Paris during the Second Empire

During the Second French Empire, the reign of Emperor Napoleon III (1852–1870), Paris was the largest city in continental Europe and a leading center of finance, commerce, fashion, and the arts. The population of the city grew dramatically, from about one million to two million persons, partly because the city was greatly enlarged, to its present boundaries, through the annexation of eleven surrounding communes and the subsequent creation of eight new arrondissements.

.jpg.webp)

| History of Paris |

|---|

|

| See also |

|

|

In 1853, Napoleon III and his prefect of the Seine, Georges-Eugène Haussmann, began a massive public works project, constructing new boulevards and parks, theaters, markets and monuments, a project that Napoleon III supported for seventeen years until his downfall in 1870, and which was continued afterward under the Third Republic. The street plan and architectural style of Napoleon III and Haussmann are still largely preserved and manifestly evident in the center of Paris.

The Paris of Napoleon III

Napoleon III, the nephew of Napoleon Bonaparte, was born in Paris, but spent very little of his life there until he assumed the presidency of the French Second Republic in 1848. Earlier, he had lived most of his life in exile in Switzerland, Italy, the United States, and England. At the time of his election as the French president, he had to ask Victor Hugo where the Place des Vosges was located. He was greatly influenced by London, where he had spent years in exile; he admired its squares, wide streets, sidewalks, and especially Hyde Park with its lake and winding paths, which he later copied in the Bois de Boulogne and other Paris parks.

In 1852, Paris had many beautiful buildings; but, according to many visitors, it was not a beautiful city. The most significant civic structures, such as the Hôtel de Ville and the Cathedral of Notre Dame, were surrounded and partially hidden by slums. Napoleon wanted to make them visible and accessible.[1] Napoleon III was fond of quoting the utopian philosopher Charles Fourier: "A century which does not know how to provide luxurious buildings can make no progress in the framework of social well-being... A barbarian city is one composed of buildings thrown together by hazard, without any evident plan, and grouped in confusion between twisting, narrow, badly-made and unhealthy streets." In 1850, he declared: "Let us make every effort to embellish this great city. Let us open new streets, make healthy the crowded arrondissements which are lacking air and daylight, and let the healthy sunlight penetrate every corner within our walls."[2]

When Napoleon III staged a coup d'état to become Emperor in December 1852, he began to transform Paris into a more open, healthier, and more beautiful city. He immediately attacked the major flaws of the city: overcrowded and unhealthy slums, particularly on the Ile de la Cité; the shortage of drinking water; sewers that emptied directly into the Seine; the absence of parks and green spaces, especially in the outer parts of the city; congestion in the narrow streets; and the need for easier travel between the new train stations.

Haussmann's renovation of Paris

In 1853, Napoleon III assigned his new prefect of the Seine department, Georges-Eugène Haussmann, the task of bringing more water, air, and light into the city center, widening the streets to make traffic circulation easier, and making it the most beautiful city in Europe.

Haussmann worked on his vast projects for seventeen years, employing tens of thousands of workers. He rebuilt the sewers of Paris so they no longer emptied into the Seine and built a new aqueduct and reservoir to bring in more fresh water. He demolished most of the old medieval buildings on the Île de la Cité and replaced them with a new hospital and government buildings.

In the city center, he conceived four avenues arranged as a huge cross: a north–south axis connecting the Gare de Paris-Est in the north with the Paris Observatory in the south, and an east–west axis from the Place de la Concorde along the Rue de Rivoli to the Rue Saint-Antoine. He built new, wide avenues, including the Boulevard Saint-Germain, the Avenue de l'Opéra, Avenue Foch (originally Avenue de l'impératrice), Avenue Voltaire, the Boulevard de Sébastopol and Avenue Haussmann. He planted more than one hundred thousand trees along the new avenues. Where they intersected, he built new squares, fountains, and parks, to give a more harmonious appearance to the city. He imposed strict architectural standards for the buildings along the new boulevards: they all had to be the same height, follow a similar design, and be faced with the same cream-hued stone. This gave the Paris boulevards the distinctive appearance they retain to the present day.[3]

For the recreation and relaxation of all classes of Parisians, Napoleon III created four new parks at the cardinal points of the compass: the Bois de Boulogne to the west, the Bois de Vincennes to the east, the Parc des Buttes-Chaumont to the north, and Parc Montsouris to the south.[4]

To better connect his capital with the rest of France, and to serve as the grand gateways to the city, Napoleon III built two new train stations, the Gare du Nord and the Gare d'Austerlitz, and rebuilt the Gare de Paris-Est and the Gare de Lyon. To revitalize the cultural life of the city, he demolished the old theater district, the "Boulevard du Crime", replaced it with five new theaters, and commissioned a new opera house, the Palais Garnier, as the new home of the Paris Opera, and the centerpiece of his downtown reconstruction. He also completed the Louvre, left unfinished since the French Revolution, built a new central market of gigantic glass and iron pavilions at Les Halles, and constructed new markets in each of the arrondissements.[5]

Paris expands – the annexation of 1860

In 1859, Napoleon III issued a decree annexing the suburban communes around Paris: La Villette, Belleville, Montmartre, Vaugirard, Grenelle, Auteuil, Passy, Batignolles, La Chapelle, Charonne, Bercy, and parts of Neuilly, Clichy, Saint-Ouen, Aubervilliers, Pantin, Le Pré-Saint-Gervais, Saint-Mandé, Bagnolet, Ivry-sur-Seine, Gentilly, Montrouge, Vanves, and Issy-les-Molineaux. All of them became part of the city of Paris in January 1860. Their residents were not consulted and were not entirely pleased, since it meant having to pay higher taxes; but there was no legal recourse available to them. The area of the city expanded to its present boundaries and jumped in population from 1,200,000 to 1,600,000. The annexed areas were organized into eight new arrondissements; Haussmann enlarged his plans for Paris to include new city halls, parks and boulevards to connect the new arrondissements to the center of the city.[6]

The population of Paris during the Second Empire

The population of Paris was recorded as 949,000 in 1851. It grew to 1,130,500 by 1856 and was just short of two million by the end of Second Empire, including the 400,000 residents of the suburbs annexed to Paris in 1860.[7] According to a census made by the city of Paris in 1865, Parisians lived in 637,369 apartments or residences. Forty-two percent of the city population, or 780,000 Parisians, were classified as indigent, and thus too poor to be taxed. Another 330,000 Parisians, who occupied 17 percent of the housing of the city, were classified as lower middle class, defined as individuals who paid rents of less than 250 francs. 32 percent of the lodgings in Paris were occupied by the upper-middle class, defined as individuals who paid rents of between 250 and 1500 francs. Three percent of Parisians, or fifty thousand people, were classified as wealthy individuals who paid more than 1500 francs for rent.[8]

Artisans and workers

In the early part of the 19th century, the majority of Parisians were employed in commerce and small shops; but by the mid-19th century, conditions had changed. In 1864, 900,000 of the 1,700,000 inhabitants of Paris were employed in workshops and industry. These workers were typically employed in manufacturing, usually for the luxury market and on a small scale. The average atelier, or workshop, employed only one or two workers.[9] Similar types of manufacturing tended to be located in particular areas of the city. Furniture-makers and craftsmen who worked with bronze were located in the Faubourg Saint-Antoine; makers of tassels were found in the Faubourg Saint-Denis; shops that specialized in fabric trimming and fringes (passementerie) were found (and are still found) in the Temple area. Often the workshops were found in old houses on side streets. Thousands of crafts worked at home, making everything from watch chains to shoes and clothing. A large garment business could employ four thousand men and women, most working at home. In the Temple area, twenty-five thousand workers worked for five thousand employers.[10]

The market for Parisian products changed during the Second Empire. Previously, the clientele for luxury goods had been very small, mostly restricted to the nobility; and to meet their needs a small number of craftsmen had worked slowly and to very high standards. During the Second Empire, with the growth of the number of wealthy and upper middle class clients, lower-paid specialist craftsmen began to make products in greater quantity and more quickly, but of poorer quality than before. Craftsmen with nineteen different specialties were employed to make high-quality Moroccan leather goods. To make fine dolls, separate craftsmen and women, working separately and usually at home, made the body, the head, the arms, the teeth, the eyes, the hair, the lingerie, the dresses, the gloves, the shoes, and the hats.[11]

