Parramatta Female Factory and Institutions Precinct

The Parramatta Female Factory and Institutions Precinct is a heritage-listed conservation site in Parramatta, in the City of Parramatta local government area of New South Wales, Australia. The site was used as the historically significant Parramatta Female Factory from 1821 to 1848. After its closure, the main factory buildings became the basis for the Parramatta Lunatic Asylum (now the Cumberland Hospital), while another section of the site was used for a series of other significant institutions: the Roman Catholic Orphan School (1841–1886), the Parramatta Girls Home (1887–1974), the "Kamballa" and "Taldree" welfare institutions (1974–1980), and the Norma Parker Centre (1980–2008).

| Parramatta Female Factory and Institutions Precinct | |

|---|---|

c. 1826 watercolour painting of the Parramatta Female Factory | |

| Location | Parramatta, City of Parramatta, New South Wales, Australia |

| Coordinates | 33°48′03″S 151°00′00″E |

| Built | 1804– |

| Architect | |

| Architectural style(s) |

|

| Owner | NSW Ministry of Health |

| Official name | Parramatta Female Factory and Institutions Precinct; Parramatta Female Factory; Parramatta Lunatic Asylum; Roman Catholic Orphan School; Parramatta Girls Industrial School; Norma Parker Centre |

| Type | National heritage (conservation area) |

| Designated | 14 November 2017 |

| Reference no. | 106234 |

| Type | Listed place |

| Category | Historic |

| Official name | Cumberland District Hospital Group; Wistaria House Gardens; Cumberland Hospital; Mill; Female Factory; Lunatic Asylum; Psychiatric Hospital; Parramatta North Historic Sites |

| Type | State heritage (landscape) |

| Designated | 2 April 1999 |

| Reference no. | 820 / 811 |

| Type | Historic Landscape |

| Category | Landscape – Cultural |

| Builders | Watkins & Payten |

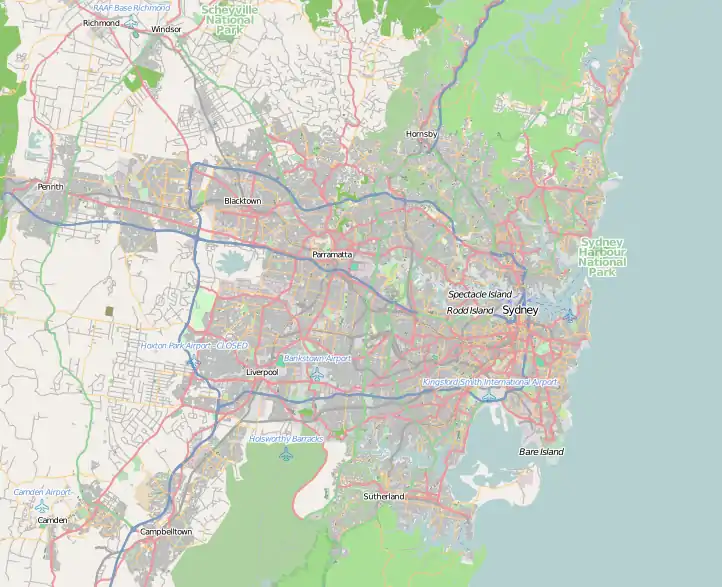

Location of Parramatta Female Factory and Institutions Precinct in Sydney | |

Designed under the influence and direction of Francis Greenway, James Barnet, William Buchanan, Walter Liberty Vernon, Frederick Norton Manning, Henry Ginn, and Charles Moore, the imposing Old Colonial, Victorian Georgian, and Classical Revival sandstone structures were completed during the nineteenth century.

The precinct was added to the Australian National Heritage List on 14 November 2017,[1] and its constituent parts (with separate listings for what was then the Cumberland Hospital and Norma Parker Centre) were added to the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 2 April 1999.[2][3]

History

The site is located on the Parramatta River in a transitional area between the Wianamatta Shale and Sandstone group soils. The topography is one of alluvial flats (flood plain) dropping away at the river.[2]

The Burramuttagal clan of the Eora Aboriginal people occupied and used the area for its rich resources – in game, fish, timber, plant foods and fibres.[2]

After Governor Phillip navigated the Parramatta River and reached the site of (later) Parramatta, he established a new settlement including a Government stockade, convict huts and areas for farm cropping and gardens slightly south and west of the subject area (in what would be the Government or Governor's Domain, later Parramatta Park.[2]

Early attempts at mechanised flour milling were unsuccessful in both Sydney and Parramatta. In 1800 Governor Hunter announced his intention to try a water mill at Parramatta. The site selected was the eastern bank of the river, near the Norma Parker Centre, where flat river stones formed a natural weir and causeway. Work digging the race and mill dam started in 1799. The mill took years to build. The Rev. Samuel Marsden was superintendent of public works at Parramatta and supervised its construction until 1803. Governor King brought from Norfolk Island a convict millwright, Nathaniel Lucas, and Alexander Dolliss, master boat builder, to assist in that year. They found the earlier construction poor and had to rebuild it. It finally opened in 1804.[4][2]

Indigenous history

The Burramatta people have lived on the upper reaches of the Parramatta River, including the land of the Parramatta Female Factory and Institutions Precinct, for at least 60,000 years.[5] The Burramatta are part of the Darug clan who occupy the Cumberland Plain and nearby areas of the Blue Mountains. The Darug consists of coastal, hinterland and mountain groups of which the Burramatta form a border grouping between coastal and hinterland communities.[6][1]

Prior to their dispossession and displacement, the Burramatta travelled seasonally across their land in groups of between 30 and 60 people with the Parramatta River being an important source of food, including eel, from which Burramatta (and later Parramatta) are etymologically derived ('place where the eels lie down').[5][1]

Early colonial history

The British settlement of Parramatta began soon after the arrival of the First Fleet in Sydney Cove in January 1788. Governor Phillip, acutely aware of the agricultural deficiencies of the area surrounding Sydney Cove and seeking to achieve self-sufficiency for the colony, explored parts of Sydney Harbour and nearby rivers, finding Parramatta the most suitable local for agricultural settlement, where he established a settlement in November 1788.[1][7]

British settlement of Parramatta from 1788 began the marginalisation of the Burramatta people from their lands, as occurred with other peoples throughout the Sydney Basin. Contact between the Burramatta and British was limited at first, but gradually some trade took place. Violence became more common as the British settlement grew larger and both groups clashed over resources and control.[1]

Conflict between the Darug clan and the British settlers escalated in the 1790s. This included several clashes close to the Parramatta settlement, most famously between an Indigenous group led by Pemulwuy and a settler force following a raid on Toongabbie in 1797.[8] Pemulwuy was wounded in this confrontation but later escaped from hospital to continue to be a leading figure in Indigenous resistance until being killed in 1802. Dispossession, disease and displacement led to widespread disruption of the lives of Burramatta people and their culture along with the rest of the Darug clan, contributing to the decline in armed resistance in the early 1800s.[1]

The first known British use of the area now known as the Parramatta Female Factory and Institutions Precinct was a land grant to former convict Charles Smith in 1792, who farmed wheat, maize and pigs for approximately a decade. Sometime in the early 1800s Smith sold his land to Reverend Samuel Marsden who would later be instrumental in the establishment of the Parramatta Female Factory.[1][9] Marsden, a pastor, magistrate and farmer, had previously supervised the construction of the Government Mill, close to what is now the Norma Parker Centre, with mill races extending north-west, through Smith's and now Marsden's land grant. The Government Mill was eventually finished but was never as successful as was initially hoped and was eventually sold and dismantled due to financial insolvency.[10] Marsden himself also built a competing Mill on land acquired from Smith.[1]

Between 1815 and 1835, annual feasts were held in Parramatta between indigenous people and prominent British settlers, including New South Wales Governors. These feasts would have almost definitely included Burramatta and other Darug people.[11] At some of these meetings, Governor Macquarie presented breast plates to prominent indigenous men (or at least those the Governor believed or wanted to be prominent), including to Bungaree with an inscription "Boongaree – Chief of the Broken Bay tribe – 1815".[12][1]

