Northern Epirus

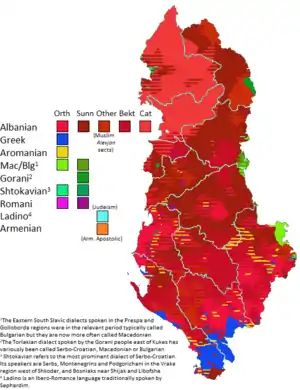

Northern Epirus (Greek: Βόρεια Ήπειρος, Vória Ípiros; Albanian: Epiri i Veriut; Aromanian: Epiru di Nsusu) is a term used to refer to those parts of the historical region of Epirus, in the western Balkans, which today are part of Albania. The term is used mostly by Greeks and is associated with the existence of a substantial ethnic Greek minority in the region.[lower-alpha 1] It also has connotations with irredentist political claims on the territory on the grounds that it was held by Greece and in 1914 was declared an independent state[2] by the local Greeks against annexation to the newly founded Albanian principality.[lower-alpha 2] The term is typically rejected by most Albanians for its irredentist associations.

Northern Epirus

| |

|---|---|

Territory claimed as part of Northern Epirus | |

| Present status | Albania |

| Biggest city | Gjirokastër |

| Other cities | |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| ISO 3166 code | AL |

It started to be used by Greeks in 1913, upon the creation of the Albanian state following the Balkan Wars, and the incorporation into the latter of territory that was regarded by many Greeks as geographically, historically, culturally, and ethnologically connected to the Greek region of Epirus since antiquity.[lower-alpha 3] In the spring of 1914, the Autonomous Republic of Northern Epirus was proclaimed by ethnic Greeks in the territory and recognized by the Albanian government, though it proved short-lived as Albania collapsed with the onset of World War I. Greece held the area between 1914 and 1916 and unsuccessfully tried to annex it in March 1916.[lower-alpha 3] In 1917 Greek forces were driven from the area by Italy, who took over most of Albania.[5] The Paris Peace Conference of 1919 awarded the area to Greece, however the area reverted to Albanian control in November 1921, following Greece's defeat in the Greco-Turkish War.[6] During the interwar period, tensions remained high due to the educational issues surrounding the Greek minority in Albania.[lower-alpha 3] Following Italy's invasion of Greece from the territory of Albania in 1940 and the successful Greek counterattack, the Greek army briefly held Northern Epirus for a six-month period until the German invasion of Greece in 1941.

Tensions remained high during the Cold War, as the Greek minority was subjected to repressive measures (along with the rest of the country's population). Although a Greek minority was recognized by the Hoxha regime, this recognition only applied to an "official minority zone" consisting of 99 villages, leaving out important areas of Greek settlement, such as Himara. People outside the official minority zone received no education in the Greek language, which was prohibited in public. The Hoxha regime also diluted the ethnic demographics of the region by relocating Greeks living there and settling in their stead Albanians from other parts of the country.[lower-alpha 3] Relations began to improve in the 1980s with Greece's abandonment of any territorial claims over Northern Epirus and the lifting of the official state of war between the two countries.[lower-alpha 3] In the post Cold War era relations have continued to improve though tensions remain over the availability of education in the Greek language outside the official minority zone, property rights, and occasional violent incidents targeting members of the Greek minority.

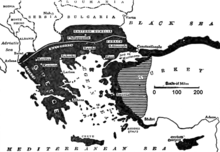

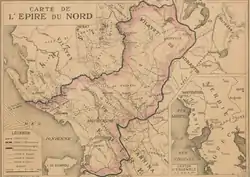

Name and definition

The Greek toponym Epirus (Greek: Ήπειρος), meaning "mainland" or "continent", first appears in the work of Hecataeus of Miletus in the 6th century BC and is one of the few Greek names from the view of an external observer with a maritime-geographical perspective. Although not originally a native Epirote name, it later came to be adopted by the inhabitants of the area.[7] The term Epirus is used both in the Albanian and Greek language, but in Albanian refers only to the historical and not the modern region. The term Northern Epirus rather than a clearly defined geographical term, is largely a political and diplomatic term applied to those areas partly populated by ethnic Greeks that were incorporated into the newly independent Albanian state in 1913.[lower-alpha 3] The term "Northern Epirus" was first used in official Greek correspondence in 1886, to describe the northern parts of the Janina Vilayet.[lower-alpha 4] According to the 20th century definition, Northern Epirus stretches from the Ceraunian Mountains north of Himara southward to the Greek border, and from the Ionian coast to Lake Prespa. Some of the cities and towns of the region are: Himarë, Sarandë, Delvinë, Gjirokastër, Korçë, and the once prosperous town of Moscopole. The region defined as Northern Epirus thus stretches further east than classical Epirus, and includes parts of the historical region Macedonia. The main rivers of the area are: Vjosë/Aoos (Greek: Αώος, Aoos) its tributary the Drino (Greek: Δρίνος, Drinos), the Osum (Greek: Άψος Apsos) and the Devoll (Greek: Εορδαϊκός Eordaikos).

In antiquity, the northern border of the historical region of Epirus (and of the ancient Greek world) was the Gulf of Oricum,[9] [10][11] or alternatively, the mouth of the Aoös river, immediately to the north of the Bay of Aulon (modern-day Vlorë).[lower-alpha 5] The northern boundary of Epirus was unclear both due to political instability and the coexistence of Greek and non-Greek populations, notably Illyrians, such as in Apollonia.[13] From the 4th century BCE onward, with a degree of certainty, the boundaries of Epirus included the Ceraunian mountains in the north, the Pindus mountains in the east, the Ionian Sea in the West, and the Ambracian Gulf in the south.[13]

History

Ottoman period

.jpg.webp)

The local Ottoman authority was mainly exercised by Muslim Albanians.[14] There were specific parts of Epirus that enjoyed local autonomy, such as Himarë, Droviani, or Moscopole. In spite of the Ottoman presence, Christianity prevailed in many areas and became an important reason for preserving the Greek language, which was also the language of trade.[15][16] Between the 16th and 19th centuries, inhabitants of the region participated in the Greek Enlightenment. One of the leading figures of that period, the Orthodox missionary Cosmas of Aetolia, traveled and preached extensively in northern Epirus, founding the Acroceraunian School in Himara in 1770. It is believed that he founded more than 200 Greek schools until his execution by Turkish authorities near Berat.[17] In addition, the Moscopole printing house, the first in the Balkans after that of Constantinople, was founded in Moscopole.[18] From the mid-18th century trade in the region was thriving and a great number of educational facilities and institutions were founded throughout the rural regions and the major urban centers as benefactions by several Epirot entrepreneurs.[19] In Korçë a special community fund was established that aimed at the foundation of Greek cultural institutions.[20]

During this period a number of uprisings against the Ottoman Empire periodically broke out. In the Orlov Revolt (1770) several units of Riziotes, Chormovites and Himariotes supported the armed operation. Some Greeks from the area took also part in the Greek War of Independence (1821–1830): many locals revolted, organized armed groups and joined the revolution.[21] The most distinguished personalities were the engineer Konstantinos Lagoumitzis[22] from Hormovo and Spyromilios from Himarë. The latter was one of the most active generals of the revolutionaries and participated in several major armed conflicts, such as the Third Siege of Missolonghi, where Lagoumitzis was the defenders' chief engineer. Spyromilios also became a prominent political figure after the creation of the modern Greek state and discreetly supported the revolt of his compatriots in Ottoman-occupied Epirus in 1854.[23] Another uprising in 1878, in the Saranda-Delvina region, with the revolutionaries demanding union with Greece, was suppressed by the Ottoman forces, while in 1881, the Treaty of Berlin awarded to Greece the southernmost parts of Epirus.

According to the Ottoman "Millet" system, religion was a major marker of ethnicity, and thus all Orthodox Christians (Greeks, Aromanians, Orthodox Albanians, Slavs etc.) were classified as "Greeks", while all Muslims (including Muslim Albanians, Greeks, Slavs etc.) were considered "Turks".[24] The dominant view in Greece considers Orthodox Christianity an integral element of the Hellenic heritage, as part of its Byzantine past.[lower-alpha 6] Thus, official Greek government policy from c. 1850 to c. 1950, adopted the view that speech was not a decisive factor for the establishment of a Greek national identity.[lower-alpha 7]

Balkan Wars (1912–13)

With the outbreak of the First Balkan War (1912–13) and the Ottoman defeat, the Greek army entered the region. The outcome of the following Peace Treaties of London[lower-alpha 8] and of Bucharest,[lower-alpha 9] signed at the end of the Second Balkan War, was unpopular among both Greeks and Albanians, as settlements of the two people existed on both sides of the border: the southern part of Epirus was ceded to Greece, while Northern Epirus, already under the control of the Greek army, was awarded to the newly found Albanian State. However, due to the late emergence and fluidity of Albanian national identity and an absence of religious Albanian institutions, loyalty in Northern Epirus especially amongst the Orthodox to potential Albanian rule headed by (Albanian) Muslim leaders was not guaranteed.[lower-alpha 10]

Autonomous Republic of Northern Epirus (1914)

In accordance with the wishes of the local Greek population, the Autonomous Republic of Northern Epirus, centered in Gjirokastër on account of the latter's large Greek population,[30] was declared in March 1914 by the pro-Greek party, which was in power in southern Albania at that time.[31] Georgios Christakis-Zografos, a distinguished Greek politician from Lunxhëri, took the initiative and became the head of the Republic.[31] Fighting broke out in Northern Epirus between Greek irregulars and Muslim Albanians who opposed the Northern Epirot movement.[lower-alpha 11] In May, autonomy was confirmed with the Protocol of Corfu, signed by Albanian and Northern Epirote representatives and approved by the Great Powers. The signing of the Protocol ensured that the region would have its own administration, recognized the rights of the local Greeks and provided self-government under nominal Albanian sovereignty.[31]

However, the agreement was never fully implemented, because when World War I broke out in July, Albania collapsed. Although short-lived,[31][lower-alpha 12] the Autonomous Republic of Northern Epirus left behind a substantial historical record, such as its own postage stamps.