Between 1830 and 1850, more heavy industry began to locate in Paris. One tenth of all the steam engines in France were made in the capital. These industrial enterprises were usually located in the outer parts of the city, where there was land and access to the rivers or canals needed to move heavy goods. The metallurgy industry established itself along the Seine in the eastern part of the city. The chemical industry was located near La Villette, in the outer part of the city, or at Grenelle. Factories were established to make matches, candles, rubber, ink, gelatine, glue, and various acids. A thousand workers were employed by the Gouin factory in Batignolles to make steam engines. Fifteen hundred were employed by the Cail factories in Grenelle and Chaillot to make rails and ironwork for bridges. At Levallois-Perret, a young engineer, Gustave Eiffel, started an enterprise to make the frames of iron buildings. The eastern part of the city was subjected to noise, smoke, and the smells of industry. Wealthier Parisians moved to the west end of the city, which was quieter and where the prevailing winds kept out the smoke from the east. When the wealthy and middle-class people deserted the eastern areas, most of the small shops also closed and relocated elsewhere, leaving the outer suburbs of eastern Paris with only factories, and housing occupied by the poor.[12]

Wages and working hours

The artisans and workers of Paris had a precarious existence. 73% of the residents of the working-class areas earned a daily salary between 3.25 and 6 francs; 22% earned less than three francs; only 5% had a salary between 6.5 and 20 francs. Food cost a minimum of one franc a day, and the minimum necessary for lodging was 75 centimes a day. In most industries, except those connected with food, there was a long morte-saison ("dead season"), when the enterprises closed down and their workers were unpaid. To support a family properly, either the wife and children had to work, or the husband had to work on Sundays or longer hours than normal. The situation for women was even worse; the average salary for a woman was only two francs a day. Women workers also faced increasing competition from machines: two thousand sewing machines, just coming into use, could replace twelve thousand women sewing by hand. Women were typically laid off from work before men.[13]

The workday at three-quarters of the enterprises in Paris was twelve hours, with two hours allowed for lunch. Most workers lived far from their place of employment, and public transport was expensive. A train on the Petite Ceinture line cost 75 centimes round-trip, so most workers walked to work with a half-kilogram loaf of bread for their lunch. Construction workers on Haussmann's grand projects in the city center had to leave home at 4 a.m. to arrive at work by 6 a.m., when their workday began. Taverns and wine merchants near the work sites were open at a very early hour; it was common for workers to stop for a glass of white wine before work to counter the effects of what they had drunk the night before.

Office workers were not paid much better than artisans or industrial workers. The first job of novelist Émile Zola, in May 1862, was working as a mail clerk for the book publisher Louis Hachette; he put books into packets and mailed them to customers, for which he was paid 100 francs a month. In 1864, he was promoted to head of publicity for the publisher at a salary of 200 francs a month.[14]

The chiffonniers of Paris

The chiffonniers (sometimes translated "rag-pickers" in English) were the lowest class of Paris workers; they sifted through trash and garbage on the Paris streets for anything that could be salvaged. They numbered about twelve thousand at the end of the Second Empire. Before the arrival of the poubelle, or rubbish bin, during the Third Republic, trash and garbage were simply dumped onto the street. The lowest level of chiffoniers searched through the common refuse; they had to work very quickly, because there was great competition, and they feared that their competitors would find the best objects first. The placier was a higher class of chiffonier, who took trash from the houses of the upper classes, usually by arrangement with the concierge. The placier provided certain services, such as beating carpets or cleaning doorways, and in exchange was able to get more valuable items, from silk and satin to old clothing and shoes to leftovers from banquets. Six houses on the Champs-Elysees were enough to provide for the family of a placier. The next level up was the chineur, a merchant who bought and resold trash, such as old bottles and corks from taverns, old clothes and bits of iron. At the top of the hierarchy were the maître-chiffoniers, who had large sheds where trash was sorted and then resold. Almost everything was re-used: old corks were sold to wine-merchants; orange peels were sold to distillers; bones were used to make dominoes, buttons, and knife handles; cigar butts were resold; and stale bread was burned and used to make a cheap coffee substitute. Human hair was collected, carefully sorted by colour, length, and texture, and used to make wigs and hair extensions.[15]

The poor and indigent

Twenty-two percent of Parisians earned less than three francs a day, and daily life was a struggle for them. Their numbers grew as new immigrants arrived from other regions of France. Many came to the city early in the Empire to perform the unskilled work needed in demolishing buildings and moving earth for the new boulevards. When that work ended, few of the new immigrants left. The city established bureaux de bienfaisance—or charity bureaus, with an office in each arrondissement—to provide temporary assistance, usually in the form of food, to the unemployed, the sick, the injured, and women who were pregnant. The assistance ended when the recipients recovered; the average payment was 50 francs per family per year. Those who were old or had incurable illnesses were sent to a hospice. 130,000 people received this assistance, three-quarters of them immigrants from outside Paris. The public aid was supplemented by private charities, mostly operated by the church, which established a system of crèches for poor children and weekly visits by nuns to the homes of the sick and new mothers.[16]

For those working-class Parisians who had been laid off or were temporarily in need of money, a special institution existed: the Mont-de-Piété. Founded in 1777, it was a sort of pawn shop or bank for the poor, with a main office on the Rue des Francs-Bourgeois and bureaus in twenty arrondissements. The poor could bring any piece of property, from jewels or watches to old sheets, mattresses, and clothing, and receive a loan. In 1869, it received more than 1,500,000 deposits in exchange for loans, two-thirds of which were of less than ten francs. The interest rate on the loans was 9.5 percent, and any object not claimed within a year was sold. The institution collected between 1000 and 1200 watches a day. Many clients used the same watch or object to borrow money every month, when money ran short. Workers would often pawn their tools during a slow season without work.

Below the poor, there was an even lower class, of beggars and vagabonds. A law passed in 1863 made it a crime to be completely without money; those without any money at could be taken to jail, and those unlikely to get any money were taken to the Dépôt de mendicité, or beggar's depot, located in Saint-Denis, where about a thousand beggars were put to work making rope or straps, or sorting rags. They were paid a small amount, and when they had earned a certain sum, they were allowed to leave, but most soon returned; and the majority died at the depot.[17]

The morgue

The Paris morgue was located on the Quai de l'Archevêché on the Île de la Cité, not far from the Cathedral of Notre-Dame-de-Paris. In order to assist with the identification of unclaimed bodies, it was open to the public. Bodies fished out of the Seine were put on display behind a large glass window, along with the clothes that they had been wearing. A doctor working at the morgue wrote, "A multitude of the curious, of all ages, sexes, and social rank, presses in every day, sometimes moved and silent, often stirred by horror and disgust, sometimes cynical and turbulent."[18] On 28 June 1867 a body found without a head, arms or legs was put on display. The head, arms and legs were found a few days later, the body was identified, and the murderer tracked down and arrested. The system was macabre but effective; seventy-five percent of the bodies found in the Seine were identified in this way.[19]

The cemeteries

During the Second Empire, Paris had five main cemeteries: Père Lachaise, Montparnasse, Montmartre, Saint-Ouen, and Ivry-sur-Seine. In addition, there were several smaller communal cemeteries. Funeral parlors offered seven different styles of burial, ranging in price from 18 francs to more than 7,000 francs for an elaborate individual monument. Two thirds of Parisians, however, were buried in collective graves in a corner of the cemeteries, with the cost paid by the city. Before Napoleon III, the corpses of indigents were simply piled into trenches in seven layers, each covered with a thin layer of earth and lime. Napoleon III had the process made somewhat more dignified, with the corpses laid side by side in a single layer in a trench. The city would pay for a priest who, if requested, would provide a short service and scatter holy water on the trench. Indigents who died in hospitals and those whose bodies had been dissected in medical schools continued to be buried in the more crowded trenches. For all indigent burials, the bodies remained in the trenches only long enough for them to decompose, no longer than five years. After that time, all remains were dug up and transferred to an ossuary, so that the space could be used for new burials.[20]

In 1860, Haussmann complained that the cemeteries inside the city posed a serious threat to public health, and proposed to ban burials in the city. His alternative was to have all burials take place in a very large new cemetery, outside the city, served by special funeral trains that would bring the remains and the mourners from the city. Haussmann quietly began acquiring land for the new cemetery. The project ran into strong opposition in the French Senate in 1867, however, and Napoleon decided to postpone it indefinitely.[21]

Public transport

Railroads and stations

In 1863, Paris had eight passenger train stations that were run by eight different companies, each with rail lines connecting to a particular part of the country: the Gare du Nord connected Paris to Great Britain via ferry; the Gare de Strasbourg—now the Gare de l'Est—to Strasbourg, Germany, and eastern Europe; the Gare de Lyon—run by the Company Paris-Lyon-Mediterranée—to Lyon and the south of France; the Gare d'Orleans—now the Gare d'Austerlitz—to Bordeaux and southwest France; the Gare d'Orsay; the Gare de Vincennes; the Gare de l'Ouest Rive Gauche—on the Left Bank where the Gare Montparnasse is today—to Brittany, Normandy, and western France; and the Gare de l'Ouest—on the Right Bank, where the Gare Saint-Lazare is today—also connecting to the west. In addition, there was a huge station just outside the fortifications of the city where all freight and merchandise arrived.[22]

The owners and builders of the railroad stations competed to make their stations the most palatial and magnificent. The owner of the Gare du Nord, James Mayer de Rothschild, stated that arriving at his station would have "an imposing effect, due to the grandeur of the station."[23] He completely demolished the old station and hired Jacques Hittorff, a classical architect who had designed the Place de la Concorde, to create the new station. The monumental facade included twenty-three statues by famous sculptors, representing the cities of northern France served by the company. At its opening in 1866, it was described as "a veritable temple of steam."[24]

The Gare de l'Ouest, on the right bank, the busiest of the stations, occupied eleven hectares and was home to a fleet of 630 locomotives and 13,686 passenger coaches, including those for first class, second class, and third class. 70 trains a day operated in the peak season and during the Paris expositions. If passengers needed to make a connection, a service of 350 horse-drawn omnibuses operated by the railroad carried passengers to the other stations.

