structures weakened with age, many of the tombs became vulnerable to thieves, and many treasures were stolen. In 1929, a four-person team consisting of British archaeologists Agnes Conway and George Horsfield, Palestinian physician and folklore expert Dr Tawfiq Canaan and Dr Ditlef Nielsen, a Danish scholar, excavated and surveyed Petra.[39]

The archaeologist Philip Hammond from the University of Utah visited Petra for nearly 40 years. He explained that the local folklore says it was created by the wand of Moses, when he struck the rock to bring forth water for the Israelites. Hammond believed the carved channels deep within the walls and ground were made from ceramic pipes that once fed water for the city, from rock-cut systems on the canyon rim.[40]

Numerous scrolls in Greek and dating to the Byzantine period were discovered in an excavated church near the Temple of the Winged Lions in Petra in December 1993.[41]

21st century

In December 2022, Petra was hit by heavy flooding.[42]

Layout

Excavations have demonstrated that it was the ability of the Nabataeans to control the water supply that led to the rise of the desert city, creating an artificial oasis. The area is visited by flash floods, but archaeological evidence shows that the Nabataeans controlled these floods by the use of dams, cisterns, and water conduits. These innovations stored water for prolonged periods of drought and enabled the city to prosper from its sale.[43][44]

In ancient times, Petra might have been approached from the south on a track leading across the plain of Petra, around Jabal Haroun ("Aaron's Mountain"), the location of the Tomb of Aaron, said to be the burial place of Aaron, brother of Moses. Another approach was possibly from the high plateau to the north. Today, most modern visitors approach the site from the east. The impressive eastern entrance leads steeply down through a dark, narrow gorge, in places only 3–4 m (10–13 ft) wide, called the Siq ("shaft"), a natural geological feature formed from a deep split in the sandstone rocks and serving as a waterway flowing into Wadi Musa.[45]

Hellenistic architecture

Petra is known primarily for its Hellenistic architecture. The facades of the tombs in Petra are commonly rendered in Hellenistic style, reflecting the number of diverse cultures which the Nabataens traded, all of which were in turn influenced by Greek culture. Most of these tombs contain small burials niches carved into the stone.[46]

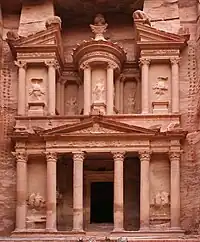

Perhaps the best example of the Hellenistic style is seen in the Treasury, which is 24 meters (79 ft) wide and 37 meters (121 ft) tall and references the architecture of Alexandria.[47] The facade of the Treasury features a broken pediment with a central tholos inside, and two obelisks appear to form into the rock at the top. Near the bottom of the Treasury are the twin Greek gods Castor and Pollux, who protect travellers on their journeys. Near the top of the Treasury, two victories are seen standing on each side of a female figure on the tholos. This female figure is believed to be the Isis-Tyche, Isis and Tyche being the Egyptian and Greek goddesses, respectively, of good fortune.[46]

Another prime example of Hellenistic architecture featured in Petra is its Monastery, which stands at 45 meters (148 ft) tall and 50 meters (160 ft) wide; this is Petra's largest monument and is similarly carved into the rock face. The facade of this again features a broken pediment, similar to the Treasury, as well as another central tholos. The Monastery displays more of a Nabataen touch while at the same time incorporating elements from Greek architecture.[46] Its only source of light is its entrance standing at 8 meters (26 ft) high. There is a large space outside of the Monastery, which is purposefully flattened for worship purposes. Formerly, in the Byzantine period, this was a place for Christian worship, but is now a holy site for pilgrims to visit.

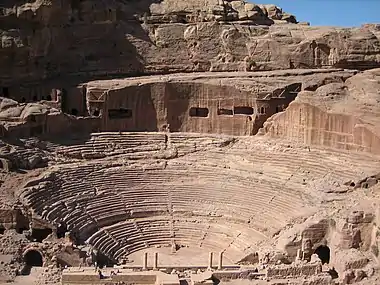

City centre

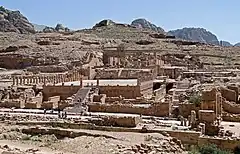

At the end of the narrow gorge, the Siq, stands Petra's most elaborate ruin, popularly known as Al-Khazneh ("the Treasury"), hewn into the sandstone cliff. While remaining in remarkably preserved condition, the face of the structure is marked by hundreds of bullet holes made by the local Bedouin tribes that hoped to dislodge riches that were once rumoured to be hidden within it.[45] A little farther from the Treasury, at the foot of the mountain called en-Nejr, is a massive theatre, positioned so as to bring the greatest number of tombs within view. At the point where the valley opens out into the plain, the site of the city is revealed with striking effect. The theatre was cut into the hillside and into several of the tombs during its construction. Rectangular gaps in the seating are still visible. Almost enclosing it on three sides are rose-coloured mountain walls, divided into groups by deep fissures and lined with knobs cut from the rock in the form of towers.[6] The theatre was said to hold around 8,500 people.[48] The performances that audiences were able to attend here were poetry readings and dramas. Gladiator fights were also said to be held here and attracted the most audience, although no gladiator was able to gain any momentum or fame due to the heavy mortality rate that came with it. The theatre was one of many structures in Petra that took significant damage due to the 363 Galilee earthquake.[48]

The Petra Pool and Garden Complex is a series of structures within the city center. Originally said to be a market area,[49] excavations at the site have allowed scholars to identify it as an elaborate Nabataean garden, which included a large swimming pool, an island-pavilion, and an intricate hydraulic system.[50][51][52]