World War I and following peace treaties (1914–21)

Under an October 1914 agreement among the Allies,[34] Greek forces re-entered Northern Epirus and the Italians seized the Vlore region.[31] Greece officially annexed Northern Epirus in March 1916, but was forced to revoke by the Great Powers.[lower-alpha 3] During the war the French Army occupied the area around Korçë in 1916, and established the Republic of Korçë. In 1917 Greece lost control of the rest of Northern Epirus to Italy, who by then had taken over most of Albania.[5] The Paris Peace Conference of 1919 awarded the area to Greece after World War I, however, political developments such as the Greek defeat in the Greco-Turkish War (1919–22) and, crucially, Italian, Austrian and German lobbying in favor of Albania resulted in the area being ceded to Albania in November 1921.[6]

Interwar period (1921–39) - Zog's regime

The Albanian Government, with the country's entrance to the League of Nations (October 1921), made the commitment to respect the social, educational, religious rights of every minority.[35] Questions arose over the size of the Greek minority, with the Albanian government claiming 16,000, and the League of Nations estimating it at 35,000-40,000.[lower-alpha 3] In the event, only a limited area in the Districts of Gjirokastër, Sarandë and four villages in Himarë region consisting of 15,000 inhabitants[36] was recognized as a Greek minority zone.

The following years, measures were taken to suppress[lower-alpha 13] the minority's education. The Albanian state viewed Greek education as a potential threat to its territorial integrity,[36] while most of the teaching staff was considered suspicious and in favour for the Northern Epirus movement.[lower-alpha 14] In October 1921, the Albanian government recognised minority rights and legalised Greek schools only in Greek speaking settlements located within the "recognised minority zone".[lower-alpha 15][lower-alpha 16] Within the rest of the country, Greek schools were either closed or forcibly converted to Albanian schools and teachers were expelled from the country.[lower-alpha 15][lower-alpha 16] During the mid-1920s, attempts at opening Greek schools and teacher training colleges in urban areas with sizable Greek populations were met with difficulties which resulted in an absence of urban Greek schools in coming years.[lower-alpha 17][lower-alpha 18] With the intervention of the League of Nations in 1935, a limited number of schools, and only of those inside the officially recognized zone, were reopened. The 360 schools of the pre-World War I period were reduced dramatically in the following years and education in Greek was finally eliminated altogether in 1935:[lower-alpha 19][45]

1926: 78, 1927: 68, 1928: 66, 1929: 60, 1930: 63, 1931: 64, 1932: 43, 1933: 10, 1934: 0

During this period, the Albanian state led efforts to establish an independent orthodox church (contrary to the Protocol of Corfu), thereby reducing the influence of Greek language in the country's south. According to a 1923 law, priests who were not Albanian speakers, as well as not of Albanian origin, were excluded from this new autocephalous church.[36]

World War II (1939–45)

In 1939, Albania became an Italian protectorate and was used to facilitate military operations against Greece the following year. The Italian attack, launched at October 28, 1940 was quickly repelled by the Greek forces. The Greek army, although facing a numerically and technologically superior army, counterattacked and in the next month managed to enter Northern Epirus. Northern Epirus thus became the site of the first clear setback for the Axis powers. However, after a six-month period of Greek administration, the invasion of Greece by Nazi Germany followed in April 1941 and Greece capitulated.[46]

Following Greece's surrender, Northern Epirus again became part of the Italian-occupied Albanian protectorate. Many Northern Epirotes formed resistance groups and organizations in the struggle against the occupation forces. In 1942 the Northern Epirote Liberation Organization (EAOVI, also called MAVI) was formed.[47] Some others, c. 1,500 joined the left-wing Albanian National Liberation Army, in which they formed three separate battalion (named Thanasis Zikos, Pantelis Botsaris, Lefteris Talios).[48][49][50] During the latter stages of the war, the Albanian communists were able to stop contact between the minority and the right-wing soldiers of EDES in southern Epirus, that wanted to unite Northern Epirus with Greece .[48]

When the war ended and the communists gained power in Albania, a United States Senate resolution demanded the cession of the region to the Greek state, but according to the following post war international peace treaties it remained part of the Albanian state.[51] During this time, some Greeks and Orthodox Albanians managed to flee Albania and resettle in Greece.[lower-alpha 20]

Cold War period (1946–91) - Hoxha's regime

At the end of World War II, normal relations between Greece and Albania were not restored, and the two countries remained technically in a state of war until 1987. This was largely due to Greece's territorial claims on Northern Epirus and the treatment of the Greek minority. Relations remained tense for most of the Cold War as a result.[54]

Enver Hoxha was willing to build a constituency with the Greek minority since 1944, while some minority members had participated in the partisan struggle against the Axis.[55] A policy of tokenism was adopted with a few favoured members of the Greek minority taking prominent positions in the one-party system.[56]

After WWII, Albania restored the minority zone based on the 1921 League of Nations agreement but without the inclusion of the three Himara villages and education in Greek within the minority zone along with other competencies based on Comintern policies on cultural-linguistic minority issues. These competencies were related to territorial rights - as in the Soviet Union - and didn't apply as individual rights outside the minority zones. Further issues about their application involved local politics which concerned the participation of specific communities in Communist units during WWII. After the regime's end in 1990–91, the application of this system for the Greek minority has been described by sharply diverging narratives. Greeks in Albania, unlike minorities in other countries of the Balkans like Slav-Macedonians in Greece during this era, were a formally recognized minority which had the right to education in Greek as well as the right to publish and broadcast in Greek.[57] Nevertheless, the use of Greek outside the minority zones, for example in Himara, was forbidden, and many Greek names of people and places were changed to Albanian.[58]

The Soviet-Yugoslav rapprochement in the early 1960s and the possibility that Greece might annex Northern Epirus were important factors in Albania's rift with the Soviet Union and its move towards China.[59] In 1967, all religious places of worship in the country were closed, all forms of public worship were outlawed throughout the country, and the existence of an Orthodox Christian population in Northern Epirus was officially denied. These measures were particularly harsh for the Epirote minority, since their religion was tied to their culture.[60] As part of the atheism campaign the Greek minority was subject to much more comprehensive persecusion, with the closure and demolition of churches, burning of religious books and widespread human rights violations.[61] Approximately 630 Orthodox churches in southern Albania were either closed or re-purposed. In 1975, "foreign" or religious personal and place names were prohibited, and had to change.[60]

The regime also relocated Albanian settlers to the Greek minority regions and at the same time forced many Greeks to relocate to northern and central Albania, in what was seen by ethnic Greeks as an attempt to alter the demographic composition of Northern Epirus.[58][62] In the "minority zones", the regime created new villages with Albanian settlers, or else settled Albanian families in villages that had previously been entirely Greek. In the mixed villages, the minority rights of the Greek inhabitants were curtailed. The settlers were frequently military or administrative personnel and their families, and acted as enforcers of regime policies. Examples of these policies was the settling of 300 Albanian families in the Greek-inhabited town of Himara, and the creation of an entirely new settlement of Gjashta, comprised 3,000 Cham Albanians in the vicinity of Saranda. The settlers were awarded land grants, resulting in the permanent alteration of the demographic composition of these areas.[63]

The first serious attempt to improve relations was initiated by Greece in the 1980s, during the government of Andreas Papandreou.[lower-alpha 3] In 1984, during a speech in Epirus, Papandreou declared that the inviolability of European borders as stipulated in the Helsinki Final Act of 1975, to which Greece was a signatory, applied to the Greek-Albanian border.[lower-alpha 3] The most significant change occurred on 28 August 1987, when the Greek Cabinet lifted the state of war that had been declared since November 1940.[lower-alpha 3] At the same time, Papandreou deplored the "miserable condition under which the Greeks in Albania live".[lower-alpha 3] As Albania became more dependent on trade relations with Greece the situation of the ethnic Greek population gradually improved, but nevertheless discriminatory practices existed at the time of the collapse of the People's Republic of Albania (1990).[64] During the years of the communist regime, irredentist aspirations by the pro-Greek parties of southern Albania was nonexistent, but re-emerged after the regime's collapse in 1991.[58]

Post-communist period (1991-present)

