New Labour

New Labour was a period in the history of the British Labour Party from the mid to late 1990s until 2010 under the leadership of Tony Blair and Gordon Brown. The name dates from a conference slogan first used by the party in 1994, later seen in a draft manifesto which was published in 1996 and titled New Labour, New Life for Britain. It was presented as the brand of a newly reformed party that had altered Clause IV and endorsed market economics. The branding was extensively used while the party was in government between 1997 and 2010. New Labour was influenced by the political thinking of Anthony Crosland and the leadership of Blair and Brown as well as Peter Mandelson and Alastair Campbell's media campaigning. The political philosophy of New Labour was influenced by the party's development of Anthony Giddens' Third Way which attempted to provide a synthesis between capitalism and socialism. The party emphasised the importance of social justice, rather than equality, emphasising the need for equality of opportunity and believed in the use of markets to deliver economic efficiency and social justice.

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Leader of the Opposition

Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

Policies

Appointments

First ministry and term

Second ministry and term

Third ministry and term

Post–Prime Minister

|

||

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Shadow Chancellor

Chancellor of the Exchequer

Policies

Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

Post–Prime Minister

|

||

The New Labour brand was developed to regain trust from the electorate and to portray a departure from their traditional socialist policies which was criticised for its breaking of election promises and its links between trade unions and the state, and to communicate the party's modernisation to the public. Calls for modernisation became prominent following Labour's heavy defeat in the 1983 general election, with the new Labour leader, Neil Kinnock, who came from the party's soft left Tribune Group of Labour MPs, calling for a review of policies that led to the party's defeat, and for improvements to the party's public image to be made by Peter Mandelson, a former television producer. Following the leadership of Neil Kinnock and John Smith, the party under Tony Blair attempted to widen its electoral appeal under the New Labour tagline and by the 1997 general election it had made significant gains in the middle class; resulting in a landslide victory. Labour maintained this wider support at the 2001 general election and won a third consecutive victory in the 2005 general election for the first time ever in the history of the Labour Party. However, their majority was significantly reduced from four years previously.

In 2007, Blair resigned from the party leadership after thirteen years and was succeeded as Prime Minister by his Chancellor of the Exchequer, Gordon Brown. Labour lost the 2010 general election which resulted in the first hung parliament in thirty-six years and led to the creation of a Conservative–Liberal Democrat coalition government. Brown resigned as Prime Minister and as Labour Party leader shortly thereafter. He was succeeded as party leader by Ed Miliband, who abandoned the New Labour branding and moved the Labour Party's political stance further to the left under the branding One Nation Labour.

History

First elected to parliament as the Member of Parliament (MP) for Sedgefield, County Durham at the 1983 general election, Tony Blair became the leader of the Labour Party in 1994[1] after winning 57% of the vote in that year's leadership election, defeating John Prescott and Margaret Beckett.[2] His first shadow cabinet role came in November 1988, when Neil Kinnock appointed him as Shadow Secretary of State for Energy and in July 1992 was promoted to the role of Shadow Home Secretary on the election of John Smith as Leader of the Labour Party.

Gordon Brown, who went on to hold senior positions in Blair's Labour government before succeeding him as Prime Minister in June 2007, was not a candidate in the 1994 leadership election because of an agreement between the two made in 1994 in which Brown promised not to run for election. The media has since speculated that Blair agreed to stand down and allow Brown the premiership in the future, although Blair's supporters have contended that such a deal never took place.[3] The term New Labour was coined by Blair in his October 1994 Labour Party Conference speech[4] as part of the slogan "new Labour, new Britain".[5] During this speech, Blair announced the modification of Clause IV of the party's constitution which abandoned Labour's attachment to nationalisation and embraced market economics. The new version of the clause committed Labour to a balance of market and public ownership and to balance creation of wealth with social justice.[6] Blair argued for increased modernisation at the conference, asserting that "parties that do not change die, and [Labour] is a living movement not a historical monument".[7] During the period from 1994 to 1997, after Blair's election as party leader, Labour managed to reverse decades of decline in party membership by increasing the number by around 40%,[8] increasing its capacity to compete for office whilst also legitimising the leadership of Blair.

In 1997, New Labour won a landslide victory at the general election after eighteen years of Conservative government, winning a total of 418 seats in the House of Commons—the largest victory in the party's history.[9] The party was also victorious in 2001 and 2005, making Blair Labour's longest-serving Prime Minister and the first to win three consecutive general elections. He was also the first Labour leader to win a general election since Harold Wilson in 1974.[10]

In the months following Labour's 1997 election victory, referendums were held in Scotland and Wales regarding devolution. There was a clear majority supporting devolution in Scotland and a narrower majority in Wales—Scotland received a stronger degree of devolution than Wales. The Labour government passed laws in 1998 to establish a Scottish Parliament and Welsh Assembly and the first elections for these were held in 1999.[11] Blair attempted to continue peace negotiations in Northern Ireland by offering the creation of a regional parliament and government. In 1998, the Good Friday Agreement was made, allowing for a 108-member elected assembly and a power-sharing arrangement between nationalists and unionists. Blair was personally involved in these negotiations.[12] The Fabian Society was a forum for New Labour ideas and for critical approaches from across the party.[13] The most significant Fabian contribution to Labour's policy agenda in government was Ed Balls's 1992 pamphlet advocating Bank of England independence. In 1998, Blair and his New Labour government introduced the Human Rights Act. This was made to give UK law what the European convention of human rights had established. It was given the royal assent on the 9 November 1998, but it was not truly put in place until early October 2000.

