Nding language

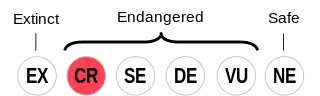

Nding is a (critically) endangered[2][3] Niger–Congo language in the Talodi family of Kordofan, Sudan.[4]

| Nding | |

|---|---|

| Eliri | |

| Native to | Sudan |

| Region | Eliri Hills, Mountain Jebel Eliri, South Talodi in the South Kordofan |

| Ethnicity | Eliri people |

| Extinct | Threatened/Critically Endangered[1] |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | eli |

| Glottolog | ndin1245 |

| ELP | Nding |

Nding is a critically endangered language according to the classification system of the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger | |

General information

Nding is spoken in the area of the mountain (Jebel) Eliri, on the south of Talodi in South Kordofan, Sudan.[4][5] Because of that, the language also goes by the name Eliri.

According to the UNESCO “Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger” from 2010, the language is critically endangered.[2] However, the 2020 edition of "Ethnoloɠue" describes it as endangered, counting 400 speakers among some young people and all adults.[3]

Phonetics

Vowels

In the Nding language, exist the following vowels: a, e, i, o, u. Among those a, e, o, can be further classified as long or short, pronunciation-wise.[4]

Consonants

In the Nding language, appear following consonants: k, g, ṅ, tj, dj, ń, t, d, n, r, l, y, p, b, m, w.[4] Interestingly, the sound “h” is absent in the Nding phonetics.[4] These consonants can get nasalized by connecting one consonant with n or m; and in some cases, also with their various parallel forms, e.g. ṅg (alternatively ńg/ṅń), ndj (alternatively ṅdj/ńdj), nd, mb.[4] Rarely does one come across such combinations as rn, rb, dr.[4]

The consonant “l” [el] can, and often is, also written as “il”.[4]

Consonant and vowel changes

Words can change from voiceless to voiced if the preceding word ends with “n”. For example, tetjo [eng. house] in the sentence “the man departs from the house” becomes detjo: babura ako an detjo.[4] Such consonant and vowel changes also seem to happen in an irregular manner, as there is no obvious connection found yet, e.g. tj becomes dj, ti becomes di, ta becomes da.[4]

Tonality

There is no evidence of tones in Nding.[4]

Grammar

Sentence structure

The most widespread sentence structure seems to be Subject→Verb→Object, however, the use of Verb→Object→Subject has been documented as well.[4] Personal pronouns come before the verb.[4] Prepositions such as “what” (Nding: yara), “where” (Nding: ča) and “who” (Nding: abura) come at the beginning of the sentence.[5] Important is the fact that the noun doesn’t change, no matter its usage, e.g. the noun being a subject/an object/when it comes together with a preposition, has no influence on its form.[5]

Nouns

Nouns seem to be mostly voiceless, but when they become adjectives, they usually (but not always) become voiced, e.g. p becomes b, tj becomes dj.[4]

Genus

Gender of a noun is signaled in Nding through prefixes.[4] For more information, see the paragraph below.

Plural forms

The plural form is created through a change of the initial sound of the noun and it depends on the gender-bound prefix, that the noun possesses.[4][5] That can mean a change of the prefix or a change of the final position of the word.[4] The before-mentioned categories stand at the core of Meinhof’s plural form classification. First, I’ll talk about the prefix-changing building of the plural form. There are the following subcategories of these nouns, according to Meinhof:[4]

1. sing. b- pl. y- (e.g. sing. baà pl. ya [eng. a man]) and sing. p- pl. – (e.g. sing. pali pl. ali [eng. a pot])

2. sing. dj- tj- t- pl. m- (e.g. sing. tino pl. mino [eng. a rock, stone])

3. sing. t- pl. r- or n-

4. sing. g- or – pl. ṅ- (attention! sing. ṅu- pl. ṅa-)

5. sing. tje- and – pl. kā-

6. sing. k- pl. –

Now, the other type of plural form, created by a change of the final position, is categorized in the following way:[4]

1. sing. -ak or -k pl. a- or –

Oftentimes vowel changes appear in plural forms too, e.g. nudruba pl. nuduruba [eng. rabbit].[4]

Plural forms can also change their stems and be irregular, e.g. sing. bwai pl. tje [eng. cow/cows].[4]

Adjectives

The information and data gathered on the topic of adjectives are very limited, and according to Seligmann, in Nding they would be usually replaced with a verbal construction, e.g. instead of saying “no mountain is greater than Eliri” it would be literally translated as “no mountain surpasses Eliri”= ko ma keñe Dayo[5].

