Peter Warlock

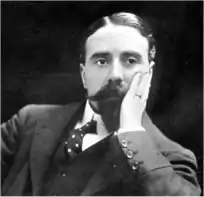

Philip Arnold Heseltine (30 October 1894 – 17 December 1930), known by the pseudonym Peter Warlock, was a British composer and music critic. The Warlock name, which reflects Heseltine's interest in occult practices, was used for all his published musical works. He is best known as a composer of songs and other vocal music; he also achieved notoriety in his lifetime through his unconventional and often scandalous lifestyle.

As a schoolboy at Eton College, Heseltine met the British composer Frederick Delius, with whom he formed a close friendship. After a failed student career in Oxford and London, Heseltine turned to musical journalism, while developing interests in folk-song and Elizabethan music. His first serious compositions date from around 1915. Following a period of inactivity, a positive and lasting influence on his work arose from his meeting in 1916 with the Dutch composer Bernard van Dieren; he also gained creative impetus from a year spent in Ireland, studying Celtic culture and language. On his return to England in 1918, Heseltine began composing songs in a distinctive, original style, while building a reputation as a combative and controversial music critic. During 1920–21 he edited the music magazine The Sackbut. His most prolific period as a composer came in the 1920s, when he was based first in Wales and later at Eynsford in Kent.

Through his critical writings, published under his own name, Heseltine made a pioneering contribution to the scholarship of early music. In addition, he produced a full-length biography of Delius and wrote, edited, or otherwise assisted the production of several other books and pamphlets. Towards the end of his life, Heseltine became depressed by a loss of his creative inspiration. He died in his London flat of coal gas poisoning in 1930, probably by suicide.

Life

Childhood and family background

Heseltine was born on 30 October 1894 at the Savoy Hotel, London, which his parents were using at the time as their town residence.[1] The family was wealthy, with strong artistic connections and some background in classical scholarship.[2] Philip's parents were Arnold Heseltine, a solicitor in the family firm, and Bessie Mary Edith, née Covernton. She was the daughter of a country doctor from the Welsh border town of Knighton and was Arnold's second wife. Soon after Philip's birth, the family moved to Chelsea where he attended a nearby kindergarten and received his first piano lessons.[3]

In March 1897 Arnold Heseltine died suddenly at the age of 45. Six years later, Bessie married a Welsh landowner and local magistrate, Walter Buckley Jones, and moved to Jones's estate, Cefn Bryntalch, Llandyssil, near Montgomery, although the London house was retained.[4][5] The youthful Philip was proud of his Welsh heritage and retained a lifelong interest in Celtic culture; later he would live in Wales during one of his most productive and creative phases.[6]

In 1903 Heseltine entered Stone House Preparatory School in Broadstairs, where he showed precocious academic ability and won several prizes.[4][7] In January 1908, at a concert in the Royal Albert Hall, he heard a performance of Lebenstanz, composed by Frederick Delius. The work made little impression on him until he discovered that his uncle, Arthur Joseph Heseltine (known as "Joe"), an artist, lived close to Delius's home in Grez-sur-Loing in France. Philip then used the connection to obtain the composer's autograph for Stone House's music teacher, W. E. Brockway.[8]

Eton: first meeting with Delius

.jpg.webp)

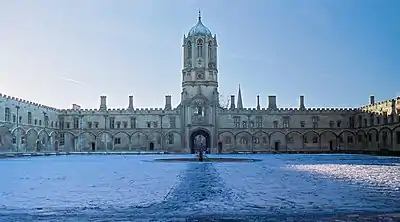

Heseltine left Stone House in the summer of 1908 and began at Eton College that autumn. His biographer Ian Parrott records that he loathed Eton, "with its hearty adolescent bawling of Victorian hymns in an all-male college chapel". He was equally unhappy with other aspects of school life, such as the Officers' Training Corps, the suggestive homosexuality, and endemic bullying.[9] He found relief in music and, perhaps because of the connection with his uncle, formed an interest in Delius that developed into a near-obsession. He also found a kindred spirit in an Eton music teacher and Delius advocate, the cellist Edward Mason, from whom Heseltine borrowed a copy of the score of Sea Drift. He thought it "heavenly", and was soon requesting funds from his mother to purchase more of Delius's music.[8] According to Cecil Gray, Heseltine's first biographer, "[Heseltine] did not rest until he had procured every work of Delius which was then accessible".[10]

In June 1911 Heseltine learned that Thomas Beecham was to conduct an all-Delius concert at London's Queen's Hall on the 16th of that month, at which the composer would be present, and his Songs of Sunset would be given its first performance. Colin Taylor, a sympathetic Eton piano tutor, secured permission from the school for Heseltine to attend the event. Prior to this, his mother had contrived to meet Delius in her London home; as a consequence, during the concert intermission Heseltine was introduced to the composer. The next day he wrote Delius a long appreciative letter: "I cannot adequately express in words the intense pleasure it was to me to hear such perfect performances of such perfect music".[11] He told his mother that "Friday evening was the most perfectly happy evening I have ever spent, and I shall never forget it".[12] Delius became the first strong formative influence of Heseltine's compositional career, and although the initial adulation was later modified, a friendship began that would largely endure for the remainder of Heseltine's life.[4][13]

Cologne, Oxford and London

By the summer of 1911, a year before he was due to leave the school, Heseltine had tired of life at Eton. Without a clear plan for his future, he asked his mother if he could live abroad for a while. His mother wanted him to go to university, and then either into the City or the Civil Service, but she agreed to his request with the proviso that he would resume his education later. In October 1911 he proceeded to Cologne to learn German and to study piano at the conservatory.[14] In Cologne Heseltine produced his first few songs which, like all his earliest works, were highly imitative of Delius.[15] The piano studies went poorly, although Heseltine expanded his musical experiences by attending concerts and operas. He also experimented with general journalism, publishing an article in Railway and Travel Monthly on the subject of a disused Welsh branch line.[16]