Beginning in 1990, large number of Albanian citizens, including members of the Greek minority, began seeking refuge in Greece. This exodus turned into a flood by 1991, creating a new reality in Greek-Albanian relations.[lower-alpha 3] With the fall of communism in 1991, Orthodox churches were reopened and religious practices were permitted after 35 years of strict prohibition. Moreover, Greek-language education was initially expanded. In 1991 ethnic Greeks shops in the town of Saranda were attacked, and inter-ethnic relations throughout Albania worsened.[49][lower-alpha 21] Greek-Albanian tensions escalated in November 1993 when seven Greek schools were forcibly closed by the Albanian police.[66] A purge of ethnic Greeks in the professions in Albania continued in 1994, with particular emphasis in law and the military.[67]

Trial of the Omonoia Five

Tensions increased when on 20 May 1994 the Albanian Government took into custody five members of the ethnic Greek advocacy organization Omonoia on the charge of high treason, accusing them of secessionist activities and illegal possession of weapons (a sixth member was added later).[lower-alpha 22] Sentences of six to eight years were handed down. The accusations, the manner in which the trial was conducted and its outcome were strongly criticized by Greece as well as international organizations. Greece responded by freezing all EU aid to Albania, sealing its border with Albania, and between August–November 1994, expelling over 115,000 illegal Albanian immigrants, a figure quoted in the US Department of State Human Rights Report and given to the American authorities by their Greek counterpart.[69] Tensions increased even further when the Albanian government drafted a law requiring the head of the Orthodox Church in Albania be born in Albania, which would force the then head of the church, the Greek Archbishop Anastasios of Albania from his post.[lower-alpha 3] In December 1994, however, Greece began to permit limited EU aid to Albania as a gesture of goodwill, while Albania released two of the Omonoia defendants and reduced the sentences of the remaining four. In 1995, the remaining defendants were released on suspended sentences.[lower-alpha 3]

Recent years

In recent years relations have significantly improved; Greece and Albania signed a Friendship, Cooperation, Good Neighborliness and Security Agreement on March 21, 1996.[lower-alpha 3]

Although relations between Albania and Greece have greatly improved in recent years, the Greek minority in Albania continues to suffer discrimination particularly regarding education in the Greek language,[lower-alpha 3] property rights of the minority, and violent incidents against the minority by nationalist extremists. Tensions resurfaced during local government elections in Himara in 2000, when a number of incidents of hostility towards the Greek minority took place, as well as with the defacing of signposts written in Greek in the country's south by Albanian nationalist elements,[70] and more recently following the death of Aristotelis Goumas. There were tensions as international talks on Kosovo's independence got underway in 2007, and there were also incidents following the 2008 Kosovo declaration of independence.[71][72] Tensions rose again following the 2014 administrative and territorial reform in Albania; and again in 2016 and 2017, following the decision of local authorities in Himara to demolish the homes of 19 ethnic Greek families.[73]

Demographics

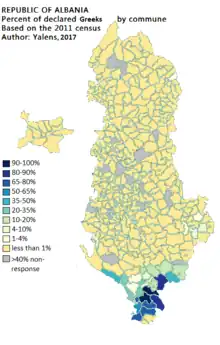

In Albania, Greeks are considered a "national minority". There were no reliable statistics on the size of any ethnic minorities,[lower-alpha 23] while the latest official census (2011) has been widely disputed due to boycott and irregularities in the procedure.[75][76][77]

In general Albania and Greece hold different and often conflicting estimations, as they have done so for the last 20 years.[78] According to data presented to the 1919 Paris Conference, by the Greek side, the Greek minority numbered 120,000,[79] but a CIA report of 1948 put the number at 35,000.[80] The 1989 census under the communist regime cited 58,785 Greeks,[79] while estimations by the Albanian government during the early 1990s raised the number to 80,000.[81]

Most non-Albanian sources have placed the number of ethnic Greeks in Albania, including those who have moved to live in Greece, to be approximately 200,000, while Greek sources claim that there are around 300,000 ethnic Greeks in Albania.[82] As Albanians and Greeks hold different views on what constitutes a Greek in Albania, the total number fluctuates greatly which explains the inconsistent totals provided within Albania and Greece and from external agencies, organisations and sources. Community groups representing Albania's Greeks in Greece have given a 286,000 sum.[83] Furthermore, the Migration Policy Institute has noted that 189,000 Albanian immigrants of Greek ancestry live in Greece as 'co-ethnics', a title reserved for Albania's Greek community members.[84]

However, the area studied was confined to the southern border, and this estimate is considered to be low. Under this definition, minority status was limited to those who lived in 99 villages in the southern border areas, thereby excluding important concentrations of Greek settlement and making the minority seem smaller than it is.[lower-alpha 23] Sources from the Greek minority have claimed that there are up to 400,000 Greeks in Albania, or 12% of the total population at the time (from the "Epirot lobby" of Greeks with family roots in Albania).[85] According to Ian Jeffries in 1993, most western estimates of the minority's size put it at around 200,000, or ~6% of the population,[86] though a large number, possibly two thirds, has migrated to Greece in recent years.[lower-alpha 3]

The Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization estimates the Greek minority at approximately 70,000 people.[87] Other independent sources estimate that the number of Greeks in Northern Epirus is 117,000 (about 3.5% of the total population),[88] a figure close to the estimate provided by The World Factbook (2006) (about 3%). But this number was 8% by the same agency a year before.[89][90] The 2014 CIA World Factbook estimate put the Greek minority at 0.9%, which is based on the disputed 2011 census.[91] A 2003 survey conducted by Greek scholars estimate the size of the Greek minority at around 60.000.[92] The US State Department uses a 1.17% figure for Greeks in Albania.[93] In addition an estimated of 189,000 ethnic Greeks who are Albanian citizens reside in Greece.[lower-alpha 24]

The Greek minority in Albania is located compactly, within the wider Gjirokastër and Sarandë regions[lower-alpha 25][lower-alpha 26][95][lower-alpha 27] and in four settlements within the coastal Himarë area[lower-alpha 25][lower-alpha 26][95][lower-alpha 27][100] where they form an overall majority population.[lower-alpha 25][lower-alpha 28] Greek speaking settlements are also found within Përmet municipality, near the border.[102][103] Some Greek speakers are also located within the wider Korçë region.[104] Due to both forced and voluntary internal migration of Greeks within Albania during the communist era,[lower-alpha 27][lower-alpha 29] some Greek speakers are also located within the wider Përmet and Tepelenë regions.[lower-alpha 27] Outside the area defined as Northern Epirus, two coastal Greek speaking villages exist near Vlorë.[105][106] While due to forced and non-forced internal population movements of Greeks within Albania during the communist era,[lower-alpha 27][lower-alpha 29] some Greek speakers are also dispersed within the wider Berat,[lower-alpha 30] Durrës, Kavajë, Peqin, Elbasan and Tiranë regions.[lower-alpha 27] In the post-1990 period, like many other minorities elsewhere in Balkans, the Greek population has diminished because of heavy migration. However, after the Greek economic crisis (2009), members of the Greek minority returned to Albania.[108][109]

Current issues

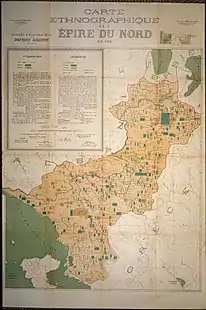

Ethnographic map of Northern Epirus in 1913, presented by Greece in Paris Peace Conference (1919)."The Orthodox Christian communities are recognized as juridical persons, like the others. They will enjoy the possessions of property and be free to dispose of it as they please. The ancient rights and hierarchical organization of the said communities shall not be impaired except under agreement between the Albanian Government and the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople.

Education shall be free. In the schools of the Orthodox communities the instruction shall be in Greek. In the three elementary classes Albanian will be taught concurrently with Greek. Nevertheless, religious education shall be exclusively in Greek.

Liberty of language:The permission to use both Albanian and Greek shall be assured, before all authorities, including the Courts, as well as the elective councils.

These provisions will not only be applied in that part of the province of Corytza now occupied militarily by Albania, but also in the other southern regions." —From the Protocol of Corfu, signed by Epirote and Albanian delegates, May 17, 1914[110]The protocol's terms were never fully implemented because of the politically unstable situation in Albania following the outbreak of World War I, and it was eventually annulled in 1921 during the Conference of Ambassadors.[111]

While violent incidents have declined in recent years, the ethnic Greek minority has pursued grievances with the government regarding electoral zones, Greek-language education, and property rights. On the other hand, minority representatives complain of the government's unwillingness to recognize the possible existence of ethnic Greek towns outside communist-era 'minority zones'; to utilize Greek on official documents and on public signs in ethnic Greek areas; to ascertain the size of the ethnic Greek population; and to include more ethnic Greeks in public administration.[112]

Protests against irregularities in 2011 census

The census of October 2011 included ethnicity for the first time in post-communist Albania, a long-standing demand of the Greek minority and of international organizations.[115] However, Greek representatives already found this procedure unacceptable due to article 20 of the Census law, which was proposed by the nationalist oriented Party for Justice, Integration and Unity and accepted by the Albanian government. According to this, there is a $1,000 fine for someone who will declare anything other than what was written down on his birth certificate,[116] including certificates from the communist-era where minority status was limited to only 99 villages.[117][118] Indeed, Omonoia unanimously decided to boycott the census, since it violates the fundamental right of self-determination.[119] Moreover, the Greek government called its Albanian counterpart for urgent action, since the right of free self-determination is not being guaranteed under these circumstances.[120] Vasil Bollano, the head of Omonoia declared that: "We, as minority representatives, state that we do not acknowledge this process, nor its product and we are calling our members to refrain from participating in a census that does not serve the solution of current problems, but their worsening".[121]