Imperfect and inconsistent British records suggest surviving Burramatta people still living around Parramatta up until the mid-1840s. Despite the British settlement, Darug and other indigenous people still reside in Parramatta today, with Western Sydney more broadly having the largest indigenous population in Australia.[5][1]

Parramatta Female Factory (1821–1848)

The practical difficulties of establishing a colonial settlement in NSW meant that accommodation for convicts was a much lower priority than essential works such as those relating to food production and transport. Principal Chaplain the Rev.Samuel Marsden had expressed concern over many years at the lack of accommodation for female convicts, thus forcing them into prostitution to pay for private shelter. The problem grew with increased numbers of women sentenced into transportation. The upper floor of the first Parramatta Gaol was used from 1804 to provide a place of confinement and work for convict women spinning wool but they were rarely kept working beyond one o'clock and there were no cooking facilities. Because it provided employment for them, it became known as the Female Factory and this term continued to be used for all subsequent prisons for female convicts.[13][2]

Macquarie announced in March 1818 that accommodation for female convicts would be built. With the foundation stone laid in July work commenced, being undertaken by Parramatta contractors Watkins & Payten. The Factory covered four acres (1.6ha) with the main building three storeys high. Institutional use of the site commenced in February 1821 with the transfer of 112 women from the old factory above the gaol to the new. Commissioner Bigge, investigating Macquarie's administration, was highly critical at the lack of priority given to the project but also critical that it was too elaborate, believing that a walled enclosure of a zero point six one hectares (one point five acres) at the old site with timber buildings for accommodation and a work room would have been sufficient.[2]

The new building, intended for 300 women, was built "at the extremity of a large, uninclosed tract of sterile ground" adjoining the river, which in flood came close to the wall of the new Factory. The cost was A£4,800, increased by A£1,200 for perimeter wall and flood protection measures. Proximity to the river was important because of the intended occupation of the women in spinning flax and bleaching linen, though Bigge doubted that this was sufficient reason to build so close to the river and within 27 metres (30 yd) of Old Government House on the other side of the river.[2]

Bigge's report included recommendations for managing the Factory, suggesting a married women rather than a married man would be a more appropriate manager and she could live in a house within view of the factory (but not within it). Separation of newly arrived women from those sent to the factory for punishment was essential and he recommended that a new range of sleeping rooms and work rooms be built. Sewing clothing and making straw hats should be added to the spinning and carding work to occupy their time.[2]

The desire to classify and segregate the women led to their division into three classes and construction of a penitentiary enclosure to accommodate 60 women of the third or penal class, in 1826. A two-storey building, probably designed by William Buchanan, was erected for the worst class of prisoners to the north-west of the main building and enclosed with a small yard.[2] Later in the 1860s this building was modified and the first floor removed to make a ward "for imbeciles and idiots", but it survives as the most substantial remnant of the Female Factory[14] (today this is referred to as Building 105).[2]

Once built, the Parramatta Female Factory had to be administered in a manner that improved convict women's industriousness and morality. Throughout the operation of the Parramatta Female Factory, administration often failed to meet high expectations, as moral purpose came into conflict with personality conflicts and monetary gain. The first superintendent, Francis Oakes, resigned following clashes with the local magistrate, Henry Douglas.[15] Later, husband-wife or mother-son pairs became the norm, providing early Australian examples of middle-class women taking on authoritative positions in colonial society. This male-female collaboration was also temporarily mirrored in the formation of a Board of Management and Ladies' Committee in Governor Darling's colonial administration.[1][16]

This two-person administration system continually ran into problems. The managers Elizabeth and John Fulloon were accused of fraternisation, neglect and maladministration. Matron Ann Gordon was dismissed for her husband's fraternisation and the convict women's immoral behaviour, and a Mrs Leach and Mr Clapham clashed even before they left England and did not stop until they were dismissed by Governor Gipps.[1][17]

Shortly before leaving for Britain in 1837, Governor Gipps was given authority to improve the separation of prisoners, especially the penal class. His predecessor Governor Bourke, had authorised the construction of a new wing at the Female Factory but work had not started. Gipps was able to modify the proposal, incorporating the newest trend in British prisons, the American Separate System of solitary cells. His modifications included removing windows on the ground floor to increase punishment and reducing cell sizes, changes which horrified the British designers. Gipps was instructed to cut windows into the ground floor punishment cells. The three-storey cell block was built between 1838 an 1839 to the south of the original Female Factory complex. The increased punishment capacity at Parramatta meant that the government could end transportation of women to Moreton Bay (later Brisbane). It had been the destiny of nearly 300 females who had been transported for colonial crimes. Women with colonial sentences now came to Parramatta.[2]

By 1830 the Female Factory was one of a number of institutions where convicts were employed, although it was the only one for women. It was staffed by a matron, storekeeper, clerk, four assistants to matron, a portress, gate keeper and constable and seven monitresses. Dissatisfaction with rations in 1827 led to a revolt among the women, who broke out and raided the bakers, gin shops and butchers in Parramatta. Such unrest usually coincided with overcrowding and declining conditions.[2]

The report of the Board of Management of the Female Factory for the first half of 1829 reported that there were 209 women in the First class; 142 in the Second; 162 in the Third or Penal class which included free women under sentence; 27 in hospital, making a total of 540 women and 61 children – 601 individuals in facilities designed for only 232. Of these women, only 133 women in the First class were eligible for assignment.[2]

The women had to stay in the factory and nurse their children until they were three years old when the children were transferred to the orphan schools. The authorities believed that many mistreated their baby so they can get out of the Factory when it died, an observation seemingly supported by 24 births and 22 deaths within six months. The Board recommended a nursery for the children when they were weaned so their mothers could go out early on assignment. The matron tried to keep women occupied but there was not always enough wool for the textile operations. A new building for a weaving shop was being built in 1829 but not yet completed. Changes to the rules on eligibility for tickets of leave enabled 21 women who were old and infirm and not eligible for assignment to be discharged in the first of many attempts to reduce overcrowding.[2]

There were 1315 women imprisoned in Sydney Gaol in 1830, 33 at Parramatta Gaol, 87 at Liverpool, 84 at Windsor, 91 at Newcastle, 21 at Penrith, 52 at Bathurst, all mostly held for misdemeanors. As the report on gaols noted almost all females were not actual criminals but prisoners of the Crown who had been assigned as servants but were not being returned to the Government. They were sent to the gaols as a place of security until an opportunity offered of forwarding them to the Factory in Parramatta. Such numbers reinforce the view that the Factory was hopelessly inadequate in size for the role it was expected to play within the convict system.[18][2]

The end of transportation from Britain in 1840 coincided with an economic depression that reduced employment prospects for assigned female servants. The factory was their only refuge. Those returned to the Government by masters who no longer needed them joined those unable to be assigned because of ill health or nursing children and those kept in the punishment divisions of the factory. Previously time at the factory had been for many a transitory experience, now it had become a destination.[2]

The 1841 census detailed 1339 people living at the factory – including 1168 women. It was more seriously overcrowded after the convict system ended than at its height. At its worst in the early 1840s it had 1339 people (1841), 1203 in 1842. In the summer of 1843 100 women rioted. They complained to the Governor of maladministration, inadequate food and overcrowded facilities. Corrupt staff were dismissed, and new policies introduced to give the women tickets of leave so they could leave the factory and work for themselves.[2]

Life in the Female Factory

Within the Parramatta Female Factory, convict women were separated into classes depending on factors such as their conduct and recidivism.[19] The system was devised by colonial authorities to reward good behaviour and punish bad behaviour. Convict women in the 'First Class' could earn money for the work they did, although some wages were kept until they left the factory.[20] First Class women could also be assigned to work in private homes, although whether that was better than working in the factory would have varied in each occurrence. In the mid-1820s, these women were also given better food and clothes, as well as permission to attend Church and receive visitors. First Class women could also marry, the officially sanctioned means to escape the factory, replacing the oversight of colonial authorities with a husband.[21] The factory acted as a marriage bureau where suitors undertook a three-day process to choose and woo their bride.[22] Given the advantages to both bride and groom in marriage, pragmatism likely triumphed over romance. Despite this, husbands were known to return their wives to the factory if married life proved less than agreeable.[1][23]

