Nazran uprising

The Nazran uprising (Russian: Назрановское восстание, romanized: Nazranovskoe vosstanie) was an uprising of the Ingush people against Russian authorities that took place in 1858.

| Nazran uprising | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Caucasian War | |||||||

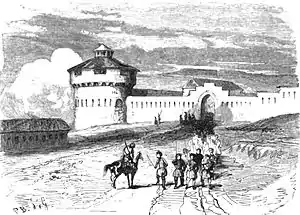

Drawing of Nazran Fortress in 1859. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

Limited support: | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Unknown |

First invasion: | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Unknown |

Unknown

| ||||||

In 1858, Russian administration began forcibly enlarging smaller settlements into larger ones, banning Ingush highlanders the rights to carry knives. On 23 May, the final impetus for the uprising became an attempt by the Bailiff of the Nazranian and Karabulak peoples to obtain necessary information about the number of residents in Nazranian Society which brought unrest among the Ingush.

Fearing an uprising, the bailiff requested military reinforcements to Nazran. On 24 May, Colonel Pavel Zotov arrived with Russian troops from Vladikavkaz Fortress. The rebels numbering about 5 thousand people attempted to storm the Nazran Fortress once they had learned about the capture of deputies they had sent to Zotov, but the storm was unsuccessful. The attackers were repulsed by artillery and rifle fire of Russian troops. The leaders of the uprising were executed, except Dzhogast Bekhoev, who managed to escape.

The Ingush sought the support of Imam Shamil, who decided to use this movement for his political plans to combat the Russian offensive on Dagestan. On June, He invaded Little Chechnya and soon arrived in Ingushetia where he was welcomed by the rebels. However, the division of Nazranians and weak support for Shamil became the reason for his failure. Shamil didn't have enough supplies and the Nazranians didn't provide him either. Shamil retreated back to Caucasian Imamate.

On August, Shamil with a force of 4000 tried once again to break through to the Area of Nazran, but in the Sunzha Valley Shamil's forces were immediately attacked by Russian forces led by Colonel Mishchenko and were completely destroyed leaving no choice for Shamil but to retreat with big casualties.

Names

The uprising is known under various names such as Nazran rebellion, Nazran outrage,[2] Nazran riot.[3] Sometimes the uprising was simply referred as the Nazran incident, or uprising of Ingush.[4][5] However, the uprising is most commonly known as Nazran uprising.[6][7]

Background

During the beginning of 19th century, Ingush formed small villages with several families in each village on the plains. This, however, didn't meet with Russian Empire's tsarist authorities' plans as they planned on forcibly merging small settlements into larger ones, with the requirements being that every village should have at least 300 households.[7] Forcible merging of small settlements into larger ones made it easier for Russian authorities to control and oversee the local populations.[8][9]

According to the reports of Russian officials, the cause of the uprising was the forcible merging of smaller settlements into larger ones and the organized census. Soviet Russian historian Nikolai Pokrovsky disagrees with this version, claiming the actual cause was due to the expropriation of Ingush lands, done in order to free up lands on top of which the future Cossack stanitsas could be established. The stanitsas essentially divided Ingushetia into two completely separate parts: mountainous and flat.[10] The additional cause of the uprising was possibly the ban on carrying knives.[11]

"The main reason for the Nazran uprising was the impossibility of having proper supervision of the inhabitants during scattered settlement in separate farms, and therefore I recognized it necessary to settle them in large auls in the places we had chosen [...] At the same time, completely independently of this, the Committee established in Vladikavkaz to analyze personal and land rights of the natives demanded from the Nazran deputies information on the population. Opponents of public order took advantage of the clash of these two circumstances and angered the people."