After the United States strikes on Afghanistan and Sudan in 1998, Blair released a statement supporting the actions.[14] He lent military support to the United States' 2001 invasion of Afghanistan.[15] In March 2003, the Labour government, fearing Saddam Hussein's alleged access to weapons of mass destruction, participated in the American-led invasion of Iraq.[16] British intervention in Iraq promoted public protest. Crowds numbering 400,000 and more demonstrated in October 2002 and again the following spring. On 15 February 2003, over 1,000,000 people demonstrated against the war in Iraq and 60,000 marched in Manchester before the Labour Party conference, with the demonstrators' issues including British occupation of Afghanistan and the forthcoming invasion of Iraq.[17]

In June 2007, Blair resigned as the leader of the Labour Party and Gordon Brown, previously the Chancellor of the Exchequer, succeeded him following the 2007 Labour Party conference. Three years earlier, Blair had announced that he would not be contesting a fourth successive general election as Labour Party leader if he won the 2005 general election.[18] Brown initially had strong public support and plans for a quick general election were widely publicised, although they never were officially announced.[19] On 18 February 2008, Chancellor of the Exchequer Alistair Darling announced that the failing bank Northern Rock would be nationalised, supporting it with loans and guarantees of £50,000,000,000. The bank had been destabilised by the subprime mortgage crisis the previous year in the United States and a private buyer of the bank could not be found.[20]

The 2010 general election ended in a hung parliament[21] in which Labour won 258 seats, 91 fewer than in 2005.[22] Following failure to achieve a coalition agreement with the Liberal Democrats, Brown announced his intention to resign as leader of the party on 10 May[23] and resigned as the Prime Minister the following day.[24] Shortly thereafter, David Cameron and Nick Clegg announced the formation of a coalition between the Conservatives and Liberal Democrats.[25] Cameron became the Prime Minister and Clegg the Deputy Prime Minister of a cabinet that contained eighteen Conservative ministers and five Liberal Democrat ministers.[26] In announcing his intention to run for the leadership, David Miliband declared that the New Labour era was over.[27] Following the publication of Blair's memoirs on 1 September 2010, Ed Miliband said: "I think it is time to move on from Tony Blair and Gordon Brown and Peter Mandelson and to move on from the New Labour establishment and that is the candidate that I am at this election who can best turn the page. I think frankly most members of the public will want us to turn the page".[28] Miliband won the leadership election and was able to mobilise support from the trade union electorate.[29] In a July 2011 speech, Blair stated that New Labour died when he left office and Brown assumed the party leadership, claiming that from 2007 the party "lost the driving rhythm".[30] Nonetheless, New Labour's Third Way influenced a range of centre-left political parties across the world.[31]

Political branding

.jpg.webp)

Once New Labour was established, it was developed as a brand, portrayed as a departure from Old Labour, the party of pre-1994[32] which had been criticised for regularly betraying its election promises and was linked with trade unionism, the state and benefit claimants.[33][34] Mark Bevir argues that another motivation for the creation of New Labour was as a response to the emergence of the New Right in the preceding decades.[35] The previous two party leaders Neil Kinnock and John Smith had begun efforts to modernise the party as a strategy for electoral success before Smith died in 1994.[36] Kinnock undertook the first wave of modernisation between the 1987 and 1992 general elections, with quantitative research conducted by Anthony Heath and Roger Jowell indicating that the electorate viewed Labour as more moderate and electable in 1992 than in 1987,[37] arguably legitimising the arguments for increased modernisation. However, Smith's approach which was dubbed (sometimes pejoratively) "one more heave" was perceived as too timid by modernisers like Blair, Brown and Mandelson. They felt that his cautious approach which sought to avoid controversy and win the next election by capitalising on the unpopularity of the Conservative government was not sufficient.[38][39][40][41][42] New Labour also used the party's brand to continue this modernisation and it was used to communicate the modernisation of the party to the public.[43] The party also began to use focus groups to test whether their policy ideas were attractive to swing voters.[44] Its purpose was to reassure the public that the party would provide a new kind of governance and mitigate fears that a Labour government would return to the labour unrest that had characterised its past.[45] Blair explained that modernisation was "about returning Labour to its traditional role as a majority mainstream party advancing the interests of the broad majority of people".[46]

While the party was in power, press secretary Alastair Campbell installed a centralised organisation to co-ordinate government communication and impose a united message to be delivered by ministers. This process, known as "Millbankization"[47] in reference to the campaign headquarters of Labour at the Millbank, was strict but very effective.[48] Charlie Whelan, Brown's press officer, was often in conflict with Campbell because of the former's attempts to brief the press by his own initiatives—this continued until his resignation in 1999. Campbell followed a professional approach to media relations to ensure that a clear message was presented and the party planned stories in advance to ensure a positive media reaction.[49] Campbell used his own experience in journalism as he was known for his attention to detail and effective use of sound bites. Campbell developed a relationship with News International, providing their newspapers with early information in return for positive media coverage.[50]