The journey from Paris to Orléans, a distance of 121 kilometers, cost 13 francs 55 centimes for a first-class ticket; 10 francs 15 centimes for a second class ticket; and 7 francs 45 centimes for a 3rd class ticket.[25]

The engineers or drivers of the locomotives, called mechaniciens, had a particularly difficult job; the cabs of the locomotives had no roofs and no sides, and were exposed to rain, hail, and snow. In addition, it was scorching hot, since they had to work in front of the boiler. A locomotive driver earned 10 francs a day.[26]

The new train stations welcomed millions of tourists, including those who came for the two Universal Expositions during the Second Empire. They also welcomed hundreds of thousands of immigrants from other parts of France who came to work and settle in Paris. Immigrants from different regions tended to settle in areas close to the station that served their old region: Alsatians tended to settle around the Gare de l'Est and Bretons around the Gare de l'Ouest, a pattern still found today.

The omnibus and the fiacre

From 1828 to 1855, Parisian public transport was provided by private companies that operated large horse-drawn wagons with seats, a vehicle called an omnibus. The omnibuses of each company had distinct liveries and picturesque names: the Favorites, the Dames Blanches, the Gazelles, the Hirondelles, the Citadines. They served only the city center and wealthier areas, ignoring the working-class areas and the outer suburbs of the city. In 1855, Napoleon III's prefect of police, Pierre-Marie Piétri, required the individual companies to merge under the name Compagnie général de omnibus. This new company had the exclusive rights to provide public transport. It established 25 lines that expanded to 31 with the annexation of the outer suburbs, about 150 kilometers in total length. A ticket cost 30 centimes and entitled the passenger to one transfer. In 1855, the company had 347 cars and carried 36 million passengers. By 1865, the number of cars had doubled and the number of passengers had tripled.[27]

The Paris omnibus was painted in yellow, green, or brown. It carried fourteen passengers on two long benches and was entered from the rear. It was pulled by two horses and was equipped with a driver and conductor dressed in royal blue uniforms with silver-plated buttons, decorated with the gothic letter O, and with a black necktie. The conductor wore a kepi and the driver a hat of varnished leather. In summer, they wore blue and white striped trousers and black straw hats. The omnibus was required to stop any time a passenger wanted to get on or off, but with time, the omnibus became so popular that passengers had to wait in line to get a seat.

The other means of public transport was the fiacre, a box-like coach drawn by one horse that could hold as many as four passengers, plus the driver, who rode on the exterior. In 1855, the many different enterprises that operated fiacres were merged into a single company, the Compagnie impériale des voitures de Paris. In 1855, the company had a fleet of 6,101 fiacres with the emblem of the company on the door, and the drivers wore uniforms. The fiacres carried lanterns that indicated the area in which their depot was located: blue for Belleville, Buttes-Chaumont, and Popincourt; yellow for Rochechouart and the Pigalle; green for the Left Bank; red for Batignolles, Les Ternes, and Passy. The color of the lantern allowed customers leaving the theaters to know which fiacres would take them to their own area. The fare was 1.80 francs for a journey, or 2.50 francs for an hour. A wait of more than five minutes allowed the driver to demand payment for a full hour. The drivers were paid 1.5 francs per day for a working day that could last 15 to 16 hours. The company maintained a special service of plain-clothes agents to keep an eye on the drivers and make certain they submitted all the money they had collected. The fiacre was enclosed and upholstered inside with dark blue cloth. Fiacres figured prominently in the novels and poetry of the period; they were often used by clandestine lovers.[28]

Gas lamps and the City of Light

The gas lights that illuminated Paris at night during the Second Empire were often admired by foreign visitors and helped revive the city nickname Ville-Lumiére, the City of Light. At the beginning of the Empire, there were 8,000 gas lights in the city; by 1870, there were 56,573 used exclusively to light the city streets.[29]

The gas was produced by ten enormous factories—located around the edge of the city, near the circle of fortifications—and was distributed in pipes installed under the new boulevards and streets. Haussmann placed street lamps every twenty meters on the boulevards. Shortly after nightfall, a small army of 750 allumeurs in uniform, carrying long poles with small lamps at the end, went out into the streets, turned on a pipe of gas inside each lamppost, and lit the lamp. The entire city was illuminated within forty minutes. The amount of light was greatly enhanced by the white stone walls of the new Haussmann apartment buildings, which reflected the brilliant gaslight. Certain buildings and monuments were also illuminated: the Arc de Triomphe was crowned with a ring of gaslights, and they outlined the Hôtel de Ville. The Champs-Elysees was lined with ribbons of white light. The major theaters, cafés, and department stores were also brightly lit with gaslight, as were some rooms in apartments in the new Haussmann buildings. The concert gardens, in which balls were held in summer, had gas lighting, as well as small gas lamps in the gardens, where gentlemen could light their cigars and cigarettes.[30]

The central market – Les Halles

The central market of Paris, Les Halles, had been in the same location on the Right Bank between the Louvre and the Hôtel de Ville since it was established by King Philippe-Auguste in 1183. The first market had walls and gates, but no covering other than tents and umbrellas. It sold food, clothing, weapons, and a wide range of merchandise. By the middle of the 19th century, the open-air market was overcrowded, unsanitary, and inadequate for the needs of the growing city. On 25 September 1851 Napoleon III, then Prince-President, placed the first stone for a new market. The first building looked like a grim medieval fortress and was criticised by the merchants, public, and the Prince-President himself. He stopped construction and commissioned a different architect, Victor Baltard, to come up with a better design. Baltard took his inspiration from The Crystal Palace in London, a revolutionary glass-and-cast-iron structure that had been built in 1851. Baltard's new design had fourteen enormous pavilions with glass and cast-iron roofs resting on brick walls. It covered an area of 70 hectares and cost 60 million francs to build. By 1870, ten of the fourteen pavilions were finished and in use. Les Halles was the major architectural achievement of the Second Empire and became the model for covered markets around the world.[31]

Each night, 6000 wagons converged on Les Halles, carrying meat, seafood, produce, milk, eggs, and other food products from the train stations. The wagons were unloaded by 481 men wearing large hats called les forts (the strong), who carried the food in baskets to the pavilions. Pavilion no. 3 was the hall for meat; no. 9 for seafood; no. 11 for birds and game. Merchants in the pavilions rented their stalls for between one and three francs a day. Fruits and vegetables also arrived at night, brought by carts from farms and gardens around Paris; the farmers rented small spaces of one by two meters on the sidewalk outside the pavilions to sell their produce. The meat was carved, the produce put out on the counters, and the sellers—called "counter criers"—were in place by 5 a.m., when the market opened.

The first buyers in the morning were from institutions: soldiers with large sacks buying food for the army barracks; cooks buying for colleges, monasteries, and other institutions; and owners of small restaurants. Between six and seven in the morning, the fresh seafood arrived from the train stations, mostly from Normandy or Brittany, but some from England and Belgium. The fish were cleaned and put on the eight counters in hall no. 9. They were carefully arranged by sixteen verseurs ("pourers" or "spillers") and advertised in loud voices by 34 counter criers. As soon as the fish appeared, it was sold.

From 1 September until 30 April, oysters were sold in pavilion no. 12 for ten centimes each, which was too expensive for most Parisians. The oysters were shipped from Les Halles to customers as far away as Moscow and Saint Petersburg. Butter, cheese, and eggs were sold in pavilion no. 10, the eggs having arrived in large packages containing a thousand eggs each. The butter and milk was checked and tasted by inspectors to make sure it matched advertised quality, and 65 inspectors verified the size and quality of the eggs.