'Second Class' convict women received less clothes and food, and could not be assigned or receive visitors. Colonial authorities designed these classes to protect convict women from the dangers of early colonial life and the presumed descent into moral depravity that these women would surely resort to for survival. For the convict women, this involuntary protection regulated their lives while not necessarily providing safety and security.[1]

In contrast, the 'Third Class' was created to protect the colony from the convict women rather than the other way round. The women of the Third Class had committed crimes in the colony or broke the factory's rules. Annette Salt details several examples:[1][24]

Refusal to remain in their masters' service earned hard labour at the Factory for Sarah Brown, Mary Lee, Catherine Kiernan and Mary Draper.[...] Margaret Donnolly and Johanna Lawson for escaping from the Factory and stealing clothes while at large. Ann Hayes were sentenced by the Sydney Bench of Magistrates to twelve months' hard labour at the Factory for prostitution and being 'a pest to society'.[1]

For most of the factory period, Third Class women were given less food and fewer clothes than other women, and were in the worst of the accommodation. Their labour was often harder and they could keep none of their wages.[1]

Work inside the factory for all classes largely revolved around the making of cloth and linen.[25] Other women worked on the operation of the factory itself, including in cooking and washing; some of these services were extended to the public. In addition, women could work do other work such as needlework or hat-making. The workers of the Female Factory were susceptible to the supply and demand of labour in the fledgling colony and often went without work when the production costs were too high or their labour not in demand.[1]

The Female Factory also included a hospital. The hospital could be accessed not only by factory women but also, for most of its lifespan, by all colonial women. The most common conditions included dysentery, eye infections, fungal infections, diarrhoea and fever. The hospital was also the place where factory women gave birth.[1]

The model of female factory administration was often superseded by the reality of overcrowding and poor rations. Designed for 300 women, after the 1820s the number of women greatly exceeded this. Estimates are difficult to confirm, but it is likely that numbers varied between 400 and 1200 women over the lifespan of the factory.[26] In addition to the women, hundreds of children also lived at the factory with their mothers. An increase in numbers, combined with poor administration, meant sleeping quarters, and food and clothing allocations would have been strained to breaking point. Overcrowding was also evident in the hospital at the Parramatta Female Factory, although this would have been mirrored in the other early colonial hospitals.[1][27]

Order was not always maintained at the Parramatta Female Factory with several recorded instances of riots. In 1833, mass hair-cutting, despised by convict women, seemed to have precipitated a riot, as described by Reverend Marsden:[1][28]

I told you when I was in Sydney on Tuesday that I expected the women in the Factory would excite a riot again. They began on Wednesday night to be very troublesome and this morning they struck work. This was also the day for their hair to be cut. They one and all are determined not to submit to this operation. 40 Soldiers with their officers were ordered to attend the constables to the factory. Anderson and I went before, Captain Westmacott gave directions for the soldiers – the women had collected large heaps of stones and as soon as we entered the third class they threw a shower of stones as fast as they possibly could...

From Female Factory to Lunatic Asylum

The end of transportation of convicts to New South Wales in 1840 did not immediately cause the closure of the Parramatta Female Factory and in fact led to an increase in numbers, as other female factories were closed down and women were relocated to Parramatta.[29] However, continued poor administration, disorder and an increased demand for female labour in the colony led to a dramatic decrease in numbers in the factory by the mid-1840s.[30] The high cost of the factory's operation meant that it was now seen as an untenable drain on colonial resources.[1]

By 1847 there were only 124 women and 48 children left inside – fourteen percent of the numbers of five years previous. Half these women were under sentence for crimes committed in the colony. A new superintendent and matron were appointed. Edwin Statham and his wife, appointed in the closing months of the Female Factory, remained at the institution until their retirement thirty years later. Their son remembered the big drains that ran from the old water mill past the Factory and into the river. The entrance to the river was a stone-covered drain, the top end of which was closed by a vertical grating but the lower end was open – and at four feet high and three foot wide provided ample opportunity for adventurous boys to explore. It later became part of the sewerage system of the Hospital for the Insane. Sections of the mill race including the diversion have been uncovered through recent archaeological investigations.[31][2]

While female factories were in decline, the demand for lunatic asylums was increasing. The mentally ill in New South Wales had been held in Castle Hill (closed in 1825), Liverpool and a new asylum at Gladesville (Tarban Creek), but even the latter was already overcrowded less than a decade after its construction.[32] Given that the Female Factory was both a penitentiary and a refuge, the factory was well-suited to transition its function to housing the mentally ill. The transition was progressive, and convict women and the destitute continued to be housed in the joint factory and asylum for a time, however by 1848 the Parramatta Female Factory had become the Parramatta Lunatic Asylum.[1]

The existence of a Lunatic Asylum on the site was a continuum of the institutional history of the Female Factory, but also retained a connection to the gendered nature of the institutions on the site. Despite the fact that more men than women were committed to asylums in the Australasian colonies, women were regarded as having a propensity towards insanity, and this was entrenched in the discourse of institutions.[33] The observation that convict women had excitable tempers reflected a long standing belief that women's emotions were more easily disturbed, and the need for care and control of women in the form of an asylum also applied to mental institutions.[1]

Parramatta Lunatic Asylum (1848–1983)

The conversion to the Parramatta Lunatic Asylum occurred during the slow transition of the submergence of mental illness inside criminality and poverty towards the identification and treatment of mental illness as a distinct medical condition.[34] Parramatta was slow to transition its approaches, as the designated asylum for the criminally insane and 'incurable' cases. Other asylums, particularly Gladesville and the Callan Park Hospital for the Insane (established in 1885), were more advanced in their treatment.[1][35]

Housing the criminally insane darkened the operations and reputation of the asylum. The second superintendent, Dr Richard Greenup (1852–1866), was stabbed in the abdomen by criminally insane patient James Cameron, and died two days later.[36] Tragically, Greenup had been passionate in improving the conditions for patients, including lessening confinement and other restrictions.[1]

Compounding matters, staff were relatively poorly paid, expected to work long hours with little leave and often slept in the dormitories with the patients.[37] The Asylum was also frequently overcrowded, despite numerous expansions and constructions. These constructions also included the demolition of much of the former Female Factory. These factors combined with societal attitudes towards the mentally ill led to mistreatment of patients by some staff, although successive superintendents often sought to curb such behaviour.[1][38]

In 1872, Frederick Norton Manning became Inspector General for all lunatic asylums in New South Wales. His term in office saw a major program of new building, changes to layout and replacement of earlier structures. The site was also expanded to take in land further north.[2] Subsequent developments in the twentieth century were largely to the north of the former Female Factory site.[2]

Conversely, other patients would have had more positive experiences, especially compared to their treatment in society at the time. Even in the early stages of the Asylum, some patients were allowed to freely access the grounds. Patients were kept occupied through work, including in the Asylum's farm established in the Governor's domain, beautification of the grounds, and recreational activities that included dances and eventually cinema.[1]

Throughout its operation, like other asylums and mental hospitals, Parramatta was often the subject of criticism and reform movements as government and societal attitudes towards the treatment of mental illness evolved. The visiting Catholic Bishop of Hobart, Dr Robert Willson, in 1863 described the asylum as "a frightful old factory prison at Parramatta, with its doleful cells and its iron bar doors, even for women", although the Bishop went on to compliment the staff: "great cleanliness and order were evident in every part; no doubt the best is done for the patients, under the existing circumstances".[39] The evolution of mental health care is reflected in the changing names of the Lunatic Asylum; it was renamed progressively the Hospital for the Insane in 1869, Parramatta Mental Hospital in 1915, Parramatta Psychiatric Centre and then finally the Cumberland Hospital in 1983.[1][40]

