Nolan Chart

The Nolan Chart is a political spectrum diagram created by American libertarian activist David Nolan in 1969, charting political views along two axes, representing economic freedom and personal freedom. It expands political view analysis beyond the traditional one-dimensional left–right/progressive-conservative divide, positioning libertarianism outside the traditional spectrum.

Development

The claim that political positions can be located on a chart with two axes: left–right (economics) and tough–tender (authoritarian-libertarian) was put forward by the British psychologist Hans Eysenck in his 1954 book The Psychology of Politics with statistical evidence based on survey data.[1] This leads to a loose classification of political positions into four quadrants, with further detail based on exact position within the quadrant.[2]

A similar two-dimensional chart appeared in 1970 in the publication The Floodgates of Anarchy by Stuart Christie and Albert Meltzer, but that work distinguished between the axes collectivism–capitalism on the one hand, individualism–totalitarianism on the other, with anarchism, fascism, "state communism" and "capitalist individualism" in the corners.[3] In Radicals for Capitalism (p. 321), Brian Doherty attributes the idea for the chart to an article by Maurice Bryson and William McDill in The Rampart Journal of Individualist Thought (Summer 1968) entitled "The Political Spectrum: A Bi-Dimensional Approach".[4]

Steve Mariotti, a teenage colleague of Carl Oglesby's in the leftist student organization Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), credits Oglesby with describing a form of the two-axis Nolan Chart during a delivery of Oglesby's "Let Us Shape the Future" speech[5] in 1965.[6] Oglesby's political outlook was more eclectic than that of many leftists in SDS; he was heavily influenced by libertarian economist Murray Rothbard and he dismissed socialism as "a way to bury social problems under a federal bureaucracy."[7] Oglesby even (unsuccessfully) proposed cooperation between SDS and the conservative group Young Americans for Freedom on some projects,[8] and argued that "in a strong sense, the Old Right and the New Left are morally and politically coordinate."[9] Nolan was a member of Young Americans for Freedom at the time.[10]

David Nolan first published his version of the chart in an article named "Classifying and Analyzing Politico-Economic Systems" in the January 1971 issue of The Individualist, the monthly magazine of the Society for Individual Liberty (SIL). In December 1971, he helped to start the group that would become the Libertarian Party.[11]

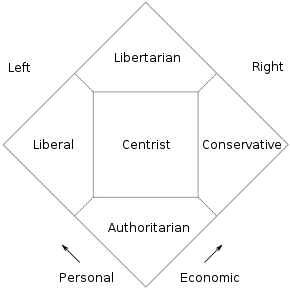

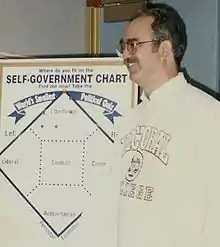

Frustrated by the "left-right" line analysis that leaves no room for other ideologies, Nolan devised a chart with two axes which would come to be known as the Nolan Chart, and later became the centerpiece of the World's Smallest Political Quiz. Nolan's argument was that the major difference between various political philosophies, the real defining element in what a person believes politically, is the amount of government control over human action that is advocated.[12] Nolan further reasoned that virtually all human political action can be divided into two broad categories: economic and personal. The "economic" category includes what people do as producers and consumers – what they can buy, sell and produce, where they work, who they hire and what they do with their money. Examples of economic activity include starting or operating a business, buying a home, constructing a building and working in an office. The "personal" category includes what people do in relationships, in self-expression and what they do with their own bodies and minds. Examples of personal activities include whom they marry; choosing what books they read and movies they watch; what foods, medicines and drugs they choose to consume; recreational activities; religious choices; organizations they join; and with whom they choose to associate.

According to Nolan, since most government activity (or government control) occurs in these two major areas, political positions can be defined by how much government control a person or political party favors in these two areas. The extremes are no government at all in either area (anarchism) or total or near-total government control of everything (various forms of totalitarianism). Most political philosophies fall somewhere in between. In broad terms:

- Those on the right, including American conservatives, tend to favor more freedom in economic matters (example: a free market), but more government intervention in personal matters (example: drug laws).

- Those on the left, including American liberals, tend to favor more freedom in personal matters (example: no military draft), but more government activism or control in economics (example: a government-mandated minimum wage).

- Libertarians favor both personal and economic freedom and oppose most (or all) government intervention in both areas. Like conservatives, libertarians believe in free markets. Like liberals, libertarians believe in personal freedom.

