New Forest pony

The New Forest pony is one of the recognised mountain and moorland or native pony breeds of the British Isles.[1] Height varies from around 12 to 14.2 hands (48 to 58 inches, 122 to 147 cm); ponies of all heights should be strong, workmanlike, and of a good riding type. They are valued for hardiness, strength, and sure-footedness.

New Forest pony at Spy Holms | |

| Country of origin | England |

|---|---|

| Traits | |

| Distinguishing features | Very sturdy with plenty of speed, can be ridden by children or adults, all colours are acceptable except piebald, skewbald, and blue-eyed cream, but most are bay, chestnut, or grey |

| Breed standards | |

The breed is indigenous to the New Forest in Hampshire in southern England, where equines have lived since before the last Ice Age; remains dating back to 500,000 BC have been found within 50 miles (80 km) of the heart of the modern New Forest. DNA studies have shown ancient shared ancestry with the Celtic-type Asturcón and Pottok ponies. Many breeds have contributed to the foundation bloodstock of the New Forest pony, but today only ponies whose parents are both registered as purebred in the approved section of the stud book may be registered as purebred. The New Forest pony can be ridden by children and adults, can be driven in harness, and competes successfully against larger horses in horse show competition.

All ponies grazing on the New Forest are owned by New Forest commoners – people who have "rights of common of pasture" over the Forest lands. An annual marking fee is paid for each animal turned out to graze. The population of ponies on the Forest has fluctuated in response to varying demand for young stock. Numbers fell to fewer than six hundred in 1945, but have since risen steadily, and thousands now run loose in semi-feral conditions. The welfare of ponies grazing on the Forest is monitored by five Agisters, employees of the Verderers of the New Forest. Each Agister takes responsibility for a different area of the Forest. The ponies are gathered annually in a series of drifts, to be checked for health, wormed, and they are tail-marked; each pony's tail is trimmed to the pattern of the Agister responsible for that pony. Purebred New Forest stallions approved by the Breed Society and by the New Forest Verderers run out on the Forest with the mares for a short period each year. Many of the foals bred on the Forest are sold through the Beaulieu Road pony sales, which are held several times each year.

Characteristics

Standards for the breed are stipulated by the New Forest Pony Breeding and Cattle Society. The maximum height allowed is 14.2 1⁄4 hands (58.25 inches, 148 cm). Although there is no minimum height standard, in practice New Forest ponies are seldom less than 12 hands (48 inches, 122 cm). In shows, they normally are classed in two sections: competition height A, 138 centimetres (54 in) and under; and competition height B, over 138 centimetres (54 in). New Forest ponies should be of riding type, workmanlike, and strong in conformation, with a sloping shoulder and powerful hindquarters; the body should be deep, and the legs straight with strong, flat bone, and hard, rounded hooves.[2] Larger ponies, although narrow enough in the barrel for small children to ride comfortably, are also capable of carrying adults. Smaller ponies may not be suitable for heavier riders, but they often have more show quality. The New Forest pony has free, even gaits, active and straight, but not exaggerated, and is noted for sure-footedness, agility, and speed.[3]

The ponies are most commonly bay, chestnut, or grey. Few coat colours are excluded: piebald, skewbald, and blue-eyed cream are not allowed; palomino and very light chestnut are only accepted by the stud book as geldings and mares. Blue eyes are never accepted. White markings on the head and lower legs are allowed, unless they appear behind the head, above the point of the hock in the hind leg, or above the metacarpal bone at the bend in the knee in the foreleg.[2] Ponies failing to pass these standards may not be registered in the purebred section of the stud book, but are recorded in the appendix, known as the X-register. The offspring of these animals may not be registered as purebred New Forest ponies, as the stud book is closed and only the offspring of purebred-approved registered ponies may be registered as purebred.[2][4]

