Oligopeptidase

An Oligopeptidase is an enzyme that cleaves peptides but not proteins. This property is due to its structure: the active site of this enzyme is located at the end of a narrow cavity which can only be reached by peptides.

History

Background

Proteins are essential macromolecules of living organisms. They are continuously being degraded into their constituent amino acids which can be reused in the synthesis of new proteins. Every cellular protein has its own half-life time. In humans, for instance, 50% of the liver and plasma proteins are replaced in 10 days, whereas in muscles it takes 180 days. In average, every 80 days about 50% of our proteins are totally replaced.[2] Although the regulation of protein degradation is as important as their synthesis to keep each cell protein concentration at the optimum level, research in this area remained until the end of the 1970s. Up to this time, lysosomes, discovered in the 1950s by the Belgian cytologist Christian de Duve, were thought responsible for the complete digestion of intra- and extracellular proteins by the lysosomal hydrolytic enzymes.

Between the 1970s and 1980s, this view drastically changed. New experimental evidences showed that, under physiological conditions, non-lysosomal proteases were responsible for limited proteolysis of intra- and/or extracellular proteins, a concept originally conceived by Linderstᴓm-Lang in 1950.[3] Endogenous or exogenous proteins are processed by non-lysosomal proteases into intermediate-sized polypeptides, which display gene and metabolic regulation, neurologic, endocrine, and immunological roles, whose dysfunction might explain a number of pathologies. Consequently, protein degradation did not represent anymore the end of the biological function of proteins, but rather the beginning of a yet unexplored side of the biology of the cells. A number of intra- or extracellular proteases release protein fragments endowed with essential biological activities. These hydrolytic processes could be carried out by proteases such as Proteasomes, Proprotein Convertases,[4] Caspases, Rennin and Kallikreins. Among the products released by the non-lysosomal proteases are the bioactive oligopeptides such as hormones, neuropeptides and epitopes that, once released, could be modulated in their biological activities by specific peptidases, which promote the trimming, conversion and/or inactivation of the bioactive oligopeptides.

Early study

The history of oligopeptidases originates in the late 1960s, when the rabbit brain was searched for enzymes that cause inactivation of the nonapeptide bradykinin.[5] In the early and mid 1970s two thiol-activated endopeptidases, responsible for more than 90% of bradykinin inactivation, were isolated from cytosol of rabbit brain, and characterized.[6][7] They correspond to EOPA (endooligopeptidase A, EC 3.4.22.19), and Prolyl endopeptidase or Prolyl oligopeptidase (POP) (EC 3.4.21.26). Since their activities are restricted to oligopeptides (usually from 8-13 amino acid residues), and do not hydrolyze proteins or large peptides (>30 amino acid residues), they were designated oligopeptidases.[8] In the early and mid 1980s other oligopeptidases, mostly metallopeptidases, were described in the cytosol of mammalian tissues, such as the TOP (thimet oligopeptidase, EC 3.4.24.15),[9] and the neurolysin (EC 3.4.24.16).[10] Earlier on, the ACE (angiotensin-converting enzyme, EC 3.4.15.1), and the NEP (neprilysin, EC 3.4.24.11), had been described, at the end of the 1960s,[11] and in 1973,[12] respectively.

Function and clinical significance

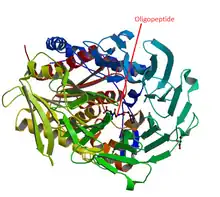

Short 'oligopeptides', predominantly smaller than 30 amino acids in length, play essential roles as hormones, in the surveillance against pathogens, and in neurological activities. Therefore, these molecules constantly need to be specifically generated and inactivated, which is the role of the oligopeptidases. Oligopeptidase is a term coined in 1979 to designate a sub-group of the endopeptidases,[8][13] which are not involved in the digestion nor in the processing of proteins like the pancreatic enzymes, proteasomes, cathepsins among many others. The prolyl-oligopeptidase or prolyl endopeptidase (POP) is a good example of how an oligopeptidase interacts with and metabolizes an oligopeptide. The peptide has first to penetrate into a 4 Å hole on the surface of the enzyme in order to reach an 8,500Å3 internal cavity, where the active site is located.[1][14] Even though the size of the peptide is crucial for its docking, the flexibility of both enzyme and ligand seems to play an essential role in determining whether a peptide bond will be hydrolyzed or not.[15][16] This contrasts with the classical specificity of proteolytic enzymes, which derives from the chemical features of the amino acid side chains around the scissile bond.[17] A number of enzymatic studies supports this conclusion.[15][18] This peculiar specificity suggests that the concept of conformational melding of the peptides used to explain the interaction between T-cell receptor and its epitopes,[19] seems more likely to describe the enzymatic specificity of the oligopeptidases. Another important feature of the oligopeptidases is their sensitivity to the oxidation-reduction (redox) state of the environment.[6][7] An "on-off" switch provides a qualitative change in peptide binding and/or degradation activity. However, the redox state only exerts strong influence on cytosolic enzymes (TOP[20][21] neurolysin[22][23] POP[24] and Ndl-1 oligopeptidase,[25][26] not on cytoplasmic membrane oligopeptidases (angiotensin-converting enzyme and neprilysin). Thus, the redox state of the intracellular environment very likely modulates the activity of the thiol-sensitive oligopeptidases, thereby contributing to define the fate of proteasome products, driving them to complete hydrolysis, or, alternatively, converting them into bioactive peptides, such as the MHC-Class I peptides.[16][27][28]