Pavilion no. 4 sold live birds: chickens, pigeons, ducks, and pheasants, as well as rabbits and lambs. It was by far the noisiest and the worst-smelling pavilion, because of the live animals; and it had a special ventilating system. No. 8 sold vegetables, and no. 7 sold fresh flowers. No. 12 had bakers and fruit sellers, and also sold what were known as rogations; these were leftovers from restaurants, hotels, the Palace, and government ministries. The leftovers were sorted and put on plates; and any that looked acceptable were sold. Some leftovers were reserved for pet foods; old bones were collected to make bouillon; uneaten bread crusts from schools and restaurants were used to make croutons for soup and bread-coating for cutlets. Many workers in Les Halles got their meals at this pavilion.

Cooks from good restaurants arrived in the mid-morning to buy meat and produce, parking fiacres in rows in front of the Church of Saint-Eustache. Most of the food was sold by 10 a.m.; seafood remained on sale until noon. The rest of the day was used for recording orders, and for resting until whatever market opened again late that night.[32]

Cafés and restaurants

The Café Tortoni, famous for its ice cream, on the Boulevard des Italiens (1856)

The Café Tortoni, famous for its ice cream, on the Boulevard des Italiens (1856) The Maison Dorée in about 1860.

The Maison Dorée in about 1860. The Café Riche on the Boulevard des Italiens in about 1865

The Café Riche on the Boulevard des Italiens in about 1865

Thanks to the growing number of wealthy Parisians and tourists coming to the city and the new network of railroads that delivered fresh seafood, meat, vegetables, and fruit to Les Halles every morning, Paris during the Second Empire had some of the best restaurants in the world. The greatest concentration of top-class restaurants was on the Boulevard des Italiens, near the theaters. The most prominent of these at the beginning the Empire was the Café de Paris, opened in 1826, which was located on the ground floor of the Hôtel de Brancas. It was decorated in the style of a grand apartment, with high ceilings, large mirrors, and elegant furniture. The director of the Paris Opéra had a table reserved for him there, and it was a frequent meeting place for characters in the novels of Balzac. It was unable to adapt to the style of the Second Empire, however; it closed too early, at ten in the evening, the hour when the new wealthy class of Second Empire Parisians were just going out to dinner after the theatre or a ball. As a result, it went out of business in 1856.[33]

The most famous newer restaurants on the Boulevard des Italiens were the Maison Dorée, the Café Riche, and the Café Anglais, the latter two of which faced each other across the boulevard. They, and the other cafés modelled after them, had similar interior arrangements. Inside the door, the clients were welcomed by the dame de comptoir, always a beautiful woman who was very elegantly dressed. Besides welcoming the clients, she was in charge of the distribution of pieces of sugar, two for each demitasse of coffee. A demitasse of coffee cost between 35 and 40 centimes, to which clients usually added a tip of two sous, or ten centimes. An extra piece of sugar cost ten centimes. The floor of the café was lightly covered with sand, so the hurrying waiters would not slip. The technology of the coffee service was greatly improved in 1855 with the invention of the hydrostatic coffee percolator, first presented at the Paris Universal Exposition of 1855, which allowed a café to produce 50,000 demitasses a day.[34]

The Maison Dorée was decorated in an extravagant Moorish style, with white walls and gilded furnishings, balconies and statues. It had six dining salons and 26 small private rooms. The private dining rooms were elegantly furnished with large sofas as well as tables and were a popular place for clandestine romances. They also featured large mirrors, where women had the tradition of scratching messages with their diamond rings. It was a popular meeting place between high society and what was known as the demimonde of actresses and courtesans; it was a favorite dining place of Nana in the novel of that name by Émile Zola.[35]

The Café Riche, located at the corner of the Rue Le Peletier and the Boulevard des Italiens, was richly decorated by its owner, Louis Bignon, with a marble and bronze stairway, statues, tapestries, and velour curtains. It was the meeting place of bankers, actors, actresses, and successful painters, journalists, novelists, and musicians. The upstairs rooms were the meeting places of the main characters in Émile Zola's novel La Curée.

The Café Anglais, across the street from the Café Riche, had a famous chef, Adolphe Dugléré, whom the composer Gioachino Rossini, a frequent customer, described as "the Mozart of French cooking". The café was also famous for its cave containing two hundred thousand bottles of wine. The café occupied the ground floor; on the first floor there were twelve small private dining rooms and four larger dining salons decorated in white and gold. The largest and most famous was the Grand Seize, or "Grand Sixteen", where the most famous bankers, actors, actresses, aristocrats, and celebrities dined. In 1867, the "Grand Seize" was the setting for the Three Emperors Dinner, a sixteen-course dinner with eight wines consumed by Kaiser Wilhelm I of Germany, Czar Alexander II of Russia, his son the future Czar Alexander III of Russia, and the Prussian chancellor Otto von Bismarck.

The Boulevard des Italiens also featured the Café Foy, at the corner of the Rue de la Chaussée-d'Antin, and the Café Helder, a popular rendezvous for army officers. The cafés on the boulevard opened onto terraces, which were used in good weather. The Café Tortoni, at 22 Boulevard des Italiens, which had been in place since the 1830-1848 reign of Louis-Philippe, was famous for its ice cream. On summer days, carriages lined up outside on the boulevard as wealthy Parisians sent their servants into Tortoni to buy ice cream, which they consumed in their carriages. It was also a popular place to go after the theatre. Its regular clients included Gustave Flaubert and Édouard Manet.[36]

Just below the constellation of top restaurants, there were a dozen others that offered excellent food at less extravagant prices, including the historic Ledoyen, next to the Champs-Elysées, where the famous painters had a table during the Salon; others listed in a guidebook for foreign tourists were the cafés Brébant, Magny, Veron, Procope and Durand.[37] According to Émile Zola, a full-course dinner in such a restaurant cost about 25 francs.[38]

According to Eugene Chavette, author of an 1867 restaurant guide, there were 812 restaurants in Paris, 1,664 cafés, 3,523 debits de vin, 257 crémeries, and 207 tables d'hôtes.[39] The latter were inexpensive eating places, often with a common table, where a meal could be had for 1.6 francs, with a bowl of soup, a choice of one of three main dishes, a dessert, bread, and a half-bottle of wine. As a guidebook for foreign visitors noted, "A few of these restaurants are truly good; many others are bad." Ingredients were typically of poor quality. The soup was a thin broth of bouillon; as each spoonful of soup was taken from the pot, an equal amount of water was usually added, so the broth became thinner and thinner.[40]

Bread and wine

Bread was the basic diet of the Parisian workers. There was one bakery for every 1349 Parisians in 1867, up from one bakery for every 1800 in 1853. However, the per capita daily consumption of bread of Parisians dropped during the Second Empire, from 500 grams per day per person in 1851 to 415 grams in 1873. To avoid popular unrest, the price of bread was regulated by the government and fixed at about 50 centimes per kilo. The fast-baked baguette was not introduced until 1920, so bakers had to work all night to bake the bread for the next day. In order to make a profit, bakers created a wide variety of what were known as "fantasy" breads, made with better quality flours and with different grains; the price of these breads ranged from 80 centimes to a franc per kilo.[41]

The consumption of wine by Parisians increased during the Second Empire, while the quality decreased. It was unusual for women to drink; but, for both the workers and the middle and upper classes, wine was part of the daily meal. The number of debits de boissons, bars where wine was sold, doubled. Ordinary wine was produced by mixing several different wines of different qualities from different places in a cask and shaking it. The wine sold as ordinary Mâcon was made by mixing wine from Beaujolais, Tavel, and Bergerac. The best wines were treated much more respectfully; in 1855, Napoleon III ordered the classification of Bordeaux wines by place of origin and quality, so that they could be displayed and sold at the Paris Universal Exposition.

Wine was bought and sold at the Halle aux Vins, a large market established by Napoleon I in 1811, but not finished until 1845. It was located on the Left Bank of the Seine, on the Quai Saint Bernard, near the present-day Jardin des Plantes. It was on the river so that barrels of wine could be delivered by barge from Burgundy and other wine regions, and unloaded directly into the depot. The hand-made barrels were enormous and were of slightly different sizes for each region; barrels of Burgundy wine held 271 liters each. The Halle aux Vins covered fourteen hectares, and contained 158 wine cellars at ground level. It sold not only wine, but also liquors, spirits, vinegar, and olive oil. Wine merchants rented space in the cellars and halls that were located in four large buildings. All the wine and spirits were taxed; inspectors in the halls opened all the barrels, tested the wine to be certain it did not contain more than 18 percent alcohol, and one of 28 tasters employed by the Prefecture de Police tasted each to verify that it was, in fact, wine. Wine that contained more than 18 percent alcohol was taxed at a higher rate. The Halle sold 956,910 hectoliters of wine to Parisian cafés, bars, and local wine merchants in 1867.[42]

Absinthe and tobacco

Absinthe had made its appearance in Paris in the 1840s, and it became extremely popular among the "Bohemians" of Paris: artists, writers, and their friends and followers. It was known as the "Goddess with green eyes," and was usually drunk with a small amount of sugar on the edge of the glass. The hour of 5 p.m. was called l'heure verte ("the green hour"), when the drinking usually began, and it continued until late at night.