Reforms, constructions and staff changes followed many instances of public discussion, scandal and debate. However, the most significant change occurred following the broader public debates and government inquiries into mental health treatment in the 1950s and 1960s, including the Stoller Report in 1955 and the Royal Commission of Callan Park Mental Hospital in 1961. What followed over the next several decades was the movement towards community outpatient treatment of mental illness and the subsequent decline in the need for inpatient treatment and residence. Reflecting this change, in 1995 the NSW Institute of Psychiatry moved into buildings formerly occupied by patients.[1][41]

Roman Catholic Orphan School (1844–1886)

In the latter years of the Female Factory, shortly before the establishment of the Lunatic Asylum, a Roman Catholic Orphan School was established on the site to the south of the original Female Factory area. It was one of many orphanages established in the colonies; in Sydney, the Female Orphans' Asylum was established in 1801 and Boys' Orphanage in 1819. The Roman Catholic Orphan School was originally established in Waverley in 1836 following agitation from the Catholic community that Catholic-born children were being housed in the Protestant-run Female and Boys Orphanages.[1]

The term 'orphan' can be misleading as many of the children placed into colonial and later 'orphanages' still had parents alive. Children were eligible for admission where they were "orphans of one or both parents; living with vicious and immoral parents or guardians; [or] as might relieve the distress of a large family".[42] The creation of the Orphan School was partially a consequence of the colonial government's choices about how to manage mothers in poverty. Many of the mothers of children in the Orphan School were housed at the adjacent Female Factory, with high numbers of Irish women convicts. This is believed to be the reason why the Orphan School was moved from Waverley to Parramatta in 1844.[43] This indicated the close link between the two institutions on the site. As convicts, mothers of the Female Factory were to have their children removed from their influence as unfit mothers, also allowing the women to be put to work in the Factory or out to service as part of the penal system.[1]

The term 'school' is also potentially misleading as while children did receive some education, the building itself was reminiscent of the adjacent Female Factory, in that it had a custodial design. The Sydney Herald described how:[1][44]

The new Orphan School adjoining the Factory is rapidly progressing, and will be ready for the roof in about six or eight weeks. It consists of four storeys, the lowest being intended as a storeroom of fifty feet, and the horizontal dimensions are about 56 x 22 feet... The school is to be walled in, the outhouses being ranged round the limits of the enclosure.

The school employed a matron, surgeon, master/boys' teacher, assistant matron/girls' teacher and female servants with annual funding provided by the colonial administration.[45] Initially, the Sisters of Charity visited the Orphanage and gave support on a voluntary basis, until 1849.[46] The children were taught basic skills in order that they could later be apprenticed. For authorities, the entire process could then turn the children from burdens on the state who were at risk of turning to delinquency and crime due to their poor family circumstances, into workers providing an economic benefit to the colony and learning the moral value of industriousness. Religious instruction at the school was also considered a core part of saving children from the poor choices of their parents.[1][47]

The theoretical purpose of the orphan school was overwhelmed by its continued underfunding. Following a visit in 1855 by the new Governor, William Denison, a government report found severe faults in both Roman Catholic and Protestant orphan schools, remarking that the "utter inefficiency of the Establishments, as now conducted, to produce any good effect upon the Children maintained in them".[1][48]

The report particularly criticised the poorly funded Roman Catholic orphan school, including sub-standard nutrition, lack of dining utensils, poor and few items of clothing, inadequate sanitation and bedding, non-existent education and overcrowding.[49] The children were locked in at night, potentially catastrophic in case of fire. The girls' education was substituted for laundry and other domestic work needed to keep the institution running. Boys were made to do heavy labour. The psychological impacts were immediate, with the report noting that:[50]

Instead of the exhuberant [sic] vivacity usually displayed by children just escaped from the confinements of school, we saw in general sluggishness. They stood or sat basking in the sun, instead of entering with spirit into the games common among boys of their age.

In 1859, in hope of improving the situation, John Bede Polding, Archbishop of Sydney asked three Sisters of the Good Shepherd (later known as Sisters of the Good Samaritan) to take residence at the orphanage as matron, sub-matron and girls' teacher.[1][51]

Despite this, in the successive years little changed. A visit by another Governor, Somerset Lowry-Corry, 4th Earl Belmore, in 1871 found that the buildings were "destitute of colour" and in a "disreputable state" and looking like a "half-gaol, half-lunatic asylum".[52] A report in the Sydney Mail, 3 December 1866, spoke of the difficulty of caring for the children in such conditions. It noted that there were now seven Sisters at the Orphan School:[1]

The greatest care is taken to keep the children healthy, and they all appear to be so; but the task must be a difficult one, for the accommodation at this place is in many respects most wretched. The dormitories are all too small. Some of them are crowded to such an extent that the beds are literally packed together; so that it is impossible to pass between them. The boys have a good school room, but the girls are so crowded that they have scarcely room to move. The nuns are as badly off for room as the children.

In 1873 a Royal Commission was established by the Premier Henry Parkes to examine child welfare institutions in New South Wales. The commissioners praised the matron, Sister Magdalene Adamson, for achieving outstanding levels of internal management and acknowledged a proficiency in teaching equal to "the ordinary unsectarian schools of the colony". Her administrative "vigour" was held up as a contrast to the government's laxity and bias. She was particularly commended for the "very great importance" she attached to knowing each child as an individual. Nevertheless, the Royal Commission found that the Orphan School was underfunded, with the buildings in a dilapidated state, and recommended that big institutions should be phased out in the colony. The barrack system would be abolished and state-dependent children would be fostered by selected families who would be paid just enough money to cover the child's expenses. This new approach was known as the boarding-out system.[1][53]

The continued chronic underfunding combined with the broader reform movement for boarding out children led to a stark reduction in numbers in the early 1880s at the Roman Catholic Orphan School. There were over 300 children at the start of 1880 but this had reduced to 193 by the end of 1883 and by the end of 1885, only 63 children remained. The Orphan School was closed in 1886 with the remaining children relocated to the St Vincent's Home in Manly.[1][54]

Parramatta Girls Industrial School (1886–1974)

The Parramatta Girls Industrial School (also known as the Parramatta Girls Home) was established on the grounds of the former Roman Catholic Orphan School to replace similar girls' institutions at Newcastle and Cockatoo Island in Sydney Harbour that were being closed down. The Girls School was designed to hold 'neglected' and 'wayward' girls. The New South Wales government saw it as its responsibility to play the role of caregiver and authoritarian in the lives of vulnerable girls, perpetuating an attitude that began with convict women being regarded as a responsibility of government. Girls were taught domestic work in what was envisioned to be a school-like environment run by a former headmaster of Parramatta Public School.[55] A high wall was built to prevent any escape by the girls, but the buildings themselves were not extensively modified, despite remaining in poor condition.[1][54]

Despite the intentions to create an educational, reformatory environment, what transpired over the next nearly hundred years at the Parramatta Girls Industrial School was a form of care emblematic of the treatment of children in institutions across Australia into the late 20th century. Residents of the Girls School experienced widespread abuse, both mental, physical and sexual, as well as a lack of emotional support and care essential to childhood development. The severity of the conditions experienced by children in care has only recently started to be recognised by the broader community, including through the 2004 Senate Report Forgotten Australians: A report on Australians who experienced institutional or out-of-home care as children and the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse, established in 2013. These reports, largely instigated by the courage of survivors to tell their stories, provide detailed descriptions of the suffering faced by young girls at the Industrial School.[1]

Over 30,000 girls were housed at the Parramatta Industrial School during its lifetime, holding approximately 180 girls at a time between the ages of 8 and 18, usually for a period of six months to three years.[56] From 1886 to 1974 the school went through a number of name changes, from Parramatta Girls Industrial School, to Parramatta Girls Training Home, then Parramatta Girls Training School. The function of the facility remained generally the same throughout these name changes. Girls were committed to the school for various reasons; they often came from other institutions, abusive homes, were designated by child welfare authorities to be 'neglected' or 'uncontrollable', and included Indigenous girls who were part of the Stolen Generations.[1]