According to the census, there were 17,622 Greeks in the country's south (counties of Gjirokastër, Vlorë, and Berat) while 24,243 in Albania in general. Apart from these numbers, an additional 17.29% of the population of those counties refused to answer the optional question of ethnicity (compared to 13.96% of the total population in Albania).[122] On the other hand, Omonoia conducted its own census in order to count the members of the ethnic Greek minority. A total of 286,852 were counted, which equals to ca. 10% of the population of the country. During the time the census was conducted, half of these individuals resided permanently in Greece, but 70% visit their country of origin at least three times a year.[123]

Land distribution and property in post-communist Albania

The return to Albania of ethnic Greeks that were expelled during the past regime seemed possible after 1991. However, the return of their confiscated properties is even now impossible, due to Albanian's inability to compensate the present owners. Moreover, the full return of the Orthodox Church property also seems impossible for the same reasons.[66]

Education

Greek education in the region was thriving during the late Ottoman period (18th–19th centuries). When the First World War broke out in 1914, 360 Greek language schools were functioning in Northern Epirus (as well as in Elbasan, Berat, Tirana) with 23,000 students.[124] In this period, Romanian schools for the Aromanian population of the general region of Epirus were also present, though after the split of the region between Albania and Greece they were progressively closed.[125] Likewise, in Northern Epirus, during the following decades the majority of Greek schools were closed and Greek education was prohibited in most districts. In the post-communist period (after 1991), the reopening of schools was one of the major objectives of the minority. In April 2005 a bilingual Greek-Albanian school in Korçë,[126] and after many years of efforts, a private Greek school was opened in the Himara municipality in spring of 2006.[127]

Minority zone

In 1921–1991, there were minority zones where members of national minorities in Albania could exercise their cultural rights. In accordance with the final settlement in the League of Nations on minority populations in Albania, a specific minority zone was established for communities where the majority identified as Greeks in the territory of Albania in 1921. The League of Nations recognized as part of the minority zone 99 settlements in the Gjirokastër-Sarandë areas and 3 villages in Himara (Himarë, Palasë, Dhërmi). After 1945, the minority zone was re-established by the new Albanian government under the Communist Party of Albania and excluded the three villages along the Himara coast.[128] Greeks as an officially recognized national minority held co-equal cultural and political rights within these communities but as these rights were defined on a territorial basis, they were largely absent outside the minority zone. As such, education in Greek which was institutionally protected within the minority zone as well as other rights, didn't exist outside this zone and was subject to geographical restrictions.[129][130]

After 1991, rights which were exclusive to the minority zone were gradually made non-geographical and applicable throughout Albania. As such, the Law on Protection of National Minorities (2017) explicitly stipulates that linguistic and cultural rights of minorities can be exercised "in the entire territory of Albania". The right to education (funded by state institutions) and the right to use a non-Albanian language in local administration are partially defined territorially and require that at least 20% of the population of an area has to belong to a minority community and request the exercise of such rights.[131]

Greece

In 1991, the Greek Prime Minister Konstantinos Mitsotakis specified that the issue, according to the Greek minority in Albania, focuses on 6 major topics that the post-communist Albanian government should deal with:[66]

- The return of the confiscated property of the Orthodox Church and the freedom of religious practice.

- Functioning of Greek language schools (both public and private) in all the areas that Greek populations are concentrated.

- The Greek minority should be allowed to found cultural, religious, educational and social organizations.

- Illegal dismissals of members of the Greek minority from the country's public sector should be stopped and same rights for admission should be granted (on every level) for every citizen.

- The Greek families that left Albania during the communist regime (1945–1991), should be encouraged to return to Albania and acquire their lost properties.

- The Albanian government should take the initiative to conduct a census on ethnological basis and give its citizens the right to choose their ethnicity without limitations.

Albania

In 1993, the Albanian authorities admitted for the first time that Greek minority members exist not only in the designated 'minority zones' but all over Albania.[132]

Incidents

- In April 1994, Albania announced that unknown individuals attacked a military camp near the Greek-Albanian border (Peshkëpi incident), with two soldiers killed. Responsibility for the attack was taken by MAVI (Northern Epirus Liberation Front), which officially ceased to exist at the end of World War II. This incident triggered a serious crisis in Albanian-Greek relations.[132]

- The killing of Konstantinos Katsifas in Bularat, close to the Greek-Albanian border during the Greek national celebrations on the 28th October 2018. He was shot dead by the RENEA special forces of the Albanian police near the village after allegedly opening fire against the Albanian police. Early Greek media reports mention that this happened as they tried to lower the Greek flag he had raised at a cemetery in honour of fallen Greek soldiers.[133][134] Later reporting from sources in the Greek police dismissed these accounts as baseless.[135] The Albanian police reports that the events that led to his death began when he was approached by police vehicles after seen shooting in the air.[136]

See also

References

Explanatory notes

- "...northern Epirus (now southern Albania) with its substantial Greek minority"[1]

- "Northern Epirus is the southern part of Albania... The Christian Greeks revolted and formed a provisional and autonomous government."[3]

- "This area called 'Northern Epirus' by many Greeks, is regarded as geographically, historically, ethnologically and culturally connected with the northern Greek territory of Epirus since antiquity... The term 'Northern Epirus' (which Albania rejects as irredentist) started to be used by Greece around 1913."[4]

- "χρησιμοποιεί τον όρο «Βόρειος Ήπειρος» ώστε να περιγράψει βόρειες περιοχές του βιλαετίου Ιωαννίνων, κυρίως του σαντζακίου Αργυροκάστρου, στις οποίες εκτεινόταν η δικαιοδοσία του. Είναι από τις πρώτες χρήσεις του όρου σε διπλωματικά έγγραφα.."[8]

- "Appian's description of the Illyrian territories records a southern boundary with Chaonia and Thesprotia, where ancient Epirus began south of river Aous (Vjose)."[12]

- "This figure seems to fill the huge gap between the figures concerning the Greek minority in Albania given by Albanian sources at about 60,000 and the Greek official statistics of 'Greeks' in Albania of 300–400,000. In the national Greek view, Hellenic cultural heritage is seen as passed on through Byzantine culture to the Greek Orthodox religion today. Religion, as a criterion of classification, automatically places all the Albanian Aromanians, and also those people who call themselves Albanian Orthodox, into the 'Greek minority'."[25]

- "The fact that the Christian communities within the territory which was claimed by Greece from the mid 19th century until the year 1946, known after 1913 as Northern Epirus, spoke Albanian, Greek and Aromanian (Vlach), was dealt with by the adoption of two different policies by Greek state institutions. The first policy was to take measures to hide the language(s) the population spoke, as we have seen in the case of "Southern Epirus". The second was to put forth the argument that the language used by the population had no relation to their national affiliation. To this effect the state provided striking examples of Albanian speaking individuals (from southern Greece or the Souliotēs) who were leading figures in the Greek state. As we will discuss below, under the prevalent ideology in Greece at the time every Orthodox Christian was considered Greek, and conversely after 1913, when the territory which from then onwards was called "Northern Epirus" in Greece was ceded to Albania, every Muslim of that area was considered Albanian."[26]

- "In February 1913, Greek troops captured Ioannina, the capital of Epirus. The Turks recognised the gains of the Balkan allies by the Treaty of London of May 1913."[27]

- "The Second Balkan War was of short duration and the Bulgarians were soon forced to the negotiating table. By the Treaty of Bucharest (August 1913) Bulgaria was obliged to accept a highly unfavorable territorial settlement, although she did retain an Aegean outlet at Dedeagatch (now Alexandroupolis in Greece). Greece's sovereignty over Crete was now recognized but her ambition to annex Northern Epirus, with its substantial Greek population, was thwarted by the incorporation of the region into an independent Albania."[28]

- "...in Northern Epirus loyalty to an Albania with a variety of Muslim leaders competing in anarchy cannot have been strong. In Macedonia, where Greece managed to hold on to large territorial gains,she faced a Bulgarian minority with its own Church and quite a long-establish nationali identity. The same cannot be said of the Albanians in Northern Epirus."[29]

- "When the Greek army withdrew from Northern Epirot territories in accordance with the ruling of the Powers, a fierce struggle broke out between Muslim Albanians and Greek irregulars."[32]

- "In May 1914, the Great Powers signed the Protocol of Corfu, which recognized the area as Greek, after which it was occupied by the Greek army from October 1914 until October 1915."[33]

- "Under King Zog, the Greek villages suffered considerable repression, including the forcible closure of Greek-language schools in 1933–34 and the ordering of Greek Orthodox monasteries to accept mentally sick individuals as inmates."[33]

- "Sederholm did add, however, that the Albanian government opposed the teaching of Greek in Albanian schools 'because it fears the influence of the teachers, the majority of whom have openly declared themselves in favour of the Pan—Epirot movement.'"[37]