In March 1912 Heseltine returned to London and engaged a tutor to prepare for his university entrance examinations. He spent time with Delius at that summer's Birmingham Festival,[17] and published his first music criticism, an article on Arnold Schoenberg that appeared in the Musical Standard in September 1912.[18] Despite his mother's wishes and his lack of formal musical training, he hoped to make a career in music. He consulted Delius, who advised him that, if his mind was set, he should follow his instincts and pursue this objective in the face of all other considerations.[19] Beecham, who knew both men, later sharply criticised this advice, on the grounds of Heseltine's immaturity and instability. "Frederick should never have committed the psychological blunder of preaching the doctrine of relentless determination to someone incapable of receiving it".[20] In the end Heseltine acceded to his mother's wishes. After passing the necessary examinations, he was accepted to study classics at Christ Church, Oxford, and began there in October 1913.[21]

A female acquaintance at Christ Church described the 19-year-old Heseltine as "probably about 22, but he appears to be years older ... 6 feet high, absolutely fit ... brilliant blue eyes ... and the curved lips and highhead carriage of a young Greek God".[22] Although he enjoyed social success, he soon became depressed and unhappy with Oxford life. In April 1914 he spent part of his Easter vacation with Delius at Grez, and worked with the composer on the scores of An Arabesque and Fennimore and Gerda, in the latter case providing an English version of the libretto.[23][24] He did not return to Oxford after the 1914 summer vacation; with his mother's reluctant consent he moved to Bloomsbury in London, and enrolled at University College London to study language, literature and philosophy.[25] In his spare time he conducted a small amateur orchestra in Windsor, after admitting to Delius that he knew nothing of the art of conducting.[26] However, his life as a student in London was brief; in February 1915, with the help of Lady Emerald Cunard (a mistress of Beecham) he secured a job as a music critic for the Daily Mail at a salary of £100 per year. He promptly abandoned his university studies to begin this new career.[25]

Music critic

During Heseltine's four months at the Daily Mail, he wrote about 30 notices, mainly short reports of musical events but occasionally with some analysis.[25] His first contribution, dated 9 February 1915, described a performance by Benno Moiseiwitsch of Delius's Piano Concerto in C minor, as "masterly", while Delius was hailed as "the greatest composer England has produced for two centuries". The other work in the programme was "the last great symphony that has been delivered to the world": the Symphony in D minor by Franck.[27] He wrote for other publications; a 5000-word article, "Some notes on Delius and his Music", appeared in the March 1915 issue of The Musical Times,[25][28] in which Heseltine opined: "There can be no superficial view of Delius's music: either one feels it in the very depths of one's being, or not at all". Only Beecham, Heseltine suggested, was capable of interpreting the music adequately.[29] Heseltine's last notice for the Daily Mail was dated 17 June;[30] later that month he resigned, frustrated by the paper's frequent cutting of his more critical opinions.[31] Unemployed, he spent his days in the British Museum, studying and editing Elizabethan music.[13]

New friends and acquaintances

Heseltine spent much of the 1915 summer in a rented holiday cottage in the Vale of Evesham, with a party that included a young artist's model named Minnie Lucie Channing, who was known as "Puma" because of her volatile temperament. She and Heseltine soon entered into a passionate love affair.[32] During this summer break Heseltine shocked neighbours by his uninhibited behaviour, which included riding a motorcycle naked down nearby Crickley Hill.[33][n 1] However, his letters show that at this time he was often depressed and insecure, lacking any clear sense of purpose.[4] In November 1915 his life gained some impetus when he met D. H. Lawrence and the pair found an immediate rapport. Heseltine declared Lawrence to be "the greatest literary genius of his generation",[35] and enthusiastically fell in with the writer's plans to found a Utopian colony in America. In late December he followed the Lawrences to Cornwall, where he tried, unavailingly, to set up a publishing company with them.[13] Passions between Heseltine and Puma had meanwhile cooled; when she revealed that she was pregnant, Heseltine confided to Delius that he had little liking for her and had no intention of helping her to raise this unwanted child.[36]

In February 1916 Heseltine returned to London, ostensibly to argue for exemption from military service. However, it became clear that there had been a rift with Lawrence; in a letter to his friend Robert Nichols, Heseltine described Lawrence as "a bloody bore determined to make me wholly his and as boring as he is".[37] The social centre of Heseltine's life now became the Café Royal in Regent Street, where among others he met Cecil Gray, a young Scottish composer. The two decided to share a Battersea studio, where they planned various unfulfilled schemes, including a new music magazine,[38] and, more ambitiously, a London season of operas and concerts. Heseltine declined an offer from Beecham to participate in the latter's English Opera Company, writing to Delius that Beecham's productions and choices of works were increasingly poor and lacking in artistic value; in his own venture there would be "no compromise with the mob".[39] Beecham ridiculed the plan; he said it would "be launched and controlled by persons without the smallest experience of theatrical life".[40]

An event of considerable significance in Heseltine's musical life, late in 1916, was his introduction to the Dutch composer Bernard van Dieren. This friendship considerably influenced Heseltine, who for the rest of his life continued to promote the older composer's music.[41] In November 1916 Heseltine used the pseudonym "Peter Warlock" for the first time, in an article on Eugene Aynsley Goossens' chamber music for The Music Student.[42][43][n 2]