Ahead of the Petra Pool and Garden Complex lies Colonnaded street, which is among few artifacts of Petra that was constructed rather than natural. This street used to hold a semi-circle nymphaeum, which is now in ruins due to flash flooding, and used to hold Petra's only tree. This was intended to be a symbol for the peaceful atmosphere that the Nabataens were able to construct in Petra. Once the Romans took control of the city, Colonnaded street was narrowed to make room for a side walk, and 72 columns were added to each side.[53]

High Place of Sacrifice

The High Place of Sacrifice is located at the top of Jebel Madbah Mountain.[54] The beginning of the hike is near Petra's theatre. From there, the site of The High Place of Sacrifice is around an 800-step hike. One commonly believed sacrifice that took place there was libation. Another common form of sacrifice that took place there was animal sacrifice; this is due to the belief that the tomb of the Prophet Aaron is located in Petra, which is a sacred site for Muslims. In honor of this, a goat was sacrificed annually. Other rituals also took place there, including the burning of frankincense.[55]

Royal Tombs

The Royal Tombs of Petra are in the Nabatean version of Hellenistic architecture, but their facades have worn due to natural decay. One of these tombs, the Palace Tomb, is speculated to be the tomb for the kings of Petra. The Corinthian Tomb, which is right next to the Palace Tomb, has the same Hellenistic architecture featured on the Treasury. The two other Royal Tombs are the Silk Tomb and the Urn Tomb; the Silk Tomb does not stand out as much as the Urn Tomb. The Urn Tomb features a large yard in its front, and was turned into a church in 446 AD after the expansion of Christianity.[56]

Exterior platform

In 2016, archaeologists using satellite imagery and drones discovered a very large, previously unknown monumental structure whose beginnings were tentatively dated to about 150 BC, the time when the Nabataeans initiated their public building programme. It is located outside the main area of the city, at the foot of Jabal an-Nmayr and about 0.5 mi (0.8 km) south of the city centre, but is facing east, not towards the city, and has no visible relationship to it. The structure consists of a huge, 184 by 161 ft (56 by 49 m) platform, with a monumental staircase along its eastern side. The large platform enclosed a slightly smaller one, topped with a comparatively small building, 28 by 28 ft (8.5 by 8.5 m), which was facing east toward the staircase. The structure, second in size only to the Monastery complex, probably had a ceremonial function of which not even a speculative explanation has yet been offered by the researchers.[57][58][59]

Religious importance

Pliny the Elder and other writers identify Petra as the capital of the Nabataean Kingdom and the centre of their caravan trade. Enclosed by towering rocks and watered by a perennial stream, Petra not only possessed the advantages of a fortress, but controlled the main commercial routes which passed through it to Gaza in the west, to Bosra and Damascus in the north, to Aqaba and Leuce Come on the Red Sea, and across the desert to the Persian Gulf.[6]

The Nabataeans worshipped Arab gods and goddesses during the pre-Islamic era as well as a few of their deified kings. One, Obodas I, was deified after his death. Dushara was the primary male god accompanied by his three female deities: Al-‘Uzzā, Allat and Manāt. Many statues carved in the rock depict these gods and goddesses. New evidence indicates that broader Edomite, and Nabataean theology had strong links to Earth-Sun relationships, often manifested in the orientation of prominent Petra structures to equinox and solstice sunrises and sunsets.[60]

A stele dedicated to Qos-Allah 'Qos is Allah' or 'Qos the god', by Qosmilk (melech: king) is found at Petra (Glueck 516). Qos is identifiable with Kaush (Qaush) the God of the older Edomites. The stele is horned and the seal from the Edomite Tawilan near Petra identified with Kaush displays a star and crescent (Browning 28), both consistent with a moon deity. It is conceivable that the latter could have resulted from trade with Harran (Bartlett 194). There is continuing debate about the nature of Qos (qaus: bow) who has been identified both with a hunting bow (hunting god) and a rainbow (weather god) although the crescent above the stele is also a bow.

Nabataean inscriptions in Sinai and other places display widespread references to names including Allah, El and Allat (god and goddess), with regional references to al-Uzza, Baal and Manutu (Manat) (Negev 11). Allat is also found in Sinai in South Arabian language. Allah occurs particularly as Garm-'allahi: "god decided" (Greek Garamelos) and Aush-allahi: "gods covenant" (Greek Ausallos). We find both Shalm-lahi "Allah is peace" and Shalm-allat, "the peace of the goddess". We also find Amat-allahi "she-servant of god" and Halaf-llahi "the successor of Allah".[61]

Recently, Petra has been put forward as the original direction of Muslim prayer, the Qibla, by some in the revisionist school of Islamic studies, namely that the earliest mosques faced Petra, not Jerusalem or Mecca.[62] However, others have challenged the notion of comparing modern readings of Qiblah directions to early mosques’ Qiblahs as they claim early Muslims could not accurately calculate the direction of the Qiblah to Mecca and so the apparent pinpointing of Petra by some early mosques may well be coincidental.[63]

The Monastery, Petra's largest monument, dates from the 1st century BC. It was dedicated to Obodas I and is believed to be the symposium of Obodas the god. This information is inscribed on the ruins of the Monastery (the name is the translation of the Arabic Ad Deir).

The Temple of the Winged Lions is a large temple complex dated to the reign of King Aretas IV (9 BC–40 AD). The temple is located in Petra's so-called Sacred Quarter, an area situated at the end of Petra's main Colonnaded Street consisting of two majestic temples, the Qasr al-Bint and, opposite, the Temple of the Winged Lions on the northern bank of Wadi Musa.