In 2002, Philip Gould, a policy advisor to the Labour Party, wrote to the party's leadership that the brand had become contaminated and an object of criticism and ridicule, undermined by an apparent lack of conviction and integrity. The brand was weakened by internal disputes and the apparent failure to deal with issues.[51] This assessment was supported by Blair, who argued that the government needed to spend more time working on domestic affairs, develop a unifying strategy and create "eye-catching initiatives". Blair also announced the need to be more assertive in foreign affairs.[52]

The leaders of New Labour therefore created and ran an efficient and calculated media-handling strategy in an effort to increase electoral success. Florence Faucher-King and Patrick Le Galés note that "by 2007 the party had been emptied of its capacities for intermediation with society and, in the space of 10 years, lost half of its membership. But it had become a formidable machine for winning elections".[53]

Electoral support

Under Neil Kinnock, Labour attempted to widen its electoral support from narrow class divisions. After Blair took the leadership, the party made significant gains in higher social classes and won 39% support from managers and administrators in the 1997 election, more than in previous elections that the party had lost.[54] This was due to the calculated targeting of C1 and C2 voters by the Labour campaign and an anti-Conservative vote as opposed to an endorsement of Labour.[55] Labour won greater support among younger voters than older, but there was no significant gender difference.[56] During the 1980s, much of Labour's support had retreated into industrial areas of the north and in 1997 Labour performed much better in the south of England.[57][58] In the elections of 2001 and 2005, Labour maintained much of the middle-class support that it had won in 1997.[59] According to academics Charles Pattie and Ron Johnston, Labour's landslide in 1997 was achieved through Labour's strong performance in opposition, their modernisation efforts and moderate policies. These all encouraged many Conservative voters to abstain as the landslide was seen by many as a foregone conclusion.[60] The 2001 election resulted in significant drops in turnout in Labour heartland seats which has been attributed to voters regarding the re-election of Labour incumbents as a foregone conclusion, coupled with discontent surrounding Labour's perceived inability to deliver significant improvements in public services during their first term.[61] In 2005, Labour's support was much lower than in the previous two elections which David Rubinstein has attributed to anger at the war in Iraq and towards Blair himself.[62]

Professors Geoffrey Evans, John Curtice and Pippa Norris of Strathclyde University published a paper considering the incidence of tactical voting in the 1997 general election. Their studies showed that tactical voting increased in 1997—there was a strong increase in anti-Conservative voting and a decrease in anti-Labour tactical voting.[63] Political commentators Neal Lawson and Joe Cox wrote that tactical voting helped to provide New Labour with its majorities in 1997, 2001 and 2005, arguing that the party won because of public opposition to the Conservative Party. The party declared after its victory that it "won as New Labour and would govern as New Labour", but Cox and Lawson challenged this view, suggesting that the party won on account of public opposition to the Conservative Party.[64]

Key figures

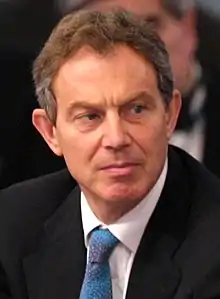

Tony Blair

Tony Blair became the leader of the Labour Party after 1994's leadership election[1] and coined the term New Labour in that October's party conference.[4] Blair pursued a Third Way philosophy that sought to use the public and private sectors to stimulate economic growth and abandon Labour's commitment to nationalisation.[65] Blair's approach to government included a greater reliance on the media, using that to set the national policy agenda, rather than Westminster. He spent considerable resources maintaining a good public image which sometimes took priority over the cabinet. Blair adopted a centralised political agenda in which cabinet ministers took managerial roles in their departments and strategic vision was to be addressed by the Prime Minister.[66] Ideologically, Blair believed that individuals could only flourish in a strong society and this was not possible in the midst of unemployment.[67]

Tony Blair served as Prime Minister, from 1997 to 2007.

Gordon Brown

Gordon Brown was an important figure in Blair's Labour government and played a key role in developing the party's philosophy. Brown served as Shadow Chancellor of the Exchequer from 1992 to 1997 and was appointed Chancellor of the Exchequer following Labour's election victory in 1997.[68] He attempted to control public spending and sought to increase the funding for education and healthcare. His economic strategy was market-based, attempting to reform the welfare state through a tax credit scheme for poorer working families and assigned the Bank of England to set interest rates.[69]

Peter Mandelson

In 1985, Peter Mandelson was appointed as the Labour Party's director of communications. Previously, he had worked in television broadcasting and helped the party become increasingly effective at communication and more concerned with its media image, especially with non-partisans.[70] Mandelson headed the Campaigns and Communications Directorate (established in 1985) and initiated the Shadow Communications Agency. He oversaw Labour's relationship with the media and believed in the importance of the agenda-setting role of the press. He felt that the agenda of the press (broadsheets in particular) would influence important political broadcasters.[71] In government, Mandelson was appointed minister without portfolio to co-ordinate the various government departments.[72] In 1998, he resigned as a cabinet minister after being accused of financial impropriety.[73]