Puma bore a son in July 1916, though there is confusion about the child's exact identity. Most biographers assumed him to be Nigel Heseltine, the future writer who published a memoir of his father in 1992. However, in that memoir Nigel denied that Puma was his mother; he was, he says, the result of a concurrent liaison between Heseltine and an unnamed Swiss girl. Subsequently, he was given to foster-parents, then adopted by Heseltine's mother.[44] Parrott records that the son born to Puma was called Peter, and died in infancy.[45] Smith, however, states that Puma's baby was originally called Peter but was renamed Nigel "for reasons which have not as yet been satisfactorily explained". Whatever the truth of the paternity, and in spite of their mutual misgivings, Heseltine and Puma were married at Chelsea Register Office on 22 December 1916.[46]

Ireland

By April 1917 Heseltine had again tired of London life. He returned to Cornwall where he rented a small cottage near the Lawrences, and made a partial peace with the writer. By the summer of 1917, as Allied fortunes in the war stagnated, Heseltine's military exemption came under review; to forestall a possible conscription, in August 1917 he moved to Ireland, taking Puma, with whom he had decided he was, after all, in love.[47]

In Ireland Heseltine combined studies of early music with a fascination for Celtic languages, withdrawing for a two-month period to a remote island where Irish was spoken exclusively.[48] Another preoccupation was an increasing fascination with magical and occult practices, an interest first awakened during his Oxford year and revived in Cornwall.[13] A letter to Robert Nichols indicates that at this time he was "tamper[ing] ... with the science vulgarly known as Black Magic". To his former tutor Colin Taylor, Heseltine enthused about books "full of the most astounding wisdom and illumination"; these works included Eliphas Levi's History of Transcendental Magic, which includes procedures for the invocation of demons.[49] These diversions did not prevent Heseltine from participating in Dublin's cultural life. He met W. B. Yeats, a fellow-enthusiast for the occult, and briefly considered writing an opera based on the 9th-century Celtic folk-tale of Liadain and Curithir.[50] The composer Denis ApIvor has indicated that Heseltine's obsession with the occult was eventually replaced by his studies in religious philosophies, to which he was drawn through membership of a theosophist group in Dublin. Heseltine's interest in this field had originally been aroused by Kaikhosru Sorabji, the composer who had introduced him to the music of Béla Bartók.[51]

On 12 May 1918 Heseltine delivered a well-received illustrated lecture, "What Music Is", at Dublin's Abbey Theatre, which included musical excerpts from Bartók, the French composer Paul Ladmirault, and Van Dieren.[52][53] Heseltine's championing of Van Dieren's music led in August 1918 to a vituperative war of words with the music publisher Winthrop Rogers, over the latter's rejection of several Van Dieren compositions. This dispute stimulated Heseltine's own creative powers, and in his final two weeks in Ireland he wrote ten songs, which later critics have considered to be among his finest work.[4][54]

Journalism and The Sackbut

When Heseltine returned to London at the end of August 1918 he sent seven of his new songs to Rogers for publication. Because of the recent contretemps over Van Dieren, Heseltine submitted these pieces as "Peter Warlock". They were published under this pseudonym, which he thereafter adopted for all his subsequent musical output, reserving his own name for critical and analytical writings.[4][13] At around this time the composer Charles Wilfred Orr recalled Heseltine as "a tall fair youth of about my own age", trying without success to convince a sceptical Delius of the merits of Van Dieren's piano works. Orr was particularly struck by Heseltine's whistling abilities which he describes as "flute-like in quality and purity".[55]

For the next few years Heseltine devoted most of his energy to musical criticism and journalism. In May 1919 he delivered a paper to the Musical Association, "The Modern Spirit in Music", that impressed E.J. Dent, the future Cambridge University music professor. However, much of his writing was confrontational and quarrelsome. He made dismissive comments about the current standards of musical criticism ("the average newspaper critic of music ... is either a shipwrecked or worn-out musician, or else a journalist too incompetent for ordinary reporting") which offended senior critics such as Ernest Newman. He wrote provocative articles in the Musical Times, and in July 1919 feuded with the composer-critic Leigh Henry over the music of Igor Stravinsky.[56]

In a letter dated 17 July 1919, Delius advised the younger man to concentrate either on writing or composing: "I ... know how gifted you are and what possibilities are in you".[57] By this time Heseltine's privately expressed opinions on Delius's music were increasingly critical, although in public he continued to sing his former mentor's praises.[58] In The Musical Times he cited Fennimore and Gerda, Delius's final opera, as "one of the most successful experiments in a new direction that the operatic stage has yet seen".[59]

Heseltine had long nurtured a scheme to launch a music magazine, which he intended to start as soon as he found appropriate backing. In April 1920, Rogers decided to replace his semi-moribund magazine The Organist and Choirmaster, with a new music journal, The Sackbut, and invited Heseltine to edit it.[13] Heseltine presided over nine issues, adopting a style that was combative and often controversial.[60][61] The Sackbut also organised concerts, presenting works by Van Dieren, Sorabji, Ladmirault and others.[62][63] However, Rogers withdrew his financial backing after five issues. Heseltine then struggled to run it himself for several months; in September 1921 the magazine was taken over by the publisher John Curwen, who promptly replaced Heseltine as editor with Ursula Greville.[64]

Productive years in Wales

With no regular income, in the autumn of 1921 Heseltine returned to Cefn Bryntalch, which became his base for the next three years. He found the atmosphere there conducive to creative efforts; he told Gray that "Wild Wales holds an enchantment for me stronger than wine or woman".[65] The Welsh years were marked by intense creative compositional and literary activity; some of Heseltine's best-known music, including the song-cycles Lilligay and The Curlew, were completed along with numerous songs, choral settings, and a string serenade composed to honour Delius's 60th birthday in 1922. Heseltine also edited and transcribed a large amount of early English music.[66][67] His recognition as an emerging composer was marked by the selection of The Curlew as representing contemporary British music at the 1924 Salzburg Festival.[68]