New Forest ponies have a gentle temperament and a reputation for intelligence, strength, and versatility.[3] On the whole, they are a sturdy and hardy breed.[5] The one known hereditary genetic disorder found in the breed is congenital myotonia, a muscular condition also found in humans, dogs, cats, and goats. It was identified in the Netherlands in 2009, after a clinically affected foal was presented to the Equine Clinic of Utrecht University. DNA sequencing revealed that the affected foal was homozygous for a missense mutation in the gene encoding CLCN1, a protein which regulates the excitability of the skeletal muscle.[6][7] The mutated allele was found in both the foal's parents, its siblings, and two other related animals, none of whom exhibited any clinical signs. The researchers concluded that the condition has an autosomal recessive mode of inheritance, whereby both parents have to contribute the mutated allele for a physically affected foal to be produced with that phenotype. The study suggested that the mutation was of relatively recent origin: the founder of the mutated gene, as all the ponies who tested positive for the mutation are direct descendants of this stallion.[6][8] The probable founder stallion has been identified as Kantje's Ronaldo; testing is now underway to identify which of his offspring carry the mutated gene. All carriers will be removed from the breeding section of the New Forest Pony Breeding & Cattle Society's stud book, and all New Forest stallions licensed in the UK also will be tested, whether or not they descend from Kantje's Ronaldo, to cover the possibility that the mutated gene may have appeared earlier in the pedigree, although it is believed that the mutated gene has now been eradicated from the British breeding stock. All breeding stock imported to the UK also will be tested.[9]

History

Ponies have grazed in the area of the New Forest for many thousands of years, predating the last Ice Age.[10] Spear damage on a horse shoulder bone discovered at Eartham Pit, Boxgrove (about 50 miles (80 km) from the heart of the modern New Forest), dated 500,000 BC, demonstrates that early humans were hunting horses in the area at that time,[11] and the remains of a large Ice Age hunting camp have been found close to Ringwood (on the western border of the modern New Forest).[12] Evidence from the skeletal remains of ponies from the Bronze Age suggests that they resembled the modern Exmoor pony.[13] Horse bones excavated from Iron Age ritual burial sites at Danebury (about 25 miles (40 km) from the heart of the modern New Forest),[14] indicate that the animals were approximately 12 hands (48 inches, 122 cm)[15] – a height similar to that of some of the smaller New Forest ponies of today.

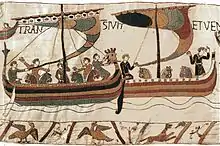

William the Conqueror, who claimed the New Forest as a royal hunting ground,[16] shipped more than two thousand horses across the English Channel when he invaded England in 1066.[17][18] The earliest written record of horses in the New Forest dates back to that time, when rights of common of pasture were granted to the area's inhabitants.[19] A popular tradition linking the ancestry of the New Forest pony to Spanish horses said to have swum ashore from wrecked ships at the time of the Spanish Armada has, according to the New Forest National Park Authority, "long been accepted as a myth",[20] however, the offspring of Forest mares, probably bred at the Royal Stud in Lyndhurst, were exported in 1507 for use in the Renaissance wars.[10] A genetic study in 1998 suggested that the New Forest pony has ancient shared ancestry with two endangered Spanish Celtic-type pony breeds, the Asturcón and Pottok.[21][22]

The most notable stallion in the early history of the breed was a Thoroughbred named Marske, the sire of Eclipse, and a great-grandson of the Darley Arabian.[23] Marske was sold to a Ringwood farmer for 20 guineas on the death of Prince William, Duke of Cumberland, and was used to breed with "country mares" in the 1760s.[10][24]