Storm of Nazran Fortress

On 23 May 1858, the final impetus for the uprising was an attempt by the bailiff of the Nazranian and Karabulak peoples to obtain necessary information about the number of residents in Nazranian Society in order to resolve the issue of land acquisition and merge of small villages into larger ones. Few Ingush agreed to move to Russia's appointed large settlements, however majority were against this, the foremen even demanding bailiff he wouldn't permit those who expressed a desire to move to large villages.[12] In the evening, Ingush gangs consisting of horsemen traveled around the surrounding villages and, with gun shots, called people to arms to the heights opposite of Nazran Fortress. In order to prevent a uprising, the bailiff requested Russian authorities to send military reinforcements to Nazran.[13]

On 24 May, Colonel Pavel Zotov arrived with Russian troops from Vladikavkaz Fortress.[13][14] Zotov ordered the local Nazranian foremen to calm the people, but they no longer controlled the situation.[14]

On 25 May, Ingush of Russian officer ranks appeared to Pavel Zotov whom Zotov wanted to send to the rebellious people in order to have in the disorderly crowd people who were influential and "should speak in his favor". The crowd not only didn't accept these officers but even threatened to kill them. By noon, a deputation of 6 people came to Zotov, including 4 main leaders of the uprising. The deputation stated that the Ingush people did not want to settle in large villages, that they didn't know the uprising's provokers and wouldn't extradite them.[13] Zotov demanded an end to the unrest[14] and kept 4 leaders of the movement as hostages.[13] The rebels numbering about 5 thousand people attempted to storm the Nazran Fortress once they had learned about the capture of deputies, but the storm was unsuccessful. The attackers were repulsed by artillery and rifle fire of Russian troops.[14]

The uprising left impact on the neighboring Ingush societies as there were raising movements as well. On May 28, the Khamkhins held a public meeting, invited the Fyappins and Dzherakh, but these latter did not attend the meeting. The purpose was to provide assistance to the Nazranians. At the same time, as one Russian report puts it, "a huge party of disobedient people stands not far from the village of Tsorins."[15]

The uprising of Ingush was led by the Chandyr Archakov, Magomet Mazurov and Dzhagostuko Bekhoev. Together with mullahs Bashir Ashiev (ethnic Kumyk[16]) and Urusbi Mugaev, they planned the uprising and took especially active part in writing up a letter to Imam Shamil on behalf of the entire Nazranian Society with a proposal to take an oath of allegiance to him and leave from Russian rule.[17] To their letter, Shamil replied with an appeal, calling them for arms to join his army.[14]

Imam Shamil's Support

The Ingush sought the support of Shamil, who decided to use this movement for his political plans to combat the Russian offensive on Dagestan. On 29 May, Naib Sabdulla Gekhinskiy sent seven messengers to the Galashians and Nazranians with announcement of Shamil's imminent arrival and offered to hand over the amanats.[18][lower-alpha 2] On June 1, the messengers returned back to Shamil with the amanats brought from these societies. Shamil instead sent the amanats back, promising support and providing them with an appeal calling on the Ingush people to a general uprising.[18] He carried out a general mobilization, gathering an army numbering 8000 (mostly Tavlins).[14] By taking advantage of the movement of the Nazranians and Galashians, Shamil invaded Little Chechnya.[18] In response to Shamil mobilizing troops, The Russian forces gathered two divisions, six battalions, fourteen companies, sixteen Cossack ten, twenty-two cavalry, foot and mountain guns. These Russian forces were located in strategically important points: in Assinovskaya, Achkhoy-Martan, in the Tarskaya Valley and in front of Vladikavkaz fortress.[14]

Shamil's appearance in Ingushetia was greeted with joy by the Ingush rebels. The Galashians recognized his power and handed over the amanats. Majority of Karabulak and Galashian elders defected to the side of Shamil. The division of Nazranians and weak support for Shamil was the reason for his failure. Shamil didn't have enough supplies and the Nazranians didn't provide him either. Thus, Shamil had to retreat. Moreover, on 9 June, one of Shamil's detachments under the command of his son Kazi-Magomet was defeated in a minor skirmish near the village of Achkhoy, losing 50 people.[18]

During Shamil’s retreat, part of the Nazranians, mainly from the Temirkhanov family, even pursued and crushed his rearguard.[20] Shamil moved to river Fortanga and occupied the villages of Alkun and Muzhichi in the Assa Gorge. From there Shamil tried to go to Vladikavkaz along the Akhki-Yurt gorge. On June 13, Shamil's forces camped in the upper reaches of the river Sunzha, the Russian forces on the other hand once again reinforced the troops with six hundred Alagir, Kurtat and the Ossetian militia and two hundred of the mountain Cossack regiment, which were moved by forced march to Vladikavkaz.[14]