- "Southern Albania, and particularly the Prefecture of Gjirokastër, was a sensitive region from this point of view, since the most wide—spread educational network there at the end of the Ottoman rule was that of the 'Greek schools', serving the Orthodox Christian population. Since the Albanian government recognised the rights of minorities as a member of the League of Nations in October 1921, these Greek schools were legalized, but only in Greek-speaking villages, and could continue to function or reopen (those that had been closed during the Italian occupation of 1916-1920). From the point of view of the state, the existence of Greek schools (of varied status and with private or publicly financed teachers)' represented a problem for the integration of the 'Greek-speaking minority' and more generally for the integration of the Orthodox Christians. They were the only non-Albanian schools remaining in the region after Albanian state schools (henceforth for Muslims and Christians alike) had replaced the 'Ottoman schools' in Muslim villages and the 'Greek schools' in Christian villages, while Aromanian (Kostelanik 1996) and Italian schools had been closed."[38]

- "Πιο συγκεκριμένα, στο προστατευτικό νομικό πλαίσιο της μειονότητας συμπεριλήφθηκαν μόνο οι Έλληνες που κατοικούσαν στις περιφέρειες Αργυροκάστρου και Αγίων Σαράντα και σε τρία από τα χωριά της Χιμάρας (Χιμάρα, ∆ρυμάδες και Παλάσσα), ενώ αποκλείστηκαν αυθαίρετα όσοι κατοικούσαν στην περιοχή της Κορυτσάς και στα υπόλοιπα τέσσερα χωριά της Χιμάρας Βούνο, Πήλιουρι, Κηπαρό και Κούδεσι, αλλά και όσοι κατοικούσαν στα μεγάλα αστικά κέντρα της 'μειονοτικής ζώνης', δηλαδή στο Αργυρόκαστρο, τους Άγιους Σαράντα και την Πρεμετή, πόλεις με μικτό βέβαια πληθυσμό αλλά εμφανή τον ελληνικό τους χαρακτήρα την εποχή εκείνη. Αυτό πρακτικά σήμαινε ότι για ένα μεγάλο τμήμα του ελληνικού στοιχείου της Αλβανίας δεν αναγνωρίζονταν ούτε τα στοιχειώδη εκείνα δικαιώματα που προέβλεπαν οι διεθνείς συνθήκες, ούτε βέβαια το δικαίωμα της εκπαίδευσης στη μητρική γλώσσα, που κυρίως μας ενδιαφέρει εδώ."[39]

- "Ιδιαίτερο ενδιαφέρον από ελληνικής πλευράς παρουσίαζαν οι πόλεις του Αργυροκάστρου, των Αγιών Σαράντα καιτης Κορυτσάς, γνωστά κέντρα του ελληνισμού της Αλβανίας, και στη συνέχεια η Πρεμετή και η Χιμάρα. ΘΘα πρέπει ίσως στο σημείο αυτό να θυμίσουμε ότι για του ςΈλληνες των αστικών κέντρων, με εξαίρεση τη χιμάρα, δεν αναγνωρίζοταν το καθεστώς του μειονοτικού ούτε τα δικαιώματα που απέρρεαν από αυτό."[40]

- "Ήδη από τις αρχές του σχολικού έτους 1925-26 ξεκίνησαν οι προσπάθειες για το άνοιγμα ενός σχολείου στους Άγιους Σαράντα, τους οποίους μάλιστα οι ελληνικές αρχές, σε αντίθεση με τις αλβανικές, δεν συγκατέλεγαν μεταξύ των 'αλβανόφωνων κοινοτήτων', καθώς ο ελληνικός χαρακτήρας της πόλης ήταν πασιφανής. Σε ό,τι αφορούσε το ελληνικό σχολείο της πόλης, η Επιτροπή επί των Εκπαιδευτικών σχεδίαζε να το οργανώσει σε διδασκαλείο, τοποθετώντας σε αυτό υψηλού επιπέδου και ικανό διδασκαλικό προσωπικό, ώστε να αποτελέσει σημαντικό πόλο έλξης για τα παιδιά της περιοχής, αλλά και παράδειγμα οργάνωσης και λειτουργίας σχολείου και για τις μικρότερες κοινότητες. Τις μεγαλύτερες ελπίδες για την επιτυχία των προσπαθειών της φαίνεται ότι στήριζε η Επιτροπή στην επιμονή του ελληνικού στοιχείου της πόλης, στην πλειοψηφία τους ευκατάστατοι έμποροι που θα ήταν διατεθειμένοι να προσφέρουν ακόμη και το κτίριο για τη λειτουργία του, αλλά και στην παρουσία και τη δραστηριοποίηση εκεί του ελληνικού υποπροξενείου 58 . Όλες οι προσπάθειες ωστόσο αποδείχθηκαν μάταιες και ελληνικό κοινοτικό σχολείο δεν λειτούργησε στην πόλη όχι μόνο το σχολικό έτος 1925-26, αλλά ούτε και τα επόμενα χρόνια."[41]

- "Until the 1960s, Lunxhëri was mainly inhabited by Albanian-speaking Orthodox Christians called the Lunxhots. By then, and starting during and just after the Second World War, many of them had left their villages to settle in Gjirokastër and in the towns of central Albania, where living conditions and employment opportunities were considered better. They were replaced, from the end of the 1950s on, by Vlachs, forced by the regime to settle in agricultural cooperatives. Some Muslim families from Kurvelesh, in the mountainous area of Labëria, also came to Lunxhëri at the same time – in fact, many of them were employed as shepherds in the villages of Lunxhëri even before the Second World War. While Lunxhëri practiced (as did many other regions) a high level of (territorial) endogamy, marriage alliances started to occur between Christians Lunxhots and members of the Greek minority of the districts of Gjirokastër (Dropull, Pogon) and Sarandë. Such alliances were both encouraged by the regime and used by people to facilitate internal mobility and obtain a better status and life-chances."[42] "The issue of a couple of new villages created during communism illustrates this case. The village of Asim Zenel, named after a partisan from Kurvelesh who was killed in July 1943, was created as the centre of an agricultural cooperative in 1947 on the road leading from Lunxhëri to Dropull. The people who were settled in the new village were mainly shepherds from Kurvelesh, and were Muslims. The same thing happened for the village of Arshi Llongo, while other Muslims from Kurvelesh settled in the villages of lower Lunxhëri (Karjan, Shën Todër, Valare) and in Suhë. As a result, it is not exceptional to hear today from the Lunxhots, such as one of my informants, a retired engineer living in Tirana, that 'in 1945 a Muslim buffer-zone was created between Dropull and Lunxhëri to stop the Hellenisation of Lunxhëri. Muslims were thought to be more determined against Greeks. At that time, the danger of Hellenisation was real in Lunxhëri'. In the village of Këllëz people also regret that 'Lunxhëri has been surrounded by a Muslim buffer-zone by Enver Hoxha, who was himself a Muslim'."[43] "By the end of the nineteenth century, however, during the period of the kurbet, the Lunxhots were moving between two extreme positions regarding ethnic and national affiliation. On the one hand, there were those who joined the Albanian national movement, especially in Istanbul, and made attempts to spread a feeling of Albanian belonging in Lunxhëri. The well-known Koto Hoxhi (1825-1895) and Pandeli Sotiri (1843-1891), who participated in the opening of the first Albanian school in Korçë in 1887, were both from Lunxhëri (from the villages of Qestorat and Selckë). On the other hand were those who insisted on the Greekness of the Lunxhots and were opposed to the development of an Albanian national identity among the Christians."[44]

- "During the mid-war period and the period between WWII and the foundation of the communist regime in Albania, there is a wave of relocations of Greek and Albanian Christians from South Albania to Greek Epirus, who have become known as "Vorioepirotes", meaning Greeks who come from the part of Epirus that was yielded to Albania and is since called by Greeks "Northern Epirus". The "Vorioepirotes" of Albanian origin have to a large extent formed Greek consciousness and identity and this is why they choose to come to Greece, where they are dealt with just like the rest. On the contrary, only Muslims who have developed Albanian national consciousness or who cannot identify with either Greeks or Turks leave Greece for Albania, which they choose due to ethnic, language and religious affinity. Let's note that the flight of the Vorioepirotes" of both Greek and Albanian origin persists in the form of escape during the communist regime, despite the Draconian security measures on the border, though to a much lesser degree."[52]

- "In 1991, Greek shops were attacked in the coastal town of Saranda, home to a large minority population, and inter-ethnic relations throughout Albania worsened".[65]

- "This war of words culminated in the arrest by the Albanian authorities in May of six members of the Onomoia, the main Greek minority organization in Albania. At their subsequent trial, five of the six received prison sentences of between six and eight years for treasonable advocacy of the secession of "Northern Epirus" to Greece and the illegal possession of weapons."[68]

- "...the area studied was confined to the southern border fringes, and there is good reason to believe that this estimate was very low"."Under this definition, minority status was limited to those who lived in 99 villages in the southern border areas, thereby excluding important concentrations of Greek settlement in Vlorë (perhaps 8000 people in 1994) and in adjoining areas along the coast, ancestral Greek towns such as Himara, and ethnic Greeks living elsewhere throughout the country. Mixed villages outside this designated zone, even those with a clear majority of ethnic Greeks, were not considered minority areas and therefore were denied any Greek-language cultural or educational provisions. In addition, many Greeks were forcibly removed from the minority zones to other parts of the country as a product of communist population policy, an important and constant element of which was to pre-empt ethnic sources of political dissent. Greek place-names were changed to Albanian names, while use of the Greek language, prohibited everywhere outside the minority zones, was prohibited for many official purposes within them as well."[74]