In 2021, it was reported by The Times that Mandelson had been advising Labour leader Keir Starmer on moving the party beyond Corbyn's leadership and broadening its electoral appeal.[74]

Alastair Campbell

Alastair Campbell was the Labour Party's Press Secretary and led a strategy to neutralise the influence of the press which had weakened former Labour leader Neil Kinnock and create allies for the party.[75] While in government, Campbell established a Strategic Communications Unit, a central body whose role was to co-ordinate the party's media relations and ensure that a unified image was presented to the press.[49] Because of his background in tabloid journalism, Campbell understood how different parts of the media would cover stories. He was a valued news source for journalists because he was close to Blair—Campbell was the first press secretary to regularly attend cabinet meetings.[50]

Political philosophy

New Labour developed and subscribed to the Third Way, a platform designed to offer an alternative "beyond capitalism and socialism".[76] The ideology was developed to make the party progressive and attract voters from across the political spectrum.[77] According to Florence Faucher-King and Patrick Le Galés, "New Labour's leadership was convinced of the need to accept a globalized capitalism and join forces with the middle classes, who were often hostile to the Unions",[53] therefore shaping policy direction. New Labour offered a middle way between the neoliberal market economics of the New Right which it saw as economically efficient; and the ethical reformism of post-1945 Labour which shared New Labour's concern for social justice.[78] New Labour's ideology departed with its traditional beliefs in achieving social justice on behalf of the working class through mass collectivism. Blair was influenced by ethical and Christian socialist views and used these to cast what some consider a modern form of socialism or liberal socialism.[79]

Social justice

New Labour tended to emphasise social justice rather than the equality which was the focus of previous Labour governments and challenged the view that social justice and economic efficiency are mutually exclusive. The party's traditional attachment to equality was reduced as minimum standards and equality of opportunity were promoted over the equality of outcome. The Commission on Social Justice set up by John Smith reported in 1994 that the values of social justice were equal worth of citizens, equal rights to be able to meet their basic needs, the requirement to spread opportunities as much as possible and the need to remove unjustified inequalities. The party viewed social justice primarily as the requirement to give citizens equal political and economic liberty and also as the need for social citizenship. It encompasses the need for equal distribution of opportunity, with the caveat that things should not be taken from successful people to give to the unsuccessful.[80]

Economics

New Labour accepted the economic efficiency of markets and believed that they could be detached from capitalism to achieve the aims of socialism while maintaining the efficiency of capitalism. Markets were also useful for giving power to consumers and allowing citizens to make their own decisions and act responsibly. New Labour embraced market economics because they believed they could be used for their social aims as well as economic efficiency.[78] The party did not believe that public ownership was efficient or desirable, ensuring that they were not seen to be ideologically pursuing centralised public ownership was important to the party. In government, the party relied on public-private partnerships and private finance initiatives to raise funds and mitigate fears of a tax and spend policy or excessive borrowing.[81] New Labour maintained Conservative spending plans in their first two years in office and, during this time, Gordon Brown earned the reputation as an "Iron Chancellor" with his "Golden Rule" and conservative handling of the budget.[82][83]

Welfare

Welfare reforms proposed by New Labour in their 2001 manifesto included Working Families Tax Credit, the National Childcare Strategy and the National Minimum Wage. Writing in Capital & Class, Chris Grover argued that these policies were aimed at promoting work and that this position dominated New Labour's position on welfare. He considered the view that New Labour's welfare reforms were workfarist and argued that in this context it must refer to social policy being put in line with market economic growth. Gower proposed that under New Labour this position was consolidated through schemes to encourage work.[84]

Crime

Parts of New Labour's political philosophy linked crime with social exclusion and pursued policies to encourage partnerships between social and police authorities to lower crime rates whereas other areas of New Labour's policy maintained a traditional approach to crime, Tony Blair's approach to crime is quoted as being 'Tough on crime, Tough on the causes of crime'.[85] The first government under New Labour spent a smaller percentage of the budget on crime than the previous Tory government, however the second Labour government spent practically double (roughly 6.5% of the budget), Finally the third Labour government spent roughly the same percentage of the budget on crime as the first. Incidents of crime did drastically decrease under New Labour, from around 18,000 in 1995 to 11,000 in 2005–6, yet this doesn't account for the decrease in police reports that occurred as well during this time.

The prison population in 2005 rose to over 76,000, mostly owing to the increasing length of sentences. Following the September 11 attacks, the Labour government attempted to emphasise counter-terrorism measures. From 2002, the government followed policies aimed at reducing anti-social behaviour;[86] in the 1998 Crime and Disorder Act, New Labour introduced Anti-social behaviour orders.[87] Under this Labour Government, the '7/7' bombings took place, the first Islamic suicide attack and most deadly since the bombing of Pan Am Flight 103.