Shamil, realizing that he would not be able to break through to the plane, gave the order to retreat and on June 15, the troops moved towards Meredzhi and Dattykh. While the Shamil's troops were retreating, the Russian troops simultaneously occupied the subject territories from the retreating Shamil's forces. After Shamil passed through Akkin and Shubut societies and crossed both currents of river Argun, he dissolved part of the army and retreated to the Imamate's capital, Vedeno.[16]

On August of 1858, Shamil together with a force of 4000 tried once again to break through to the Nazran area, but in the Sunzha valley Shamil's forces were immediately attacked by Russian forces led by Colonel Mishchenko and were completely destroyed leaving no choice for Shamil but to retreat. Whilst Shamil lost 370 of his men and 1700 different weapons, the Russians had only 16 men dead and 24 wounded. According to Shamil himself, he was called by Mussa Kundukhov, the commander of the Voeynno-Ossetinskiy Okrug, promising to act in cooperation.[16]

Aftermath

The Nazran uprising ended as a defeat for the rebels[16] which marked the conquest of Ingushetia into Russian Empire.[3][16] The leaders of the uprising: Chandyr Archakov, Magomed Mazurov, Dzhogast Bekhoev, mullahs Bashir Ashiev and Urusbi Mugaev were sentenced to death by hanging. Only Bekhoev managed to escape, the others were hanged on 25 June 1858. 32 people were sentenced to 1000 blows with gauntlets each, 30 to hard labor, five to indefinite work in mines, 25 to work in factories for 8 years.[16]

Although, the rebels were defeated, it may have saved them from more serious events. At that time, the Russian authorities were discussing the project to increase Russian population in the Caucasus while the local populations would be settled to the Don river. After the uprising, the leadership of Russia concluded:[16][2]

"[...] if only the offer to peaceful Nazranians to concentrate in large villages, on the plot of land they occupied, served as a pretext for an uprising, then the offer to the mountaineers, who have to express humility, to leave their homeland and go to the Don will serve as a pretext for a fierce war and, therefore, will lead to extermination, and not the obedience of the highlanders."

— Adjutant General Vasilchikov

Notes

- Consisted of Nazranians, Karabulaks and Galashians.[1]

- Amanat–hostage, given as security for a contract.[19]

References

- Arapov et al. 2007, pp. 137–138.

- Matiev & Muzhukhoeva 2013, p. 59.

- Genko 1930, p. 690.

- Anchabadze 2001.

- Shnirelman 2006, p. 185.

- Gritsenko 1971, p. 45.

- Dolgieva et al. 2013, p. 264.

- Anchabadze 2001, p. 47.

- Tsutsiev 1998, p. 175 (note 45).

- Pokrovsky 2000, p. 474.

- Istoriya narodov Severnogo Kavkaza 1988, p. 259.

- Skitsky 1972, p. 178.

- Skitsky 1972, p. 179.

- Dolgieva et al. 2013, p. 265.

- Skitsky 1972, p. 181.

- Dolgieva et al. 2013, p. 266.

- Skitsky 1972, p. 180.

- Skitsky 1972, p. 182.

- Bolshaya sovetskaya entsoklopediya 1926.

- Skitsky 1972, p. 183.

Bibliography

Russian sources

- Anchabadze, G. Z. (2001). Gelashvili, N. V. (ed.). Вайнахи [Vainakhs] (PDF) (in Russian). Tbilisi: Kavkazskiy dom. pp. 1–97.

- Arapov, D. Yu.; Babich, I. L.; Bobrovnikov, V. O.; Gakkaev, J.; Kazharov, V. Kh.; Krishtopa, A. E.; Solovyeva, L. T.; Sotavov, N. A.; Tsutsiev, A. A. (2007). Bobrovnikov, В. О.; Babich, I. L.; Redkollegiya serii "Okrainy Rossiyskoy imperii" (eds.). Северный Кавказ в составе Российской империи [North Caucasus as part of the Russian Empire]. Historia Rossica (in Russian). Moskva: Novoe literaturnoe obozrenie. pp. 1–460. ISBN 978-5867935290.