- "Greek co ethnics who are Albanian citizens (Voreioepirotes) hold Special Identity Cards for Omogeneis (co-ethnics) (EDTO) issued by the Greek police. EDTO holders are not included in the Ministry of Interior data on aliens. After repeated requests, the Ministry of Interior has released data on the actual number of valid EDTO to this date. Their total number is 189,000." Data taken from Greek ministry of Interiors.[94]

- "According to the latest census in the area, the Greek-speaking population is larger but not necessarily continuous and concentrated. The exclusively Greek-speaking villages, apart from Himarë, are Queparo Siperme, Dhërmi and Palasë. The rest are inhabited by Albanian-speaking Orthodox Christians (Kallivretakis 1995:25-58).";[97] "The Greek minority of Albania is found in the southern part of the country and it mostly constitutes a compact group of people. Apart from the cities (Gjirokastër, Sarandë), whose population is mixed, the villages of these two areas, which are officially recognized as minority areas, are in the vast majority of their population Greek and their historical presence in this geographical space, has led to an identification of the group with this place."[98]

- "But in spite of the efforts of Greek schools and churches near Vlorë, Berat and Korçë, Greek speech only really exists today in the extreme south-west of Albania near Butrint and along the border as far as Kakavia, in three villages along the coast near Himarë, and in the Drinos valley near Gjirokastër. Even in these areas there are pockets of Albania speech, and almost all Greek-speakers are bilingual. Emigration to Greece has in the past ten years both emptied certain villages and increased the number of Greek-speakers. Pro-Greek feelings may have existed at other opportune times among people who spoke Albanian at home, but were Orthodox in religion and spoke Greek in commercial dealing or at church."[99]

- "Another factor contributing to the lower rate of increase in the Greek minority is the internal movement of the ethnic Greeks. The women who marry non-Greeks outside the minority areas often give up their Greek nationality. The same thing can be said about the ethnic Greeks, especially those with university training, who would be employed outside their villages. In particular, those working in large cities like Tirana very often would not declare their Greek nationality."; "As can be seen from Table I, the preponderant number of Greek nationals, 57,602, live in southern Albania, south of the Shkumbin River. Only 1,156 ethnic Greeks reside outside of this region, principally in the cities of Tirana, Durres and Elbasan. Thus, in southern Albania, with an area of 13,000 square kilometers and a population of 1,377,810, the Greek minority makes up 4.18 percent of the overall population. But the highest concentration of the Greek minority is located in an area of I ,000 square kilometers in the enclaves of Pogon, Dropull and Vurg, specifically, the townships of Lower Dropull, Upper Dropull and Pogon, in the district of Gjirokastra; the townships of Vergo, Finiq, Aliko, Mesopotam and the city of Delvina in the district of Delvina; and the townships of Livadhja, Dhiver and the city of Saranda, in the district of Saranda. This concentration has a total population of 53,986 ethnic Greeks. In turn, these enclaves are within the districts of Gjirokastra, Delvina and Saranda, with an area of 2,234 square kilometers which contains a total of 56,452 ethnic Greeks, or 36.6 percent of the general population of 154,141 in the region."[96]

- "The coastal Himara region of Southern Albania has always had a predominantly ethnic Greek population."[101]

- "In contrast, Albanian governments use a much lower figure of 58,000 which rests on the unrevised definition of "minority" adopted during the communist period. Under this definition, minority status was limited to those who lived in 99 villages in the southern border areas, thereby excluding important concentrations of Greek settlement in Vlora (perhaps 8000 people in 1994) and in adjoining areas along the coast, ancestral Greek towns such as Himara, and ethnic Greeks living elsewhere throughout the country. Mixed villages outside this designated zone, even those with a clear majority of ethnic Greeks, were not considered minority areas and therefore were denied any Greek-language cultural or educational provisions. In addition, many Greeks were forcibly removed from the minority zones to other parts of the country as a product of communist population policy, an important and constant element of which was to pre-empt ethnic sources of political dissent. Greek place-names were changed to Albanian names, while use of the Greek language, prohibited everywhere outside the minority zones, was prohibited for many official purposes within them as well."[74]

- "Berat was the seat of a Greek bishopric... and today Vlach- and even Greek-speakers can be found in the town and the villages near by".[107]

- "Ethnic Greek minority groups had encouraged their members to boycott the census, affecting measurements of the Greek ethnic minority and membership in the Greek Orthodox Church."[113]

- "Portions of the census dealing with religion and ethnicity have grabbed much of the attention, but entire parts of the census might not have been conducted according to the best international practices, Albanian media reports..."[114]

Citations

- Smith, Michael Llewellyn (1999). Ionian vision: Greece in Asia Minor, 1919-1922 (New edition, 2nd impression ed.). London: C. Hurst. p. 36. ISBN 9781850653684.

- Douglas, Dakin (1962). "On+28+February+1914" "The Diplomacy of the Great Powers and the Balkan States, 1908–1914". Balkan Studies. 3: 372–374. Retrieved 2010-11-09.

- Pentzopoulos, Dimitri (2002). The Balkan Exchange of Minorities and its Impact on Greece. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. p. 28. ISBN 9781850657026.

- Konidaris 2005, p. 66

- Tucker, Spencer; Roberts, Priscilla Mary (2005). World War I: encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 77. ISBN 978-1-85109-420-2. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

- Miller, William (1966). The Ottoman Empire and Its Successors, 1801-1927. Routledge. pp. 543–544. ISBN 978-0-7146-1974-3.

- Douzougli, Angelika; Papadopoulos, John (2010). "Liatovouni: a Molossian cemetery and settlement in Epirus". Jahrbuch des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts. 125: 3.

- Skoulidas, Ilias (2001). The Relations Between the Greeks and the Albanians during the 19th Century: Political Aspirations and Visions (1875-1897). Didaktorika.gr (Thesis). University of Ioannina. p. 230. doi:10.12681/eadd/12856. hdl:10442/hedi/12856.

- Hatzopoulos, M. B.; Sakellariou, M.; Loukopoulou, L. D. (1997). Epirus, Four Thousand Years of Greek History and Civilization. Ekdotike Athenon. ISBN 960-213-377-5.

The above review suggest that the northern boundaries of Hellenism in Epirus during Classical Antiquity lay in the valley of the Aoos.

- Boardman & Hammond 1970.

- Smith, William (2006). A New Classical Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography, Mythology and Geography. Whitefish, MT, USA: Kessinger Publishing. p. 423.

- Wilkes 1996, p. 92.

- Filos, Panagiotis (December 18, 2017). Giannakis, Georgios; Crespo, Emilio; Filos, Panagiotis (eds.). The Dialectal Variety of Epirus. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 9783110532135.

The boundaries of Epirus, especially to the north cannot be determined with accuracy nowadays due to their instability throughout ancient times, but also because of the coexistence of the Greek population(s) with non-Greek peoples, notably the Illyrians: note, for instance, that Apollonia, originally a Corinthian colonyh, is considered part of Epirus by some later ancient historians (Strabo 2.5.40, 16.2.43), whereas some others, of equally or even later times, place it within Illyria (Stephanus Byzantius 105.20, 214.9). Nonetheless, one may say with some degree of certainty that from the 4th c. BC onwards the geographic boundaries of Epirus were by and large set as follows: the so called Keraunia or Akrokeraunia mountain range to the north (modern day S. Albania), the Ambracian Gulf to the south, the Pindus (Pindos) mountain range to the east, and the Ionian Sea to the west...

- Skoulidas, Ilias (2001). The relations between the Greeks and the Albanians during the 19th century: political aspirations and visions (1875 - 1897) (Thesis). University of Ioannina. p. 61. doi:10.12681/eadd/12856. hdl:10442/hedi/12856. Retrieved 2 May 2020.

νομείς της οθωμανικής εξουσίας στην Ήπειρο και στην Αλβανία ήταν κυρίως μουσουλμάνοι Αλβανοί.

- Winnifrith 2002, p. 108.

- Gregorič 2008, p. 126.

- Skendi, Stavro (1967). The Albanian National Awakening, 1878-1912. Princeton University Press. ISBN 1400847761.

- Greek, Roman and Byzantine studies. Duke University. 1981. p. 90.

- Katherine Elizabeth Fleming. The Muslim Bonaparte: diplomacy and orientalism in Ali Pasha's Greece. Princeton University Press, 1999. ISBN 978-0-691-00194-4

- Sakellariou, M. V. (1997). Epirus, 4000 years of Greek history and civilization. Ekdotike Athenon. p. 255. ISBN 978-960-213-371-2.

- Pappas, Nicholas Charles (1991). Greeks in Russian military service in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Nicholas Charles Pappas. pp. 318, 324. ISBN 0-521-23447-6.