Multiculturalism

Controversy on the subject came to the fore when Andrew Neather—a former adviser to Jack Straw, Tony Blair and David Blunkett—said that Labour ministers had a hidden agenda in allowing mass immigration into Britain. This alleged conspiracy has become known by the sobriquet Neathergate.[88]

According to Neather, who was present at closed meetings in 2000, a secret government report called for mass immigration to change Britain's cultural make-up and that "mass immigration was the way that the government was going to make the UK truly multicultural". Neather went on to say that "the policy was intended—even if this wasn't its main purpose—to rub the right's nose in diversity and render their arguments out of date".[89][90] Neather later stated that his words had been twisted, saying: "The main goal was to allow in more migrant workers at a point when—hard as it is to imagine now—the booming economy was running up against skills shortages. [...] Somehow this has become distorted by excitable Right-wing newspaper columnists into being a "plot" to make Britain multicultural. There was no plot".[91]

In February 2011, the then Prime Minister David Cameron stated that the "doctrine of state multiculturalism" (promoted by the previous Labour government) had failed and will no longer be state policy.[92] He stated that the United Kingdom needed a stronger national identity and signalled a tougher stance on groups promoting Islamist extremism.[93] However, official statistics showed that European Union and non-European Union mass immigration, together with asylum seeker applications, all increased substantially during Cameron's term in office.[94][95][96]

Reception

Trade union activist and journalist Jimmy Reid wrote in The Scotsman in 2002 criticising New Labour for failing to promote or deliver equality. He argued that Labour's pursuit of a "dynamic market economy" was a way of continuing the operation of a capitalist market economy which prevented governments from interfering to achieve social justice. Reid argued that the social agenda of Clement Attlee's government was abandoned by Margaret Thatcher and not revived by New Labour. He criticised the party for not preventing inequality from widening and argued that New Labour's ambition to win elections had moved the party towards the right.[97] Many left-wing Labour members such as Arthur Scargill left the party because of New Labour's emergence; however, New Labour attracted many from the centre and centre-right into its ranks. Underlining the significant ideological shifts that had taken place and indicating why the reception of New Labour was negative amongst traditional left-wing supporters, Lord Rothermere, the proprietor of The Daily Mail, defected to the Labour Party, stating: "I joined New Labour because that was obviously the New Conservative party".[98]

Warwick University politics lecturer Stephen Kettell criticised the behaviour of the leadership of New Labour and their use of threats in parliament such as overlooking promotions for MPs in order to maintain party support. While referring to the other parties in Westminster as well, he likened these MPs as "little more than docile lobby-fodder for their respective oligarchies".[99]

Although close to New Labour and a key figure in the development of the Third Way, sociologist Anthony Giddens dissociated himself from many of the interpretations of the Third Way made in the sphere of day-to-day politics. For him, it was not a succumbing to neoliberalism or the dominance of capitalist markets.[100] The point was to get beyond both market fundamentalism and traditional top down socialism—to make the values of the centre-left count in a globalising world. He argued that "the regulation of financial markets is the single most pressing issue in the world economy" and that "global commitment to free trade depends upon effective regulation rather than dispenses with the need for it".[101] In 2002, Giddens listed problems facing the New Labour government, naming spin as the biggest failure because its damage to the party's image was difficult to rebound from. He also challenged the failure of the Millennium Dome project and Labour's inability to deal with irresponsible businesses. Giddens saw Labour's ability to marginalise the Conservative Party as a success as well its economic policy, welfare reform and certain aspects of education. Giddens criticised what he called Labour's "half-way houses", including the National Health Service and environmental and constitutional reform.[102]

See also

References

- "1994: Labour chooses Blair". BBC News. 21 July 1994. Retrieved 18 June 2012.

- Floey 2002, p. 108.

- "Timeline: Blair vs Brown". BBC News. 7 September 2006. Retrieved 15 July 2012.

- Morgan, Kenneth O. (1 October 1998). "The Historical Roots of New Labour". History Today. 48 (10).

- Driver & Martell 2006, p. 13.

- Driver & Martell 2006, pp. 13–14.

- Faucher-King, Florence (2010). The New Labour Experiment: Change and Reform Under Blair and Brown. Stanford: Stanford University Press. p. 88. ISBN 978-0-8047-7621-9. OCLC 719377488.

- Whiteley, P.; Seyd, P. (2003). "How to win a landslide by really trying: the effects of local campaigning on voting in the 1997 British general election". Electoral Studies. 22 (2): 306. doi:10.1016/s0261-3794(02)00017-3. ISSN 0261-3794.

- Barlow & Mortimer 2008, p. 226.

- Else 2009, p. 48.

- Elliot, Faucher-King & Le Galès 2010, p. 65.

- Elliot, Faucher-King & Le Galès 2010, p. 69.

- "The Fabian Society: A Brief History". The Guardian. 13 August 2001. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 24 August 2017.

- Coats & Lawler 2000, p. 296.

- Bérubé 2009, p. 206.

- Lavelle 2008, p. 85.

- Elliot, Faucher-King & Le Galès 2010, p. 123.

- "History of the Labour Party". Labour Party. p. 4. Archived from the original on 25 June 2012. Retrieved 18 June 2012.

- Else 2008, p. 49.