In the 1850s and 1860s, the quality of the ponies was noted to be declining, a result of poor choice of breeding stallions, and the introduction of Arab to improve the breed was recommended. The census of stock of 1875 reported just under three thousand ponies grazing the Forest, and by 1884 the number had dropped to 2,250. Profits from the sale of young ponies affected the number of mares that commoners bred in subsequent years. The drop in numbers on the Forest may have been a consequence of introducing Arab blood to the breed in the 1870s, resulting in fewer animals suitable for use as pit ponies, or to the increase in the profits from running dairy cattle instead of ponies. The Arab blood may have reduced the ponies' natural landrace hardiness to thrive on the open Forest over winter. Numbers of ponies on the Forest also declined as a result of demand for more refined-looking ponies for riding and driving work prior to the introduction of motor vehicles. Later, the Second World War drove up the demand for, and thus, the market value of, young animals for horse meat.[25]

Founded in 1891, the Society for the improvement of New Forest Ponies organised a stallion show and offered financial incentives to encourage owners of good stallions to run them on the Forest.[26] In 1905 the Burley and District NF Pony Breeding and Cattle Society was set up to start the stud book and organise the Breed Show;[10] the two societies merged in 1937 to form the New Forest Pony Breeding and Cattle Society.[27] Overall numbers of livestock grazing the Forest, including ponies, tended to decline in the early twentieth century; in 1945 there were just 571 ponies depastured.[28] By 1956 the number of ponies of all breeds on the Forest had more than doubled to 1,341. Twenty years later pony numbers were up to 3,589, rising to 4,112 in 1994, before dipping back below four thousand until 2005. As of 2011, there were 4,604 ponies grazing on the New Forest.[29]

In 2014, the Rare Breeds Survival Trust (RBST) conservation charity watch-listed the New Forest pony in its "minority breed" category, given the presence of less than 3,000 breeding females in the forest. Over the course of five years, the number of foals born each year had dropped by two-thirds (from 1,563 to just 423 in 2013) – a change attributed by The New Forest Pony Breeding and Cattle Society to a declining market, and by the New Forest Verderers to steps that had been taken to improve the quality rather than the quantity of foals.[30]

For a variety of reasons, including normal trade in the area and attempts to improve the breed, Arabian, Thoroughbred, Welsh pony, and Hackney blood had been added to ponies in the New Forest.[31] Over time, however, the better-quality ponies were sold off, leaving the poorer-quality and less hardy animals as the Forest breeding stock.[10] To address this situation, as well as to increase the stock's hardiness and restore native type, in the early twentieth century animals from other British native mountain and moorland pony breeds such as the Fell, Dales, Highland, Dartmoor, and Exmoor were introduced to the Forest.[31] This practice ended in 1930, and since that time, only purebred New Forest stallions may be turned out.[10] The New Forest Pony Breeding and Cattle Society has been publishing the stud book since 1960. New Forest ponies have been exported to many parts of the world, including Canada, the U.S., Europe, and Australia,[26] and many countries now have their own breed societies and stud books.[32]

Uses

In the past, smaller ponies were used as pit ponies.[25] Today the New Forest pony and related crossbreeds are still the "working pony of choice" for local farmers and commoners, as their sure-footedness, agility, and sound sense will carry them (and their rider) safely across the varied and occasionally hazardous terrain of the open Forest, sometimes at great speed, during the autumn drifts.[3] New Forest ponies also are used today for gymkhanas, show jumping, cross-country, dressage, driving, and eventing.[33]

The ponies can carry adults and in many cases compete on equal terms with larger equines while doing so. For example, in 2010, the New Forest Pony Enthusiasts Club (NFPEC), a registered riding club whose members compete only on purebred registered New Forest ponies, won the Quadrille competition at the London International Horse Show at Olympia.[34] This was a significant win, as the British Riding Clubs Quadrille is a national competition, with only four teams from the whole of Britain selected to compete at the National Final.[35][36]

Ponies on the New Forest

The ponies grazing the New Forest are considered to be iconic. They, together with the cattle, donkeys, pigs, and sheep owned by commoners' (local people with common grazing rights), are called "the architects of the Forest": it is the grazing and browsing of the commoners' animals over a thousand years which created the New Forest ecosystem as it is today.[37]