Christianity found its way to Petra in the 4th century AD, nearly 500 years after the establishment of Petra as a trade centre. The start of Christianity in Petra started primarily in 330 AD when the first Christian Emperor of Rome took over, Constantine I, otherwise known as Constantine The Great. He began the initial spread of Christianity throughout the Roman Empire. Athanasius mentions a bishop of Petra (Anhioch. 10) named Asterius. At least one of the tombs (the "tomb with the urn"?) was used as a church. An inscription in red paint records its consecration "in the time of the most holy bishop Jason" (447). After the Islamic conquest of 629–632, Christianity in Petra, as of most of Arabia, gave way to Islam. During the First Crusade Petra was occupied by Baldwin I of the Kingdom of Jerusalem and formed the second fief of the barony of Al Karak (in the lordship of Oultrejordain) with the title Château de la Valée de Moyse or Sela. It remained in the hands of the Franks until 1189.[6] It is still a titular see of the Catholic Church.[64]

According to Arab tradition, Petra is the spot where Musa (Moses) struck a rock with his staff and water came forth, and where Moses' brother, Harun (Aaron), is buried, at Mount Hor, known today as Jabal Haroun or Mount Aaron. The Wadi Musa or "Wadi of Moses" is the Arab name for the narrow valley at the head of which Petra is sited. A mountaintop shrine of Moses' sister Miriam was still shown to pilgrims at the time of Jerome in the 4th century, but its location has not been identified since.[65]

Climate

In Petra, there is a semi-arid climate. Most rain falls in the winter. The Köppen-Geiger climate classification is BSk. The average annual temperature in Petra is 15.5 °C (59.9 °F). About 193 mm (7.60 in) of precipitation falls annually.

| Climate data for Petra | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 11.0 (51.8) |

13.1 (55.6) |

16.6 (61.9) |

20.9 (69.6) |

25.1 (77.2) |

28.6 (83.5) |

29.8 (85.6) |

30.0 (86.0) |

28.1 (82.6) |

24.6 (76.3) |

18.2 (64.8) |

13.4 (56.1) |

21.6 (70.9) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 2.2 (36.0) |

2.8 (37.0) |

5.6 (42.1) |

8.7 (47.7) |

11.7 (53.1) |

14.1 (57.4) |

16.1 (61.0) |

16.5 (61.7) |

14.2 (57.6) |

11.2 (52.2) |

7.1 (44.8) |

3.4 (38.1) |

9.5 (49.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 45 (1.8) |

38 (1.5) |

36 (1.4) |

12 (0.5) |

4 (0.2) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

2 (0.1) |

15 (0.6) |

41 (1.6) |

193 (7.6) |

| Source: Climate-Data.org, Climate data | |||||||||||||

Conservation

The Bidoul/Bidul (Petra Bedouin) were forcibly resettled from their cave dwellings in Petra to Umm Sayhoun/Um Seihun by the Jordanian government in 1985, prior to the UNESCO designation process. They were provided with block-built housing with some infrastructure including in particular a sewage and drainage system. Among the six communities in the Petra Region, Umm Sayhoun is one of the smaller communities. The village of Wadi Musa is the largest in the area, inhabited largely by the Layathnah Bedouin, and is now the closest settlement to the visitor centre, the main entrance via the Siq and the archaeological site generally. Umm Sayhoun gives access to the 'back route' into the site, the Wadi Turkmaniyeh pedestrian route.[66]

On December 6, 1985, Petra was designated a World Heritage Site. In a popular poll in 2007, it was also named one of the New 7 Wonders of the World. The Petra Archaeological Park (PAP) became an autonomous legal entity over the management of this site in August 2007.[67]

The Bidouls belong to one of the Bedouin tribes whose cultural heritage and traditional skills were proclaimed by UNESCO on the Intangible Cultural Heritage List in 2005 and inscribed[68] in 2008.

In 2011, following an 11-month project planning phase, the Petra Development and Tourism Region Authority in association with DesignWorkshop and JCP s.r.l published a Strategic Master Plan that guides planned development of the Petra Region. This is intended to guide planned development of the Petra Region in an efficient, balanced and sustainable way over the next 20 years for the benefit of the local population and of Jordan in general. As part of this, a Strategic Plan was developed for Umm Sayhoun and surrounding areas.[69]

The process of developing the Strategic Plan considered the area's needs from five points of view:

- A socio-economic perspective

- The perspective of Petra Archaeological Park

- The perspective of Petra's tourism product

- A land use perspective

- An environmental perspective

The site suffers from a host of threats, including collapse of ancient structures, erosion due to flooding and improper rainwater drainage, weathering from salt upwelling,[70] improper restoration of ancient structures, and unsustainable tourism.[71] The last has increased substantially, especially since the site received widespread media coverage in 2007 during the New7Wonders of the World Internet and cellphone campaign.[72]

In an attempt to reduce the problems, the Petra National Trust (PNT) was established in 1989. It has worked with numerous local and international organisations on projects that promote the protection, conservation, and preservation of the Petra site.[73] Moreover, UNESCO and ICOMOS recently collaborated to publish their first book on human and natural threats to the sensitive World Heritage sites. They chose Petra as its first and the most important example of threatened landscapes. The presentation Tourism and Archaeological Heritage Management at Petra: Driver to Development or Destruction? (2012) was the first in a series to address the very nature of these deteriorating buildings, cities, sites, and regions.[74]

People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) released a video in 2018 highlighting the abuse of working animals in Petra. PETA claimed that animals are forced to carry tourists or pull carriages every day. The video showed handlers beating and whipping working animals, with beatings intensifying when animals faltered. PETA also showed some wounded animals, including camels with fly-infested, open wounds.[75] The Jordanian authority running the site responded by proposing a veterinary clinic, and by undertaking to spread awareness among animal handlers.[76] In 2020, more video released by PETA indicated that conditions for the animals had not improved and, in 2021, the organization was running what appeared to be the only veterinary clinic in the area.[77][78]