Before the Second Empire, smoking had usually been limited to certain rooms or salons of restaurants or private homes, but during the Empire, it became popular to smoke on all occasions and in every location, from salons to the dining rooms of restaurants. Cigars imported from Havana were smoked by the Parisian upper class. To meet the growing demand for cigars, the government established two cigar factories in Paris. The one at Gros-Caillou was located on the banks of the Seine near the Palais d'Orsay; it was the place in which ordinary cigars were made, usually with tobacco from Virginia, Maryland, Kentucky, Mexico, Brazil, or Hungary. The cigars from Gros-Caillou sold for between 10 and 20 centimes each. Another factory, at Reuilly, made luxury cigars with tobacco imported directly from Havana; they sold for 25 to 50 centimes each. The Reuilly factory employed a thousand workers, of whom 939 were women, a type of work culture in the tobacco industry depicted in the opera Carmen (1875) by Georges Bizet. One woman worker could make between 90 and 150 cigars during a ten-hour workday.[43]

The novelty shop and the first department stores

The Second Empire saw a revolution in retail commerce, as the Paris middle class and consumer demand grew rapidly. The revolution was fuelled in large part by Paris fashions, especially the crinoline, which demanded enormous quantities of silk, satin, velour, cashmere, percale, mohair, ribbons, lace, and other fabrics and decorations. Before the Second Empire, clothing and luxury shops were small and catered to a very small clientele; their windows were covered with shutters or curtains. Any who entered had to explain their presence to the clerks, and prices were never posted; customers had to ask for them.

The first novelty stores, which carried a wide variety of goods, appeared in the late 1840s. They had larger, glass windows, made possible by the new use of cast iron in architecture. Customers were welcome to walk in and look around, and prices were posted on every item. These shops were relatively small, and catered only to a single area, since it was difficult for Parisians to get around the city through its narrow streets.

Innovation followed innovation. In 1850, the store named Le Grand Colbert introduced glass show windows from the pavement to the top of the ground floor. The store Au Coin de la Rue was built with several floors of retail space around a central courtyard that had a glass skylight for illumination, a model soon followed by other shops. In 1867, the store named La Ville Saint-Denis introduced the hydraulic elevator to retail.

The new Haussmann boulevards created space for new stores, and it became easier for customers to cross the city to shop. In a short time, the commerce in novelties, fabrics, and clothing began to be concentrated in a few very large department stores. Bon Marché was opened in 1852, in a modest building, by Aristide Boucicaut, the former chief of the Petit Thomas variety store. Boucicaut's new venture expanded rapidly, its income growing from 450,000 francs a year to 20 million. Boucicaut commissioned a new building with a glass and iron framework designed in part by Gustave Eiffel. It opened in 1869 and became the model for the modern department store. The Grand Magasin du Louvre opened in 1855 inside the vast luxury hotel built by the Péreire brothers next to the Louvre and the Place Royale. It was the first department store that concentrated on luxury goods, and tried both to provide bargains and be snobbish. Other department stores quickly appeared: Printemps in 1865, the Grand Bazar de l'Hôtel de Ville (BHV) in 1869, and La Samaritaine in 1870. They were soon imitated around the world.[44]

The new stores pioneered new methods of marketing, from holding annual sales to giving bouquets of violets to customers or boxes of chocolates to those who spent more than 25 francs. They offered a wide variety of products and prices: Bon Marché offered 54 kinds of crinolines, and 30 different kinds of silk. The Grand Magasin du Louvre sold shawls ranging in price from 30 francs to 600 francs.[45]

Painting during the Second Empire

"The Birth of Venus", by Alexandre Cabanel, was purchased by Napoleon III at the Paris Salon of 1863

"The Birth of Venus", by Alexandre Cabanel, was purchased by Napoleon III at the Paris Salon of 1863 "Napoleon I in 1814", a portrait of Napoleon III's uncle, by Jean-Louis-Ernest Meissonier.

"Napoleon I in 1814", a portrait of Napoleon III's uncle, by Jean-Louis-Ernest Meissonier. "The Death of Caesar" by Jean-Léon Gérôme, a highly successful academic history painter from the Second Empire.

"The Death of Caesar" by Jean-Léon Gérôme, a highly successful academic history painter from the Second Empire.

The Paris Salon

During the Second Empire, the Paris Salon was the most important event of the year for painters, engravers, and sculptors. It was held every two years until 1861, and every year thereafter, in the Palais de l'Industrie, a gigantic exhibit hall built for the Paris Universal Exposition of 1855. A medal from the Salon assured an artist of commissions from wealthy patrons or from the French government. Following rules of the Academy of Fine Arts established in the 18th century, a hierarchy of painting genres was followed: at the highest level was history painting, followed in order by portrait painting, landscape painting, and genre painting, with still-life painting at the bottom. Painters devoted great effort and intrigue to win approval from the jury to present their paintings at the Salon and arrange for good placement in the exhibition halls.

The Paris Salon was directed by the Count Émilien de Nieuwerkerke, the Superintendent of Fine Arts, who was known for his conservative tastes. He was scornful of the new school of Realist painters led by Gustave Courbet. One of the most successful Salon artists was Alexandre Cabanel, who produced a famous full-length portrait of Napoleon III, and a painting The Birth of Venus that was purchased by the Emperor at the Salon of 1863. Other successful academic painters of the Second Empire included Jean-Louis-Ernest Meissonier, Jean-Léon Gérôme, and William-Adolphe Bouguereau.[46]

Ingres, Delacroix, Corot

The Turkish Bath (1862) by Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres.

The Turkish Bath (1862) by Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres. The Abduction of Rebecca (1858) by Eugène Delacroix, the leader of the romantic school of painting.

The Abduction of Rebecca (1858) by Eugène Delacroix, the leader of the romantic school of painting. Saint Michael Defeats the Devil (1849-1861), in the Church of Saint-Sulpice, one of Delacroix's last major works.

Saint Michael Defeats the Devil (1849-1861), in the Church of Saint-Sulpice, one of Delacroix's last major works. A landscape (1860) by Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot. Corot achieved popular and critical success during the Second Empire after a long period of relative obscurity.

A landscape (1860) by Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot. Corot achieved popular and critical success during the Second Empire after a long period of relative obscurity.

The older generation of painters in Paris during the Second Empire was dominated by Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres (1780-1867), the most prominent figure for history and neoclassical painting; Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863), the leader of the romantic school of painting; and Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot (1796-1875), who was widely regarded as the greatest French landscape painter of the 19th century.[47]

Ingres had begun painting during the reign of Napoleon I, under the teaching of Jacques-Louis David. In 1853, during the reign of Napoleon III, he painted a monumental Apotheosis of Napoleon I on the ceiling of the Hotel de Ville of Paris, which was destroyed in May 1871 when the Communards burned the building. His work combined elements of neoclassicism, romanticism, and innocent eroticism. He painted his famed Turkish Bath in 1862, and he taught and inspired many of the academic painters of the Second Empire.

Delacroix, as the founder of the Romantic school, took French painting in a very different direction, driven by emotion and colour. His friend the poet Charles Baudelaire wrote, "Delacroix was passionately in love with passion, but coldly determined to express passion as clearly as possible". Delacroix decorated the Chapelle des Saints-Anges at the Church of Saint-Sulpice with his frescoes, which were among his last works.

Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot began his career with study at the École des Beaux-Arts as an academic painter, but gradually began painting more freely and expressing emotions and feelings through his landscapes. His motto was "never lose that first impression which we feel." He made sketches in the forests around Paris, then reworked them into final paintings in his studio. He was showing paintings in the Salon as early as 1827, but he did not achieve real fame and critical acclaim before 1855, during the Second Empire.[48]

Courbet and Manet

Gustave Courbet's painting of ordinary young women taking a nap by the Seine (1856) caused a scandal at the Paris Salon, much to the delight of the artist.

Gustave Courbet's painting of ordinary young women taking a nap by the Seine (1856) caused a scandal at the Paris Salon, much to the delight of the artist. Luncheon on the Grass by Édouard Manet caused a scandal at the Paris Salon of 1863 and helped make Manet famous.