Heseltine's major literary work of this period was a biography of Delius, the first full-length study of the composer, which remained the standard work for many years.[69] On its 1952 reissue, the book was described by music publisher Hubert J. Foss as "a work of art, a charming and penetrating study of a musical poet's mind".[70] Heseltine also worked with Gray on a study of the 16th-century Italian composer Carlo Gesualdo, although disputes between the two men delayed the book's publication until 1926.[71]

While visiting Budapest in April 1921, Heseltine befriended the then little-known Hungarian composer and pianist Béla Bartók. When Bartók visited Wales in March 1922 to perform in a concert, he stayed for a few days at Cefn Bryntalch. Although Heseltine continued to promote Bartók's music, there are no records of further meetings after the Wales visit.[72] Heseltine's on-off friendship with Lawrence finally died, after a thinly disguised and unflattering depiction of Heseltine and Puma ("Halliday" and "Pussum") appeared in Women in Love, published in 1922. Heseltine began legal proceedings for defamation, eventually settling out of court with the publishers, Secker and Warburg.[73] Puma, meanwhile, had disappeared from Heseltine's life. She returned from Ireland before he did, and had lived for a while with the young child Nigel at Cefn Bryntalch where the local gentry considered her "not of the same order of society as we are".[74][75] There was no resumption of married life, and she left Heseltine sometime in 1922.[4]

In September and October 1923 Heseltine accompanied his fellow-composer Ernest John Moeran on a tour of eastern England, in search of original folk music. Later that year he and Gray visited Delius at Grez.[76] In June 1924 Heseltine left Cefn Bryntalch and lived briefly in a Chelsea flat, a stay marked by wild parties and considerable damage to the property. After spending Christmas 1924 in Majorca he leased a cottage (formerly occupied by Foss) in the Kent village of Eynsford.[71]

Eynsford

At Eynsford, with Moeran as his co-tenant, Heseltine presided over a bohemian household with a flexible population of artists, musicians and friends. Moeran had studied at the Royal College of Music before and after the First World War; he avidly collected folk music and had admired Delius during his youth.[77] Although they had much in common, he and Heseltine rarely worked together, though they did co-write a song, "Maltworms".[78] The other permanent Eynsford residents were Barbara Peache, Heseltine's long-term girlfriend whom he had known since the early 1920s, and Hal Collins, a New Zealand Māori who acted as a general factotum.[79] Peache was described by Delius's assistant Eric Fenby as "a very quiet, attractive girl, quite different from Phil's usual types".[79] Although not formally trained, Collins was a gifted graphic designer and occasional composer, who sometimes assisted Heseltine.[80] The household was augmented at various times by the composers William Walton[51] and Constant Lambert, the artist Nina Hamnett, and sundry acquaintances of both sexes.[81]

The ambience at Eynsford was one of alcohol (the "Five Bells" public house was conveniently across the road) and uninhibited sexual activity. These years are the primary basis for the Warlock legends of wild living and debauchery.[4] Visitors to the house left accounts of orgies, all-night drunken parties, and rough horseplay that at least once brought police intervention.[82] However, such activities were mainly confined to weekends; within this unconventional setting Heseltine accomplished much work, including settings from the Jacobean dramatist John Webster and the modern poet Hilaire Belloc, and the Capriol Suite in versions for string and full orchestra.[13][66] Heseltine continued to transcribe early music, wrote articles and criticism, and finished the book on Gesualdo. He attempted to restore the reputation of a neglected Elizabethan composer, Thomas Whythorne, with a long pamphlet which, years later, brought significant amendments to Whythorne's entry in The History of Music in England. He also wrote a general study of Elizabethan music, The English Ayre.[83]

In January 1927, Heseltine's string serenade was recorded for the National Gramophonic Society, by John Barbirolli and an improvised chamber orchestra. A year later, HMV recorded the ballad "Captain Stratton's Fancy", sung by Peter Dawson. These two are the only recordings of Heseltine's music released during his lifetime.[84] His association with the poet and journalist Bruce Blunt led to the popular Christmas anthem "Bethlehem Down", which the pair wrote in 1927 to raise money for their Christmas drinking.[85] By the summer of 1928 his general lifestyle had created severe financial problems, despite his industry. In October he was forced to give up the cottage at Eynsford, and returned to Cefn Bryntalch.[86]

Final years

By November 1928, Heseltine had tired of Cefn Bryntalch, and returned to London. He sought concert reviewing and cataloguing assignments without much success; his main creative activity was the editing, under the pseudonym "Rab Noolas" ("Saloon Bar" backwards), of Merry-Go-Down, an anthology in praise of drinking. The book, published by The Mandrake Press, was copiously illustrated by Hal Collins.[87]

Early in 1929 Heseltine received two offers from Beecham which temporarily restored his sense of purpose. Beecham had founded the Imperial League of Opera (ILO) in 1927; he now invited Heseltine to edit the ILO journal.[13][88] Beecham also asked Heseltine to help organise a festival to honour Delius, which the conductor was planning for October 1929.[89] Although Heseltine's enthusiasm for Delius's music had diminished, he accepted the assignment, and travelled to Grez in search of forgotten compositions that could be resurrected for the festival.[90] He declared that he was delighted to discover Cynara, for voice and orchestra, abandoned since 1907.[91] For the festival, Heseltine prepared many of the programme notes for individual concerts and supplied a concise biography of the composer.[92] According to Delius's wife Jelka: "Next to Beecham, he [Heseltine] really was the soul of the thing".[93]