Petra is a site at the intersection of natural and cultural heritage forming a unique cultural landscape. Ever since Johann Ludwig Burckhardt[79] aka Sheikh Ibrahim had re-discovered the ruin city in Petra, Jordan, in 1812, the cultural heritage site has attracted different people who shared an interest in the ancient history and culture of the Nabataeans such as travellers, pilgrims, painters and savants.[80] However, it was not until the late 19th century that the ruins were systematically approached by archaeological researchers.[81] Since then regular archaeological excavations[82] and ongoing research on the Nabataean culture have been part of today's UNESCO world cultural heritage site Petra.[83] Through the excavations in the Petra Archaeological Park an increasing number of Nabataean cultural heritage is being exposed to environmental impact. A central issue is the management of water impacting the built heritage and the rock hewn facades.[84] The large number of discoveries and the exposure of structures and findings demand conservation measures respecting the interlinkage between the natural landscape and cultural heritage, as especially this connection is a central challenge at the UNECSO World Heritage Site.[85]

In recent years different conservation campaigns and projects were established at the cultural heritage site of Petra.[86] The main works first focussed on the entrance situation of the Siq to protect tourists and to facilitate access. Also, different projects for conservation and conservation research were conducted. Following is a list of projects, to be continued.

- 1958 Restoration of the third pillar of the Treasury building (Al-Khazneh). This project was funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID)

- 1974–1990 Conservation work in the excavated area of the Winged Lions Temple

- 1981 Different restoration works by the Department of Antiquities of Jordan[87]

- 1985 Restoration works at the Qasr El Bint Temple by the Department of Antiquities of Jordan[88]

- 1990–1998 Excavation and Conservation of the Byzantine Church by the American Centre of Research (ACOR)

- 1992–2002 Conservation and Restoration Center in Petra CARCIP, German GTZ Project.[85]

- 1993–2000 Excavation, conservation and restoration of the Great Temple, funded by the Brown University, USA.[89]

- 1996 onwards, Restoration of the Siq and rehabilitation of the Siq floor by the Petra National Trust foundet by the Jordanian-Swiss counterpart Fund, the Swiss Agency for Development and the World Monuments Fund.[90]

- 2001 Restoration of the altar in front of the Casr Bint Firaun by UNESCO

- 2003 Development of a conservation and maintenance plan of the ancient drainage systems to protect the rock-cut facades[84]

- 2003–2017 Evaluation of desalination and restoration at the tomb facades[91]

- 2006–2010 Preservation and consolidation of the Wall Paintings in Siq al Barid by the Petra National Trust in cooperation with the Department of Antiquities of Jordan and the Courtauld Institute of Art (London).

- 2009 onwards, renewed effort to preserve and rehabilitate the Winged Lions Temple by The Temple of the Winged Lions Cultural Management (TWLCRM) Initiative, the Petra Archaeological Park (PAP) and the Department of Antiquities of Jordan

- 2016–2019 Characterisation and Conservation of Paintings on Walls and Sculpture from Nabataean Petra "The Petra Painting Conservation Project (PPCP)",[92] funded by the German Research Foundation (Project number 285789434).[93]

Popular culture

- In 1845, British poet John William Burgon won Oxford University's Newdigate Prize for his poem "Petra", containing the description "...a rose-red city half as old as time".

- Petra appeared in the novels Left Behind Series; Appointment with Death; The Eagle in the Sand; The Red Sea Sharks, the nineteenth book in The Adventures of Tintin series; and in Kingsbury's The Moon Goddess and the Son. It played a prominent role in the Marcus Didius Falco mystery novel Last Act in Palmyra, and is the setting for Agatha Christie's Appointment With Death. In Blue Balliett's novel, Chasing Vermeer, the character Petra Andalee is named after the site.[94]

- In 1979 Marguerite van Geldermalsen from New Zealand married Mohammed Abdullah, a Bedouin in Petra.[95] They lived in a cave in Petra until the death of her husband. She authored the book Married to a Bedouin.

- An Englishwoman, Joan Ward, wrote Living With Arabs: Nine Years with the Petra Bedouin[96] documenting her experiences while living in Umm Sayhoun with the Petra Bedouin, covering the period 2004–2013.

- The playwright John Yarbrough's tragicomedy, Petra,[97] debuted at the Manhattan Repertory Theatre in 2014[98] and was followed by award-winning performances at the Hudson Guild in New York in 2015.[99] It was selected for the Best American Short Plays 2014-2015 anthology.[100]

- The site appeared in films such as Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, Arabian Nights, Passion in the Desert, Mortal Kombat Annihilation, Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger, The Mummy Returns, Krrish 3, Transformers: Revenge of the Fallen, Samsara and Kajraare.[101]

- Petra appeared in an episode of Time Scanners, made for National Geographic, where six ancient structures were laser scanned, with the results built into 3D models.[102] Examining the model of Petra revealed insights into how the structure was built.[103]

- Petra was the focus of an American PBS Nova special, "Petra: Lost City of Stone",[104] which premiered in the US and Europe in February 2015.

- Petra is central to Netflix's first Arabic original series Jinn, which is a young adult supernatural drama about the djinn in the ancient city of Petra. They must try and stop the demons from destroying the world. The show is shot in Jordan and has five episodes.[105]

- Six months after a deadly hike by two Israelis in 1958, Haim Hefer wrote the lyrics for a ballad called HaSela haAdom ("The Red Rock")[106]

- In 1977, the Lebanese Rahbani brothers wrote the musical Petra as a response to the Lebanese Civil War.[107]

Gallery

Siq, rays of light

Siq, rays of light.jpg.webp) The Obelisk Tomb

The Obelisk Tomb The Garden Temple

The Garden Temple The Colored Triclinium

The Colored Triclinium Rock graves

Rock graves Petra Monastery Trail

Petra Monastery Trail Temple of Dushares, Petra

Temple of Dushares, Petra

See also

- Hegra (Mada'in Salih) – Historical site in northwest Saudi Arabia

- Incense Route – Desert Cities in the Negev – UNESCO World Heritage Site in Negev, Israel

- List of colossal sculptures in situ

- List of modern names for biblical place names

- Ridge Church – Ruined church in Petra, Jordan

Notes

- "Management of Petra". Petra National Trust. Archived from the original on 19 April 2015. Retrieved 14 April 2015.

