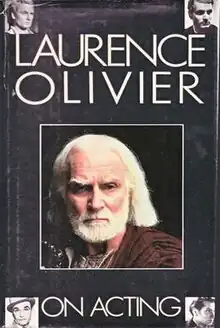

On Acting

On Acting is a book by Laurence Olivier. It was first published in 1986 when the actor was 79 years old. It consists partly of autobiographical reminiscences, partly of reflections on the actor's vocation.

First US edition | |

| Author | Laurence Olivier |

|---|---|

| Country | UK |

| Language | English |

| Publisher | Simon & Schuster (US) Weidenfeld & Nicolson (UK) |

Publication date | November 1986 |

| Media type | Print (Hardcover and Paperback) |

| Pages | 368 (hardcover edition) |

| ISBN | 0-671-63034-2 (hardcover edition) |

| OCLC | 234246359 |

Contents

Prologue

Part One: Before the Curtain

1. Beginnings

2. Lessons from the Past

Part Two: The Great Shakespearean Roles

3. Hamlet

4. Henry V

5. Macbeth

6. Richard III

7. King Lear

8. Othello

9. Antony and Cleopatra

10. The Merchant of Venice

Part Three: Contemporary Influences

11. Knights of the Theatre

12. Breakthrough

13. Colossus of the Drama

Part Four: The Silver Screen

14. Early Hollywood

15. Shakespeare on Film

16. In Front of the Camera

Part Five: Reflections

17. On Acting

Epilogue: A Letter to a Young Actress

List of Performances

Index

Quotations

From the essay 'On Acting'

I have been acting all my adult life - and before. It has stood by me and I have stood by it. It has given me much joy and some sorrow. It has taken me to places that otherwise I would not have seen. It has given me the world and great happiness. It has brought me friends and good companionship, camaraderie and brotherliness. It has taught me self-discipline and given me the retentive eye of an observer. It has enabled me love my fellow men. It has clothed me, watered me, fed me, kept me away from a bowler and a nine-till-five desk. It has given me cars, houses and holidays, bright days and cloudy ones. It has introduced me to kings and queens, presidents and princes. It has no barriers; it has no class. Whatever your background, if it decides to embrace and take you to its heart, it will hurl you up there amongst the gods. It will change your wooden clogs overnight and replace them with glass slippers.

[...]

Once you have been to the tree and tasted the fruits, some sour, some sweet, you will never be able to leave it alone again. It will get under your nails and into your pores, it will mix with your blood, and nothing will ever take it away from you. It has its ups and downs, twists and turns, great fortune and bad luck. It has its own superstitions and its own language. It has its 'in' crowds and 'out' crowds, its jealousies and its loves. It can destroy you in all sorts of canny ways with drink, drugs, success or failure. It can change charming personalities into monsters, and big egos into even bigger ones. It can make you believe your own publicity. It can make you sit on your behind and feed on past glories. It can leave you in a pile of yesterday's press cuttings and laugh at you as you wonder what happened to your real self. It is selective and very surprising. It can make you give me everything else. It will blinker you to personal relationships and destroy marriages and families. It can turn even twins against each other. It can rape you, bugger you, bless you and succour you. Its moods change with the wind. Once you have made your decision, if you believe enough, there is positively no turning back. Above all, you must remain always open and fresh and alive to any new ideas.

[...]

You must be prepared to sacrifice in order to succeed. You must set your goals high and go for them with the pugnacity of a terrier. But remember, to fall into dissipation is easy, for it is a glamorous profession, full of glorious temptations. Place a foot on the first rung and the serpents will appear beckoning with their silky tails, flattering you and begging you to bite the apple.

So many talents, good, raw and rich ones, have been battered against the walls of dissipation and left to drown. The sycophant serpents are everywhere. Because as a profession it generates glamour, the acolytes queue up to stare at, touch or, if possible entertain something that they can never be. Their admiration is genuine, but beware, actor, beware. Beware of the Greeks.

[...]

Above all, do not despair when the hand of criticism plunges into your body and claws at your soul: you must take it, accept it and smile. It is your life and your choice. And beware, look to the opposite. Do not float toward the heavens when the same patronising person places a hand on the crown of your head and breathes compliments into your vulnerable ear. Everything can change tomorrow. I suppose critics are a grim necessity. There are good ones and bad ones, and ones who simply masquerade as critics but are merely purveyors of columns of gossip, tittle-tattle signifying nothing. Poor creatures who are pushed by their pens rather than by their intellect. The good ones are essayists and of immense value to our work.

[...]

I know that, if we are foolish enough to parade ourselves between spotlight and reality, we must be prepared to receive the attention of the pen, but let me plead for thought, care and sincerity, not for mere showmanship.

[...]

I can no longer work in the theatre, but the thrill will never leave me. The lights and the combat. The intimacy between the audience and me during the soliloquies in Hamlet and Richard III - we were like lovers.

From Part Two

On Antony and Cleopatra:

It was a purely physical relationship. Two very attractive human beings determined to do wonderful things to each other. Result... suicide. There is nothing cerebral about their love: it is pure passion, lust and enjoyment. And why not? How would you feel alone in a chamber with that lady? I don't think you'd want to discuss The Times crossword.

On Antony:

It's a wonderful part. But just remember, all you future Antonys, one little word of advice: Cleopatra's got you firmly by the balls.

Why Othello is such a difficult part:

I had this fantasy, and I like to think it's probably very near the truth, that Shakespeare and Burbage went out on a binge one night, each trying to outdrink the other, the yards of ale slipping down their throats and thickening their tongues. Just before one or other slid under the alehouse table, Burbage looked at Shakespeare and said, 'I can play anything you write - anything at all'. And Shakespeare said, 'Right, I'll fix you, boy', and wrote Othello for him. I'm sure something like that must have happened.

From various other parts

When I wanted a Mississippi accent for Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, I couldn't find a single soul at the American Embassy in London who could cough me up one. The nearest was a nineteen-years-old girl from Tennessee. [...] Maureen Stapleton and the director kept saying I was fine but I wondered whether it was Mississippi enough.