- Authoritarians favor a lot of government control in both the personal and economic areas. Different versions of the chart as well as Nolan's original chart use terms such as "totalitarian", "statist", "communitarian" or "populist" to label this corner of the chart.

- Centrists favor a balance or mix of both freedom and government involvement in both personal and economic matters.

In order to visually express this argument, Nolan came up with a two-axis graph. One axis was for economic freedom and the other was for personal freedom, with the scale on each of the two axes ranging from zero (total state control) to 100% (no state control). 100% freedom in economics would mean an entirely free market (laissez-faire); 100% freedom in personal issues would mean no government control of private, personal life. By using the scale on each of the two axes, it was possible to graph the intersection of the amount of personal liberty and economic liberty a person, political organization, or political philosophy advocates. Therefore, instead of classifying all political opinion on a one-dimensional range from left to right, Nolan's chart allowed two-dimensional measurement: how much (or little) government control a person favored in personal and economic matters.

Nolan said that one of the impacts of his chart is that when someone views it, it causes an irreversible change as viewers henceforth view the included orientations in two dimensions instead of one.[13]

In 1987, Marshall Fritz, founder of Advocates for Self-Government, tweaked the chart and added ten questions – which he called the World's Smallest Political Quiz – which enabled people to plot their political beliefs on the chart.[14]

Positions

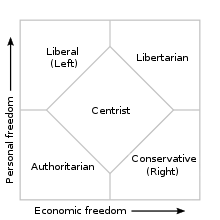

Differing from the traditional left–right distinction and other political taxonomies, the Nolan Chart in its original form has two dimensions, with a horizontal x-axis labeled "economic freedom" and a vertical y-axis labeled "personal freedom". It resembles a square divided into five sections, with a label assigned to each of the following sections:

- Bottom left – Statism. The opposite of libertarianism, corresponding with those supporting low economic and personal freedom.[15][16]

- Top left – Left-wing political philosophies. Those supporting low economic freedom and high personal freedom.

- Bottom right – Right-wing political philosophies. Those supporting high economic freedom and low personal freedom.

- Top right – Libertarians. David Nolan's own philosophy, corresponding with those supporting high economic and personal freedom.

- Center – Centrism. The center area defines the political middle, for those who favor a mixed system balancing both economic and personal freedom with the need for some market regulation and personal sacrifice.

Polling

In August 2011, the libertarian Reason magazine worked with the Rupe organization to survey 1,200 Americans by telephone and place their views within the Nolan chart categories. The Reason-Rupe poll found that "Americans cannot easily be bundled into either the 'liberal' or 'conservative' groups". Specifically, 28% expressed conservative views, 24% expressed libertarian views, 20% expressed communitarian views and 28% expressed liberal views. The margin of error was ±3.[17]

Criticism

Brian Patrick Mitchell, who uses a different political taxonomy, cites these points of disagreement:[18]

- The strict separation of social and economic policy that the chart is based on, is untenable in general. In migration policy, for example, both sociocultural and economic issues are at play.

- The view that the Right can be defined by its acceptance of state intervention into the domestic sphere (little 'personal freedom') and the Left by its rejection, is false. In the U.S., the Right generally opposed gun control, while the Left argues for it.

Similar criticisms, but from a libertarian perspective, are leveled by Jacob Huebert,[19] who adds that the separation of personal and economic liberty is untenable when one considers the rights to prostitute oneself and to deal drugs, both of which are libertarian causes: adopting either profession is a personal (moral) as well as an economic decision. Also, Huebert notes that it is unclear where in the Nolan chart libertarian opposition to war belongs.

The libertarian response to these criticisms is that the issues are presented in a specific frame of reference by the political factions consistent with the chart. Free immigration is typically viewed as a personal liberty issue, so it is favored by those on the political left.[20] Drug legalization is framed as a personal rights issue, so it tends to be favored by the left.[21] War is viewed as a destruction of both society[22] and the economy.[23]

Further applications

Some commentators have accepted Nolan's use of two axes of personal and economic freedom, but have argued that he either didn't go far enough or that the Nolan Chart can be used to demonstrate the validity of other ideologies. For example, Kelley L. Ross, a libertarian former philosophy professor who ran for California State Assembly in 1996,[24] contends that a third axis of political liberty is required to make the chart more meaningful.[25] On the other hand, Owen Prell, a founding member of Unite America, formerly The Centrist Project,[26] contends that the Nolan Chart is a definite improvement on the more primitive single-axis left-right political continuum, but that it better serves the cause of political centrism.[27][28]

Several popular online tests, where individuals can self-identify their political values, utilize the same two axes as the Nolan Chart without attribution, including The Political Compass, iSideWith.com and MapMyPolitics.org.[29]

References

- Hans Eysenck. The Psychology of Politics. 1954.