- Morris, Nigel (18 February 2008). "Northern Rock, owned by UK Ltd". The Independent. Archived from the original on 18 June 2022. Retrieved 19 June 2012.

- "Election 2010: First hung parliament in UK for decades". BBC News. 7 May 2010. Retrieved 10 July 2012.

- "Election 2010 National Results". BBC News. Retrieved 10 July 2012.

- "Gordon Brown 'stepping down as Labour leader'". BBC News. 10 May 2010. Retrieved 10 July 2012.

- "Gordon Brown resigns as UK prime minister". BBC News. 11 May 2010. Retrieved 10 July 2012.

- "David Cameron and Nick Clegg pledge 'united' coalition". BBC News. 12 May 2010. Retrieved 10 July 2012.

- "Cameron's government: A guide to who's who". BBC News. 17 October 2010. Retrieved 10 July 2012.

- "David Miliband says New Labour era is over". BBC News. 17 May 2010. Retrieved 10 July 2012.

- Sparrow, Andrew (1 September 2010). "Tony Blair's A Journey memoir released – live blog". The Guardian. Retrieved 15 July 2012.

- Driver 2011, p. 110.

- Curtis, Polly (8 July 2011). "Tony Blair: New Labour died when I handed over to Gordon Brown". The Guardian. Retrieved 21 June 2012.

- Giddens, Anthony (2001). The Global Third Way Debate. Polity Press. ISBN 0745627412.

- Seldon & Hickson 2004, p. 5.

- Daniels & McIlroy 2008, p. 63.

- Colette, Laybourn 2003, p. 91.

- Bevir, Mark (2005). New Labour: A Critique. Abington, Oxon: Routledge. pp. 30–31. ISBN 0-415-35924-4. OCLC 238730608.

- "After Smith: Britain's Labour Party is reeling after the death of its leader. (John Smith) (Editorial)". The Economist. 14 May 1994. Archived from the original on 5 November 2013. Retrieved 2 September 2012 – via HighBeam.

- Heath, Anthony; Jowell, Roger; Curtice, John (1994). Labour's Last Chance?: The 1992 Election and Beyond. Aldershot: Dartmouth. pp. 191–213. ISBN 1-85521-477-6. OCLC 963678831.

- Driver, Stephen (2011). Understanding British Party Politics. Polity Press. pp. 86–87. ISBN 9780745640778. Retrieved 8 May 2016.

- Hattersley, Roy (24 April 1999). "Books: Opportunist in blue socks". The Independent. Archived from the original on 18 June 2022. Retrieved 8 May 2016.

- Hyman, Peter (2005). One Out of Ten: From Downing Street Vision to Classroom Reality. Vintage. p. 48. ISBN 9780099477471. Retrieved 8 May 2016.

- Rentoul, John (15 October 2001). Tony Blair: Prime Minister. Faber and Faber. ISBN 9780571299874. Retrieved 8 May 2016.

- Grice, Andrew (13 May 2005). "Andrew Grice: The Week in Politics". The Independent. Archived from the original on 18 June 2022. Retrieved 8 May 2016.

- Newman & Verčič 2002, p. 51.

- Mattinson, Deborah (15 July 2010). "Talking to a Brick Wall". New Statesman. Retrieved 1 October 2012.

- Newman & Verčič 2002, p. 48.

- Jones, Tudor (1996). Remaking the Labour Party: From Gaitskell to Blair. London: Routledge. pp. 135. ISBN 0-415-12549-9. OCLC 35001797.

- Gaber, Ivor (1998). "The newworld of dogs and lamp-posts". British Journalism Review. 9 (2): 59–65. doi:10.1177/095647489800900210. ISSN 0956-4748. S2CID 144370103.

- Ludlam, Steve; Smith, Martin, J. (2001). Franklin, Bob (ed.). The Hand of History: New Labour, News Management and Governance in 'New Labour in government'. Basingstoke: Palgrave. pp. 133–134. ISBN 0-333-76100-6. OCLC 615213673.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Seldon 2007, p. 125.

- Seldon 2007, pp. 125–126.

- Newman & Verčič 2002, p. 50.

- Kettell 2006, pp. 44–45.

- Faucher-King, Florence; Le Galés, Patrick (2010). The New Labour Experiment: Change and Reform Under Blair and Brown. Stanford: Stanford University Press. p. 91. ISBN 978-0-8047-7621-9. OCLC 719377488.

- Coats & Lawler 2000, pp. 25–26.

- Geddes, Andrew; Tonge, Jonathan (1997). "Labour's Path to Power". In Fielding, Stephen (ed.). Labour's Landslide: The British General Election 1997. Manchester: Manchester University Press. p. 33. ISBN 0-7190-5158-4. OCLC 243568469.

- Coats & Lawler 2000, p. 26.

- Coats & Lawler 2000, pp. 27–28.

- Pattie, Charles; Johnston, Ron; Dorling, Danny; Rossiter, Dave; Tunstall, Helena; MacAllister, Iain (1997). "New Labour, new geography? The electoral geography of the 1997 British General Election". Area. 29 (3): 253–259. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4762.1997.tb00027.x. ISSN 0004-0894.