The initial sound of an adjective adapts to the initial sound of the noun, to which it refers to, and they change in their plural forms accordingly.[4] Meinhof divided the adjectival noun-dependent prefixes into 3 categories:[4]

1. sing. b- and p- pl. y- or – (e.g. -abuya [eng. full]→ sing. pali babuya pl. ali yabuya [eng. a full pot/full pots])

2. sing. -ōte [eng. good] (e.g. sing. tjalaṅga djōte pl. malanga mōte [eng. a good leg/good legs]). Here one can also notice how the tj- and dj- prefixes have the same, beforementioned plural prefix form m-

3. -akonda [eng. broken] (e.g. sing. guri kakonda pl. nuri nakonda/e). Attention to exceptions; As one can see, the adjective and the noun in the singular form don’t fit exactly (g and k) but in the plural, they both start with the same letter (n)

Grammatical Cases (Kasus)

The genitive seems very rare and almost non-existent in the Nding language, however, when it is used, it is put at the end of the phrase unit, just like in Bantu, e.g. ba bura bá Dayo [eng. an Eliri man/a man from Eliri].[4]

Numerals

| Numeral | Nding translation |

|---|---|

| 1 | elle |

| 2 | eta |

| 3 | etak |

| 4 | yibinik |

| 5 | tjebiṅgela |

| 6 | menayelle |

| 7 | menayeta |

| 8 | menayélak |

| 9 | menayíbinik |

| 10 | yemeńunok |

| 11 | yemeńunok menayella |

| 20 | yemenyalok yemenyalok |

The numerals 1,2 and 3 with connection to the -mena (see numbers 6, 7, 8) gain an initial sound -y. It is being theorized, that -mena means something like “add”.[4] Additionally, the number 10 (yemeńunok) and the repeated "yemenyalok" in the number 20, are thought to be the same word (ń→ny and u→a).[4]

Personal pronouns

Normal personal pronouns: aṅi (I), aṅo (you), aṅo (he), arnaṅo (we), ata (they).[4]

Personal pronouns before the verb: ńi/ṅi/ni (I), aṅo (you), aṅo (he), ṅori/ari (we), ṅorno/ano (you pl.), ṅota/ӑtӑ (she).[4]

Personal pronouns can also conjoin with the verbs and act as suffixes; thus, indicating the subject of the action: -ia/i (I), -wa/o (you), -wa/oba (he), -uria/-ori (we), -ota/-ata (you pl.), -una/-ata (she).[4] When that happens, the stem of the word can change (esp. the vowels a, o, u have a tendency to swap).[4] Nevertheless, there are many ambiguities and contradictions in the data about personal pronouns, so there are still many problems with finding a clear pattern.[4]

Possessive pronouns

Personal pronouns: i/iṅ/ńe (my/mine), -a (your/yours), -oba (his), -ori (our), -ono/-ai (your/yours), -ano/-ota (her).[4]

Interrogative pronouns

Interrogative pronouns: abura (who), bi or yara (what), tja (where).[4]

Verbal suffixes

See the paragraph above on personal pronouns.

Imperative form

The information about the imperative form is also somewhat unclear, but as one sees in the following example, it has been observed, that there is surely a difference between an imperative in a singular form and in the plural (a suffix -ano is gained in the plural): ŭṅo! (you go!) uṅano! (pl. you go!)[4][5].

Conjugation of the verb "to have"

| Pronoun [eng.] | Nding | Translation |

|---|---|---|

| I | bāno/banŏ | "I have" |

| you | banŏē | "you have" |

| he | banŏē | "he has" |

| we | gari | "we have" |

| you (pl.) | andona | "you (pl.) have" |

| they | ano andona | "they have" |

Past tense

Exemplary conjugation of a phrase "to break a stick": koñi guri (I broke a stick), koño guri (you broke…), koñoba guri (he broke…), koñori guri (we broke..), koñata guri (you [pl.] broke…), koñata guri (they broke..)[5].

Adverbs

Adverbs: nĕnna (here), tegu (yesterday).[4]

(Pre- and post-)positions

Postpositions: ma/nā/nӑ (used for negation).[4][5]

Prepositions: ra („in“ in a sense, when someone is asking for a location of something), ba („to“), an („from“), nā („at/on“), tuko („outside“), tuka („at/on“ in a sense, when someone asks about location), djeta (“far from”), noṅgotjon (“close to”), tenyagan (“under”), ti/tiaritjo (“in the middle of”).[4]

References

- Nding at Ethnologue (25th ed., 2022)

- Atlas of the world's languages in danger. Christopher Moseley, Alexandre Nicolas, Unesco, Unesco. Intangible Cultural Heritage Section (3rd ed. entirely revised, enlarged and updated ed.). Paris: Unesco. 2010. ISBN 978-92-3-104095-5. OCLC 610522460.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Eberhard, David M.; Simons, Gary F.; Fenning, Charles D. (2020). Ethnoloɠue: Languages in Africa and Europe (23rd ed.). Dallas: SIL International Publications. p. 279. ISBN 978-1-55671-458-0.

- Meinhof, Carl (1965) [1910-1919]. "Eliri". Zeitschrift für Kolonialsprachen. 7/9: 36–50.

- Seligmann, Brenda Z. (1965) [1910-1919]. "Note on the Language of the Nubas of Southern Kordofan". Zeitschrift für Kolonialsprachen. 1/2: 167–188.