An average of 7–10% of the girls were Indigenous or of Indigenous descent. The Stolen Generations arose from the forcible separation of Indigenous children from their families and communities since the very first days of the European occupation of Australia by governments and missionaries. In the late 19th century, this practice developed into a systematic and widespread attempt to assimilate Indigenous children into European society and to break their familial and cultural heritage. Parramatta Girls School was one of the institutions that Indigenous children were taken to after being removed from their parents.[1]

Around 86% of the girls in the school were committed on the basis of a complaint – the majority of complaints consist of "neglected", but also included "uncontrollable", "absconding" and "breach of probation". The committal of girls to the school by the government, on charges such as "neglected", criminalised many girls' experiences of trauma and poverty, reflecting the penal philosophy consistent through the history of the institution. The other 14% of girls were committed due to 'offences', mainly stealing.[57] There was little recognition that girls who were absconding and uncontrollable were often reacting to mistreatment at the hands of those around them, situations such as violent families, sexual abuse or poor treatment in the foster system.[58] Around 5–8% of girls were pregnant while in Parramatta; any sexual history was considered sufficient to indicate delinquency regardless of the circumstances under which the girls experienced it.[59] The Girls School brought together the histories on the site of the government's responsibility for women who had broken social conventions, in the Female Factory, as well as children who had come from unfit homes, as with the Orphan School.[1]

Many girls were from sole parent families, and their "neglect" was a consequence of the poverty their mothers experienced due to a lack of assistance from the social security system – it was not uncommon for girls in the home to have female ancestors who themselves had been residents of the institutions on the site such as the Female Factory. Welfare benefits were below the poverty line and families were scrutinised to determine whether they were morally deserving of assistance.[60] Up to a quarter of girls at the school had been admitted more than once, after being released into dysfunctional family situations, or foster homes or domestic work where they were treated poorly.[1][61]

Throughout its history, the Girls School functioned as a mix of a training school, for girls committed for welfare reasons, and a reformatory for girls with 'criminal' history. However, overcrowding at the school meant these lines were often blurred.[62] Once in the school, there was a particular focus on training the girls in domestic work – cooking, cleaning, sewing and laundry.[63] Much of the girls' training was to engage in the day-to-day labour of the school, including making and mending clothing, laundry and kitchen work, maintenance and cleaning.[64] This work was similar to that undertaken by convicts in the Female Factory. The domestic regime was meant to have a reformatory influence and mould the girls into useful candidates for domestic service placements and good citizens. The training of children in industrial schools filled the gap in the supply of domestic servants left by the end of convict transportation.[65] As time progressed there were increasing attempts to include academic schooling as part of the girls training, such as in response to the Public Institution Act 1901, but such educational options remained limited.[1][66]

Girls were punished for any perceived misbehaviour, even for minor misdemeanours. Punishments included beatings, harsh cleaning duties, 'standing out', where girls were required to stand at attention for hours on end, and segregation and isolation. Riots were a regular response by the girls to the poor conditions and treatment they experienced, including a riot on Christmas Day after a visit by the Minister for Education in 1941. For some girls, who had been committed from neglectful homes or a life on the streets, the school offered some security and protection. However, there were also instances of bullying and violence from other girls, as well as the punishment and abuse from staff.[67] In 1961 the government turned the Hay Gaol into an Institution for Girls designed to hold the worst behaved girls from Parramatta, reminiscent of the separate solution for Third Class women in the Female Factory.[1][68]

The Girls School was run by the New South Wales Government, and there were regular concerns with the management of the site throughout its history. Official reviews into the school occurred between 1889 and 1961, with one significant review in 1945 by Mary Tenison Woods recommending a number of positive improvements, such as better child guidance and educational opportunities. The New South Wales Government responded to the review by changing the name of the school from the Parramatta Girls Training Home to the Parramatta Girls Training School, but apart from this the buildings and most of the staff remained the same.[69] These conditions continued throughout the life of the institution. The discharge of girls from the school was essentially at the discretion of the Superintendent. As Bonney Djuric notes, "release from Parramatta did not always bring the anticipated freedom that girls yearned for, as many returned even more damaged to the difficult situations they had come from".[1][70]

The treatment of these girls reflected societal attitudes that had progressed little from the treatment of convict women at the Female Factory. The Senate Report[71] heard evidence that:[1]

Girls were treated far worse than boys... it was because of entrenched Victorian attitudes to fallen women and the view that girls were inherently more difficult to reform than boys...

The girls suffered from mental, physical and sexual abuse, as their testimony described:[72]

When I got to Parramatta I was told that they break my spirit at that time I didn't know what they meant... a Mr Gordon punched me in the face several times, my nose bled I was made to scrub large areas of cement with a toothbrush even in the middle of winter with nothing under my knees and my knees used to bleed and some times I would pass out with exhaustion. ... he [Mr Johnson] was a brutal man and within that week I had seen him bash and kick a girl that he had been molesting to try and induce a miscarriage...

The frequent riots at the institution throughout its operation gave government authorities and the wider community evidence of what was going on behind closed doors. However, it took a sustained campaign in the 1960s and 1970s by the Women's Liberation Movement, including Bessie Guthrie, for the institution to be closed down in the mid-1970s.[1][73]

The long-term psychological and physical effect of the institution on the girls has only recently been recognised by the broader community. As girls and in adulthood the women who lived in the school were commonly disbelieved and disregarded when trying to tell their stories, impacting on their self-worth as well as the community's recognition of their experiences. The surviving women often found difficulty in re-establishing relationships with their parents and forming healthy relationships with partners and/or children. The lack of meaningful training at Parramatta led many to be ill-prepared for the outside world and they struggled to manage permanent employment. Indigenous women had to deal with a break with their communities that made cultural and family connections difficult, if not impossible, to re-establish. The combination led many to destructive behaviour and crime, and many survivors suffer from severe mental health concerns such as depression and post-traumatic stress disorder.[74] In contrast, perpetrators largely avoided consequences for their actions.[1]

Kamballa and Taldree (1974–1980)

The phasing out of Parramatta Girls School did not completely abolish the need in the authorities' eyes for a place of detention for disruptive girls. When the Girls School was closed in 1974 a smaller facility was opened on the site named Kamballa. Kamballa was designed to provide a more reformative and humane institution for young female offenders in response to community concerns arising from the Girls School and other similar institutions across New South Wales.[75] According to the Government, Kamballa was meant to provide a similar function to Hay Girls Institution, for girls 15 to 18 with behavioural or emotional problems. However, the conditions were much improved from Hay, with fewer girls, a more relaxed atmosphere and no 'training' activities.[76] Programs like periodic detention and work release accompanied extensive renovations to the buildings to better improve rehabilitation outcomes. In the early period of this institution, young boys were also incarcerated in part of the institution called 'Taldree' before being relocated.[1]

Norma Parker Centre (1980–2008)

In 1980 Kamballa's main building was transferred to the Department of Corrective Services, and became the Norma Parker Centre.[76] The Centre was part of the corrections system, and functioned as a women's prison until 2008. The centre was named after the acclaimed social worker and educator, Norma Parker (1906–2004). Parker had previously lived at the Parramatta Girls School in 1943 as part of her work as a member of the Delinquency Committee of the Child Welfare Advisory Council.[77] In 1984 major alterations were carried out to the main block of the Centre to upgrade fire egress.[3] The Norma Parker Centre was closed on 24 February 2008 and has been largely vacant since.[78][1]

Description

The Parramatta Female Factory and Institutions Precinct is located within the grounds of the Cumberland Hospital and former Norma Parker Centre, bordered on the southern side by the upper reaches of the Parramatta River. The Precinct is approximately 7 hectares and contains buildings from the early 19th to late 20th century, some still occupied while others are vacant and dilapidated. Buildings remain on the site from the Female Factory, Roman Catholic Orphan School and Girls School, including the North-East and South-East Ranges, Sleeping Ward and some walls of the Female Factory, and from the Roman Catholic Orphan School and Girls School the Main Administration Building, Covered Way, South-West Range, Chapel, Laundry, Bethel House and the Gatehouse. The site also contained courtyard and assembly spaces associated with the Orphan and Girls Schools. Interspersed within these buildings are 19th century and more recent additions from the Parramatta Lunatic Asylum and its successors.[1]