- Garnett & Lynch 2007, p. 447.

- Pattie, Charles; Johnston, Ron (2001). "A Low Turnout Landslide: Abstention at the British General Election of 1997". Political Studies. 49 (2): 302. doi:10.1111/1467-9248.00314. ISSN 0032-3217. S2CID 143342175.

- Whitely, Paul; Clarke, Harold; Sanders, David; Stewart, Marianne (2001). "Turnout". Britain Votes 2001'. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 215.

- Rubinstein 2006, p. 194.

- Evans, Geoffrey; Curtice, John; Norris, Pippa. "Crest Paper No 64: New Labour, New Tactical Voting? The Causes and Consequences of Tactical Voting in the 1997 General Election". Strathclyde University. Archived from the original on 24 August 1999. Retrieved 17 July 2012.

- Lawson, Neal; Cox, Joe. "New Politics" (PDF). Compass. pp. 4–5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 February 2015. Retrieved 17 July 2012.

- Laybourne 2001, p. 32.

- Foley 2000, p. 315.

- Hale, Leggett & Martell 2004, p. 87.

- Laybourne 2001, pp. 44–45.

- Laybourne 2001, p. 45.

- Driver 2011, p. 94

- Tunney 2007, p. 83.

- Laybourn 2001, p. 34.

- Fairclough 2000, p. 1.

- Pogrund, Caroline Wheeler, Gabriel. "Starmer calls in Mandelson to inject a dose of New Labour's 'winning mentality'". The Times. ISSN 0140-0460. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Tunney 2007, p. 113.

- Kramp 2010, p. 4.

- Driver 2011, p. 108.

- Vincent 2009, p. 93.

- Adams 1998, p. 140.

- Powell 2002, p. 22.

- Rubinstein 2006, p. 185.

- Beech, Matt; Lee, Simon (2008). "New Labour and Social Policy". In Driver, Stephen (ed.). Ten years of New Labour. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 52. ISBN 978-0-230-57442-7. OCLC 938615080.

- Annesley, Claire; Ludlam, Steve; Smith, Martin J. (2004). "Economic and Welfare Policy". In Gamble, Andrew (ed.). Governing as New Labour: Policy and Politics Under Blair. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 147. ISBN 1-4039-0474-X. OCLC 464870552.

- Gower, Chris (22 March 2003). "'New Labour', welfare reform and the reserve army of labour. (Behind the News)". Capital & Class: 17. Retrieved 14 July 2012.

- "From the archive: Tony Blair is tough on crime, tough on the causes of crime". www.newstatesman.com. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- Bochel & Defty 2007, p. 23.

- Squires 2008, p. 135.

- Cohen, Nick (30 July 2011). "Welcome to Britain, a breeding ground for talking hate". The Guardian. Retrieved 21 June 2019.

- Neather, Andrew (23 October 2009). "Don't listen to the whingers – London needs immigrants". London Evening Standard. Retrieved 29 September 2013.

- Whitehead, Tom (23 October 2009). "Labour wanted mass immigration to make UK more multicultural, says former adviser". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 29 September 2013.

- Neather, Andrew (26 October 2009). "How I became the story and why the Right is wrong". Archived from the original on 2 December 2009.

- Kirkup, James. "Muslims must embrace our British values, David Cameron says". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 7 February 2011. Retrieved 1 February 2012.

- Kuenssberg, Laura (5 February 2011). "State multiculturalism has failed, says David Cameron". BBC News. Retrieved 1 February 2012.

- Maclellan, Kylie (25 February 2016). "As EU vote looms, immigration rise piles pressure on Cameron". reuters.com.

- William James (27 August 2015). "UK immigration hits record high, causing headache for Cameron". reuters.com.

- Grice, Andrew (26 February 2015). "David Cameron immigration pledge 'failed spectacularly' as figures show net migration almost three times as high as Tories promised". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 18 June 2022.

- Reid, Jimmy (21 October 2002). "The word that is missing from the New Language of New Labour". The Scotsman. Retrieved 13 June 2017.

- Jefferys, Kevin (1999). Rentoul, John (ed.). Leading Labour: From Keir Hardie to Tony Blair. London: Tauris. p. 209. ISBN 1-86064-453-8. OCLC 247671633.

- Kettell, Steven (2006). Dirty Politics?: New Labour, British Democracy and the Invasion of Iraq. London: Zed. p. 17. ISBN 1-84277-740-8. OCLC 62344728.

- Giddens, Anthony (2000). The Third Way and its Critics. Polity Press, p. 32. ISBN 0-74562450-2.

- Giddens, Anthony (1998). The Third Way; A Renewal of Social Democracy. Polity Press, pp. 148–49. ISBN 0-74562266-6.

- Grice, Andrew (7 January 2002). "Architect of 'Third Way' attacks New Labour's policy 'failures'". The Independent. Archived from the original on 18 June 2022. Retrieved 13 June 2017.

Bibliography

- Adams, Ian (1998). Ideology and Politics in Britain Today. Manchester University Press. ISBN 9780719050565.

- Paul Anderson and Nyta Mann (1997). Safety First: The Making of New Labour. Granta. ISBN 1862070709.