Since the discovery of the neuropeptides and peptide hormones from the central nervous system (ACTH, β-MSH, endorphin, oxytocin, vasopressin, LHRH, enkephalins, substance P), and of peripheral vasoactive peptides (angiotensin, bradykinin) around the middle of last century, the number of known biologically active peptides has exponentially increased. They are signaling molecules, participating in all essential aspects of life, from physiological homeostasis (as neuropeptides, peptide hormones, vasoactive peptides), to immunological defense (as MHC class I and II, cytokinins), and as regulatory peptides displaying more than a single action. These peptides result from partial proteolysis of intracellular or extracellular protein precursors performed by several processing enzymes or protease complexes (rennin, kallikreins, calpains, prohormone convertases, proteasomes, endosomes, lysosomes), which convert proteins into peptides, including those with biological activities. The resulting protein fragments of various sizes are either readily degraded into free amino acids,[29] or captured by oligopeptidases, whose peculiar binding and/or catalytic properties allow them to fulfill their physiological roles by trimming inactive peptide precursors leading to their active form,[27][11] converting bioactive peptides into novel ones.,[30] inactivating them, thus restraining the continuous activation of specific receptors,[6][7] or protecting the newly generated bioactive peptide from further degradation, suggesting a peptide chaperon-like activity.[16][28] TOP, a ubiquitous cytosolic oligopeptidase, is a remarkable example of how this enzyme could play an essential role in immune defense against cancer cells.[27] It has also been successfully used as a hook to fish novel bioactive peptides from cytosol of cells.[31]

The involvement of peptides in cell-cell interactions and in neuropsychiatric, autoimmune, and neurovegetative diseases are waiting for peptidomics[32] and gene silencing approaches, which will expedite the formation of new concepts in an emerging era for oligopeptidases.

The participation of oligopeptidases in a number of pathologies has long been reported. The ACE has benefited the most from a thorough knowledge on the enzyme structure and its mechanism of catalysis leading to the better understanding of its role in cardiovascular pathologies and therapeutics. Accordingly, for over 30 years, the treatment of human arterial hypertension has taken advantage of ACE inhibition by active site-directed inhibitors like captopril, enalapril, lisinopril, and others.[33] For the other oligopeptidases, especially those involved in human diseases, the existing studies are promising but not yet as developed as for the ACE. Some examples are: a) the POP of nervous tissues has been suggested to be involved in neuropsychiatric disorders, like in post-traumatic stress, depression, mania, nervous bulimia, anorexia, and schizophrenia, as reviewed in.[14] b) NEP has been involved in cancer;[34] c) the TOP has been involved in tuberculosis[28] and in cancer;[27] d) the EOPA or NUDEL/EOPA (NDEL1/EOPA gene product) has been involved in neuronal migration during the cortex formation in human embryo (lissencephaly) and neurite outgrowth in adults, as in schizophrenia.[26][35] Coincidentally, an activity related to the development of nervous tissue has been suggested for POP, nevertheless not involving its proteolytic activity.[36] The absence of an oligopeptidase in the intestine was also responsible for the decreased serum zinc levels observed in patients who have the disease Acrodermatitis Enteropathica.[37]

References

- Fülöp V, Böcskei Z, Polgár L (1998). "Prolyl oligopeptidase: an unusual beta propeller domain regulates proteolysis". Cell. 94 (2): 161–170. doi:10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81416-6. PMID 9695945. S2CID 17074611.

- Bachmair A, Finley D, Varshavsky A (Oct 1986), "In vivo half-life of a protein is a function of its amino-terminal residue", Science, 234 (4773): 179–86, Bibcode:1986Sci...234..179B, doi:10.1126/science.3018930, PMID 3018930

- Linderstrøm-Lang K (1950), "In vivo half-life of a protein is a function of its amino-terminal residue", Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol, 14: 117–26, doi:10.1101/sqb.1950.014.01.016, PMID 15442905

- Seidah NG (Mar 2011), "What lies ahead for the proprotein convertases?", Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1220 (1): 149–61, Bibcode:2011NYASA1220..149S, doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05883.x, PMID 21388412, S2CID 22864082

- Camargo AC, Graeff F (1969). "Subcellular distribution and properties of the bradykinin inactivation system in rabbit brain homogenates". Biochem Pharmacol. 18 (2): 548–549. doi:10.1016/0006-2952(69)90235-4. PMID 5778163.