While in a broader institutional parkland setting, the Precinct's buildings are relatively close and many areas have been paved or otherwise surfaced for the recent uses of the area. Some greenery and flora remains, particularly bordering the Parramatta River. The purposeful layout of former Female Factory, Lunatic Asylum, Roman Catholic Orphan School and Girls Industrial School have been impacted from late 20th century constructions and other additions when the design focus on confinement and isolation was no longer emphasised.[1]

Cumberland Hospital site

Cumberland District Hospital Group is located on and divided by the Parramatta River at North Parramatta. It is part of a larger institutional grouping set in a park-like setting by the river. It adjoins Parramatta Correctional Centre (former Parramatta Gaol/Jail) and the Norma Parker Centre / Kamballa (former Roman Catholic Orphan School and former Parramatta Girls Home).[2]

The site is occupied by a number of institutions namely Cumberland Hospital (Eastern Campus), the former Parramatta Mental Hospital, the former Asylum for the Insane. The main entrance to the complex is from Fleet Street. This forms the eastern boundary of the Hospital. Fleet Street in turn is accessed from O'Connell Street.[2]

Items of state significance within Cumberland Hospital are: Ward 1; Ward 1 Day Room; Accommodation Block for Wards 2 and 3; Ward 4 West Range; Ward 4 North Range; former Ward 5 South Range; Kitchen Block; former Day Room for Wards 4 and 5; Cricket Shelter; Administration Building; Wistaria House, Gardens and Siteworks; Sandstone Perimeter and Courtyard Block Walling and Ha Ha.[2]

The complex contains a rare and substantially intact, 1860s–1920s major public (designed) landscape with a large and remarkable diverse plant collection including particularly notable collections of mature palms, conifers and Australian rainforest trees.[79][2]

The complex sits in generous grounds which are both carefully designed, laid out and richly planted with ornamental species, both native and exotic, some representative and some rare. The palette of plants reflects those both in fashion and distributed by Charles Moore, Director of the Botanic Gardens Sydney (1848–96), via the State Nursery at Campbelltown in the 19th century. The range of shrubs and climbers also reflects the richness and variety of 19th and early 20th century garden design and array.[2]

There are 5 large specimens of Canary Island pine trees (Pinus canariensis) on the Riverside Drive lawn that were c.40m tall in 1991.[80] There is a rich array of conifers, such as Canary Island pines, more-rarely seen Indian chir pines (Pinus roxburghii), NSW and Qld. rainforest plants such as firewheel trees (Stenocarpus sinuatus), (some rainforest conifers such as Bunya (Araucaria bidwillii) and hoop pines (Araucaria cunninghamii), as well as South Pacific Island conifers, e.g. Norfolk Island pines (Araucaria heterophylla) and Cook's pine (Araucaria columnaris) grace the grounds. Rainforest fig trees such as Hill's fig (Ficus microcarpa var. Hillii), Port Jackson or rusty fig (Ficus rubiginosa) and Moreton Bay fig (Ficus macrophylla) are notable. Rarities such as the endangered Chilean wine palm (Jubaea chilensis) of which there are five on site and pony tail palm (Nolina sp.) occur along with less-rare palms such as the uncommon jelly palm (Butia capitata), more commonly-met Californian desert fan palms (Washingtonia robusta) and locally native cabbage tree palm (Livistona australis). New Zealand cabbage tree (Cordyline australis) grows outside the Main Administration building's portico on the site's north-western edge.[2]

Two large lawn areas form the heart of the site and its northern part, formerly the timber Male Wards (demolished except for the large Kitchen Block) and later chapel.[2]

Norma Parker Centre site

The main building is a three storey stone building designed by Henry Ginn in the late nineteenth century additions were made to this building and a series of wings and walkways added to the rear forming enclosed informal courtyards. The building are enclosed by brick walls and stone and iron picket fence.[3]

The Norma Parker Centre consisted of three separate accommodation areas: Winmill Cottage, Morgan House, and a section located above the facility's offices for women on Work Release.[3]

There are significant plantings, particularly mature trees such as Norfolk Island pine (Araucaria excelsa), Bunya pine (Araucaria bidwillii), jacaranda (Jacaranda mimosifolia), fiddlewood (Citharexylon quadrangulare) and others, including shrubs.[3]

Condition

The condition of buildings and other fabric in the Parramatta Female Factory and Institutions Precinct varies due to factors such as age and use of the buildings. Parts of the site have a relatively high level of intactness with their "original" layout, while other parts of the site are significantly modified from their original state. Generally the Precinct is in good condition able to demonstrate to a good capacity the National Heritage values of the place.[1]

The condition of the Female Factory buildings is variable. The main building from the Female Factory era was demolished following the site's conversion to a lunatic asylum, as were many other outbuildings. The demolition, as well as the replacement with Parramatta Lunatic Asylum and later hospital buildings mean the condition of the Female Factory site as a whole is reduced. The structures that remain from the Female Factory are three buildings (South-East and North-East Ranges and Penitentiary Sleeping Ward) along with some of the original enclosing walls. The original fabric of the three remaining buildings is in fair to good condition; however, these buildings have a number of recent additions to the original fabric which are intrusive. The South-East Range has a two storey sandstone addition to the eastern end of the building, one storey rendered addition to the western end of the building and intrusive additions on the northern and southern facades. The North-East Range has similar later additions.[81] The two ranges can still be read as a pair. The Sleeping Ward has been refurbished internally, and an original upper floor was removed in 1880. Parts of the original Female Factory walls remain though much of the original extend has been removed. While later constructions had the potential to damage the site's archaeological potential, recent works uncovering original footings from the Female Factory suggest that the potential remains relatively unaffected.[1]

Buildings and other fabric from the Roman Catholic Orphan School remain relatively intact given that the site's later functions required similar buildings so fewer alterations and/or demolitions occurred. Buildings that remain from that era include the Main Building, Covered Way, South-West Range, Chapel, Bethel House, Laundry, Gatehouse and play sheds, as well as enclosing walls. Some additions were made during the period of the Girls School, including the Hospital Wing, Industrial School building and additional cottages. Given the site's vacancy in the recent period, many of these buildings are in a relative poor external and internal condition. Some earlier buildings have undergone internal modification as a result of their continued used since being built in the 19th century. The Chapel and parts of the South-West Range were significantly damaged by fire in 2012 and have been sympathetically restored. Courtyards and open spaces from the Orphan and Girls School generally retain their original form, though may need some general gardening maintenance.[1]

Integrity

The overall integrity of the place is relatively high given the setting and retention of many buildings and fabric from key phases of the Parramatta Female Factory and Institutions Precinct with the noticeable exception of the Female Factory.[1]

As many of the buildings from the Roman Catholic Orphan School and Girls School remain, the integrity of the proposed heritage values under criterion (a) is relatively high. Observers are able to interpret aspects of the lives of institutionalised children and those suffering from mental illness, especially as relating to their confinement and enclosure. The use of parts of the site as Parramatta Lunatic Asylum and the later hospitals for over 150 years mean that newer buildings are spread throughout the site which somewhat reduced the ability to interpret the National Heritage values of the site, in particular of the Female Factory area, which has the greatest overlap with the Lunatic Asylum. The alterations to the site after the period of the Female Factory, including the demolition of the main building and newer constructions, make the interpretation of that period difficult. While this reduces the integrity of the value under criterion (a), the overall integrity remains fair. Overall the site satisfactorily expresses the National Heritage values identified.[1]

Heritage listing

The Parramatta Female Factory and Institutions Precinct is an outstanding example of a place which demonstrates Australia's social welfare history, especially regarding the institutionalisation of women and children over the 19th and 20th centuries. Institutionalisation was a core element of Australia's welfare system for over 150 years, where those receiving social services were placed in 'care institutions' which provided government services in a residential setting. Through this period, the Precinct was the site of the Parramatta Female Factory for women convicts, a Roman Catholic Orphan School for Catholic children, and finally the Parramatta Girls Industrial School, a home for girls seen as neglected or wayward, including children from the Stolen Generations. Together, these facilities provided shelter, education and oversight of thousands of women and children, but they were also often places of poor treatment and abuse. Women and children had a distinctive experience of institutionalisation, due to the particular moral judgment that was imposed on women and their children who lived in poverty or were considered to be outside social acceptability.[1]