The cattle and ponies living on the New Forest are not completely feral, but are owned by commoners, who pay an annual fee for each animal turned out.[38] The animals are looked after by their owners and by the Agisters employed by the Verderers of the New Forest. The Verderers are a statutory body with ancient roots, who share management of the forest with the Forestry Commission and National park authority.[39][40] Approximately 80 per cent of the animals depastured on the New Forest are owned by just 10 per cent of the commoning families.[41]

Ponies living full-time on the New Forest are almost all mares, although there are also a few geldings. For much of the year the ponies live in small groups, usually consisting of an older mare, her daughters, and their foals, all keeping to a discrete area of the Forest called a "haunt." Under New Forest regulations, mares and geldings may be of any breed. Although the ponies are predominantly New Foresters, other breeds such as Shetlands and their crossbred descendants may be found in some areas.[5]

Stallions must be registered New Foresters, and are not allowed to run free all year round on the Forest. They normally are turned out only for a limited period in the spring and summer, when they gather several groups of mares and youngstock into larger herds and defend them against other stallions. A small number (usually fewer than 50) are turned out,[42] generally between May and August. This ensures that foals are born neither too early (before the spring grass is coming through), nor too late (as the colder weather is setting in and the grazing and browsing on the Forest is dying back) in the following year.[43]

Colts are assessed as two-year-olds by the New Forest Pony Breeding and Cattle Society for suitability to be kept as stallions; any animal failing the assessment must be gelded. Once approved, every spring (usually in March), the stallions must pass the Verderers' assessment before they are permitted onto the Forest to breed.[42] The stallion scheme resulted in a reduction of genetic diversity in the ponies running out on the New Forest, and to counteract this and preserve the hardiness of Forest-run ponies, the Verderers introduced the Bloodline Diversity Project, which will use hardy Forest-run mares, mostly over eleven years old, bred to stallions that have not been run out on the Forest, or closely related to those that have.[44]

Drifts to gather the animals are carried out in autumn. Most colts and some fillies are removed, along with any animals considered too "poor" to remain on the Forest over the winter. The remaining fillies are branded with their owner's mark, and many animals are wormed.[45][46] Many owners choose to remove a number of animals from the Forest for the winter, turning them out again the following spring.[47] Animals surplus to their owner's requirements often are sold at the Beaulieu Road Pony Sales, run by the New Forest Livestock Society.[48] Tail hair of the ponies is trimmed, and cut into a recognisable pattern to show that the pony's grazing fees have been paid for the year. Each Agister has his own "tail-mark", indicating the area of the Forest where the owner lives.[49] The Agisters keep a constant watch over the condition of the Forest-running stock, and an animal may be "ordered off" the Forest at any time.[38] The rest of the year, the lives of the ponies are relatively unhindered unless they need veterinary attention or additional feeding, when they are usually taken off the Forest.[50]

The open nature of the New Forest means that ponies are able to wander onto roads.[51] The ponies actually have right of way over vehicles and many wear reflective collars in an effort to reduce traffic fatalities,[52] but despite this, many ponies, along with commoners' cattle, pigs, and donkeys are killed or injured in road traffic accidents every year.[51] Human interaction with ponies is also a problem; well meaning but misguided visitors to the forest frequently feed them, which can create dietary problems and sickness (e.g. colic) and cause the ponies to adopt an aggressive attitude in order to obtain human food.[53]

New Forest ponies are raced in an annual point to point meeting in the Forest, usually on Boxing Day, finishing at a different place each year.[54][55] The races do not have a fixed course, but instead are run across the open Forest, so competitors choose their own routes around obstructions such as inclosures (forestry plantations), fenced paddocks, and bogs. Riders with a detailed knowledge of the Forest are thus at an advantage. The location of the meeting place is given to competitors on the previous evening, and the starting point of the race is revealed once riders have arrived at the meeting point.[54]

References

- Winter, Dylan (presenter) (20 January 2006). "Fit for the future". Rare steeds. Episode 5. BBC. Radio 4. Retrieved 9 June 2012.