Luncheon on the Grass by Édouard Manet caused a scandal at the Paris Salon of 1863 and helped make Manet famous.

Gustave Courbet (1819-1872) was the leader of the school of realist painters during the Second Empire who depicted the lives of ordinary people and rural life, as well as landscapes. He delighted in scandal and condemned the art establishment, the Academy of Fine Arts, and Napoleon III. In 1855, when his submissions to the Salon were rejected, he set up his own exhibit in a nearby building and displayed forty of his paintings there. In 1870, Napoleon III proposed giving the Legion of Honour to Courbet, but he publicly rejected it.

Édouard Manet was one of the first non-academic artists to achieve both popular and critical success during the Second Empire, thanks in part to a little help from Napoleon III. Manet's painting The Luncheon on the Grass (Le déjeuner sur l'herbe) was rejected by the jury of the 1863 Paris Salon, along with many other non-academic paintings by other painters. Napoleon III heard complaints about the rejection and directed the Academy of Fine Arts to hold a separate exhibit, known as the Salon des Refusés (Salon of the Rejected), in the same building as the Salon. The painting was criticized and ridiculed by critics but brought Manet's work to the attention of a vast Parisian public.

Pre-Impressionism

Claude Monet exhibited a portrait of his future wife Camille Doncieux at the Paris Salon of 1866 under the title Woman in a Green Dress.

Claude Monet exhibited a portrait of his future wife Camille Doncieux at the Paris Salon of 1866 under the title Woman in a Green Dress. La Grenouillére by Pierre-Auguste Renoir. Renoir studied art in Paris in 1862 and placed a painting in the Paris Salon of 1864.

La Grenouillére by Pierre-Auguste Renoir. Renoir studied art in Paris in 1862 and placed a painting in the Paris Salon of 1864.

A portrait of Manet and his wife by Edgar Degas. (1868–69)

A portrait of Manet and his wife by Edgar Degas. (1868–69)

While the official art world was dominated by the Salon painters, another lively art world existed in competition with and opposition to the salon. In an earlier period, this group included the painters Gustave Courbet, Édouard Manet, Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, and Alfred Sisley; then, later, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Frédéric Bazille, and Henri Fantin-Latour. Their frequent meeting place was the Café Guerbois at 11 Avenue de Clichy.[49] The café was close to the foot of Montmartre, where many of the artists had their studios. The artists interested in the new popularity of Japanese prints frequented the gallery of Édouard Desoye or the Léger gallery on the Rue le Peletier. The painters also frequented the galleries that exhibited the new style of art, such as those of Paul Durand-Ruel, Ambroise Vollard, and Alexandre Bernheim on the Rue Laffitte and Rue le Peletier, or the gallery of Adolphe Goupil on the Boulevard Montmartre, where Théo van Gogh, the brother of Vincent van Gogh, worked. The paintings of Manet could be seen at the gallery of Louis Martinet at 25 Boulevard des Italiens.

The term "Impressionist" was not invented until 1874; but during the Second Empire, all the major impressionist painters were at work in Paris, inventing their own personal styles. Claude Monet exhibited two of his paintings, a landscape and a portrait of his future wife Camille Doncieux, at the Paris Salon of 1866.

Edgar Degas (1834-1917), the son of a banker, studied academic art at the École des Beaux-Arts and travelled to Italy to study the Renaissance painters. In 1868, he began to frequent the Café Guerbois, where he met Manet, Monet, Renoir, and the other artists of a new, more natural school, and began to develop his own style.[50]

Literature

Victor Hugo lived in exile on the island of Jersey during almost all of the period of the Second Empire, but his works, including Les Miserables of 1862, were immensely popular in Paris.

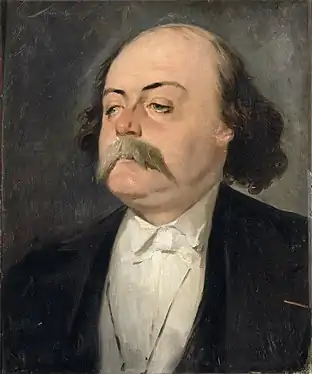

Victor Hugo lived in exile on the island of Jersey during almost all of the period of the Second Empire, but his works, including Les Miserables of 1862, were immensely popular in Paris. Gustave Flaubert published his novel Madame Bovary in 1866 and was charged with immorality for its content. He was acquitted, and the publicity made the novel a huge public success.

Gustave Flaubert published his novel Madame Bovary in 1866 and was charged with immorality for its content. He was acquitted, and the publicity made the novel a huge public success. Émile Zola began his literary career as a shipping clerk for the Paris publisher Hachette. He published his first major novel, Thérèse Raquin, in 1867.

Émile Zola began his literary career as a shipping clerk for the Paris publisher Hachette. He published his first major novel, Thérèse Raquin, in 1867. Charles Baudelaire also faced charges of immorality, in his case for his poetry. He was fined, and six of his poems were suppressed.

Charles Baudelaire also faced charges of immorality, in his case for his poetry. He was fined, and six of his poems were suppressed. Jules Verne worked at the Théâtre Lyrique and the Paris stock market and did research for his first stories at the National Library.

Jules Verne worked at the Théâtre Lyrique and the Paris stock market and did research for his first stories at the National Library.

The most famous Paris writer of the Second Empire, Victor Hugo, spent only a few days in the city during the entire period of the Second Empire. He was exiled shortly after Napoleon III seized power in 1852, and he did not return until after Napoleon's fall in 1870. The emperor stated publicly that Hugo could return whenever he wanted; but Hugo refused as a matter of principle, and while in exile wrote books and articles ridiculing and denouncing Napoleon III. His novel Les Misérables was published in Paris in April and May 1862 and was a huge popular success, though it was criticized by Gustave Flaubert, who said he found "no truth or greatness in it".[51]

Alexandre Dumas (1802-1870) left Paris in 1851, just before the Second Empire was proclaimed, partly because of political differences with Napoleon III, but largely because he was deeply in debt and wanted to avoid creditors. After travelling to Belgium, Italy, and Russia, he returned to Paris in 1864 and wrote his last major work, The Knight of Sainte-Hermine, before he died in 1870.

The son of Dumas, Alexandre Dumas fils (1824-1895), became the most successful playwright of the Second Empire. His 1852 drama The Lady of the Camellias ran for one hundred performances and was transformed into an opera, La Traviata by Giuseppe Verdi in 1853.

After Victor Hugo, the most prominent writer of the Second Empire was Gustave Flaubert (1821-1880). He published his first novel, Madame Bovary, in 1857, and followed it with Sentimental Education and Salammbo in 1869. He and his publisher were charged with immorality for Madame Bovary. Both were acquitted, and the publicity from the trial helped make the novel a notable artistic and commercial success.

The most important poet of the Second Empire was Charles Baudelaire (1821-1867), who published Les fleurs du mal in 1860. He also ran into trouble with the censors, and was charged with an offense to public morality. He was convicted and fined, and six poems were suppressed, but he appealed, the fine was reduced, and the suppressed poems eventually appeared. His work was attacked by the critic of Le Figaro, who complained that "everything in it which is not hideous is incomprehensible", but Baudelaire's work and innovation had an enormous influence on the poets who followed him.

The most prominent of the younger generation of writers in Paris was Émile Zola (1840-1902). His first job in Paris was as a shipping clerk for the publisher Hacehtte; later, he served as the director of publicity for the firm. He published his first stories in 1864, his first novel in 1865, and had his first literary success in 1867 with his novel Thérèse Raquin.

Another important writer of the time was Alphonse Daudet (1840-1897), who became private secretary to the half-brother and senior advisor of Napoleon III, Charles de Morny. His book Lettres de mon moulin (1866) became a French classic.

One of the most popular writers of the Second Empire was Jules Verne (1828-1905), who lived on what is now Avenue Jules-Verne. He worked at the Théâtre Lyrique and the Paris stock exchange (the Paris Bourse), while he did research for his stories at the National Library. He wrote his first stories and novels in Paris, including Journey to the Center of the Earth (1864), From the Earth to the Moon (1864), and Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (1865).

Architecture of the Second Empire

The Opera Garnier (1862-1875)

The Opera Garnier (1862-1875) The grand stairway of the Paris Opera, designed by Charles Garnier, in the style he called simply "Napoleon III"

The grand stairway of the Paris Opera, designed by Charles Garnier, in the style he called simply "Napoleon III" The interior of one of the giant glass and iron pavilions of Les Halles designed by Victor Baltard (1853-1870).