- Browning, Iain (1973, 1982), Petra, Chatto & Windus, London, p. 15, ISBN 0-7011-2622-1

- Stephan G. Schmid and Michel Mouton (2013). Men on the Rocks: The Formation of Nabataean Petra. Logos Verlag Berlin GmbH. ISBN 9783832533137. Archived from the original on 18 March 2020. Retrieved 14 November 2019.

- Shaddel, Mehdy (2017-10-01). "Studia Onomastica Coranica: AL-Raqīm, Caput Nabataeae*". Journal of Semitic Studies. 62 (2): 303–318. doi:10.1093/jss/fgx022. ISSN 0022-4480. Retrieved 2020-12-08.

- "Major Attractions: Petra". Jordan Tourism Board. Archived from the original on 2016-11-04.

- One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Cooke, George Albert (1911). "Petra". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 21 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 309–310.

- "A Short History". Petra National Foundation. Archived from the original on 4 December 2017. Retrieved 13 February 2014.

- Taylor, Jane (2001). Petra and the Lost Kingdom of the Nabataeans. London: I.B.Tauris. pp. 14, 17, 30, 31. ISBN 9781860645082. Archived from the original on 3 July 2019. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- Mati Milstein. "Petra. The "Lost City" still has secrets to reveal: Thousands of years ago, the now-abandoned city of Petra was thriving". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 20 December 2019. Retrieved 27 December 2019.

- Jack D. Elliott Jr. (1996). Joe D. Seger (ed.). The Nabatean Synthesis of Avraham Negev: A Critical Appraisal. p. 56. ISBN 9781575060125. Archived from the original on 14 June 2020. Retrieved 27 December 2019.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - "Petra Lost and Found". National Geographic. 2 January 2016. Archived from the original on 8 April 2018. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- "Petra lost and found". History Magazine. 2018-02-09. Retrieved 2021-01-15.

- Glueck, Grace (17 October 2003). "ART REVIEW; Rose-Red City Carved From the Rock". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 28 December 2017. Retrieved 29 January 2018.

- "UNESCO advisory body evaluation" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-01-13. Retrieved 2011-12-05.

- ""Lost City" of Petra Still Has Secrets to Reveal". Science. 2017-01-26. Retrieved 2021-01-15.

- "Rose-red city of Petra wraps up 2019 with record-breaking 1,135,300 visitors". The Jordan Times. 6 January 2020. Archived from the original on 5 January 2020. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- "Petra welcomed 905,000 visitors in 2022". The Jordan Times. 2 January 2023. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- Steven Grosby (2007). Nationalism and Ethnosymbolism: History, Culture and Ethnicity in the Formation of Nations. Edinburgh University Press. p. 109. ISBN 9780748629350. Retrieved 19 December 2017.

- "Why Were the Ancient Israelites and Edomites Enemies". dailyhistory.org. Retrieved 2021-12-03.

- "Petra | Bible Interp". bibleinterp.arizona.edu. Retrieved 2021-12-03.

- Bienkowski, P. (1992). "The beginning of the Iron Age in Edom: A reply to Finkelstein". Levant. 24 (1): 167–169. doi:10.1179/007589192790220919.

- Maalouf, Tony (2003). Arabs in the Shadow of Israel: The Unfolding of God's Prophetic Plan for Ishmael's Line. Kregel Academic. ISBN 9780825493638. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- Josephus (1930). Jewish Antiquities. doi:10.4159/DLCL.josephus-jewish_antiquities.1930. Archived from the original on 2018-12-26. Retrieved 2016-08-06 – via Loeb Classical Library.

- Hagith Sivan (2008). Palestine in Late Antiquity. Oxford University Press. p. 254.

- J. Starcky (1965). "Nouvelle épitaphe Nabatéenne donnant le nom Sémitique de Pétra". Revue Biblique. 72 (1): 95–97. JSTOR 44087833.

- J. Starcky (1965). "Nouvelles stelles funeraires a Petra" (PDF). Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan. 10: 43–29 & plates.

- Diodorus Siculus. "Section 95 (note 79)". Account of Antigonus' expedition to Arabia. Vol. xix. Archived from the original on 2020-05-27. Retrieved 2016-08-07.

- Dio Cassius, LXVII. 14, 5.

- Alpass, Peter (2013). "Chapter 2". The Religious Life of Nabataea.

- "Petra Jordan". jordantourspetra.com. 21 June 2019. Archived from the original on 2019-12-08. Retrieved 2019-11-22.

- Glueck, Grace (2003-10-17). "ART REVIEW; Rose-Red City Carved From the Rock". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2006-04-18. Retrieved 2010-05-22.

- Frösén, Jaakko (2012). "Petra papyri". The Encyclopedia of Ancient History. Blackwell Publishing Ltd. doi:10.1002/9781444338386.wbeah06244. ISBN 9781444338386.

- Zbigniew T. Fiema, Ahmad Al-Jallad, Michael C. A. Macdonald, and Laïla Nehmé, "Provincia Arabia: Nabataea, the Emergence of Arabic as a Written Language, and Graeco-Arabica, in Greg Fisher (ed.), Arabs and Empires before Islam (Oxford University Press, 2015), p. 394.