- David Claborn & Lindsey Tobias. "If You Can't Join 'Em, Don't : Untangling Attitudes on Social, Economic and Foreign Issues by Graphing Them". Olivet Nazarene University. Retrieved May 15, 2015.

- Christie, Stuart, Albert Meltzer. The Floodgates of Anarchy. Kahn & Averill. London. 1970. p. 73. ISBN 978-0900707032.

- Maurice Bryson, William McDill (Summer 1968). "The Political Spectrum: A Bi-Dimensional Approach" (PDF). The Rampart Journal of Individualist Thought.

- Students For A Democratic Society (SDS), Document Library, Let Us Shape the Future, By Carl Oglesby, November 27, 1965

- Steve Mariotti (23 October 2013). "Economically Conservative Yet Socially Tolerant? Find Yourself on the Nolan Chart". Huffington Post.

- Kauffman, Bill (2008-05-19) When the Left Was Right, The American Conservative.

- Bill Kauffman, "Writer on the Storm," Reason, April 2008 (September 10, 2008).

- McCarthy, Daniel (2010-02-24) Carl Oglesby Was Right, The American Conservative.

- Rebecca E. Klatch, A Generation Divided: The New Left, the New Right, and the 1960s, University of California Press, 1999 ISBN 0520217144, 215–237.

- "David Nolan – Libertarian Celebrity". Advocates for Self Government. Archived from the original on June 16, 2008. Retrieved September 9, 2008.

- "About the Quiz".

- "Mark Selzer and co-host Martina Slocomb interview David Nolan". The Libertarian Alternative Public Access TV Show. Retrieved February 15, 2013.

- "World's Smallest Political Quiz Taken 21 Million Times Online". 22 February 2014.

- "The ORIGINAL and Acclaimed Internet Political Quiz!". Advocates For Self-Government. Retrieved June 4, 2018.

- "What is a Statist?". Nolan Chart – Online Marketing Guild LLC. Retrieved June 4, 2018.

- Emily Ekins (August 29, 2011). "Reason-Rupe Poll Finds 24 Percent of Americans are Economically Conservative and Socially Liberal, 28 Percent Liberal, 28 Percent Conservative, and 20 Percent Communitarian". Reason. Retrieved January 1, 2012.

- Brian Patrick Mitchell (2007). Eight Ways to Run the Country: A New and Revealing Look at Left and Right. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 7. ISBN 978-0275993580.

- H., Huebert, Jacob (2010). Libertarianism today. Santa Barbara, Calif.: Praeger. pp. 22–24. ISBN 978-0313377556. OCLC 655885097.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Conor Friedersdorf (2014). "How Immigration Can Restrict and Enhance Liberty".

- Emily Dufton (2012). "The War on Drugs: Should It Be Your Right to Use Narcotics?".

- Madison West (2013). "The Problem Is War".

- Tejvan Pettinger (2019). "Economic impact of war".

- Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: "Dr. Kelley L. Ross Debates". YouTube. 26 March 2013. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- "Positive and Negative Liberties in Three Dimensions". 3 June 2020. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- "Centrist Project, which backed Pressler in 2014, looks ahead". Capital Journal. 3 January 2016.

- Sherman, Roger (8 April 2017). "Fixing American Politics – A Reformer's Memo from Kansas City". Medium.

- Prell, Owen (25 March 2020). "We Are All Centrists Now". Medium.

- LiCalzi O'Connell, Pamela (4 December 2003). "Online Diary". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

Further reading

- Bryson, Maurice C.; McDill, William R. (Summer 1968). "The Political Spectrum: A Bi-Dimensional Approach" (PDF). Rampart Journal of Individualist Thought. Larkspur, CO: Rampart College. IV: 19–26.

External links

- A modern version of the Nolan Chart

- Nolan Chart website

- The Nolan Chart and its variations

- Positive & Negative Liberties in Three Dimensions

- The Enhanced Precision Political Quiz... IN 2D

- Political Profile Test

- Political Spectrum Quiz

- A voting index of the U.S. Congress (prepared by Prof. Clifford F. Thies for the Republican Liberty Caucus)