At a Promenade Concert in August 1929, Heseltine conducted a performance of the Capriol Suite, the single public conducting engagement of his life.[94] In an effort to reproduce their success with "Bethlehem Down", he and Blunt proffered a new carol for Christmas 1929, "The Frostbound Wood". Although the work was technically accomplished, it failed to achieve the popularity of its predecessor.[95] Heseltine edited three issues of the ILO journal, but in January 1930, Beecham announced the closure of the venture, and Heseltine was out of work again.[96] His attempt on behalf of Van Dieren to raise financing to mount a performance of the latter's opera The Tailor also failed.[97]

The final summer of Heseltine's life was marked by gloom, depression, and inactivity; ApIvor refers to Heseltine's sense of "crimes against the spirit", and an obsession with imminent death.[98] In July 1930 a fortnight spent with Blunt in Hampshire brought a brief creative revival; Heseltine composed "The Fox" to Blunt's lyrics, and on his return to London he wrote "The Fairest May" for voice and string quartet. These were his final original compositions.[99][100]

Death

In September 1930 Heseltine moved with Barbara Peache into a basement flat at 12a Tite Street in Chelsea. With no fresh creative inspiration, he worked in the British Museum to transcribe the music of English composer Cipriani Potter, and made a solo version of "Bethlehem Down" with organ accompaniment. On the evening of 16 December Heseltine met Van Dieren and his wife for a drink and invited them home afterwards. According to Van Dieren, the visitors left at about 12:15 a.m. Neighbours later reported sounds of movement and of a piano in the early morning. When Peache, who had been away, returned early on 17 December, she found the doors and windows bolted, and smelled coal gas. The police broke into the flat and found Heseltine unconscious; he was declared dead shortly afterwards, apparently as the result of coal gas poisoning.[101][102]

An inquest was held on 22 December; the jury could not determine whether the death was accidental or suicide and an open verdict was returned.[103] Most commentators have considered suicide the more likely cause; Heseltine's close friend Lionel Jellinek and Peache both recalled that he had previously threatened to take his life by gas and the outline of a new will was found among the papers in the flat.[104] Much later, Nigel Heseltine introduced a new theory—that his father had been murdered by Van Dieren, the sole beneficiary of Heseltine's 1920 will, which stood to be revoked by the new one. This theory is not considered tenable by most commentators.[105][106] The suicide theory is supported (arguably), by the (supposed, accepted) fact that Heseltine/Warlock had put his young cat outside the room before he had turned on the lethal gas.[107]

Philip Heseltine was buried alongside his father at Godalming cemetery on 20 December 1930.[4] In late February 1931, a memorial concert of his music was held at the Wigmore Hall; a second such concert took place in the following December.[108]

In 2011 the art critic Brian Sewell published his memoirs, in which he claimed that he was Heseltine's illegitimate son, born in July 1931 seven months after the composer's death. Sewell's mother, private secretary Mary Jessica Perkins (who subsequently married Robert Sewell in 1936), a Camden publican's daughter,[109][110] was an intermittent girlfriend, a Roman Catholic who refused Heseltine's offer to pay for an abortion and subsequently blamed herself for his death. Sewell was unaware of his father's identity until 1986.[111]

Legacy

Heseltine's surviving body of work includes about 150 songs, mostly for solo voice and piano. He also wrote choral pieces, some with instrumental or orchestral accompaniment, and a few purely instrumental works.[112] Among lost or destroyed works the musicologist Ian Copley lists two stage pieces: sketches for the abandoned opera Liadain and Curither, and the draft of a mime-drama Twilight (1926) which Heseltine destroyed on the advice of Delius.[113][114] Music historian Stephen Banfield described the songs as "polished gems of English art song forming a pinnacle of that genre's brilliant brief revival in the early 20th century ... [works of] intensity, consistency and unfailing excellence".[106] According to Delius's biographer Christopher Palmer, Heseltine influenced the work of fellow-composers Moeran and Orr, and to a lesser extent Lambert and Walton, primarily by bringing them within the Delius orbit. In the case of the latter pair, Palmer argues, "those reminiscences of Delius which crop up from time to time in [their] music ... are more probably Delius filtered through Warlock".[115]

Heseltine biographer Brian Collins considers the composer a prime mover in the 20th-century renaissance of early English music;[116] apart from much writing on the subject, he made well over 500 transcriptions of early works. He also wrote or contributed to ten books, and wrote dozens of general music articles and reviews.[13] Many years later, Gray wrote of Heseltine: "In the memory of his friends, he is as alive now as he ever was when he trod the earth, and so he will continue to be until the last of us are dead".[117] During his Eynsford years, Heseltine had provided his own epitaph:

Here lies Warlock the composer

Who lived next door to Munn the grocer.

He died of drink and copulation,

A sad discredit to the nation.[118]

Music

Influences

In the early 20th century the German-influenced 19th-century song-writing traditions generally followed by Hubert Parry, Charles Villiers Stanford, Edward Elgar and Roger Quilter, were in a process of eclipse. For composers such as Ralph Vaughan Williams and George Butterworth, English folk-song became a dominant feature of their work;[119] at the same time, songwriters were seeking to extend their art by moving beyond the piano to develop richer forms of vocal accompaniment.[120] Thus, as Copley observes, at the outset of his career as a composer Heseltine found in song-writing a dynamic ambience, "within which he could express himself, or against which he could react".[119]