Institutionalisation was progressively abandoned as a widespread model of care in the 1960s and 1970s in Australia, and the Apology to Forgotten Australians in 2009 highlighted the trauma experienced by children in institutions throughout Australia. The experiences of institutionalised women and children were frequently disregarded and dismissed while they were resident in institutions and afterwards. In light of the historical failure to recognise people's experiences, and the difficulty many former residents feel in telling their stories, the Precinct is able to present the experiences of these women and children in a way which allows the Australian community to recognise and witness the reality of institutionalisation. The Parramatta Female Factory and Institutions Precinct can act "as a bridge and a shared cultural space for witnessing nation-wide experiences of institutionalisation and incarceration" (Tumarkin 2016).[1]

The Precinct has retained buildings and spaces demonstrating the range of institutions on the site. These include original accommodation buildings and walls from the convict-era female factory, the original building of the Orphan School, and a number of buildings, walls and courtyards which were part of the Girls School, such as dormitories, assembly spaces, a chapel, and school and dining rooms. The remains of the Female Factory are rare in Australia, with few remnants of convict-era female factories left. Through this original fabric, the site demonstrates the distinctive experience of institutionalised women and children, who were subject to the system of care and control at the core of welfare institutions.[1]

The site also has significant archaeological potential in the form of remnants of the Female Factory, both of buildings previously on the site and artefacts associated with its day-to-day functions. This archaeological evidence has the potential to contribute to understanding of the lives of convict women, providing a perspective on their experiences which is not accessible from existing written sources.[1]

The place has outstanding heritage value to the nation because of the place's importance in the course, or pattern, of Australia's natural or cultural history.

The Parramatta Female Factory and Institutions Precinct is outstanding in its capacity to tell the stories of women and children in institutions over the course of Australian history. The Precinct demonstrates how colonial and state governments chose to address the perceived problem of vulnerable women and children, who they regarded as needing protection and control, through the use of institutions as a core element of the welfare system. In particular the Precinct provides a record of the experiences of convict women, and of how women and children as a class had a distinct experience of "benevolent" institutions, where the purpose and promise of care was far from the reality. Women living without the oversight of a husband or family were subject to moral judgment. Authorities saw it as necessary to step in as decision-maker and moral guardian, both of the women and of their children, who were seen as vulnerable to the consequences of poor parenting. Parramatta Female Factory and Institutions Precinct demonstrates how institutionalisation allowed for this duality of care and control to be enacted in a carefully administered environment.[1]

The legacy of penal approaches to caring for women and children, initiated in the Female Factory, persisted throughout the life of the Precinct in the way in which children's lives were regulated in the Orphan and Girls Schools. Over one hundred and fifty years the experiences, treatment and prejudices towards the women of the Female Factory, children of the Roman Catholic Orphan School and girls of the Industrial School, including Indigenous children of the Stolen Generations, showed a consistent theme of attempts at care limited by paternalism and poor treatment. The Precinct reveals the physical form which institutions took from the 19th to the 21st centuries. This in turn reflects the approaches to care that existed over the historical period, as well as providing a focal point for the stories of institutionalised women and children.[1]

This value is expressed in the remaining physical fabric of the Parramatta Female Factory (North-East and South-East Ranges, Penitentiary Sleeping Ward and remaining walls) and Roman Catholic Orphan School and Girls Industrial School (Main Administration Building, Covered Way, South-West Range, Chapel, Laundry, Bethel House and the Gatehouse), also known as the former Norma Parker Centre/Kamballa Site. This includes both the exterior and interior original fabric of the buildings and the curtilage they sit within, including but not limited to: the form of the South-West Range with its long, narrow, attic dormitory spaces; Female Factory, Orphan and Girls School site walls; enclosed courtyard and assembly spaces created by the South-West Range, Covered Way and fences; the Female Factory clock as used in Ward 1 of the Institute of Psychiatry; the relationship of the Orphan and Girls Schools with the wall of the Parramatta Female Factory, reinforcing the institutional qualities of the Schools; the perimeter wall of the Girls School, and the pairing of the Female Factory South-East and North-East Range. The values are not expressed in later intrusive additions to the original fabric.[1]

The place has outstanding heritage value to the nation because of the place's possession of uncommon, rare or endangered aspects of Australia's natural or cultural history.

The Parramatta Female Factory is a rare surviving example of its type in Australia. Female factories are rare sites; while there are a variation of sites associated with male convicts, such as gaols, probation stations, mines and convict-built infrastructure, there were fewer sites associated with convict women. In addition, there are few of these sites left. Nine of the 12 female factories which existed in colonial Australia are completely demolished. Places associated with the female experience of convictism are therefore rare. Parramatta Female Factory and Institutions Precinct demonstrates the nature of female convicts' experiences, and indicates social attitudes at the time to how these women should be managed. The existence of original buildings and walls on the Parramatta Female Factory site, their significance as a marker of the conditions and experiences of female convicts, and their national rarity mean the original Female Factory buildings are of outstanding value to the nation under this criterion.[1]

This value is expressed in the remaining physical fabric of the Parramatta Female Factory, being the North-East and South-East Ranges, Penitentiary Sleeping Ward and remaining walls.[1]

The Parramatta Female Factory and Institutions Precinct has outstanding potential to yield information that will contribute to an understanding of the lives of convict women in early colonial Australia, in particular their lives in institutions. The remnant built fabric relating to the Parramatta Female Factory is significant and further archaeological study of the area has the potential for finds of equal significance within the original boundaries of the Female Factory site, both of built fabric and of artefacts which reveal information about the daily lives of convict women.[1]

This value is expressed by the remnant built fabric and archaeological evidence found within the place relating to the original area of Parramatta Female Factory.[1]

The place has outstanding heritage value to the nation because of the place's potential to yield information that will contribute to an understanding of Australia's natural or cultural history.

The potential archaeological site covers the area which is encompassed by the Parramatta River, River Road, Eastern Circuit, Greenup Drive and Fleet Street, cutting west from Fleet Street back to the Parramatta River along the southern boundary of Lot 3 DP808446, which reflects the original Female Factory site. This area contains known and likely areas of archaeological potential, especially the hidden, lost and discarded artefacts of convict women, in addition to the remaining three buildings (North-East and South-East Ranges and Sleep Ward), the physical remnants of demolished Female Factory Buildings including the North-West Range and potential remaining features such as wells and wall footings.[1]

In Popular Culture

To New Shores is a 1937 film by Douglas Sirk starring Zarah Leander as an inmate.

See also

References

- "Parramatta Female Factory and Institutions Precinct (Place ID 106234)". Australian Heritage Database. Australian Government. Retrieved 25 August 2018.

- "Cumberland District Hospital Group". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Department of Planning & Environment. H00820. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC-BY 4.0 licence.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC-BY 4.0 licence. - "Norma Parker Correctional Centre". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Department of Planning & Environment. H00811. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC-BY 4.0 licence.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC-BY 4.0 licence. - DPWS, 2000, 48–9

- "The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples of Parramatta". Parramatta City Council. 2015. Retrieved 23 November 2015.

- Comber 2014, p. 18.

- Kass et al 1996, p. 9.

- Kohen, 2005.

- Yarwood, 1967.

- Kass et al 1996, p 61; Casey & Lowe 2014, pp. 41–42.

- Coomber 2014, p. 27.

- Attenbrow 2002, p. 61.