The interior of one of the giant glass and iron pavilions of Les Halles designed by Victor Baltard (1853-1870). The reading room of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Richelieu site (1854-1875), was designed by Henri Labrouste

The reading room of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Richelieu site (1854-1875), was designed by Henri Labrouste The Church of Saint Augustine (1860-1871), designed by architect Victor Baltard, had a revolutionary iron frame, but a classical Neo-Renaissance exterior.

The Church of Saint Augustine (1860-1871), designed by architect Victor Baltard, had a revolutionary iron frame, but a classical Neo-Renaissance exterior. The monumental gates of the Parc Monceau designed by the city architect Gabriel Davioud.

The monumental gates of the Parc Monceau designed by the city architect Gabriel Davioud.

The dominant architectural style of the Second Empire was eclecticism, drawing liberally from the Gothic and Renaissance styles, and the styles dominant during the reigns of Louis XV and Louis XVI. The style was described by Émile Zola, not an admirer of the Empire, as "the opulent bastard child of all the styles".[52] The best example was the Opera Garnier, begun in 1862 but not finished until 1875. The architect was Charles Garnier (1825-1898), who won the competition for the design when he was only thirty-seven. When asked by the Empress Eugénie what the style of the building was called, he replied simply, "Napoleon III". At the time, it was the largest theater in the world, but much of the interior space was devoted to purely decorative spaces: grand stairways, huge foyers for promenading, and large private boxes. Another example was the Mairie, or city hall, of the 1st arrondissement of Paris, built in 1855–1861 in a neo-Gothic style by the architect Jacques-Ignace Hittorff (1792-1867).[53]

The industrial revolution was beginning to demand a new kind of architecture: bigger, stronger, and less expensive. The new age of railways, and the enormous increase in travel that it caused, required new train stations, large hotels, exposition halls, and department stores in Paris. While the exteriors of most Second Empire monumental buildings usually remained eclectic, a revolution was taking place; based on the model of The Crystal Palace in London (1851), Parisian architects began to use cast-iron frames and walls of glass in their buildings.[54]

The most dramatic use of iron and glass was in the new central market of Paris, Les Halles (1853-1870), an ensemble of huge iron and glass pavilions designed by Victor Baltard (1805-1874) and Felix-Emmanuel Callet (1792-1854). Jacques-Ignace Hittorff also made extensive use of iron and glass in the interior of the new Gare du Nord train station (1842-1865), although the facade was perfectly neoclassical, decorated with classical statues representing the cities served by the railway. Baltard also used a steel frame in building the largest new church built in Paris during the Empire, the Church of Saint Augustine (1860-1871). While the structure was supported by cast-iron columns, the facade was eclectic. Henri Labrouste (1801-1875) also used iron and glass to create a dramatic cathedral-like reading room for the National Library, Richelieu site (1854-1875).[55]

The Second Empire also saw the completion or restoration of several architectural treasures: the wings of the Louvre Museum were finally completed; the famed stained glass windows and structure of the Sainte-Chapelle were restored by Eugène Viollet-le-Duc; and the Cathedral of Notre Dame underwent extensive restoration. In the case of the Louvre, in particular, the restorations were sometimes more imaginative than historically authentic.

Interior decoration

.jpg.webp) A salon of Napoleon III in the Louvre.

A salon of Napoleon III in the Louvre. The salon of the Empress Eugénie at the Tuileries Palace.

The salon of the Empress Eugénie at the Tuileries Palace..jpg.webp) One of the salons of Napoleon III, now in the Louvre, in the Second Empire Style. The chair in the foreground, designed for intimate conversations among three persons, was called l'indiscret, or "the indiscreet".

One of the salons of Napoleon III, now in the Louvre, in the Second Empire Style. The chair in the foreground, designed for intimate conversations among three persons, was called l'indiscret, or "the indiscreet". The chair for intimate conversations called le confident

The chair for intimate conversations called le confident

Comfort was the first priority of Second Empire furniture. Chairs were elaborately upholstered with fringes, tassels, and expensive fabrics. Tapestry work on furniture was very much in style. The structure of chairs and sofas was usually entirely hidden by the upholstery or had copper, shell, or other decorative elements as ornamentation. Novel and exotic new materials—such as bamboo, papier-mâché, and rattan—were used for the first time in European furniture, along with polychrome wood, and wood painted with black lacquer. The upholstered pouffe, or footstool, appeared, along with the angle sofa and unusual chairs for intimate conversations between two persons (Le confident) or three people (L'indiscret).

Fashion

The Empress Eugénie in 1855 (center, in white gown with lavender ribbons), surrounded by her ladies-in-waiting, painted by her favourite artist, Franz Xaver Winterhalter.

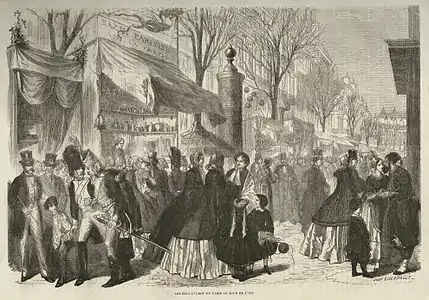

The Empress Eugénie in 1855 (center, in white gown with lavender ribbons), surrounded by her ladies-in-waiting, painted by her favourite artist, Franz Xaver Winterhalter. Paris boulevard fashion in 1853

Paris boulevard fashion in 1853 The sculptor François Jouffroy in 1865 wearing the men's fashion of the day, holding his gloves in his hand to show that he could afford them, but did not need them.

The sculptor François Jouffroy in 1865 wearing the men's fashion of the day, holding his gloves in his hand to show that he could afford them, but did not need them. By 1870, the crinoline had gone out of style, and women wore skirts that more closely fit the body.

By 1870, the crinoline had gone out of style, and women wore skirts that more closely fit the body.

Women's fashion during the Second Empire was set by the Empress Eugénie. Until the late 1860s, it was dominated by the crinoline dress, a bell-shaped dress with a very wide, full-length skirt supported on a frame of hoops of metal. The dress's waist was extremely narrow, its wear facilitated by wearing a corset with whalebone stays underneath, which also pushed up the bust. The shoulders were often bare or covered by a shawl. The Archbishop of Paris noted that women used so much material in the skirt that none seemed to be left to cover their shoulders. Paris church officials also noted with concern that the pews in a church, which normally could seat one hundred people, could seat only forty women wearing such dresses, thus the Sunday intake of donations fell. In 1867, a young woman was detained at the church of Notre-Dame-des-Victoires for stealing umbrellas and hiding them under her skirt.[56] The great expanse of the skirt was covered with elaborate lace, embroidery, fringes, and other decoration. The decoration was fantastic and eclectic, borrowing from the era of Louis XVI, the ancient Greeks, the Renaissance, or Romanticism.

In the 1860s, the crinoline dress began to lose its dominance, due to competition from the more natural "style Anglais" (English style) that followed the lines of the body. The English style was introduced by the British couturier Charles Frederick Worth and Princess Pauline von Metternich. At the end of the 1860s, the empress herself began to wear the English style.[57]

In men's fashion, the long redingote of the era of Louis-Philippe (the name came from the English term "riding-coat") was gradually replaced by the jacquette, and then the even shorter veston. The shorter jacket allowed a man to put his hands into his trouser pockets. The trousers were wide at the waist, and very narrow at the cuffs. Men wore a neutral-colored vest, usually cut low to show off highly decorated shirts with frills and buttons of paste jewellery. Men had gloves, but carried them in their hands, according to Gaston Jolivet, a prominent fashion observer of the time, in order "to prove to the population that they had the means to buy a pair of gloves without using them."[58]

Opera, Theater and Amusement

By the end of the Second Empire, Paris had 41 theaters that offered entertainment for every possible taste: from grand opera and ballet to dramas, melodramas, operettas, vaudeville, farces, parodies, and more. Their success was in part a result of the new railroads, which brought thousands of spectators from the French provinces and abroad. A popular drama that would have had a run of fifteen performances for a purely Parisian audience could now run for 150 performances with new audiences every night. Of these theaters, five had official status and received substantial subsidies from the Imperial treasury: the Opéra (800,000 francs a year); the Comédie-Francaise (240,000 francs); the Opéra-Comique (140,000 francs); the Odéon (60,000 francs), and the Théâtre Lyrique (100,000 francs).[59]

The Paris Opera

At the top of the hierarchy of Paris theaters was the Théâtre Impérial de l'Opéra (Imperial Opera Theater). The first stone of the new Paris opera house, designed by Charles Garnier, was laid in July 1862, but flooding of the basement caused the construction to proceed very slowly. Garnier himself had his office on the site to oversee every detail. As the building rose, it was covered with a large shed so that the sculptors and artists could create the elaborate exterior decoration. The shed was taken off on 15 August 1867, in time for the Paris Universal Exposition. Visitors and Parisians could see the building's glorious new exterior, but the inside was not finished until 1875, after the fall of the Empire in 1870. Opéra performances were held in the Salle Le Peletier, the theater of the Académie Royale de Musique, on the Rue Le Peletier. It was at that opera house that, on 14 January 1858, a group of Italian extreme nationalists attempted to kill Napoleon III at the entrance, by setting off several bombs that killed eight people, injured 150, and splattered the empress with blood, although the emperor was unharmed.