By the time Heseltine began composing seriously, around 1915–16, he had started to shake off the overwhelming influence of Delius. He had discovered English folk-song in 1913, his Oxford year, and had begun to study Elizabethan and Jacobean music.[121] In 1916 he came under the spell of Van Dieren, whose influence soon exceeded that of Delius and led to a significant development in compositional technique, first evident in the Saudades song cycle of 1916–17.[122] Gray writes that from Van Dieren, Heseltine "learned to purify and organise his harmonic texture ... and the thick, muddy chords which characterised the early songs gave place to clear and vigorous part-writing".[123] "In 1917–18 Heseltine's passion for Celtic culture, stimulated by his stay in Ireland, brought a new element to his music, and in 1921 he discovered Bartók.[124] A late passion was the music of John Dowland, the Elizabethan lutenist, one of whose dances he arranged for brass band.[125] These constituent parts contributed to the individual style of Heseltine's music.[13][122] Gray summarised this style thus;

They [the differing elements] are fused together in a curiously personal way: the separate ingredients can be analysed and defined, but not the ultimate product, which is not Dowland plus Van Dieren or Elizabethan plus modern, but simply something wholly individual and unanalysable—Peter Warlock. No one else could have written it.[126]

Apart from those within his circle, Heseltine drew inspiration from other composers whose work he respected: Franz Liszt, Gabriel Fauré, and Claude Debussy. He had, however, a particular dislike for the works of his fellow song-writer Hugo Wolf.[16] Heseltine's songs demonstrate moods of both darkness and warm good humour, a dichotomy that helped to fuel the idea of a split Warlock/Heseltine personality. This theory was rejected by the composer's friends and associates, who tended to see the division in terms of "Philip drunk or Philip sober".[4][13]

General character

In a summary of the Warlock oeuvre, Copley asserts that Heseltine was a natural melodist in the Schubert mould: "With very few exceptions his melodies will stand on their own ... they can be sung by themselves with no accompaniment, as complete and satisfying as folk-songs".[127] Copley identifies certain characteristic motifs or "fingerprints", which recur throughout the works and which are used to depict differences of mood and atmosphere: anguish, resignation but also warmth, tenderness and amorous dalliance.[128] The music critic Ernest Bradbury comments that Heseltine's songs "serve both singer and poet, the one in their memorably tuneful vocal lines, the other in a scrupulous regard for correct accentuation free from any suggestion of pedantry".[122]

In musical parlance Heseltine was a miniaturist, a title which he was happy to accept in disregard of the sometimes derogatory implications of the label: "I have neither the impulse nor the ability to erect monuments before which a new generation will bow down".[116][129] He was almost entirely self-taught, avoiding through his lack of a formal conservatory training the "teutonic shadow"—the influence of the German masters.[130] To the charge that his technique was "amateurish",[131] he responded by arguing that a composer should express himself in his own terms, not by "string[ing] together a number of tags and clichés culled from the work of others".[15] His compositions were themselves part of a learning process; The Curlew song cycle originated in 1915 with the setting of a Yeats poem,[132] but did not reach completion until 1922. Brian Collins characterises this work as "a chronicle of [the composer's] progress and development".[116]

Critical appraisal

Heseltine's music was generally well received by public and critics. The first Warlock compositions to attract critical attention were three of the Dublin songs which Rogers published in 1918. William Child in The Musical Times thought these "first rate", and singled out "As Ever I Saw" as having particular distinction.[133] In 1922, in the same magazine, the short song cycle Mr Belloc's Fancy was likewise praised, especially "Warlock's rattling good tunes and appropriately full-blooded accompaniment".[134] Ralph Vaughan Williams was delighted with the reception accorded to the Three Carols, when he conducted the Bach Choir at the Queen's Hall in December 1923.[135] Early in 1925 the BBC broadcast a performance of the Serenade for string orchestra written to honour Delius, a sign, says Smith, that the music establishment was beginning to take Warlock seriously.[136] Heseltine himself noted the warmth of the Prom audience's reaction to his conducting of the Capriol Suite in 1929: "I was recalled four times".[94]

After Heseltine's death, assessments of his musical stature were generous. Newman considered some of Heseltine's choral compositions "among the finest music written for massed voices by a modern Englishman."[108] Constant Lambert hailed him as "one of the greatest song-writers that music has ever known",[137] a view echoed by Copley.[138] In a tribute published in The Musical Times, Van Dieren referred to Heseltine's music as "a national treasure" that would long survive all that was currently being said or written about it.[139] In subsequent years his standing as a composer diminished; Brian Collins records how public perceptions of Warlock were distorted by the scandalous reports of his private life, so that his musical importance in the inter-war years became obscured.[116] However, when the Peter Warlock Society was created in 1963, interest in his music began to increase.[122] Collins acknowledges that the Warlock output includes much that can be dismissed as mere programme-fillers and encore items, but these do not detract from numerous works of the highest quality, "frequently thrilling and passionate and, occasionally, innovative to the point of being revolutionary".[116]

Writings

As well as a large output of musical journalism and criticism, Heseltine wrote or was significantly involved in the production of 10 books or long pamphlets:[140]

- Frederick Delius (1923). John Lane, London

- Thomas Whythorne: An unknown Elizabethan composer (1925). Oxford University Press, London (pamphlet)

- (Editor) Songs of the Gardens (1925). Nonesuch Press, London (anthology of 18th-century popular songs)[141]

- (Preface) Orchésography by Thoinot Arbeau, tr. C.W. Beaumont (1925). Beaumont, London

- The English Ayre (1926). Oxford University Press, London

- (with Cecil Gray) Carlo Gesualdo, Prince of Venosa: Musician and Murderer (1926). Kegan Paul, London

- Miniature Essays: E.J. Moeran (1926). J.& W. Chester, London (pamphlet, issued anonymously)