- Camargo AC, Shapanka R, Greene LJ (April 1973). "Preparation, assay, and partial characterization of a neutral endopeptidase from rabbit brain". Biochemistry. 12 (9): 1838–44. doi:10.1021/bi00733a028. PMID 4699240.

- Oliveira EB, Martins AR, Camargo AC (1976). "Isolation of brain endopeptidases: Influence of size and sequence of substrates structurally related to bradykinin". Biochemistry. 15 (9): 1967–1974. doi:10.1021/bi00654a026. PMID 5120.

- Camargo AC, Caldo H, Reis ML (1979). "Susceptibility of a peptide derived from bradykinin to hydrolysis by brain endo-oligopeptidases and pancreatic proteinases". J Biol Chem. 254 (12): 5304–5307. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)50595-0. PMID 447650.

- Orlowski M, Michaud C, Chu TG (1983). "A soluble metalloendopeptidase from rat brain. Purification of the enzyme and determination of specificity with synthetic and natural peptides". Eur J Biochem. 135 (1): 81–88. doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1983.tb07620.x. PMID 6349998.

- Checler F, Vincent JP, Kitabgi P (August 1983). "Degradation of neurotensin by rat brain synaptic membranes: involvement of a thermolysin-like metalloendopeptidase (enkephalinase), angiotensin-converting enzyme, and other unidentified peptidases". J. Neurochem. 41 (2): 375–84. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.1983.tb04753.x. PMID 6308159. S2CID 21440301.

- Erdös, Ervin G.; Tan, Fulong; Skidgel, Randal A. (2010). "Angiotensin I–Converting Enzyme Inhibitors Are Allosteric Enhancers of Kinin B1 and B2 Receptor Function". Hypertension. 55 (2): 214–220. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.144600. PMC 2814794. PMID 20065150.

- Kerr MA, Kenny AJ (1974). "The purification and specificity of a neutral endopeptidase from rabbit kidney brush border". Biochem J. 137 (3): 477–488. doi:10.1042/bj1370477. PMC 1166147. PMID 4423492.

- Barrett AJ, Rawlings ND (July 1992). "Oligopeptidases, and the emergence of the prolyl oligopeptidase family". Biol. Chem. Hoppe-Seyler. 373 (2): 353–60. doi:10.1515/bchm3.1992.373.2.353. PMID 1515061.

- Li M, Chen C, Davies DR, Chiu TK (2010). "Induced-fit mechanism for prolyl endopeptidase". J Biol Chem. 285 (28): 21487–21495. doi:10.1074/jbc.M109.092692. PMC 2898448. PMID 20444688.

- Jacchieri SG, Gomes MD, Juliano L, Camargo AC (June 1998). "A comparative conformational analysis of thimet oligopeptidase (EC 3.4.24.15) substrates". The Journal of Peptide Research. 51 (6): 452–9. doi:10.1111/j.1399-3011.1998.tb00644.x. PMID 9650720.

- Portaro F, Gomes MD, Cabrera A, et al. (1999). "Thimet oligopeptidase and the stability of MHC class I epitopes in macrophage cytosol". Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 255 (3): 596–601. doi:10.1006/bbrc.1999.0251. PMID 10049756.

- Schechter I, Berger A (1967). "On the size of the active site in proteases I. Papain". Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 27 (2): 157–162. doi:10.1016/s0006-291x(67)80055-x. PMID 6035483.

- Camargo AC, Gomes MD, Reichl AP, Jacchieri SG, Juliano L (1997). "Structural features which make oligopeptides susceptible to hydrolysis by recombinant endooligopeptidase 24.15 (EC 3.4.24.15)". Biochem J. 324 (Pt 2): 517–522. doi:10.1042/bj3240517. PMC 1218460. PMID 9182712.

- Backer BM, Scott DR, Blevins SJ, Hawse WF (2012). "Structural and dynamic control of T-cell receptor specificity, cross-reactivity, and binding mechanism". Immunological Reviews. 250 (1): 10–31. doi:10.1111/j.1600-065X.2012.01165.x. PMID 23046120. S2CID 9837194.

- Shrimpton CN, Glucksman MJ, Lew RA, et al. (1997). "Thiol activation of endopeptidase (EC 3.4.24.15). A novel mechanism for the regulation of the catalytic activity". J Biol Chem. 272 (28): 17395–17399. doi:10.1074/jbc.272.28.17395. PMID 9211880.