- "Nabataea: The Crusades". nabataea.net. Archived from the original on 2018-05-03. Retrieved 2018-12-25.

- Lawler, Andrew. "Reconstructing Petra". Smithsonian. Archived from the original on 2018-12-25. Retrieved 2018-12-25.

- Burckhardt, John Lewis (1822). Travels in Syria and the Holy Land. J. Murray.

- "The discovery of Petra | History Today". www.historytoday.com. Retrieved 2021-12-03.

- Carr, Gerald L. (1994). Frederic Edwin Church: Catalogue Raisonne of Works at Olana State Historic Site, Volume I. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 386–396. ISBN 978-0521385404.

- Conway, A.; Horsfield, G. (1930). "Historical and Topographical Notes on Edom: with an account of the first excavations at Petra". The Geographical Journal. 76 (5): 369–390. doi:10.2307/1784200. JSTOR 1784200.

- Forbidden Archaeology of Petra and Nazca. National Geographic. 2018. Archived from the original (documentary) on 2020-05-02. Retrieved 2020-02-12 – via YouTube.

- "Petra". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 2017-08-20. Retrieved 2017-08-20.

- "Tourists evacuated after floods lash Jordan's ancient city of Petra". ITV News. 2022-12-27. Retrieved 2022-12-27.

- "Petra: Water Works". Nabataea.net. Archived from the original on 2011-11-26. Retrieved 2011-12-05.

- Lisa Pinsker (2001-09-11). "Petra: An Eroding Ancient City". Agiweb.org. Archived from the original on 2012-03-31. Retrieved 2011-12-05.

- "Robert Fulford's column about Petra, Jordan". Robertfulford.com. 1997-06-18. Archived from the original on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2014-02-06.

- "Petra: Rock-cut façades (article)". Khan Academy. Retrieved 2021-12-03.

- "Alexandria". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2021-12-03.

- "Theatre | Jordan Attractions". Lonely Planet. Retrieved 2021-12-03.

- Bachmann, W., Watzinger, C. Wiegand, T. (1921). Petra, vol 3. Wissenschaftliche Vero¨ffentlichungen des Deutsch-Turkischen Denkmalschutz-Kommandos 3. Berlin: De Gruyter. pp. 37–41.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Bedal, L-A (2004). The Petra Pool-Complex: a Hellenistic Paradeisos in the Nabataean Capital. Piscataway (NJ): Gorgias Press.

- Bedal L-A, Gleason K. L., Schryver J. G. (2007). "The Petra Garden and Pool Complex, 2003–2005". Annu Dep Antiq Jordan. 51: 151–176.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Bedal L-A, Schryver J. G., Gleason K. L. (2011). "The Petra Garden and Pool Complex, 2007 and 2009 field seasons". Annu Dep Antiq Jordan. 55: 313–328.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "The Ancient City of Petra | AMNH".

- "The High Place of Sacrifice". Tourist Jordan. 2018-01-03. Retrieved 2021-12-03.

- "Petra". www.memphistours.com. Retrieved 2021-12-03.

- "Royal Tombs, Petra. Art Destination Jordan". universes.art. Retrieved 2021-12-03.

- Parcak, Sarah; Tuttle, Christopher A. (May 2016). "Hiding in Plain Sight: The Discovery of a New Monumental Structure at Petra, Jordan, Using WorldView-1 and WorldView-2 Satellite Imagery". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research. 375 (375): 35–51. doi:10.5615/bullamerschoorie.375.0035. ISSN 0003-097X. JSTOR 10.5615/bullamerschoorie.375.0035. S2CID 163171099.

- "Archaeologists discover massive Petra monument that could be 2,150 years old". The Guardian. 10 June 2016. Archived from the original on 10 June 2016. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- "Massive New Monument Found in Petra". National Geographic. 8 June 2016. Archived from the original on 9 June 2016. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- Paradise T.R. & Angel C.C. 2015, Nabatean Architecture and the Sun, ArcUser (Winter) Archived 2015-04-02 at the Wayback Machine.

- Negev 11

- Gibson, Dan (2017). Early Islamic Qiblas: A survey of mosques built between 1AH/622 C.E. and 263 AH/876 C.E. Independent Scholars Press. ISBN 978-1927581223.

- King, David A. The Petra Fallacy. Archived from the original on 2020-12-08. Retrieved 2019-09-15.

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- "Petra". Sacred Sites. Archived from the original on 2010-08-21. Retrieved 2011-12-05.

- "Map of the area". go2petra.com. Archived from the original on 2018-03-13. Retrieved 2015-06-04.

- "Archeological Park". VisitPetra.jo. Archived from the original on 2018-09-02. Retrieved 2018-12-25.

- "The Cultural Space of the Bedu in Petra and Wadi Rum". UNESCO Culture Sector. Archived from the original on 2015-11-05. Retrieved 2015-06-02.

- "Strategic Plan for Umm Sayhoun and surrounding areas" (PDF). pdtra.gov.jo. Petra Development and Tourism Region Authority in Association with DesignWorkshop and JCP s.r.l. Retrieved 8 April 2017.

- Heinrichs, K.; Azzam, R. (June 2012). "Investigation of salt weathering on stone monuments by use of a modern wireless sensor network exemplified for the rock-cut monuments in Petra / Jordan – a research project". International Journal of Heritage in the Digital Era. 1 (2): 191–216. doi:10.1260/2047-4970.1.2.191.

- "Heritage at Risk 2004/2005: Petra" (PDF). icomos.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 March 2016. Retrieved 27 March 2017.

- "Heritage Conservation Grips Jordan's Petra Amid Booming Tourism". Xinhua News Agency. November 3, 2007. Archived from the original on September 18, 2009.

- "Petra National Trust-About". petranationaltrust.org. Archived from the original on 2011-12-28. Retrieved 2011-12-05.