- "Breed Standards for The New Forest Pony". The New Forest Pony Breeding and Cattle Society. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- Fear 2006, p. 29.

- "Registration and Passport Information". The New Forest Pony Breeding & Cattle Society. 2011. Retrieved 10 May 2012.

- "History and heritage: New Forest ponies" (PDF). Forestry Commission. 2004. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- Wijnberg, I.D.; Owczarek-Lipska, M.; Sacchetto, R.; Mascarello, F.; Pascoli, F.; Grünberg, W.; van der Kolk, J.H.; Drögemüller, C. (April 2012). "A missense mutation in the skeletal muscle chloride channel 1 (CLCN1) as candidate causal mutation for congenital myotonia in a New Forest pony". Neuromuscular Disorders. 22 (4): 361–7. doi:10.1016/j.nmd.2011.10.001. PMID 22197188. S2CID 8292200.

- "Myotonia. Phenotype in horse (Equus caballus)". OMIA. Archived from the original on 13 December 2012. Retrieved 15 June 2012.

- Utrecht University Press Communications (27 March 2012). "Myotonia discovered in New Forest ponies". Utrecht University. Retrieved 13 June 2012.

- "Myotonia". New Forest Pony Breeding & Cattle Society. November 2012. Archived from the original on 8 March 2013. Retrieved 3 January 2013.

- "History of The New Forest Pony Breed". The New Forest Pony Breeding and Cattle Society. 2011. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- Roberts, Mark (October 1996). "Man the Hunter returns at Boxgrove". British Archaeology (18). Retrieved 9 June 2012.

- "Ice Age hunting camp found in Hampshire". British Archaeology (61). October 2001. Retrieved 9 June 2012.

- Osgood, Richard (July 1999). "Britain in the age of warrior heroes". British Archaeology (46). Retrieved 9 June 2012.

- Green, Miranda (1998). Animals in Celtic Life and Myth. Routledge. pp. 115–116. ISBN 978-0-415-18588-2.

- Grimm, Jessica M. (2008). Archaeology on the A303 Stonehenge Improvement; Appendix 6 – Animal bones (PDF) (from report). Wessex Archaeology. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 July 2013. Retrieved 9 June 2012.

- "History of the New Forest". New Forest National Park Authority. 2009. Archived from the original on 13 October 2009. Retrieved 26 May 2012.

- Hyland, Ann (1994). The Medieval Warhorse: From Byzantium to the Crusades. Grange Books. p. 99. ISBN 978-1-85627-990-1.

- Morillo, Stephen (1996). The Battle of Hastings: Sources and Interpretation. Boydell. p. 222. OCLC 60237653.

- Fear 2006, p. 91.

- "New Forest wildlife". New Forest National Park Authority. 2006. Archived from the original on 13 October 2009. Retrieved 26 May 2012.

- Checa, M.L; Dunner, S.; Martin, J.P.; Vega, J.L.; Cañon, J. (1998). "A note on the characterization of a small Celtic pony breed". Journal of Animal Breeding and Genetics. 115 (1–6): 157–163. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0388.1998.tb00339.x. ISSN 0931-2668.

- Aberle, Kerstin S.; Distl, Ottmar (2004). "Domestication of the horse: results based on microsatellite and mitochondrial DNA markers" (PDF). Archiv für Tierzucht. 47 (6): 517–535. Retrieved 19 April 2012.

- "Marske". Thoroughbred Bloodlines. Retrieved 19 April 2012.

- Peters, Anne. "Eclipse". Thoroughbred Heritage. Retrieved 19 April 2012.

- Tubbs 1965, pp. 37–38.

- "History". New Forest Pony Association (USA). 15 December 1992. Archived from the original on 16 January 2012. Retrieved 19 April 2012.

- Ivey, p. 11.