- (with Jack Lindsay) Loving Mad Tom: Bedlamite verses of the 16th and 17th centuries (1927). Fanfrolico Press, London (musical transcriptions by Peter Warlock)

- (Editor, joint with Jack Lindsay) The Metamorphosis of Ajax (1927). Fanfrolico Press, London

- (Editor under the name "Rab Noolas") Merry-Go-Down, A Gallery of Gorgeous Drunkards through the ages (1929) (anthology)

At the time of his death Heseltine was planning to write a life of John Dowland.[142]

See also

- Voices (1995 film), loosely based on Warlock

- List of composers in literature ('Peter Warlock')

Notes and references

Notes

- An attempt in 2001 by members of the Peter Warlock Society to re-enact the naked ride was thwarted by local police, who threatened to arrest anyone who tried it.[34]

- Smith records that the reason for the choice of name is unknown. A warlock is a male witch, a sorcerer or magician. The choice precedes Heseltine's active interest in occult practices; Smith surmises that, at a time when black magic and the occult were popular topics, Heseltine may have been subconsciously influenced towards this choice.[42]

Citations

- Smith 1994, p. 2

- Smith 1994, p. 4

- Parrott, pp. 10–11

- Smith, Barry (2004). "Heseltine, Philip Arnold". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/33843. Retrieved 2 September 2012. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Parrott, p. 18

- Davies, Rhian (29 June 2006). "Peter Warlock". BBC Mid Wales. Archived from the original on 11 July 2012. Retrieved 2 September 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - Parrott, p. 20

- Smith 1994, pp. 17–18

- Parrott, pp. 20–23

- Gray 1934, pp. 36–37

- Smith 1994, pp. 19–21

- Smith 1994, pp. 22–23

- Smith, Barry (2007). "Warlock, Peter (Heseltine, Philip Arnold)". Grove Music Online. Retrieved 2 September 2012.

- Smith 1994, pp. 24–25

- Cockshott, Gerald (July 1940). "Some Notes on the Works of Peter Warlock". Music & Letters. 21 (3): 246–258. doi:10.1093/ml/XXI.3.246. JSTOR 728361.

- Cockshott, Gerald (March 1955). "E.J. Moeran's Recollections of Peter Warlock". The Musical Times. 96 (1345): 128–30. doi:10.2307/937140. JSTOR 937140.

- Smith 1994, pp. 31–36

- Parrott, pp. 13–14

- Beecham, p. 175

- Beecham, pp. 175, 179

- Smith 1994, p. 38

- Smith 1994, p. 55

- Smith 1994, p. 60

- Anderson, Robert. "Fennimore and Gerda". Grove Music Online. Retrieved 24 September 2012.

- Smith 1994, pp. 68–69

- Gray 1934, p. 97

- Fenby (ed.) 1987, p. 2

- Fenby (ed.) 1987, pp. 3–9

- Heseltine, Philip (March 1915). "Some Notes on Delius and His Music". The Musical Times. 56 (865): 137–42. doi:10.2307/909510. JSTOR 909510.

- Fenby (ed.) 1987, p. 11

- Smith 1994, p. 70

- Smith 1994, pp. 71–72

- Copley 1979, p. 23

- "Naked Capers". The Peter Warlock Society. Retrieved 6 October 2012.

- Smith 1994, pp. 76–77

- Smith 1994, pp. 84–85

- Smith 1994, pp. 90–94

- Smith 1994, pp. 94–97

- Gray 1934, p. 131

- Beecham, pp. 175–77

- Smith 1994, pp. 98–99

- Smith 1994, pp. 103–04

- Parrott, p. 44

- N. Heseltine, p. 123

- Parrott, pp. 24–25

- Smith 1994, pp. 106–07

- Smith 1994, pp. 110–20

- Smith 1994, pp. 125–27

- Smith 1994, pp. 130–34

- Parrott, p. 72

- ApIvor, pp. 187–195

- Parrott, p. 31

- Smith 1994, p. 136

- Smith 1994, pp. 145–51

- Palmer, pp. 174–75

- Smith 1994, pp. 160–63

- Beecham, p. 180

- Smith 1994, pp. 158–59

- Heseltine, Philip (April 1920). "Delius's New Opera". The Musical Times. 61 (926): 237–240. doi:10.2307/909611. JSTOR 909611. (subscription required)

- "Warlock: The Curlew". Discovering Music. BBC Radio 3. 4 June 2014. Retrieved 29 May 2016.

- Rayborn, p. 160

- Kemp, p. 46

- Smith 1994, pp. 172–73

- Smith 1994, pp. 176, 185

- Smith 1994, p. 188

- "Life and Works". The Peter Warlock Society. Retrieved 18 September 2012.

- Smith 1994, pp. 187, 217

- Smith 1994, p. 216

- Beecham, p. 9

- Smith 1994, p. 201

- Smith 1994, pp. 217–20

- Smith 1994, p. 203

- Smith 1994, pp. 191–93

- Parrott, p. 61

- N. Heseltine, p. 107

- Smith 1994, pp. 212–13

- Dibble, Jeremy (January 2011). "Moeran, E(rnest) J(ohn)". Moeran, Ernest John. The Oxford Companion to Music Online edition. ISBN 978-0-19-957903-7. Retrieved 19 September 2012.

- Parrott, p. 96

- Smith 1994, pp. 222–27

- Gray 1934, pp. 254–55

- Hamnett, Nina (1955). Is She a Lady? A problem in autobiography. Allan Wingate. Retrieved 27 June 2020.