- Barlow, Keith; Mortimer, Jim (2008). The Labour Movement in Britain from Thatcher to Blair. Peter Lang. ISBN 9783631551370.

- Bérubé, Michael (2009). The Left at War. NYU Press. ISBN 9780814799840.

- Bevir, Mark (6 December 2012). New Labour: A Critique. Routledge. ISBN 9781134241750.

- Bochel, Hugh; Defty, Andrew (2007). Welfare Policy Under New Labour: Views from Inside Westminster. The Policy Press. ISBN 9781861347909.

- Coats, David; Lawler, Peter (2000). New Labour in Power. Manchester University Press. ISBN 9780719054624.

- Collette, Christine; Laybourn, Keith (2003). Modern Britain Since 1979: A Reader. I. B. Tauris. ISBN 9781860645976.

- Coulter, Steve (2014). New Labour Policy, Industrial Relations and the Trade Unions. Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1057/9781137495754. ISBN 978-1-349-50496-1.

- Curtice, John; Heath, Anthony; Jowell, Roger (2001). The Rise of New Labour: Party Policies and Voter Choices. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780191529641.

- Daniels, Gary; McIlroy, John (2008). Trade Unions in a Neoliberal World: British Trade Unions Under New Labour. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9780203887738.

- Diamond, Patrick. New Labour's Old Roots (Andrews UK Limited, 2015).

- Driver, Stephen; Martell, Luke (2006). New Labour. Polity. ISBN 9780745633312.

- Driver, Stephen (2011). Understanding British Party Politics. Polity. ISBN 9780745640778.

- Else, David (2009). England. Lonely Planet. ISBN 9781741045901.

- Elliot, Gregory; Florence, Faucher-King; Le Galès, Patrick (2010). The New Labour Experiment: Change and Reform Under Blair and Brown. Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804762359.

- Fairclough, Norman (2000). New Labour, New Language?. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9780415218276.

- Faucher-King, Florence, and Patrick Le Gales, eds. The New Labour experiment: change and reform under Blair and Brown (Stanford UP, 2010).

- Fielding, Steven (2004). "The 1974-9 Governments and 'New' Labour". In Seldon, Anthony; Hickson, Kevin (eds.). New Labour, Old Labour: The Wilson and Callaghan Governments 1974–1979. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-41531-281-3.

- Foley, Michael (2000). The British Presidency: Tony Blair and the Politics of Public Leadership. Manchester University Press. ISBN 9780719050169.

- Foley, Michael (2002). John Major, Tony Blair and a Conflict of Leadership: Collision Course. Manchester University Press. ISBN 9780719063176.

- Garnett, Philip; Lynch (2007). Exploring British Politics. Pearson Education. ISBN 9780582894310.

- Hale, Sarah; Leggett, Will; Martell, Luke (2004). The Third Way and Beyond: Criticisms, Futures and Alternatives. Manchester University Press. ISBN 9780719065996.

- Hickson, Kevin; Seldon, Anthony (2004). New Labour, Old Labour: The Wilson and Callaghan Governments, 1974–79. Psychology Press. ISBN 9780415312820.

- Kettel, Steven (2006). Dirty Politics?: New Labour, British Democracy and the Invasion of Iraq. Zed Books. ISBN 9781842777411.

- Kramp, Philipp (2010). The British Labour Party and the "Third Way": Analysing the Ideological Change and Its Reasons Under the Leadership of Tony Blair. GRIN Verlag. ISBN 9783640750337.

- Laybourne, Keith (2001). British Political Leaders: A Biographical Dictionary. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781576070437.

- Laybourne, Keith (2002). Fifty Key Figures in Twentieth-century British Politics. Routledge. ISBN 9780415226769.

- Lees-Marshment, Jennifer (2009). Political Marketing: Principles and Applications. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9780415431286.

- Minkin, Lewis. The Blair Supremacy: A Study in the Politics of Labour's Party Management (Manchester University Press, 2014).

- Newman, Bruce; Verčič, Dejan (2002). Communication of Politics: Cross-Cultural Theory Building in the Practice of Public Relations and Political Marketing. Routledge. ISBN 9780789021595.

- Powell, Martin (1999). New Labour, New Welfare State?: The "Third Way" in British Social Policy. The Policy Press. ISBN 9781861341518.

- Rawnsley, Andrew. The End of the Party: The Rise and Fall of New Labour (Penguin, 2010).

- Powell, Martin (2002). Evaluating New Labour's Welfare Reforms. The Policy Press. ISBN 9781861343352.

- Rubinstein, David (2006). The Labour Party and British Society: 1880–2005. Sussex Academic Press. ISBN 9781845190569.

- Seldon, Anthony (2007). Blair's Britain, 1997–2007. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521882934.

- Tunney, Sean (2007). Labour and The Press: From New Left to New Labour. Sussex Academic Press. ISBN 9781845191382.

- Squires, Peter (2008). Asbo Nation: The Criminalisation of Nuisance. The Policy Press. ISBN 9781847420275.

- Vincent, Andrew (2009). Modern Political Ideologies. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781405154956.

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.svg.png.webp)