- Tubbs 1965, pp. 38–39.

- "Stock turned out onto the Forest" (PDF). Verderers of the New Forest. 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 March 2012. Retrieved 19 April 2012.

- "New Forest pony listed as rare breed". BBC News online, Hampshire & Isle of Wight. 20 February 2014. Retrieved 20 February 2014.

- "About the Breed". The New Forest Pony Breeding and Cattle Society. Retrieved 19 April 2012.

- See for example: USA, New Forest Pony Association & Registry; Australia, New Forest Pony Association of Australia; Belgium, Newforestpony Belgium; Norway, Norsk Ponniavlsforening – New Forest (in Norwegian); Sweden, The Swedish New Forest Pony Society Archived 2010-08-11 at the Wayback Machine ; Denmark, Newforest.dk (in Danish); Netherlands, Nederlands New Forest Pony Stamboek (in Dutch); Finland, Suomen New Forest Poniyhdistys (in Finnish). All retrieved 15 June 2012.

- "The New Forest Pony Breeding and Cattle Society". The New Forest Pony Breeding and Cattle Society. Archived from the original on 29 January 2009. Retrieved 29 December 2011.

- "Winning Olympia Quadrille". The New Forest Pony Breeding and Cattle Society. 18 December 2010. Archived from the original on 15 April 2012. Retrieved 19 April 2012.

- "Dressage to Music and Quadrille information". The British Horse Society. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- 2010 Quadrille Final Olympia on YouTube (from British Riding Clubs, britishridingclubs.org.uk). Retrieved 9 June 2012.

- "The New Forest Pony". New Forest National Park Authority. 2012. Archived from the original on 6 December 2011. Retrieved 7 June 2012.

- Fear 2006, p. 75.

- Fear 2006, p. 72.

- "Who runs the National Park?". New Forest National Park Authority. 2012. Retrieved 13 May 2018.

- Fear 2006, p. 22.

- Fear 2006, p. 96.

- "Animal welfare organisations praise condition of Forest ponies". Verderers of the New Forest. 2004. p. 2. Retrieved 7 May 2012.

- "Newsletter" (PDF). Verderers of the New Forest. February 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 July 2013. Retrieved 7 June 2012.

- Fear 2006, pp. 49–54.

- Fear 2006, p. 79.

- Fear 2006, p. 24.

- Fear 2006, p. 59.

- Fear 2006, p. 116.

- Ivey, p. 9.

- "Animal accidents". New Forest National Park Authority. 2012. Archived from the original on 14 May 2018. Retrieved 13 May 2018.

- "Animal accidents: How you can help". New Forest National Park Authority. 2013. Archived from the original on 10 October 2011. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- "Feeding and petting ponies". New Forest National Park Authority. 2013. Archived from the original on 10 October 2011. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- Ivey, p. 32.

- Fear 2006, p. 70.

Bibliography

- Fear, Sally (2006). New Forest Drift: A Photographic Portrait of Life in the National Park. Perspective Photo Press. ISBN 978-0-9553253-0-4.

- Ivey, Jo. "Report on New Forest traditions" (PDF). Our New Forest: a living register of language and traditions. New Forest Museum. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 March 2013. Retrieved 9 June 2012.

- Tubbs, C.R. (1965). "The Development of the Smallholding and Cottage Stock-keeping Economy of the New Forest". The Agricultural History Review. 13 (1): 23–39. Retrieved 19 April 2012.

External links

- The New Forest Pony Breeding and Cattle Society

- The Verderers of the New Forest

- New Forest Livestock Society

- New Forest National Park Information

- New Forest Pony Association (USA)

- New Forest Pony Society of North America

- New Forest Pony Association of Australia

- New Forest Pony Owners and Breeders of Australia

- New Forest Pony, Norway

- The Swedish New Forest Pony Society

- The Danish New Forest Pony Society

- Netherlands New Forest Pony Studbook

- New Forest Pony Society of Finland