- Schmidt, O. Yu.; et al., eds. (1926). [Amanat]. Bolshaya sovetskaya entsoklopediya (in Russian). Vol. 2: Akonit - Anri (1st ed.). Moskva: Izd-vo Bolshaya sovetskaya entsoklopediya. col. 374 – via Wikisource.

- Dolgieva, M. B.; Kartoev, M. M.; Kodzoev, N. D.; Matiev, T. Kh. (2013). Kodzoev, N. D.; et al. (eds.). История Ингушетии [History of Ingushetia] (4th ed.). Rostov-Na-Donu: Yuzhnyy izdatelsky dom. pp. 1–600. ISBN 978-5-98864-056-1.

- Genko, A. N. (1930). "Из культурного прошлого ингушей" [From the cultural past of the Ingush] (PDF). Записки коллегии востоковедов при Азиатском музее [Notes of the College of Orientalists at the Asian Museum] (PDF) (in Russian). Vol. 5. Leningrad: Izd-vo Akademii nauk SSSR. pp. 681–761.

- Gritsenko, N. P. (1971). Классовая борьба крестьян в чечено-ингушетии на рубеже XIX-XX веков [The class struggle of peasants in Chechen-Ingushetia at the turn of the 19th-20th centuries] (in Russian). Grozny: Chech.-Ing. kn. izd-vo. pp. 1–108.

- Matiev, T. Kh.; Muzhukhoeva, E. D. (2013). Albogachieva, M. S.-G.; Martazanov, A. M.; Solovyeva, L. T. (eds.). Ингуши [The Ingush]. Narody I kultury (in Russian). Moskva: Nauka. pp. 58–69. ISBN 978-5-02-038042-4.

- Martirosian, G. K. (1933). История Ингушии: Материалы [History of Ingushiya: Materials] (in Russian). Ordzhonikidze: Serdalo. pp. 1–323.

- Narochnitsky, A. L.; et al., eds. (1988). История народов Северного Кавказа (конец XVIII в. — 1917 г.) [History of the peoples of the North Caucasus (late 18th century - 1917)] (in Russian). Moskva: Nauka. pp. 1–659. ISBN 5-02-009408-0.

- Pokrovsky, N. I. (2000) [1941]. Gadzhiev, V. G.; Pokrovsky, N. N. (eds.). Кавказские войны и имамат Шамиля [Caucasian Wars and Shamil's Imamate] (in Russian). Moskva: ROSSPEN. pp. 1–511.

- Shnirelman, V. A. (2006). Kalinin, I. (ed.). Быть Аланами: Интеллектуалы и политика на Северном Кавказе в XX веке [To be Alans: Intellectuals and Politics in the North Caucasus in the 20th Century] (in Russian). Moskva: Novoe literaturnoe obozrenie. pp. 1–348. ISBN 5-86793-406-3. ISSN 1813-6583.

- Skitsky, B. V. (1972). Tedtoev, A. A. (ed.). Очерки истории горских народов [Essays on the history of mountain peoples] (in Russian). Ordzhonikidze: In-t istorii, ekonomiki, yaz. i lit. pri Sovete Ministrov SOASSR. pp. 1–380.

- Tsutsiev, A. A. (1998). Осетино-ингушский конфликт (1992—...): его предыстория и факторы развития. Историко-социологический очерк [Ossetian-Ingush conflict (1992–...): its background and development factors. Historical and sociological essay] (in Russian). Moskva: ROSSPEN. pp. 1–200. ISBN 5-86004-178-0.

Further reading

- Baddeley, John F. (1908). The Russian Conquest of the Caucasus: with maps, plans, and illustrations. Harlow: Longsmans, Greens and Co. pp. 1–518.

- Skitsky, B. V. (1930). Назрановское возмущение 1858 г. (страница из истории ингушского народа) [Nazran indignation of 1858 (a page from the history of the Ingush people)] (in Russian). Vladikavkaz: Tipo-foto-tsink. Iz-va "Rastdzinnad". pp. 1–16.