Pact of Concord

The Pact of Concord was the provisional Constitution of Costa Rica between 1821 and 1823, officially named the Interim Fundamental Social Pact of the Province of Costa Rica.[1]

History

After the Independence of Central America the Towns' Legates Junta (Junta de Legados de los Pueblos) took over temporary control of the then Province of Costa Rica. The Junta governed Costa Rica between November 12 and December 1, 1821 and was the first autonomous government body of the newly independent Costa Rica. It had its headquarters in Cartago and was presided over by the presbyter Nicolás Carrillo y Aguirre, exercising power temporarily in Costa Rica in all branches; Executive, Legislative, Judicial, Electoral and Constituent.[2]

On October 31, 1821, the Cartago City Council, which was the de facto capital of the country, invited the different populations of the Costa Rican to send legacies to the city to decide the destiny of the young nation.[2]

The Junta decides to separate Costa Rica from the Diputación de Costa Rica y Nicaragua and draws up the Interim Fundamental Social Pact, better known as Pact of Concord, considered the country's first constitution. After this a Higher Governmental Junta is created whose president would rotate in each of the four constituent cities of Costa Rica; San José, Cartago, Heredia and Alajuela and would change president every three months.[2]

The discussion between the imperialists desiring to annex the country to the First Mexican Empire of Agustín de Iturbide and that were majority in Cartago and Heredia and the republicans that wished full independence and that predominated in San José and Alajuela, took to the end of this system of government and the outbreak of the Ochomogo War.[2]

Enactment

On October 31, 1821, the City Council of Cartago invited those of the other populations of the Partido of Costa Rica to send to that city legates with broad powers, in order to decide the way forward to the declaration of absolute independence of Spain formulated on October 11 by the Provincial Delegation of the Province of Nicaragua and Costa Rica.[1]

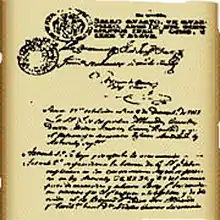

On November 12 the Junta met in Cartago, presided by the Presbyter Nicolás Carrillo y Aguirre, and as the beginning of its sessions coincided with the resignation presented by the Subaltern Political Chief Juan Manuel de Cañas-Trujillo, the Junta assumed the Government of Costa Rica in all its branches.[1] A few days later it was agreed to appoint a seven-member commission to draft a "Provisional Government Plan" that would serve as a "node of agreement" among all the represented populations. The Legates Junta assumed the character of a constituent assembly , although it did not use such a denomination. The Pact of Concord was signed in the City of Cartago.[1]

The drafting commission, in which there were representatives of different ideological tendencies, took as a basis of their work a project sent from Guatemala by the Costa Rican doctor Pablo de Alvarado y Bonilla, supporter of a liberal regime and determined adversary of the annexation to the established Mexican Empire by Don Agustín de Iturbide. On December 1, 1821, the corresponding project was submitted to the Junta of Legates, which was discussed, reformed and approved on that same date, with the name of Interim Fundamental Social Pact or Covenant of Concord.[1] The document came into force on a provisional basis, waiting to be sanctioned by a new assembly of bequests in January 1822.[1]

Content

In its original version, the constitutional text of 1821 had 58 articles, distributed in seven chapters.[1]

- Chapter I referred to the Province and expressed that Costa Rica was in absolute freedom and exclusive possession of its rights, that it would be dependent or confederate of another American State to which it agreed to adhere and that it recognized and respected civil liberty, property and other natural and legitimate rights of every person and of any people or nation.

- Chapter II was about Religion and indicated that that of the Province was and always would be Catholic, to the exclusion of any other faith, although it indicated that if a foreigner of another creed arrived in Costa Rica for reasons of commerce or transit, it would not be bothered, unless if tried to proselytize.

- Chapter III referred to citizens. In reaction to the racism of the Constitution of 1812, citizenship was attributed to all free natural men of the province or residents in it with five years of residence. The suspension or loss of citizens' rights would be governed by the provisions of the Charter of Cádiz.

- Chapter IV dealt with the Government, which was entrusted to a provisional Governing Junta, made up of seven elected members. This system would last until Costa Rica decided to which State would adhere.

- Chapter V regulated the election of the members of the government, which had to be carried out through the system of indirect universal suffrage in four grades used for the election of Deputies in the Constitution of 1812. It was also arranged that the party electors would discuss the Pact for eventual modify it and sanction it, and that its determination would be a fundamental interim law of the Province.

- Chapter VI referred to the governing body, which was called the Superior Governing Junta of Costa Rica and had to reside three months a year in each of the four major towns of the province.

- Chapter VII dealt with the restrictions of the Government, and indicated how to hold the Junta and its members accountable through a residence court.

Provisions and validity

When the Pact of Concord came into force provisionally on December 1, 1821, the sessions of the Junta were concluded and an interim Governmental Junta was inaugurated, presided over by the Presbyter Pedro José de Alvarado y Baeza.[1] This Junta remained in office until January 6, 1822, the date that the Electors Junta met in Cartago, invested with constituent power and chaired by Rafael Barroeta y Castilla. In accordance with the provisions of several transitory articles of the Pact, the Voters' Junta discussed its text and on January 10 it decided to approve it with some reforms, the most significant of which was to constitutionally consecrate the conditional annexation of Costa Rica to the First Mexican Empire, by providing that Deputies would be sent to the Constituent Congress of Mexico and the Constitution issued would be accepted. However, it was also indicated that the Pact would continue to be observed while the Constitution of the Empire was under discussion, and that Costa Rica would accept the authorities and Constitution of the Empire once settled and after the Costa Rican delegation's demands were heard.[1]

The reformed Pact was sanctioned and in full force the same January 10, 1822. However, the town of Heredia, which was in favor of the unconditional annexation to the Mexican Empire, refused to accept it. As the authorities of León, Nicaragua had agreed to the union with Mexico from October 11, 1821, Heredia decided to re-settle themselves under the jurisdiction of those and to separate from Costa Rica. As a consequence of the Heredian segregation, the three-month term established in the Pact for the Government to remain in each of the four major towns of the province was extended for one month to the benefit of Cartago, San José and Alajuela.[1]

References

- Aguilar B., Aguilar Óscar (1974). La Constitución de 1949. Antecedentes y proyecciones. San José, Costa Rica: Editorial Costa Rica.

- "Antecedentes del Estado de Costa Rica". Mensajes presidenciales.