- Comer, Douglas C.; Willems, Willem J. H. "Tourism and Archaeological Heritage Management at Petra: Driver to Development or Destruction?" (PDF). icomos.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2015-09-10.

- Usher, Sebastian (January 16, 2018). "Jordan urged to end animal mistreatment at Petra site". BBC News. Archived from the original on February 13, 2018. Retrieved February 28, 2018.

- Rawashdeh, Saeb (5 April 2018). "Stakeholders take steps to address animal abuse in Petra". The Jordan Times. Archived from the original on 19 April 2018. Retrieved 19 April 2018.

- "PETA says 'donkeys need to be banned' after new video reveals animals being abused at Petra site in Jordan," Yahoo.com, 8 February 2020.

- "PETA veterinary clinic in Petra is the only facility in the area providing free emergency medical care to injured and neglected donkeys, horses, and other animals used to give tourist rides, 197Lines.com, 4 May 2021."

- Petra : Begleitbuch zur Ausstellung "PETRA — Wunder in der Wüste : Auf den Spuren von J.L. Burckhardt alias Scheich Ibrahim" : Eine Ausstellung des Antikenmuseums Basel und Sammlung Ludwig in Zusammenarbeit mit dem Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities/Department of Antiquities of Jordan und dem Jordan Museum, Amman, Antikenmuseum Basel und Sammlung Ludwig, 23. Oktober 2012 bis 17. März 2013 = Batrāʼ. Meijden, Ella van der., Schmid, Stephan G., Voegelin, Andreas F., Antikenmuseum Basel., Museum Ludwig. Basel: Schwabe. 2012. pp. 15–17. ISBN 978-3-7965-2849-1. OCLC 818416033. Archived from the original on 2020-12-08. Retrieved 2020-12-08.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Meijden, Ella van der (2012). "Reisende und Gelehrte. Die frühe Petra-Forschung nach J. L. Burckhardt". Petra : Begleitbuch zur Ausstellung "PETRA — Wunder in der Wüste : Auf den Spuren von J.L. Burckhardt alias Scheich Ibrahim" : Eine Ausstellung des Antikenmuseums Basel und Sammlung Ludwig in Zusammenarbeit mit dem Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities/Department of Antiquities of Jordan und dem Jordan Museum, Amman, Antikenmuseum Basel und Sammlung Ludwig, 23. Oktober 2012 bis 17. März 2013 = Batrāʼ. Meijden, Ella van der., Schmid, Stephan G., Voegelin, Andreas F., Antikenmuseum Basel., Museum Ludwig. Basel: Schwabe. pp. 39–40. ISBN 978-3-7965-2849-1. OCLC 818416033. Archived from the original on 2020-12-08. Retrieved 2020-12-08.

- Meijden, Ella van der (2012). "Reisende und Gelehrte. Die frühe Petra-Forschung nach J. L. Burckhardt". Petra : Begleitbuch zur Ausstellung "PETRA — Wunder in der Wüste : Auf den Spuren von J.L. Burckhardt alias Scheich Ibrahim" : Eine Ausstellung des Antikenmuseums Basel und Sammlung Ludwig in Zusammenarbeit mit dem Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities/Department of Antiquities of Jordan und dem Jordan Museum, Amman, Antikenmuseum Basel und Sammlung Ludwig, 23. Oktober 2012 bis 17. März 2013 = Batrāʼ. Meijden, Ella van der., Schmid, Stephan G., Voegelin, Andreas F., Antikenmuseum Basel., Museum Ludwig. Basel: Schwabe. p. 41. ISBN 978-3-7965-2849-1. OCLC 818416033. Archived from the original on 2020-12-08. Retrieved 2020-12-08.

- "Visit Petra". 8 December 2020. Archived from the original on 8 February 2020.

- "Culture in Crisis: Flows of Peoples, Artifacts and Ideas, ICHAJ 14" (PDF). CAMNES- Center for Ancient Mediterranean and Near Eastern Studies. 8 December 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 December 2020.

- Wedekind, Wanja (2005). "Preventive Conservation for the Protection of the sandstone Facades in Petra/Jordan". Bulletin -- Journal of Conservation-Restoration. 16 (1 (60)): 48–53.

- Kühlenthal, Michael. (2000). Petra : die Restaurierung der Grabfassaden = The restoration of the rockcut tomb facades. Fischer, Helge., Germany. Bundesministerium für Wirtschaftliche Zusammenarbeit und Entwicklung. München: Bayerischen Landesamt für Denkmalpflege. ISBN 3-87490-707-4. OCLC 44937402. Archived from the original on 2020-12-08. Retrieved 2020-12-08.

- Bala‟awi, Fadi; Waheeb, Mohammed; Alshawabkeh, Yahya; Alawneh, Firas. "Conservation work at Petra: What had been done and what is needed" (PDF). Queen Rania's Institute of Tourism and Heritage Hashemite University. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 February 2013. Retrieved 8 December 2020.

- Zayadine, F., 1981, Recent Excavation & Restoration of the department of Antiquties (1979- 1980), ADAJ (Annual of the Department of Antiquities, Amman- Jordan), Vol. 24. pp: 341-355

- Zayadine, F. (1986). "Recent Excavation & Restoration at Qasr El Bint of Petra". ADAJ (Annual of the Department of Antiquities, Amman- Jordan). 29: 239–249.

- Joukowsky, M. (1999). "The Brown University 1998 Excavations at The Petra Great Temple". ADAJ (Annual of the Department of Antiquities, Amman- Jordan). 43: 195–222.