- Surrealism in Greece: An Anthology. Nikos Stabakis. University of Texas Press, 2008. ISBN 0-292-71800-4

- The military in Greek politics: from independence to democracy. Thanos Veremēs. Black Rose Books, 1998 ISBN 1-55164-105-4

- Nußberger & Stoppel 2001, p. 8.

- Schwandner-Sievers, Stephanie (1999). "The Albanian Aromanians' Awakening: Identity Politics and Conflicts in Post-Communist Albania" (PDF). ECMI Working Paper #3. European Centre for Minority Issues.

- Baltsiotis, Lambros (2011). "The Muslim Chams of Northwestern Greece". European Journal of Turkish Studies (12). doi:10.4000/ejts.4444.

- Clogg 2002, p. 79.

- Clogg 2002, p. 81.

- Winnifrith 2002, p. 130.

- Pettifer 2001, p. 4.

- Stickney 1926

- Smith, Michael Llewellyn (2006). "Venizelos' diplomacy, 1910-23: From Balkan alliance to Greek-Turkish Settlement". In Kitromilides, Paschalis (ed.). Eleftherios Venizelos: the trials of statesmanship. Edinburgh University Press. p. 150. ISBN 9780748624782.

- Pettifer 2001, p. 5.

- Stavrianos, Leften Stavros; Stoianovich, Traian (2008). The Balkans since 1453. Hurst & Company. p. 710. ISBN 978-1-85065-551-0. Retrieved 10 February 2011.

- Griffith W. Albania and the Sino-Soviet Rift. Cambridge, Massachusetts: 1963: 40, 95.

- Roudometof & Robertson 2001, p. 189.

- Austin, Robert Clegg (2012). Founding a Balkan State: Albania's Experiment with Democracy, 1920-1925. University of Toronto Press. p. 93. ISBN 9781442644359.

- Clayer, Nathalie (2012). "Education and the integration of the Province of Gjirokastër in interwar Albania". In Kera, Gentiana; Enriketa Pandelejmoni (eds.). Albania: family, society and culture in the 20th century. LIT Verlag. p. 98.

- Manta 2005, p. 30.

- Manta 2005, p. 52.

- Manta 2005, p. 54.

- De Rapper 2005, p. 175.

- De Rapper 2005, p. 181.

- De Rapper 2005, p. 182.

- George H. Chase. Greece of Tomorrow, ISBN 1-4067-0758-9, page 41.

- Richard Clogg (20 June 2002). A Concise History of Greece. Cambridge University Press. pp. 118–119. ISBN 978-0-521-00479-4. OCLC 1000695918.

- Ruches 1965.

- James Pettifer; Hugh Poulton (1994). The Southern Balkans. Minority Rights Group. p. 33.

- Vickers & Pettifer 1997.

- Skoulidas, Ilias (2012). Greek-Albanian Relations (PDF). Macedonian Studies. p. 217. ISBN 978-960-467-342-1.

- Milica Zarkovic Bookman (1997). The demographic struggle for power: the political economy of demographic engineering in the modern world. Routledge. p. 245. ISBN 978-0-7146-4732-6.

- Nitsiakos 2010, pp. 57–58.

- Second Report Submitted By Albania Pursuant to Article 25, Paragraph 1 Archived 2009-03-19 at the Wayback Machine, of the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities.

- Dalakoglou 2010, p. 136; Green 2012, pp. 111–112, 115.

- Vickers & Pettifer 1997, p. 187.

- Vickers & Pettifer 1997, p. 189.

- Clogg, Richard (2017). Greek to Me: A Memoir of Academic Life. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 113. ISBN 9781786732620.

- "www.drustvo-antropologov.si" (PDF).

- Kondis, Basil (1995). "The Greek minority in Albania". Balkan Studies. 36 (1): 91. Retrieved 6 September 2016.

- Allcock 1992, p. 7.

- Vickers & Pettifer 1997, p. 190.

- Konidaris, Gerasimos (2013). "Examining policy responses to immigration in the light of interstate relations and foreign policy objectives". In King, Russell (ed.). New Albanian Migration. Liverpool University Press.

- Dimitropoulos, Kontsantinos-Fotios (2011). The Social and Political Structure of Hellenism in Albania in the Post-Hotza Era. www.didaktorika.gr (Doctoral Dissertation). Panteion University. pp. 218–220. doi:10.12681/eadd/23044. hdl:10442/hedi/23044. Retrieved 10 July 2023.

Στις "μειονοτικές ζώνες" δημιουργούνται νέα χωριά με εποίκους ή μικτοποιούνται άλλα που παραδοσιακά κατοικούνται αποκλειστικά από Έλληνες...Στην Χιμάρα... η μετάβαση στον πολικοματισμόο βρίσκει να διαμένουν μόνιμα στην κωμόπολη, τριακόσιες οικογένειες Αλβανών ... δημιουργήθηκε ένας νέος οικισμός 3.000 αλβανοτσάμηδων, η Γκιάστα.

- Hupchick, D. (11 January 2002). The Balkans: From Constantinople to Communism. Springer. p. 361. ISBN 978-0-312-29913-2.

- Pettifer 2001, p. 10.

- Valeria Heuberger; Arnold Suppan; Elisabeth Vyslonzil (1996). Brennpunkt Osteuropa: Minderheiten im Kreuzfeuer des Nationalismus (in German). Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag. p. 74. ISBN 978-3-486-56182-1.

- Vickers & Pettifer 1997, p. 198.

- Clogg 2002, p. 214.

- Greek Helsinki Monitor: Greeks of Albania and Albanians in Greece Archived 2009-03-16 at the Wayback Machine, September 1994.

- World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous People Archived 2014-11-15 at the Wayback Machine: Albanian overview: Greeks.

- "Albanian nationalists increase tensions with gunshots". Eleutherotypia (in Greek). 20 August 2010. Archived from the original on 9 December 2017.

- Vickers, Miranda (2010). The Greek Minority in Albania – Current Tensions (PDF). Research & Assessment Branch. pp. 6–7. ISBN 978-1-905962-79-2.

- Feta, Bledar (2018). "Bilateral Governmental Communication: A Tool for Stronger Albanian-Greek Relations". Albania and Greece: Understanding and explaining. Friedrich Ebert Foundation. pp. 73, 77–79, 81–82. ISBN 978-9928-195-22-7.

- Pettifer 2001, p. 6.

- "Final census findings lead to concerns over accuracy". Tirana Times. Archived from the original on 28 May 2014. Retrieved 26 May 2014.

- Likmeta, Besar (6 July 2011). "Albania Moves Ahead With Disputed Census". Balkaninsight. Retrieved 26 May 2014.

- "Three Albanian journalists awarded with "World at 7 Billion Prize"". United Nations (Albania). Archived from the original on 28 May 2014. Retrieved 26 May 2014.

...the controversial CENSUS data

- survival, cultural (19 March 2010). ""Northern Epiros": The Greek Minority in Southern Albania".

- "Bilateral relations between Greece and Albania". Ministry of Foreign Affairs-Greece in the World. Archived from the original on July 17, 2006. Retrieved September 6, 2006.

- "Plan for Albania" (PDF). p. 3.

- Nicholas V. Gianaris. Geopolitical and economic changes in the Balkan countries Greenwood Publishing Group, 1996 ISBN 978-0-275-95541-0, p. 4

- Jeffries, Ian (2002). Eastern Europe at the turn of the twenty-first century : a guide to the economies in transition. London: Routledge. p. 69. ISBN 0-203-24465-6. OCLC 52071941.

- "OMONIA's Census: Greek minority constitutes 10% of population in Albania". Independent Balkan News Agency. 11 December 2013. Archived from the original on 18 May 2021. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- Kasimi, Charalambos (8 March 2012). "Greece: Illegal Immigration in the Midst of Crisis". Migration Policy Institute.

- "Country Studies US: Greeks and Other Minorities". Retrieved September 6, 2006.

- Jeffries, Ian (1993-06-25). Eastern Europe at the end of the 20th century. Taylor & Francis. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-415-23671-3. Retrieved 2010-08-27.

- "UNPO". Archived from the original on October 5, 2006. Retrieved September 6, 2006.

- Jelokova Z.; Mincheva L.; Fox J.; Fekrat B. (2002). "Minorities at Risk (MAR) Project : Ethnic-Greeks in Albania". Center for International Development and Conflict Management, University of Maryland, College Park. Archived from the original on July 20, 2006. Retrieved July 26, 2006.

- CIA World Factbook (2006). "Albania". Retrieved July 26, 2006.

- The CIA World Factbook (1993) Archived 2017-01-26 at the Wayback Machine provided a figure of 8% for the Greek minority in Albania.

- "Albania". CIA. Retrieved 13 September 2014.

- Kosta Barjarba. "Migration and Ethnicity in Albania: Synergies and Interdependencies" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-11-14. Retrieved 2008-09-16.

- "Albania". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 13 September 2014.

- Triandafyllidou, Anna (2009). "Migration and Migration Policy in Greece. Critical Review and Policy Recommendations" (PDF). Hellenic Foundation for European and Foreign Policy (ELIAMEP). p. 3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-09-23. Retrieved 2016-01-30.