- Smith 1994, pp. 220–26

- Smith 1994, pp. 234–35

- Smith 1994, pp. 244, 250

- Smith 1994, pp. 249–50

- Smith 1994, pp. 251–52

- Smith 1994, pp. 253–56, 263

- Smith 1994, p. 259

- Beecham, pp. 200–01

- Jenkins, p. 43

- Fenby 1981, pp. 69–70

- Fenby (ed.) 1987, pp. 38–63

- Parrott, p. 93

- Smith 1994, p. 263

- Copley 1979, p. 141

- Copley 1979, p. 18

- Smith 1994, pp. 269–70

- ApIvor, Denis (1985). "Philip Heseltine: A Psychological Study". Music Review (46): 118–32.

- Smith 1994, pp. 274–75, 278

- Parrott, p. 37

- Smith 1994, pp. 276–80

- Gray 1934, p. 290

- Gray (1934), p. 295

- Smith 1994, pp. 281–83

- Parrott, pp. 34–41

- Banfield, Stephen (January 2001). "Moeran, Warlock and Song". Tempo. New series (215): 7–9. doi:10.1017/S0040298200008196. JSTOR 946634. S2CID 144734231.

- Wintle, Angela (24 November 2012). "Brian Sewell: My family values". The Guardian. Retrieved 21 April 2018.

- Copley, I.A. (October 1964). "Peter Warlock's Choral Music". Music & Letters. 45 (4): 318–336. doi:10.1093/ml/45.4.318. JSTOR 732851.

- "Sewell, Brian Alfred Christopher Bushell (1931–2015), art critic and broadcaster | Oxford Dictionary of National Biography".

- Angela Wintle (22 March 2015). "Brian Sewell: 'My biggest fear is mansion tax'". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- Sewell, pp. 17–23

- Copley 1979, pp. 295–309

- Gray 1934, p. 142

- Copley 1979, pp. 291–92

- Palmer, p. 162

- Collins, Brian (2001). "Peter Warlock's Music". The Peter Warlock Society. Retrieved 27 September 2012.

- Gray 1985, p. 261

- Smith 1994, p. 224

- Copley 1979, pp. 49–50

- Copley, I.A. (October 1963). "Peter Warlock's Vocal Chamber Music". Music & Letters. 44 (4): 358–370. doi:10.1093/ml/44.4.358. JSTOR 731397.

- Copley 1979, p. 34

- Bradbury, Ernest (1980). "Warlock, Peter". In Sadie, Stanley (ed.). New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. Vol. 24. London: Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-23111-2.

- Gray 1934, p. 140

- Parrott, p. 28

- Smith 1994, pp. 238, 246

- Gray 1934, p. 245

- Copley 1979, p. 255

- Copley 1979, pp. 260–63

- Gray 1934, p. 24

- Copley 1979, p. 253

- Copley 1979, pp. 263–64

- Smith 1994, p. 105

- The Musical Times review, November 1919, quoted in Copley 1979, p. 66

- The Musical Times review, September 1922, quoted in Copley 1979, p. 83

- Smith 1994, p. 214

- Smith 1994, p. 228

- Smith 1994, p. 289

- Copley 1979, p. 265

- van Dieren, Bernard (February 1931). "Philip Heseltine". The Musical Times. 72 (1056): 117–19.

- Copley 1979, pp. 276–82

- Smith 1994, p. 229

- Copley 1979, p. 283

Sources

- ApIvor, Denis (1994). "Memories of The Warlock Circle". In Cox, David Vassall; Bishop, John (eds.). Peter Warlock: A Centenary Celebration. London: Thames Publishing. ISBN 0-905210-76-X.

- Beecham, Thomas (1975) [First published by Hutchinson & Co. in 1959]. Frederick Delius. Sutton, Surrey: Severn House. ISBN 0-7278-0099-X.

- Copley, I.A. (1979). The Music of Peter Warlock. London: Dennis Dobson. ISBN 0-234-77249-2.

- Fenby, Eric, ed. (Autumn 1987). "The Published Writings of Philip Heseltine on Delius" (PDF). The Delius Society Journal (94). ISSN 0306-0373. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 16 September 2012.

- Fenby, Eric (1981) [First published by G. Bell & Son Ltd in 1936]. Delius as I Knew Him. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 0-571-11836-4.

- Gray, Cecil (1934). Peter Warlock: A Memoir of Philip Heseltine. London: Jonathan Cape. OCLC 13181391.

- Gray, Cecil (1985) [First published by Home & Van Thal in 1948]. Musical Chairs, or, Between the Stools. London: The Hogarth Press. ISBN 0-7012-0642-X.

- Hamnett, Nina (1955). Is She a Lady? A problem in autobiography. Allan Wingate.

- Heseltine, Nigel (1992). Capriol for Mother. London: Thames. ISBN 0-905210-81-6.

- Jenkins, Lyndon (2005). While Spring and Summer Sang: Thomas Beecham and the Music of Frederick Delius. Aldershot, Hampshire: Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 0-7546-0721-6.

- Kemp, Ian (1987) [1983]. Tippett: the composer and his music (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-282017-6.

- Palmer, Christopher (1976). Delius: Portrait of a Cosmopolitan. London: Duckworth. ISBN 0-7156-0773-1.

- Parrott, Ian (1994). The Crying Curlew. Peter Warlock: Family & Influences. Llandysul, Dyfed: Gomer Press. ISBN 1-85902-121-2.

- Rayborn, Tim (2016). A New English Music. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co. ISBN 978-0-7864-9634-1.

- Sewell, Brian (2011). Outsider: Almost Always, Never Quite. London: Quartet Books. ISBN 978-0-7043-7249-8.

- Smith, Barry (1994). Peter Warlock: The Life of Philip Heseltine. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-816310-X.

External links

- Free scores by Peter Warlock at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- Voices at IMDb