- "Petra National Trust". 11 December 2020. Archived from the original on 7 March 2021. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- W. Wedekind, H. Fischer: Salt weathering and the evaluation of desalination and restoration in Petra/Jordan. In: Laue, S. (Hrsg.) SWBSS 2017 4th International Conference on Salt Weathering of Buildings and Stone Sculptures, 20–22 September 2017 – Potsdam, Potsdam 2017, pp: 190–299.

- "CICS – Petra Painting Conservation Project – Workshop 2019 – TH Köln". www.th-koeln.de. Archived from the original on 2020-12-08. Retrieved 2020-12-08.

- "DFG – GEPRIS – Characterisation and Conservation of Paintings on Walls and Sculpture from Nabataean Petra". gepris.dfg.de. Archived from the original on 2020-12-08. Retrieved 2020-12-08.

- Balliett, Blue (2004). Chasing Vermeer: Afterwords by Leslie Budnick: Author Q&A. Scholastic. ISBN 978-0-439-37294-7.

- Geldermalsen, Marguerite (2010). Married to a Bedouin. Virago UK. ISBN 978-1844082209. Archived from the original on 2013-10-29. Retrieved 2013-10-25.

- Ward, Joan (2014). Living With Arabs: Nine Years with the Petra Bedouin. UM Peter Publishing. ISBN 978-1502564917.

- "John Yarbrough's Petra on Youtube". YouTube. Archived from the original on 2016-11-29. Retrieved 2015-05-05.

- "Manhattan Repertory Theatre fall one act competition 2014 including John Yarbrough's Petra". Archived from the original on 2015-05-18. Retrieved 2015-06-04.

- "Broadwayworld, Off-Off-Broadway, article: 'Playwright John Yarbrough Wins Strawberry One Act Festival'". Archived from the original on 2015-05-05. Retrieved 2015-06-04.

- "Broadwayworld, Off-Off-Broadway, article: 'The Best American Short Plays 2014-15 Hits the Shelves'". Archived from the original on 2016-08-22. Retrieved 2016-08-10.

- Mourby, Adrian (16 September 2016). "Can Jordan's 'Indiana Jones' city survive?". CNN Travel. Archived from the original on 17 April 2019. Retrieved 17 April 2019.

- "Time Scanners". Archived from the original on September 28, 2015.

- "Time Scanners: How was Petra built?". BBC Focus Magazine. Archived from the original on 2019-01-06. Retrieved 2019-01-05.

- "Petra-Lost City in building-wonders at pbs.org". PBS. 11 February 2015. Archived from the original on 2017-08-28. Retrieved 2017-09-08.

- "Netflix's first Arabic original series sparks uproar in Jordan". www.aljazeera.com. Archived from the original on 2020-02-19. Retrieved 2020-02-19.

- Dominik Peters (2015). "Melody of a Myth: The Legacy of Haim Hefers Red Rock Song" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-09-25. Retrieved 2019-09-23.

- "The Ballad of Red Rock". The New York Times. January 17, 1971. Archived from the original on 2019-09-23. Retrieved September 23, 2019. - Stone, Christopher. Popular Culture and Nationalism in Lebanon.

Bibliography

- Bedal, Leigh-Ann (2004). The Petra Pool-Complex: A Hellenistic Paradeisos in the Nabataean Capital. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press. ISBN 978-1-59333-120-7.

- Brown University. "The Petra Great Temple; History" Accessed April 19, 2013.

- Glueck, Nelson (1959). Rivers in the Desert: A History of the Negev. New York: Farrar, Straus & Cudahy/London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson

- Harty, Rosemary. "The Bedouin Tribes of Petra Photographs: 1986–2003". Retrieved 2008-07-17.

- Hill, John E. (2004). The Peoples of the West from the Weilue 魏略 by Yu Huan 魚豢 : A Third Century Chinese Account Composed between 239 and 265 CE.

Draft annotated English translation where Petra is referred to as the Kingdom of Sifu.

- McKenzie, Judith (1990). The Architecture of Petra. (Oxford University Press)

- Mouton, Michael and Schmid, Stephen G. (2013) "Men on the Rocks: The Formation of Nabataean Petra"

- Paradise, T. R. (2011). "Architecture and Deterioration in Petra: Issues, trends and warnings" in Archaeological Heritage at Petra: Drive to Development or Destruction?" (Doug Comer, editor), ICOMOS-ICAHM Publications through Springer-Verlag NYC: 87–119.

- Paradise, T. R. (2005). "Weathering of sandstone architecture in Petra, Jordan: influences and rates" in GSA Special Paper 390: Stone Decay in the Architectural Environment: 39–49.

- Paradise, T. R. and Angel, C. C. (2015). Nabataean Architecture and the Sun: A landmark discovery using GIS in Petra, Jordan. ArcUser Journal, Winter 2015: 16-19pp.

- Reid, Sara Karz (2006). The Small Temple. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press. ISBN 978-1-59333-339-3.

Reid explores the nature of the small temple at Petra and concludes it is from the Roman era.

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre. "Petra" Accessed April 19, 2013.

- "The Zamani Project, Petra, Jordan (مشروع زماني، البترا) - MaDiH (مديح)". maDIH. Archived from the original on 2020-07-12. Retrieved 2020-07-09.

External links

- University of Arkansas Petra Project. Retrieved 27 March 2017

- Open Context, "Petra Great Temple Excavations (Archaeological Data)", Open Context publication of archaeological data from the 1993–2006

- Petra History and Photo Gallery, history with maps. Retrieved 27 March 2017

- Parker, S., R. Talbert, T. Elliott, S. Gillies, S. Gillies, J. Becker. "Places: 697725 (Petra)", Pleiades. Retrieved 27 March 2017

- Jordanian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities

- Special Issue on Petra and Nabatean Culture, Jordan Journal for History and Archaeology, 2020

- Photos of Petra at the American Center of Research

.jpg.webp)