- Kallivretakis, Leonidas (1995). "Η ελληνική κοινότητα της Αλβανίας υπό το πρίσμα της ιστορικής γεωγραφίας και δημογραφίας [The Greek Community of Albania in terms of historical geography and demography." In Nikolakopoulos, Ilias, Kouloubis Theodoros A. & Thanos M. Veremis (eds). Ο Ελληνισμός της Αλβανίας [The Greeks of Albania]. University of Athens. pp. 51-58.

- Arqile, Berxholli; Protopapa, Sejfi; Prifti, Kristaq (1994). "The Greek minority in the Albanian Republic: A demographic study". Nationalities Papers. 22 (2): 430–431.

- Nitsiakos 2010, p. 99.

- Nitsiakos 2010, pp. 129–130.

- Winnifrith 2002, pp. 24–25.

- Winnifrith, Tom (1995). "Southern Albania, Northern Epirus: Survey of a Disputed Ethnological Boundary Archived 2015-07-10 at the Wayback Machine". Society Farsharotu. Retrieved 14-6-2015.

- "Albania: The state of a nation". ICG Balkans Report N°111. p. 15. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-08-08. Retrieved 2010-09-02.

- Dimitropoulos, Konstantinos (2011). Social and political policies regarding Hellenism in Albania during the Hoxha period (Thesis). Panteion University of Social and Political Sciences. p. 11.

- Nitsiakos 2010, pp. 249–263.

- Winnifrith 2002, p. 133.

- Nicholas Geoffrey Lemprière Hammond (1967). Epirus: the Geography, the Ancient Remains, the History and Topography of Epirus and Adjacent Areas. Clarendon Press. pp. 131-132.

- Dimitropoulos. Social and political policies regarding Hellenism. 2011. p. 13.

- Winnifrith 2002, p. 29.

- Ράπτη, Αθηνά (2014). "Εκπαιδευτική πολιτική σε ζητήματα ελληνόγλωσσης εκπαίδευσης στην Αλβανία: διερεύνηση αναγκών των εκπαιδευτικών και των μαθητών για τη διδασκαλία/εκμάθηση της ελληνικής γλώσσας". University of Macedonia: Department of Balkan, Slavic and Middle East Studies (in Greek): 49–50. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- Murrugarra, Edmundo; Larrison, Jennica; Sasin, Marcin, eds. (2010). Migration and poverty : toward better opportunities for the poor. Washington, D.C.: World Bank. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-8213-8436-7.

- Ruches 1965, pp. 92–93.

- Hall, Derek R.; Danta, Darrick R. (1996). Reconstructing the Balkans: a geography of the new Southeast Europe. Wiley. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-471-95758-4. Retrieved 13 February 2012.

- Minority Rights Group International, World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples - Albania: Greeks, 2008. UNHCR Refworld

- "International Religious Freedom Report for 2014: Albania" (PDF). www.state.gov. United States, Department of State. p. 5. Retrieved 20 October 2015.

- "Final census findings lead to concerns over accuracy". Tirana Times. 19 December 2012. Archived from the original on 2012-12-26.

- George Gilson (27 September 2010). "Bad blood in Himara". Athens News. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 4 November 2010.

- "Macedonians and Greeks Join Forces against Albanian Census". balkanchronicle. Archived from the original on 12 January 2012. Retrieved 24 September 2011.

- "Με αποχή απαντά η μειονότητα στην επιχείρηση αφανισμού της". ethnos.gr. Retrieved 27 September 2011.

- "Ανησυχίες της ελληνικής μειονότητας της Αλβανίας για την απογραφή πληθυσμού". enet.gr. Retrieved 27 September 2011.

- "Η ελληνική ομογένεια στην Αλβανία καλεί σε μποϊκοτάζ της απογραφής". kathimerini.gr. Retrieved 30 September 2011.

- "Albanian census worries Greek minority". athensnews. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ""Omonoia" and other minority organizations in Albania, are calling for a census boycott". en.sae.gr. Athens News Agency (ANA). Retrieved 11 December 2014.

- Census data: Resident population by ethnic and cultural affiliation Archived 2015-09-24 at the Wayback Machine

- "Omonias Census: Greek Minority Constitutes 10% of Population in Albania". Independent Balkan News Agency. 11 December 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2014.

- Nußberger & Stoppel 2001, p. 14.

- Solcanu, Ion I. (2015). "Școli române la sud de Dunăre, în Macedonia, Epir și Thesalia (1864-1900)". Analele Științifice ale Universității "Alexandru Ioan Cuza" din Iași. Istorie (in Romanian) (61): 297–311.

- "Albanische Hefte. Parlamentswahlen 2005 in Albanien" (PDF) (in German). Deutsch-Albanischen Freundschaftsgesellschaft e.V. 2005. p. 32. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-18.

- Gregorič 2008, p. 68.

- Vickers 2002, p. 3.

- Committee on the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities: Second Opinion on Albania 29 May 2008. Council of Europe: Secretariat of the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities.

- Albanian Human Rights Practices, 1993. Author: U.S. Department of State. January 31, 1994.

- Djordjević & Zaimi 2019, pp. 57–58.

- Konidaris 2005, p. 73: "The new Greek Minister of Foreign Affairs Mr. Papoulias ([...]), visited Tirana in mid-October [1993]. [...] For its part, the Albanian government admitted for the first time that the Greek minority existed not only in the designated minority areas, but all over the country. [...] On 10 April 1994, Albania announced that unknown individuals had attacked a military camp at Peshkepi (close to the border with Greece) and killed two soldiers. The responsibility for the attack was claimed by an organisation called MAVI (Front for the Liberation of Northern Epirus), which officially had ceased to exist since the end of World War II. This episode triggered the second and most serious crisis in relations between the two states in the 1990s ([...])."

- "Ethnic Greek man killed by Albanian police in shootout". Kathimerini. 28 October 2018.

- "Protesters gather outside Albanian Embassy in Athens over ethnic Greek's killing". Kathimerini. 2018. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- "Athens-Tirana ties put to test after killing of ethnic Greek man". Kathimerini. 2018. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

Earlier, Katsifas and other members of the Greek community in Bularat raised a Greek flag – on the occasion of the October 28 national holiday marking Greece's entry into World War II – at a cemetery for Greek soldiers. However, sources at the Greek Police (ELAS) said there was no evidence, nor witness accounts, linking Katsifas's death to that.

- "Man killed in shootout with police". Fox News. 2018.

Bibliography

History

- Allcock, John B. (1992). "Albania-Greece (Northern Epirus)". Border and Territorial Disputes. Longman. pp. 3–8. ISBN 978-0-582-20931-2.

- Boardman, John; Hammond, N.G.L. (1970). The Cambridge Ancient History - The Expansion of the Greek World, Eighth to Sixth Centuries B.C. Part 3: Volume 3. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-23447-6.

- Bowden, William (2003). Epirus Vetus: The Archaeology of a Late Antique Province. Duckworth. ISBN 978-0-7156-3116-4.

- Boardman, John; Sollberger, E. (1982). J. Boardman; I. E. S. Edwards; N. G. L. Hammond; E. Sollberger (eds.). The Cambridge Ancient History: The Prehistory of the Balkans; and the Middle East and the Aegean world, tenth to eighth centuries B.C. Vol. III (part 1) (2 ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521224969.

- Dalakoglou, Dimitris (2010). "The road: An ethnography of the Albanian-Greek cross-border motorway". American Ethnologist. 37 (1): 132–149. doi:10.1111/j.1548-1425.2010.01246.x. hdl:1871.1/46adcb87-0107-4e00-87e1-9130ee16b0fa. ISSN 0094-0496. JSTOR 40389883.

- Green, Sarah (2012). "Reciting the future: Border relocations and everyday speculations in two Greek border regions". HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory. 2 (1): 111–129. doi:10.14318/hau2.1.007. ISSN 2575-1433. S2CID 220744145.

- Stickney, Edith Pierpont (1926). Southern Albania or Northern Epirus in European International Affairs, 1912–1923. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-6171-0.

- Ruches, Pyrrhus J. (1965). Albania's captives. Chicago: Argonaut.

- Clogg, Richard (2002). Concise History of Greece (Second ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-80872-3.

- Roudometof, Victor; Robertson, Roland (2001). Nationalism, globalization, and orthodoxy: the social origins of ethnic conflict in the Balkans. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-31949-5.

- Winnifrith, Tom (2002). Badlands-borderlands: a history of Northern Epirus/Southern Albania. London: Duckworth. ISBN 0-7156-3201-9.

- Manta, Elevtheria (2005). Aspects of the Italian influence upon Greek - Albanian relations during the interwar period (Doctoral Dissertation) (in Greek). Aristotle University Of Thessaloniki. doi:10.12681/eadd/23718. hdl:10442/hedi/23718.

- Wilkes, John (1996). The Illyrians. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 0631198075.

- Konidaris, Gerasimos (2005). "Examining policy responses to immigration in the light of interstate relations and foreign policy objectives: Greece and Albania". In King, Russell; Mai, Nicola; Schwandner-Sievers, Stephanie (eds.). The New Albanian Migration. Sussex Academic Press. pp. 64–92. ISBN 978-1-903900-78-9.

Current topics

- Vickers, Miranda; Pettifer, James (1997). Albania: from anarchy to a Balkan identity. London: C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. ISBN 0-7156-3201-9.