- DPWS, 2000, 57

- DPWS, 2000, 58

- Salt 1984, p. 56

- Salt 1984, p. 59

- Salt 1984, pp. 57–61

- DPWS, 2000, 58–9

- Salt 1984, pp. 70–74

- Salt 1984, pp. 71–73

- Salt 1984, pp. 80–81

- Hendriksen & Liston 2012, p. 45

- Salt 1984, pp. 87–88

- Salt 1984, pp. 86–87

- Salt 1984, pp. 102–109

- Salt 1984, pp. 50–53

- Salt 1984, pp. 111, 113

- Hendriksen & Liston 2012, p. 23

- Kass et al 1996, p. 135

- Salt 1984, p. 121

- DPWS, 2000, 60–62

- Kass et al 1996, p. 136; Smith 1999, p. 4

- Coleborne 2010, p. 38

- Garton 1988, pp. 21–23

- Smith 1999, p. 10; State Records of NSW 2016

- Phillips 1972

- Smith 1999, p. 13

- Smith 1999, p. 14

- Smith 1999, p. 12

- Australian Psychiatric Care Database 2011

- Smith 1999, p. 39

- Djuric 2011, p. 17

- Ramsland 1986, p. 57

- Ramsland 1986, p. 54

- Ramsland 1986, pp. 54–55

- Walsh 2001, pp 84–85

- Djuric 2011, p. 13

- Currey 1972; Ramsland 1986, p. 149

- Ramsland 1986, pp. 150–151

- Ramsland 1986, p. 151

- Walsh 2001, p. 88

- Ramsland 1986, p. 154

- Walsh 2001, pp 98–99

- Ramsland 1986, p. 200

- Kass et al 1996, p. 233

- Royal Commission into Institutional Responses into Child Sexual Abuse 2014, p. 7.

- Djuric 2011, p. 140.

- Djuric 2011, p. 143.

- Djuric 2011, pp 145, 146.

- Djuric 2011, p. 104.

- Djuric 2011, p. 148.

- Find and Connect, 2016b.

- Djuric 2011, pp. 70, 71.

- Djuric 2011, pp. 160–167.

- Djuric 2011, p. 172.

- Djuric 2011, p. 70.

- Djuric 2011, pp. 152, 153.

- Djuric 2011, pp. 116.

- Find and Connect, 2016a.

- Djuric 2011, p. 155.

- Senate Report 2004, p. 55.

- Senate 2004, p. 56

- Royal Commission into Institutional Responses into Child Sexual Abuse 2014, pp. 8–9.

- Royal Commission into Institutional Responses into Child Sexual Abuse 2014, pp. 28–32.

- Betteridge 2014, pp. 34–35.

- Djuric 2011, p. 135.

- Land & Henningham 2002.

- Tanner Kibble Denton Architects Pty Ltd; UrbanGrowth NSW (17 March 2017). "Parramatta North Historic Sites Consolidated Conservation Management Plan: Part B—Norma Parker Centre/Kamballa Site" (PDF). Retrieved 27 August 2018 – via UrbanGrowth NSW.

- Britton et al, 1999, 3

- Spencer, 1995, 250

- TKD 2014.

Bibliography

- Roman Catholic Orphan School Conservation Study. 1985.

- Adoranti, Kylie (2016). 'Repair and restoration works start on heritage buildings in North Parramatta'.

- Attenbrow, V. (2002). Sydney's Aboriginal Past: Investigating the Archaeological and Historical Records. Sydney: University of New South Wales Press.

- Bartok, Di (2011). Final Piece of Walking Track Finished.

- Bartok, Di (2010). Gadiel's Fight for the Gals'.

- Betteridge, Margaret (2014). "Parramatta North Urban Renewal and Rezoning: Baseline Assessment of Social Significance of Cumberland East Precinct and Sports and Leisure Precinct and Interpretive Framework" (PDF). MUSEcape. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- Britton, Geoffrey; Morris, Colleen (1999). North Parramatta Government Sites Landscape Conservation Plan.

- Bosworth, Tony (2017). 'Heritage Precinct sold for just $1 – land transferred to UrbanGrowth as apartment development looms'.

- Comber, Jillian (2015). "Parramatta North Urban Renewal: Aboriginal Archaeological & Cultural Heritage Assessment" (PDF). Comber Consultants. Retrieved 23 November 2015.

- Djuric, B. (2011). Abandon All Hope. Perth: Chargan My Book Publisher Pty Ltd.

- Heath, Laurel (1978). The female convict factories of New South Wales and Van Dieman's land: an examination of their role in the control, punishment and reformation of prisoners between 1804 and 1854.

- Heritage Division, OEH (1995). Hard Copy file S95/292/5.

- Heritage Group, Design Services, Department of Public Works & Services (2000). North Parramatta Government Sites Conservation Management Plan.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Heritage Group, NSW Dept. of Public Works (1991). Wistaria House and Gardens – Conservation Plan.

- Heritage Group, NSW Dept. of Public Works & Services (1997). Norma Parker Centre, Parramatta – Conservation Plan.

- Higginbotham, Edward & Associates (2010). Buildings 105A & 105B, Cumberland Hospital, Fleet Street, N. Parramatta NSW – Report on the Archaeological Monitoring Programme for the excavation of a drainage trench.

- Higginbotham, Edward & Associates (2006). Data Centre, Cumberland Hospital, Fleet Street, N Parramatta N.S.W.: Proposed Electrical Sub-Station, Generator and Cable Trenches. Permit Exemption Application.

- Higginbotham, Edward & Associates (1997). Report on Archaeological Monitoring Programme on Site A, Cumberland Hospital Eastern Campus, Parramatta NSW.

- Jackson Teece Chesterman Willis (1996). Cumberland Hospital – Tree Assessment.

- Kohen, J. (2005). "Pemulwuy (1750–1802)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. Retrieved 23 November 2015.

- Land, Clare; Henningham, Nikki (2002). "Parker, Norma Alice (1906–2004)". The Australian Women's Register. National Foundation for Australian Women / University of Melbourne. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- NSW Dept. of Public Works and Services (1985). Roman Catholic Orphan School Conservation Study.

- Parramatta Female Factory Project (2013). "Parramatta Female Factory Memory Project".

- Perumal, Murphy Alessi; Higginbotham, Edward; Britton, Geoffrey; Kass, Terry (April 2010). Conservation Management Plan & Archaeological Management Plan – Cumberland Hospital East Campus & Wisteria Gardens Parramatta.

- Spencer, Roger (1995). Horticultural Flora of South-Eastern Australia – Ferns, Conifers & their allies.

- Schwager, Brooks & Partners Pty Ltd (1992). Department of Health – s170 Register.

- State Projects Heritage Group (1995). Department of Corrective Service: Interim Heritage and Conservation Register.

- State Projects Heritage Group (1995). Department of Corrective Services: Interim Heritage and Conservation Register.

- Tanner Kibble Denton Architects Pty Ltd; UrbanGrowth NSW (17 March 2017). "Parramatta North Historic Sites Consolidated Conservation Management Plan: Part B—Norma Parker Centre/Kamballa Site" (PDF) – via UrbanGrowth NSW.

Attribution

This article incorporates text by Commonwealth of Australia available under the CC BY 3.0 AU licence.

This article incorporates text by Commonwealth of Australia available under the CC BY 3.0 AU licence. This Wikipedia article contains material from Cumberland District Hospital Group, entry number 00820 in the New South Wales State Heritage Register published by the State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) 2018 under CC-BY 4.0 licence, accessed on 2 June 2018.

This Wikipedia article contains material from Cumberland District Hospital Group, entry number 00820 in the New South Wales State Heritage Register published by the State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) 2018 under CC-BY 4.0 licence, accessed on 2 June 2018.

This Wikipedia article contains material from Norma Parker Correctional Centre, entry number 00811 in the New South Wales State Heritage Register published by the State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) 2018 under CC-BY 4.0 licence, accessed on 2 June 2018.

This Wikipedia article contains material from Norma Parker Correctional Centre, entry number 00811 in the New South Wales State Heritage Register published by the State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) 2018 under CC-BY 4.0 licence, accessed on 2 June 2018.

Further reading

- Hendriksen, Gay; Liston, Carol; Cowley, Trudy (2008). Women Transported – Life in Australia's Convict Female Factories. Parramatta: Parramatta Heritage Centre.