- Ray K, Hines CS, Coll-Rodriguez J, Rodgers DW (2004). "Crystal structure of human thimet oligopeptidase provides insight into substrate recognition, regulation, and localization". J Biol Chem. 279 (19): 20480–20489. doi:10.1074/jbc.M400795200. PMID 14998993.

- Kato A, Sugiura N, et al. (1997). "Targeting of endopeptidase 24.16 to different subcellular compartments by alternative promoter usage". J Biol Chem. 272 (24): 15313–15322. doi:10.1074/jbc.272.24.15313. PMID 9182559.

- Santos KL, Vento MA, et al. (2013). "The effects of para-chloromercuribenzoic acid and different oxidative and sulfhydryl agents on a novel, non-AT1, non-AT2 angiotensin binding site identified as neurolysin". Regul Pept. 184: 104–114. doi:10.1016/j.regpep.2013.03.021. PMC 4152863. PMID 23511333.

- Fulöp V, Szeltner Z, Polgár L (2000). "Catalysis of serine oligopeptidases is controlled by a gating filter mechanism". EMBO Rep. 1 (3): 277–281. doi:10.1093/embo-reports/kvd048. PMC 1083722. PMID 11256612.

- Gomes MD, Juliano L, et al. (1993). "Dynorphin-derived peptides reveal the presence of a critical cysteine for the activity of brain endo-oligopeptidase A". Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 197 (2): 501–507. doi:10.1006/bbrc.1993.2507. PMID 7903528.

- Hayashi MA, Portaro FC, Bastos MF, et al. (2005). "Inhibition of NUDEL (nuclear distribution element-like)-oligopeptidase activity by disrupted-in-schizophrenia 1". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 102 (10): 3828–3833. Bibcode:2005PNAS..102.3828H. doi:10.1073/pnas.0500330102. PMC 553309. PMID 15728732.

- Kessier JH, Khan S, Seifert U et al. (2011) Antigen processing by nardilysin and thimet oligopeptidase generates cytotoxic T cell epitopes. Nature Immunology- http://www.nature.com/ni/journal/v12/n1/full/ni.1974.html

- Silva CL, Portaro FC, Bonato VL, et al. (1999). "Thimet Oligopeptidase (EC.3.4.24.15) is a novel protein on the route of MHC class I antigen presentation". Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 255 (3): 591–595. doi:10.1006/bbrc.1999.0250. PMID 10049755.

- Goldberg AL (2003). "Protein degradation and protection against misfolded or damaged proteins". Nature. 426 (6968): 895–899. Bibcode:2003Natur.426..895G. doi:10.1038/nature02263. PMID 14685250. S2CID 395463.

- Camargo AC, Oliveira EB, Toffoletto O, et al. (1997). "Brain endo-oligopeptidase A, a putative enkephalin converting enzyme". J Neurochem. 48 (4): 1258–1263. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.1987.tb05655.x. PMID 2880931. S2CID 27763093.

- Gelman JS, Sironi J, Castro LM, et al. (2010). "Hemopressins and other hemoglobin-derived peptides in mouse brain: comparison between brain, blood, and heart peptidome and regulation in Cpefat/fat mice". J. Neurochem. 113 (4): 871–880. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06653.x. PMC 2867603. PMID 20202081.

- Gelman JS, Sironi J, Castro LM, et al. (2011). "Peptidomic analysis of human cell lines". J Proteome Res. 10 (4): 1583–1592. doi:10.1021/pr100952f. PMC 3070057. PMID 21204522.

- Norris, S.; Weinstein, J.; Peterson, K.; Thakurta, S. (2010). "Drug Class Review: Direct Renin Inhibitors, Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitors, and Angiotensin II Receptor Blockers: Final Report". Drug Class Reviews. Oregon Health & Science University. PMID 21089241.

- [Maguer-Satta V, Besançon R, Bachelard-Cascale E (2011). Concise Review: Neutral Endopeptidase (NEP/CD10): a Multifaceted Environment Actor in Stem Cells, Physiological Mechanisms and Cancer. Stem Cells Jan 7; see www.StemCells.com for supporting information available online]

- Hayashi MA, Guerreiro JR, Charych E, et al. (2010). "Assessing the role of endooligopeptidase activity of Ndel1 (nuclear-distribution gene E homolog like-1)in neurite outgrowth". Mol Cell Neurosci. 44 (4): 353–361. doi:10.1016/j.mcn.2010.04.006. PMID 20462516. S2CID 28105773.

- Hannula MJ, Männistö PT, Myöhänen TT (2010). "Sequential Expression, Activity and Nuclear Localization of Prolyl Oligopeptidase Protein in the Developing Rat Brain". Dev Neurosci. 33 (1): 38–47. doi:10.1159/000322082. PMID 21160163. S2CID 39094074.

- Beigi, Pooya Khan Mohammd; Maverakis, Emanual (2015). "Acrodermatitis Enteropathica: A Clinician's Guide".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)