Northumberland House

Northumberland House (also known as Suffolk House when owned by the Earls of Suffolk) was a large Jacobean townhouse in London, so-called because it was, for most of its history, the London residence of the Percy family, who were the Earls and later Dukes of Northumberland and one of England's richest and most prominent aristocratic dynasties for many centuries. It stood at the far western end of the Strand from around 1605 until it was demolished in 1874. In its later years it overlooked Trafalgar Square.

.JPG.webp)

Background

In the 16th century the Strand, which connects the City of London with the royal centre of Westminster, was lined with the mansions of some of England's richest prelates and noblemen. Most of the grandest houses were on the southern side of the road and had gardens stretching down to the River Thames e.g. Durham House.[2]

Construction

In around 1605 Henry Howard, 1st Earl of Northampton cleared a site at Charing Cross[3] on the site of a convent[4] and built himself a mansion, at first known as Northampton House. The Strand facade was 162 feet (49 m) wide and the house's depth was marginally greater. It had a single central courtyard and turrets in each corner.[5]

The balustrade of the Strand front carried an inscription in stone letters.[6] During the funeral of Anne of Denmark in May 1619, a large stone letter 'S' fell from the façade onto spectators of the procession, killing one William Appleyard.[7] According to Nathaniel Brent, the stone was part of a motto and was "thrust down by a gentlewoman who put her foot against it, not thinking it had been so brickle [brittle]".[8]

The garden was 160 feet (49 m) wide and over 300 feet (91 m) long, but unlike those of neighbouring mansions to the east, it did not reach all the way down to the river.[9]

Seventeenth and eighteenth centuries

The house passed from Lord Northampton to the Earls of Suffolk, another branch of the powerful Howard family headed by the Dukes of Norfolk. In the 1640s it was sold to the Earl of Northumberland, at the discounted price of £15,000, as part of the marriage settlement when he married a Howard.[10]

Regular alterations were made over the next two centuries in response to fashion and to make the layout more convenient for the lifestyle of the day. John Webb was employed from 1657 to 1660 to relocate the family's living accommodation from the Strand front to the garden front. In the 1740s and 1750s the Strand front was largely reconstructed and two wings were added which projected from the ends of the garden front at right angles. These were over 100 feet (30 m) long, in late palladian style, and contained a ballroom and a picture gallery, the latter itself 106 feet (32 m) long. The architects were Daniel Garrett, until his death in 1753; and then the better known James Paine. In the mid-1760s Robert Mylne was employed to reface the courtyard in stone; he may also have been responsible for extensions to the two garden wings which were made at that time. In the 1770s Robert Adam was commissioned to redecorate the state rooms on the garden front, and the Glass Drawing Room at Northumberland House was one of his most celebrated interiors. Part of the Strand front had to be rebuilt after a fire in 1780.[10]

Nineteenth century

In 1819 Thomas Cundy was employed to rebuild the Garden (South) Front, which had become unstable, moving it 5 feet (1.5 m) south; he subsequently added the final main staircase.[10]

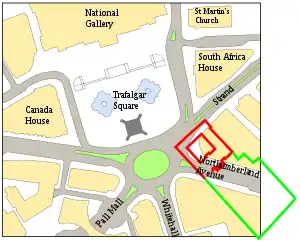

By the end of the mid-19th century the other mansions on the Strand had been demolished. The area was largely commercial and its entertainment industry had grown, meaning it was no longer a fashionable place for aristocracy to live. The then Duke of Northumberland was reluctant to leave his generations-held home, although he was pressured to do so by the Metropolitan Board of Works, which wished to build a road through the middle of the site to connect to the new roads by the Embankment. After a fire which caused substantial damage, the Duke accepted an offer of £500,000 in 1874 (equivalent to £49,400,000 in 2021). Northumberland House was demolished and Northumberland Avenue, including its buildings fronting, was built in its place.[10]

Northumberland Avenue

.jpg.webp)

One of the largest buildings on the newly built Northumberland Avenue was the 500-bedroom Hotel Victoria, which in its arched entrance, and oriel window above it, imitated Northumberland House. During the Second World War it was taken over by the Ministry of Defence and renamed Northumberland House. It is now known as No. 8 Northumberland Avenue.[11]

Remains

An archway from Northumberland House, designed by William Kent, was sold for the entrance to the garden of Tudor House, which formerly stood in Bromley-by-Bow. It was moved in 1998 to form the principal entrance to the Bromley by Bow Centre.[12] A section of the panelling from the 1770s glass drawing room survives in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum.[13]

See also

- Alnwick Castle – the Percy family's main seat.

- List of demolished buildings and structures in London

- Syon House – the Percy family's west London residence.

Notes, references and sources

- Notes and references

- Per inscribed tablet at Syon House, see File:Percy Lion plaque.jpg

- "Durham House". Royal Palaces. Retrieved 5 March 2021.

- The site was the eastern portion of the former property of the Chapel and Hospital of St Mary Rounceval.

- Hibbert, Christopher; Ben Weinreb; John Keay; Julia Keay (2010). The London Encyclopaedia. London: Pan Macmillan. p. 593. ISBN 978-0-230-73878-2.

- The Strand front of Northumberland House in 1752 by Canaletto.

- Manolo Guerci, London's Golden Mile: The Great Houses of the Strand (Yale, 2021), pp. 203-4, 216.

- Thomas Mason, A register of baptisms, marriages, and burials in the parish of St. Martin in the Fields (London, 1898), p. 179

- Norman MacClure, Letters of John Chamberlain, vol. 2 (Philadelphia, 1932), p. 237: Mary Anne Everett Green, CSP. Domestic, 1619-1623, p. 45 citing TNA SP14/109 f.77.

- John Rocque's Map of London, 1746

- Gater, G. H.; Wheeler, E. P. (1937). "'Northumberland House', in Survey of London: Volume 18, St Martin-in-The-Fields II: the Strand". London: British History Online. pp. 10–20. Retrieved 5 March 2021.

- "Our history". No. 8 Northumberland Avenue. Retrieved 5 March 2021.

- "Bromley-by-Bow and Three Mills Island" (PDF). Walk East. Retrieved 5 March 2021.

- "Glass Drawing Room". vam.ac.uk. Victoria and Albert Museum. 5 March 1999. Retrieved 12 October 2023.

- Sources

- London's Mansions David Pearce (BT Batsford Ltd., 1986) ISBN 0-7134-8702-X

External links

- Northumberland House at the Survey of London online

- Northumberland House and its associations – section of Old and New London Volume 3 (1878)