The opera house on the Rue Le Peletier could seat 1800 spectators. There were three performances a week, scheduled so as not to compete with the other major opera house in the city, the Théâtre-Italien. The best seats were in the forty boxes on the first balcony, which could each hold four or six persons. One of the boxes could be rented for the entire season for 7500 francs. One of the major functions of the opera house was to be a meeting place for Paris society, and for this reason the performances were generally very long, with as many as five intermissions. Ballets were generally added in the middle of operas to create additional opportunities for intermissions. Operas by the major composers of the time, notably Giacomo Meyerbeer and Richard Wagner, had their first French performances in this theater.[60]

The first French performance of Wagner's opera Tannhäuser, in March 1861, (with ballets choreographed by Marius Petipa) caused a scandal; most of the French critics and audience disliked both the music and personality of Wagner, who was present in the theater. Each performance was greeted with whistles and jeers from the first notes of overture; after three performances, the opera was pulled from the repertoire.[61] Wagner got his revenge. In February 1871, he wrote a poem, "To the German Army before Paris", celebrating the German siege of the city, which he sent to German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck. Bismarck wrote back to Wagner, "you too have overcome the resistance of the Parisians after a long struggle."[62]

The Théâtre Italien, the Théâtre-Lyrique, and the Opéra-Comique

_during_'Don_Quichotte'_1869_-_NGO_3p872.jpg.webp) The Théâtre Lyrique, on the Place du Chatelet, in 1869. It hosted the first performances of the operas Faust and Roméo et Juliette by Charles Gounod and Les pêcheurs de perles by Georges Bizet.

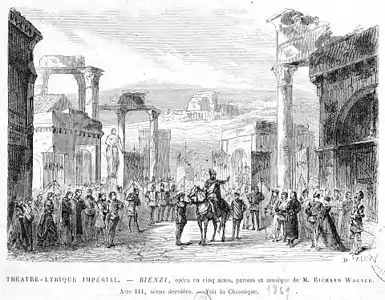

The Théâtre Lyrique, on the Place du Chatelet, in 1869. It hosted the first performances of the operas Faust and Roméo et Juliette by Charles Gounod and Les pêcheurs de perles by Georges Bizet. The Théâtre Lyrique was known for its elaborate sets and staging. This engraving depicts the last scene of a production of the opera Rienzi by Richard Wagner in 1869.

The Théâtre Lyrique was known for its elaborate sets and staging. This engraving depicts the last scene of a production of the opera Rienzi by Richard Wagner in 1869. The Salle Ventadour was the home of the Théâtre-Italien. The first French performances of the operas of Verdi were staged there, and the famed soprano Adelina Patti sang there regularly during the Second Empire.

The Salle Ventadour was the home of the Théâtre-Italien. The first French performances of the operas of Verdi were staged there, and the famed soprano Adelina Patti sang there regularly during the Second Empire.

Besides the Imperial Opera Theater, Paris had three other important opera houses: the Théâtre Italien, the Opéra-Comique, and the Théâtre-Lyrique.

The Théâtre Italien was the oldest opera company in Paris. During the Second Empire, it was based in the Salle Ventadour and hosted the French premieres of many of Verdi's operas, including Il Trovatore (1854), La Traviata (1856), Rigoletto (1857), and Un ballo in maschera (1861). Verdi conducted his Requiem there, and Richard Wagner conducted a concert of selections from his operas. The soprano Adelina Patti had an exclusive contract to sing with at the Théâtre Italien when she was in Paris.

The Théâtre-Lyrique was originally located on the Rue de Temple, the famous "Boulevard du Crime" (so-called for all of the crime melodramas that were staged there); but when that part of the street was demolished to make room for the Place de la Republique, Napoleon III built the company a new theater at the Place du Châtelet. The Lyrique was famous for putting on operas by new composers. It staged the first French performance of Rienzi by Richard Wagner; the first performance of Les pêcheurs de perles (1863), the first opera by the 24-year-old Georges Bizet; the first performances of the operas Faust (1859) and Roméo et Juliette (1867) by Charles Gounod; and the first performance of Les Troyens (1863) by Hector Berlioz.

The Opéra-Comique was located in the Salle Favart and produced both comedies and serious works. It staged the first performances of Mignon by Ambroise Thomas (1866) and of La grand'tante, the first opera of Jules Massenet (1867).

The Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens and the Théâtre des Variétés

Hortense Schneider in the title role of the operetta La Grande-Duchesse de Gérolstein by Jacques Offenbach (1867).

Hortense Schneider in the title role of the operetta La Grande-Duchesse de Gérolstein by Jacques Offenbach (1867). The interior of the Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens, where many of the operettas of Jacques Offenbach were first performed, as depicted in 1859.

The interior of the Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens, where many of the operettas of Jacques Offenbach were first performed, as depicted in 1859. A poster to advertise a production of La Grande Duchesse de Gérolstein in 1868

A poster to advertise a production of La Grande Duchesse de Gérolstein in 1868.jpg.webp) A scene from a production of La Grande Duchesse de Gérolstein in 1867.

A scene from a production of La Grande Duchesse de Gérolstein in 1867.

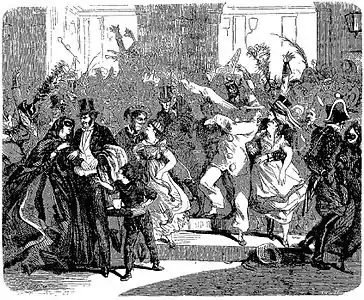

Operetta was a speciality of the Second Empire, and its master was the German-born composer and conductor Jacques Offenbach. He composed more than a hundred operettas for the Paris stage, including Orphée aux enfers (1858), La Belle Hélène (1864), La Vie parisienne (1866), and La Grande-Duchesse de Gérolstein (1867). His operettas were performed with great success at the Théâtre des Variétés and the Theatre des Bouffes-Parisiens, and he was given French citizenship and awarded the Legion of Honour by Napoleon III. The soprano Hortense Schneider was the star of his most famous operettas and was one of the most popular actresses on the stages of the Second Empire. One Paris operetta melody by Offenbach, Couplets des deux Hommes d'Armes, sung by two policemen in the operetta Geneviève de Brabant (1868), won fame in an entirely different context: it became the melody of the Marine's Hymn, the song of the United States Marine Corps, in 1918.

The Boulevard du Crime, the Cirque Napoleon and the Théâtre du Vaudeville

The Théâtre de la Gaîté, located on the Boulevard du Crime until 1862, showed popular programs of vaudeville and melodrama.

The Théâtre de la Gaîté, located on the Boulevard du Crime until 1862, showed popular programs of vaudeville and melodrama. The interior of the Théâtre des Funambules. The upper balcony, where the cheapest seats were located, was called Paradis (Paradise).

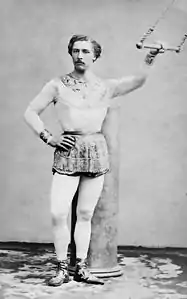

The interior of the Théâtre des Funambules. The upper balcony, where the cheapest seats were located, was called Paradis (Paradise). Jules Léotard, a gymnast and the inventor of the flying trapeze, became a Paris sensation in the 1860s. The tight-fitting gymnast's costume (a "leotard") is named for him.

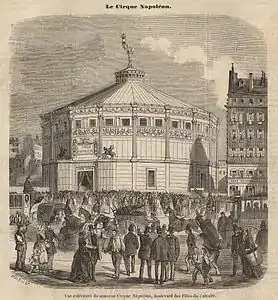

Jules Léotard, a gymnast and the inventor of the flying trapeze, became a Paris sensation in the 1860s. The tight-fitting gymnast's costume (a "leotard") is named for him. The Cirque d'Hiver, designed by the architect Jacques Ignace Hittorff, opened in 1852 as the Cirque Napoléon.

The Cirque d'Hiver, designed by the architect Jacques Ignace Hittorff, opened in 1852 as the Cirque Napoléon. The Théâtre du Vaudeville on the Place de la Bourse hosted the first performance of The Lady of the Camellias by Alexandre Dumas fils in 1852.

The Théâtre du Vaudeville on the Place de la Bourse hosted the first performance of The Lady of the Camellias by Alexandre Dumas fils in 1852.